|

To the average Canadian outside of Winnipeg in the summer of 1919, it must have seemed as if that city was at war. On 13 May the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council (WTLC) tallied the vote of its nearly 100 affiliated unions on whether to call city-wide action in sympathy with striking construction and metal workers. The result was 11,000 in favour and 500 opposed. Two days later a general strike of over 25,000 union and non-union workers began – paralyzing Winnipeg’s industry, transport, fire, police, postal service and communications. The city’s three daily papers, with a combined circulation of approximately 14,500, were forced to close on 16 May when union staff shut down the presses. Like a prairie wildfire, labour difficulties seemed to spread across the nation from the capital of Manitoba. The bitter and protracted dispute in Winnipeg, ending in arrests, demonstrations, violence, injuries and death, was to last 41 days, making it the longest general strike in Canadian history.

In over 130 Canadian cities served by daily newspapers, apprehension and fear became the dominant feelings of hundreds of thousands of readers, as the dispute in the prairie center seemed unsolvable and unstoppable. In gripping headlines, flaming editorials and cartoons, almost every major newspaper, including powerful American dailies, dramatically reported and editorialized Winnipeg’s strike as a Bolshevik-One Big Union [1] conspiracy to topple constituted authority. In Toronto, five of the six dailies accepted and exploited this theory. Shock followed by condemnation and a defiant call for strong action against the strikers was their collective response.

Only the Toronto Daily Star refused to accept this viewpoint. Instead, through news reports and editorials, the paper presented its readers with a different interpretation: that for the majority of the strikers in Winnipeg the real issues were essentially collective bargaining and higher wages. History has since proven that The Star’s version was considerably more credible than the idea of revolutionary plots, foreign agitators and “reds,” and more compatible with the actual events in Winnipeg between 15 May and 27 June. Why and how did The Star provide a more accurate version and interpretation? The answer lies in the convictions of the paper’s owner, Joseph Atkinson, and the investigative reporting of two veteran newsmen: Main Johnson and William Plewman.

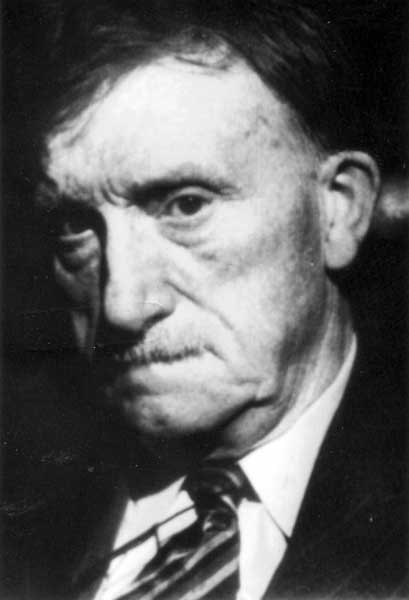

Editor Joseph Atkinson of The Toronto Daily Star, circa 1900.

Source: Toronto Star Archives

Toronto in 1919 witnessed Joseph Atkinson and The Toronto Star engaged in a fierce circulation battle with no less than five other daily newspapers, in particular The Evening Telegram, but also The Globe, World, Mail and Empire, and News. With the exception of The Globe, the other four dailies traditionally supported Conservative governments. However in 1919, even the staunchly Liberal Globe was committed to the Union coalition of Sir Robert Borden, so the Prime Minister had virtually no opposition in Toronto from powerful newspapermen like John “Black Jack” Robinson of The Telegram, Senator Robert Jaffray of The Globe, William Douglas of The Mail and Empire, and William “Bug Eyes” Maclean of The World. Equally important, these proprietors and editors were generally not sympathetic to the problems of the working class, and were strongly influenced in 1919 by the “red scare” – the fear of an international communist conspiracy. [2] It was thus in an atmosphere of paranoia that these papers, their owners, publishers and editors viewed the strike in Winnipeg.

When Joseph Atkinson took over editorship of the Evening Star in 1899, it was known as a “paper for the people.” Within a year Atkinson had changed the name to the Toronto Daily Star and began to instil a crusading spirit. Gradually he transformed the paper into an advocate for social reform legislation focusing on minority rights, public ownership of utilities, and the right of labour to organize and strike. [3] With the help of prominent trade unionists like Tom Banton, James Simpson and Fred Bancroft, The Star eventually acquired an expertise on labour issues. In fact, no other daily in Toronto could match its labour columns. Atkinson’s decision to make The Star the champion of the working class was one of the main factors in increasing the paper’s circulation. In 1899 it was mired at 7,000. In 1910 it had increased to 9,500. However, by May 1919 it was up to 88,000, and after the strike coverage, the figure was up to 93,000.

When labour disruptions threatened post World War I Canada, Atkinson could clarify and explain the motives behind these actions, leaving less informed papers to respond with confusion, alarm and hostility. While other newspapers promoted the theory that an attempt at Soviet style revolution was behind the strike in Winnipeg, Atkinson assigned another cause. He felt that the use of a general strike was an example of the rising scale of working class militancy, and that the strikers were employing this tactic as a last resort to gain long delayed economic concessions. So he chose to not accept an attempt at overturning constituted authority as the cause of the strike. Why? First, his knowledge of labour issues. Second, his genuine sympathy for the workers. Third, his opposition to Borden and an opportunity to embarrass him if the strike was mishandled. Fourth, his business instincts. Atkinson always kept an eye on The Star’s bank balance. He knew that his core readers were from the working class, so to provide exceptional strike coverage was imperative to maintain revenue and hopefully increase circulation. Finally, the reports from Winnipeg from two of The Star’s best reporters confirmed his own thinking about the dispute.

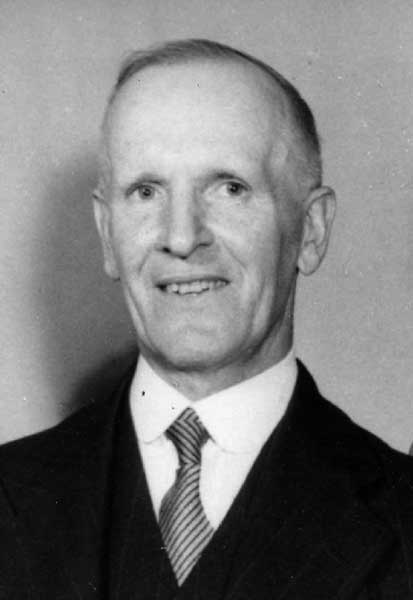

Prior to the general strike, relations between Winnipeg’s daily newspapers—The Manitoba Free Press, The Winnipeg Tribune and The Winnipeg Telegram—and organized labour had been less than cordial. In 1918, The Free Press, owned by Clifford Sifton, managed by Edward Macklin “The Chief,” and edited by John Dafoe, had been officially barred from WTLC meetings because of alleged misrepresentation of labour speeches. In April 1919, The Tribune, co-owned by Robert L. Richardson and John J. Moncrieff, and edited by Moncrieff, had been blacklisted by several Winnipeg unions for the paper’s editorial comments about the March Western Labour Conference in Calgary. The Telegram, whose ownership and control was linked to former Winnipeg mayor, Sanford Evans as well as prominent Conservative politicians, Sir Rodmond Roblin and Robert Rogers, was edited and managed by Knox Magee. The paper was nicknamed the “Yellowgram” by local labour because of its anti-union views. Magee was personally attacked during the walkout by the strikers’ paper, The Western Labor News. On 2 June it contemptuously declared, “Such filth as this (Magee’s writing) comes only from a depraved mind. Fare thee well, Knox Magee, we shall not honor you again with references to your disgustingly depraved news rag.” [4]

John W. Dafoe, Editor of the Manitoba Free Press, no date.

Source: University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections, Tribune Collection, Personalities Files.

“What did you miss during the strike? Streetcar service? Restaurants? Telephones? Mail? Newspapers?” On 24 May The Tribune asked this question to hundreds of Winnipeggers. According to the paper, “In nine out of ten cases the answer was, ‘Newspapers’.” [5] The closure of Winnipeg’s three daily papers began on 16 May with the walkout by all stereotypers and Webb pressmen. Four days later, the largest daily, The Free Press, was able to resume limited publication. The Tribune and The Telegram reappeared on 24 May. By 29 May all three were printing eight pagers although at first without advertising, and on 3 June regular editions finally hit the streets.

Meanwhile, both sides in the strike published their own papers. The Central Strike Committee turned the WTLC’s paper, The Western Labor News, into a daily special strike bulletin beginning on 17 May. Organized opposition to The News quickly appeared two days later in The Citizen, a daily paper controlled by a volunteer organization of business and professional men called the Citizen’s Committee of 1000. Until the end of the strike The News and The Citizen vilified each other with every issue.

As the Free Press, Tribune and Telegram returned to regular publication, they too joined the attack on The News. An example of their willingness to support the Citizen’s Committee was the repeated running of large anti-strike notices from this organization. However, the decision to run these notices was not surprising given the adversarial history between The News and the three daily papers, especially after the Central Strike Committee had approved their closure. Four days into the strike, William Ivens, the editor of The News, had justified silencing all three of Winnipeg’s daily papers.

A year ago we issued a strike bulletin to call their bluff and correct their misstatements. They soon forgot, and again told half-truths or suppressed the real facts … surely it is justice at this time to muzzle for a few days the enemies of freedom and truth … we do not think they like it all, but for nearly five years they have been howling off their heads to suppress papers that told the truth. [6]

William Ivens, editor of The Western Labor News, no date, carried on a running editorial battle with the Free Press, the Winnipeg Tribune, and the Winnipeg Telegram, calling their campaigns against the Strike “vile and pernicious propaganda.”

Source: Archives of Manitoba, N10452.

Ivens’ claim that “we do not think they like it all” was an understatement. When The Free Press resumed publication on 24 May, the paper complained it had been “the victim of a revolutionary plot and had been suppressed by orders from the dictatorship of the proletariat.” [7] The Tribune’s first editorial asserted that behind the strike was a small group of Bolshevik agitators “irresponsible, lawless, anarchistic agitators.” [8]

Two days after The Telegram was again publishing, its front-page, two column editorial criticized the strike as a Bolshevik conspiracy involving “Red Socialists and Anarchists” and a “hostile alien element.” [9] The battle lines were now drawn. What emerged was a relentless and bitter “war of words” fought on the papers’ front pages and in editorials, as well as through anti-Bolshevist advertisements provided by the Citizen’s Committee.

This press feud was characterized by The Citizen, Free Press, Tribune and Telegram trading stinging editorials, malicious innuendo and threats with The News. Meanwhile The News labelled the campaign against it as “vile and pernicious propaganda” from “the purchased prostitute press,” “the plutocrat owned press” and “the mendacious purchased press.” For the citizens of Winnipeg, the alarming rhetoric between the two sides must have appeared out of control. Soon however this rhetoric was also out of the city and appearing in newspapers throughout the dominion.

During the strike Canadians received information on events from four sources: Winnipeg based “stringers,” Canadian Press (CP) news service, the American press, and Canadian reporters sent to Winnipeg. For the few Canadian reporters, there were many obstacles to not only obtaining the facts but also conveying them back to their papers. The Winnipeg Tribune effectively summarized these difficulties on 2 June:

When newspapers and press associations sent their ‘war correspondents’ to Winnipeg to cover the strike, the laconic instruction was, ‘Ship the news out quickly. Beat the other fellow.’ But Winnipeg proved original and peculiar. They found a Citizen’s Committee about as loud as an oyster in divulging news. A union card was necessary for grasping a few facts from the labor leaders. The provincial end of the government seemed as happy to receive newspapermen as Lenin would be as seeing Kerensky hang his hat on the Lenin peg in the Hall of the Commissariats. They found rumor factories on every corner … When they found news it was another matter putting it on the wire. The telegraphers went out the day they arrived. [10]

Almost all commercial and brokerage telegraph service abruptly ceased on 17 May. As well, the Central Strike Committee immediately imposed censorship on outgoing news. As a result some outside press representatives journeyed to other Canadian cities such as Brandon, Regina and Fort William, while others crossed the border into North Dakota and Minnesota to file reports back into Canada via American wire services. Until regular wire service was re-established in Winnipeg on 12 June, dispatching complete and uncensored news stories was indeed challenging.

Stringers were freelance journalists or special correspondents used to provide news and views of events in cities to papers without its own reporters on location. Payment was based on the amount written and as a result there was a temptation for quantity to often replace quality and exaggeration to pass for fact. [11] During the Winnipeg strike two Winnipeg stringers, Garnet C. Porter and John J. Conklin, supplied information and views to outside papers. Porter was employed by The Toronto Evening Telegram and The Montreal Star, while Conklin worked briefly for The Toronto Star and then for The Montreal Star and Halifax Morning Chronicle.

Porter, nicknamed the Colonel, was one of the West’s most colourful newsmen. Born in the United States, he came to Canada at age thirty-four, leaving behind an adventure-filled past as a legal counsel, Kentucky outlaw and feudist, soldier of fortune and Yukon prospector. It was claimed that he kept a loaded pistol in his desk. He eventually settled in Winnipeg working for eleven years as the editor-in-chief of The Winnipeg Telegram.

When Porter left The Telegram in 1917, he established his own press service, Porter’s International Press News Bureau. He located this one-man version of CP in the C.P.R.’s luxurious Royal Alexandra Hotel. During the dispute his reports to The Montreal Star and Toronto Evening Telegram were often sensational in tone and slanted against the strikers. While he complimented the Citizen’s Committee of 1000 as a “marvelous organization” he described the actions of the strikers as a “labour siege.” When marches by pro-strike ex-servicemen occurred, Porter labelled the demonstrations the “radicals’ parades,” whereas counter demonstrations by “Loyalist” veterans were the work of the “sane returned men of Winnipeg.” [12] On 9 June, the Montreal daily ran one of Porter’s story which included his announcement that Secret Service men of Canada and the United States are planning to spring a trap on a known number of I.W.W. (International Workers of the World) and other red agitators who have crossed the boundary into Canada to help put over the program of Soviet-Labour rule. [13] From his reports it was clear that he opposed the strike, but what was not popularly known was that Porter disliked J. S. Woodsworth, John Queen, George Armstrong and the rest of the strike leaders. [14]

The second stringer was John J. Conklin. He was born in Forest, Ontario and came to Winnipeg at the age of thirteen. An editor of the University of Manitoba paper, Conklin joined The Manitoba Free Press in 1886 and was to remain with the paper for 51 years, holding more positions than any other employee. In 1919 his department was drama and music; however, he was also a stringer for a number of Canadian, American and British papers. [15] When the strike began, John Bone, the managing editor of The Toronto Star, contacted Conklin to string for a few days until Main Johnson arrived. Conklin was told to meet Johnson on his arrival and help him gather and send news to Toronto. From 20-22 May, Conklin wrote twelve reports to The Toronto Star and collaborated with Johnson on two others. Conklin’s dispatches for The Toronto Star were definitely not anti-strike. Yet, when he wrote for The Montreal Star, a daily openly opposed to the strike, Conklin’s stories became more critical of the walkout and those leading it. [16] On 10 June, in The Halifax Morning Chronicle he called strikers “union labor of the worst type.” [17] Why his view changed is not clear. Perhaps he believed the theory of the strike as a revolutionary conspiracy. Maybe he felt Winnipeg was being torn apart and he blamed the strikers. Or possibly his reports to The Toronto Star were not critical of the strike because he knew the paper’s pro-labour stand.

Industrial Bureau, Headquarters of the “Citizens Committee of One Thousand” during the Winnipeg General Strike, June 1919.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Foote Collection 1688, N2754.

Among the wire service men who left their keys on 17 May, were the six unionized workers at the CP headquarters in the Manitoba Free Press building on Carlton Street. At the same time the Central Strike Committee notified CP management that news reports could leave the city if first subject to striker censorship; however, this offer was immediately rejected. [18] By 21 May CP had creatively solved its dilemma of providing uncensored wire copy. With the co-operation of the American press a private wire was cut into St. Paul, Minnesota where American operators picked up the transmissions from CP’s chief telegraph operator, Frank “Never Break” Turner. Turner earned this nickname during the strike because he worked day and night both sending and receiving messages. [19] Despite Turner’s remarkable exploits; it was doubtful that many objective reports about the strike left Winnipeg. The reason was that with a small staff CP did little independent news gathering. Instead, the fledgling service, begun in 1917, relied heavily on duplicate copies of news stories provided by Winnipeg’s three dailies—sources that were hostile to the strike and especially to its leaders. The implication was national in scope because almost every major daily in Canada used CP dispatches from the Winnipeg bureau on the strike. Client papers edited the CP wired copy, assigned a headline, and then usually ran the story on the front or second page. However, not all readers were discerning enough to know how the report originated, was filtered and then shaped into a final story. Usually CP reports were not by-lined but J. F. B. Livesay, CP’s Winnipeg bureau manager, made an exception on 23 May in his dispatch which appeared in The Toronto Globe under the headline “To Oust Reds From Unions.”

The question of permanent industrial peace in Winnipeg, evolving from the present general strike of local Labor unions which developed phases nation-wide in scope, rested to-night on the future status of the radical alien enemy. Leading citizens of Winnipeg, including Mayor Charles Gray and Members of the Common Council (City Hall) to-day joined with Provincial and Federal authorities in informing union Labor workers of this city that either the alien extremists in the union ranks must be ousted or every force of law and order will be concentrated to rid the Dominion of this element. [20]

Within a week of the strike’s outbreak the American press gained a distinct advantage over its Canadian counterpart reporting news about the strike. By 20 May both Associated Press (AP) and United Press (UP) were carrying news reports over a leased wire. AP and UP could do this because they brought their own operators and so were not technically strike-breakers. As well, American reporters arrived as early as 17 May from Duluth, Minneapolis and St. Paul. [21] A week later a party of ten descended on Winnipeg from New York and Chicago. [22] As the strike lengthened, it also attracted representatives from large American magazines such as Leslie’s Weekly and Colliers. On 29 May ‘moving pictures’ were taken of a veterans’ march on the provincial Parliament Buildings, and on 21 June Leslie’s Weekly featured a photo story by its internationally famed photographer, James Hare. His story was titled ‘Bolshevism in Canada.’ [23]

For the strikers, the reaction by the American press about the walkout must have been demoralizing. Four days after it began The New York Times headlined an editorial, “Leninism in Winnipeg”, declaring events as a “red plan.” [24] On 29 May, the influential Chicago Tribune placed a very clever cartoon by John McCutcheon on its front page. Captioned “Winnipeg Labor Ought To Take A Look Around First,” the illustration depicted a foreign demagogue (Dr. Agitator) offering an unsuspecting workingman (Winnipeg labour) the cure to all his ills. In the background a poisoned Russian worker groaned “That’s what he gave me.” [25] As proof that Canadians could be affected by anti-strike American opinion, this particular cartoon ran four days later on the front page of The Toronto Globe.

Many of the reports and editorial opinions of the Winnipeg General Strike by American papers fanned the hysteria of the “Red Scare” in the United States. Winnipeg city officials were even forced to deny early American reports that the city was on the brink of anarchy and that a “soviet” style government instituted. At one point union strike officials informed AP of their embarrassment of “fake stories of Soviet government” filed by “irresponsible correspondents.” [26] Equally significant is that accounts like these were used freely by Canadian papers and ultimately influenced their readers. American press reports and editorials even found their way back to Winnipeg appearing several times in May and June in The Free Press and The Citizen.

Almost every daily newspaper in Canada relied on stringers, CP and American press sources to provide news and views on the Winnipeg General Strike. Only two papers, The Toronto Star and The Toronto Evening Telegram, actually sent their own reporters to cover the strike first hand. It is likely that the great majority of dailies did not send staff to Winnipeg due to the cost and because they could rely on CP dispatches or American press sources. The reason The Telegram and The Star released reporters to Winnipeg, was that the two were the main evening papers and their rivalry for readers was intense. Providing complete coverage of the strike was another round in their ongoing fight for circulation. However, The Star had a second reason. It was a paper for the labouring class and so Atkinson wanted comprehensive coverage of a general strike. The Telegram sent Mary Dawson Snider. Nicknamed “Happiness”, she was the wife of Telegram editor, Jerry Snider. She arrived in Winnipeg in the first week of the dispute and sent stories until 10 June. Her reports, datelined Thief River Falls, Minnesota, suggested the Bolshevik nature of the strike and demonstrated a sympathy for the Citizen’s Committee. [27] The Star assigned two seasoned reporters to Winnipeg—Main Johnson and William Plewman.

William Main Johnson of The Toronto Daily Star, 1926.

Source: Toronto Public Library, Main Johnson Collection.

William Main Johnson was born in Hamilton, Ontario on 27 November 1887. At seven, he wrote his own weekly paper, which he circulated and sold among his friends. He obtained a regular summer job with The Star while attending University of Toronto. Upon graduation in 1910, with honours in history and English, Johnson joined The Star as a full-time cub reporter. However, in 1913 he became Newton Rowell’s principal private secretary when Rowell was successively leader of the Ontario Liberal opposition, president of the wartime Privy Council in Borden’s Union government, and member of the Imperial War Cabinet in London, England. In late 1918, the urbane, imaginative and well-traveled Johnson returned to The Star where he remained until 1946. [28] Upon his return in 1918, he was first assigned as the paper’s parliamentary reporter in Ottawa. However, Johnson soon developed into a special correspondent, travelling across Canada and covering outstanding events of interest to Star readers.

In April 1919, he was directed by Atkinson to accompany and report on the daily sittings of the eight-man commission headed by Chief Justice Thomas Mathers. This commission was investigating the state of industrial relations in Canada. The hearings in Winnipeg held between 10 and 13 May narrowly missed the outbreak of the strike. Ironically, during the hearings, on 12 May, Johnson had warned Star readers that a general strike in Winnipeg was imminent. One week later, on orders from The Star’s managing editor, John Bone, Johnson left the Mathers Commission in Sudbury and quickly returned by train to Winnipeg. At noon on 18 May, he arrived in Winnipeg, checked in to the Royal Alexandra Hotel across from the CPR station and soon met with John J. Conklin.

Atkinson had chosen Johnson not only because of his knowledge of labour relations, but also because of his familiarity with both William Ivens, the editor of the strikers’ paper, whom Johnson had met at the Mathers hearings earlier in the week, as well as federal government officials including Senator Gideon Robertson, the Minister of Labour, and Arthur Meighen, the Minister of Justice. Robertson was in Winnipeg to deal with the walkout of the postal workers who were federal employees, and Meighen was there to assess what action should be taken to end the strike as soon as possible. As well, Johnson was no stranger to Winnipeg or the prairies. From June to August 1915 he had accompanied Rowell on his Western tour, and in August 1917, Johnson had been Rowell’s observer at the Western Liberal Convention in Winnipeg. However, this time his visit to Winnipeg was as a journalist. After being briefed by The Star’s stringer, John Conklin, Johnson began covering the strike. The next day he filed his first of eleven stories to Toronto. In doing so, he soon encountered unusual if not unique news gathering and communication obstacles.

In trying to file his first dispatches from Winnipeg, Johnson learned that all of his reports were subject to the approval of a strikers’ censorship board. However, the head of this committee, William Ivens, offered him a concession. “I think I can arrange for you,” Ivens stated, “to wire 600 words daily to your paper, under your signature, but with my o.k. provided that the copy is passed by the strike committee and provided that you wire it to The New York Call, a labor paper in Butte, Montana, and probably a labor paper in Toronto too.” [29]

Johnson refused Ivens’ proposal and instead boarded the CPR’s “Soo Line” Express, 145 miles south to Thief River Falls, Minnesota where he wired his dispatch to The Star. All of Johnson’s subsequent reports were sent this way, either from Thief River Falls or from Grand Forks, North Dakota. Johnson’s maneuver was extremely important for The Star because it received first hand and uncensored stories on the strike from a veteran newsman, and thus did not have to rely on potentially biased pro or anti-strike sources. In fact, in just two days—19 and 20 May—The Star informed its readers that it provided them with over 9,000 words on the strike. [30]

During his eight days, covering the strike Johnson interviewed labour columnist and Manitoba MLA Fred Dixon twice as well as William Ivens, Mayor Charles Gray and Senator Gideon Robertson. Reaction from the Citizen’s Committee was impossible to obtain because members of this organization preferred to remain anonymous. However, he was able to interview one member of this group—a volunteer on the fire brigade who was a young lawyer and a former friend of Johnson’s from the University of Toronto.

From these interviews, collaboration with Conklin, previous knowledge of labour issues, and investigative reporting of strike developments, Johnson correctly concluded that the strike was not a Bolshevik-OBU conspiracy to take over government authority. Rather, as he wrote in The Star on 26 May, “a very large number of trade unionists, probably the vast majority struck on the simple and specific issue of collective bargaining, which they thought was being assailed in such a challenging way that there was no recourse but to clear the issue once and for all.” He was also aware that the work stoppage was being used by a minority of the strikers to obtain “an industrial republic within the political state,” and this action was motivated by the “rising gospel among workingmen (for the) doctrine of production for use.” He went on to explain how the strike was a challenge to the vested interests of “… that class in the community which up to the present has owned and controlled industry privately and has made profits from it.” [31] After filing this last dispatch, Johnson was contacted by The Star and reassigned to cover the June American Federation of Labor Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Meanwhile, Atkinson still had another reporter, William Plewman, to continue event coverage in Winnipeg.

William Plewman, cira 1940. Plewman reported on the Winnipeg General Strike for The Toronto Daily Star.

Source: George Plewman

William Rothwell Plewman was by 1919 a 16-year veteran of The Star. His career would continue with the paper until he retired in 1955. He was born in Bristol, England on 3 August 1880 and came to Canada when he was eight. At 13, he left Dufferin public school in Toronto and worked as a messenger boy and proofreader at the Methodist Bookroom. For a time Plewman thought of becoming a lawyer and spent four years in a law office. He then worked for the Maclean Publishing Company. At 19, he became a reporter on The Toronto News, and four years later, he joined The Star. From 1903 to 1912, he was the paper’s telegraph editor. He left the paper briefly for two years but returned just before the outbreak of World War I in August 1914. During World War I Plewman became famous for his regular Star column “The War Reviewed.” After the war, he wrote My Diary of The Great War (1918) and contributed to two other books on Canada’s military involvement in the struggle in Europe. In 1916 while working for The Star he successfully entered local politics as a city alderman for Ward Five. He was to win this ward again from 1918 to 1920 and in 1922. Plewman was a quiet man of medium build who always wore a Hoover collar and rimless spectacles. One of the few Orangemen on The Star, he was deeply religious and, unlike many of his contemporaries, he neither smoked nor drank. [32] Like Joseph Atkinson, Plewman believed in the public ownership of utilities, and eventually wrote a lengthy and sympathetic history of Sir Adam Beck and Ontario Hydro.

When the strike erupted on 15 May Plewman was in Toronto fulfilling his dual obligations as a full time Star reporter and a city official. As events developed in Winnipeg, Atkinson via John Bone, directed Plewman to join Main Johnson. Richard Plewman, William’s son, described his father’s sudden departure. “I remember my mother, all that she put together was a pair of shoes, one pair of underwear, that was all because he was only going to go out there and be back tomorrow.” [33] At 7:00 pm Tuesday, 20 May, William Plewman hurriedly boarded the train and was in Winnipeg two days later. His brother, Charles, who was then boys’ secretary at the downtown YMCA on Vaughan Street, recalled William’s arrival.

… all of a sudden a tap came on my door and the first thing I knew here was my brother, unannounced. My brother himself was a humanitarian … A great believer in the supreme worth of human personality. He was a man of pretty strong principles. I would say somewhat of a rugged individualist in his thinking. He was a very deeply religious man. He came to Winnipeg a great believer in trade unionism. [34]

On 22 May, William Plewman arrived in Winnipeg aboard the CPR Express. As his train crossed over the Louise Bridge and entered Point Douglas, he peered out his window for signs of the disturbance which had gripped the city for a week. Instead of scenes of disorder he spied the “good old Union Jack” flying high over the concrete flour mills of the Ogilvie Milling Company. [35] A few minutes later he walked the short distance from the train station to the red-bricked, seven-story, “Royal Alex”—the CPR hotel at Main and Higgins that was frequented by federal government officials. He registered unaware that his hotel room was to become home for the next five weeks.

From 22 May until 27 June Plewman sent The Star more than 55 reports totalling over 100,000 words. Of these stories 33 appeared on The Star’s front pages. Like Johnson, he had to wire these dispatches from Minnesota; at least until full telegraph service was restored in Winnipeg. Richard Plewman recalled a humorous anecdote related to his father’s news gathering when he was forced to use unconventional travel. “… Then he got ‘Old Dobbin’ which is a horse … So he got this old plough horse and dad had never been on a horse in his life … he was not a farm boy in any shape, so he took the horse back to wherever he was staying and they tied it up and he put on the outside ‘Union’ to protect the horse.” [36]

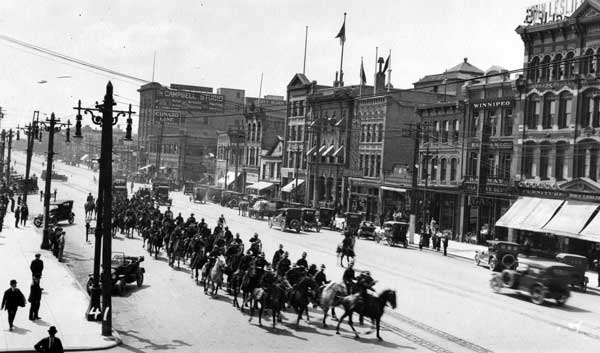

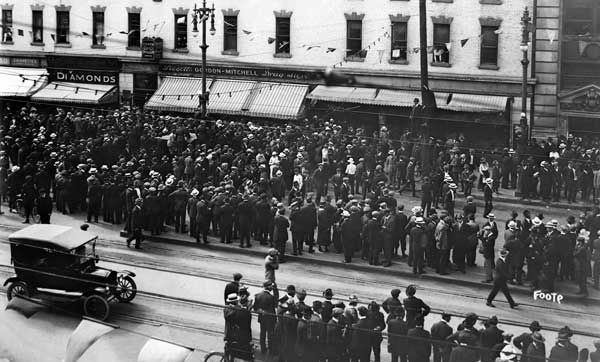

Plewman’s “beat” included City Hall across from Market Square on Main Street, the nearby Victoria Park, the Industrial Bureau further south on Main at Water Avenue, the Labor Temple on James Avenue and the Provincial Legislature on Kennedy Street. From his hotel room on the sixth floor he had an unobstructed view of cars of the Citizen’s Committee “scurrying down Main and Portage … 25 large flags tugging at their poles … the noise of newsies floating up to me.” [37] From the same vantage point on June 12 he watched “the cavalry exercising on Broadway … near the Fort Garry Hotel.” [38] As the strike persisted he visited two North end public schools, Gray and Aberdeen, with large numbers of immigrant students, and attended the services of the Labor Church in the Columbia Theatre. When the walkout entered its final two weeks he joined the throngs of returned soldiers at meetings and demonstrations, and was in the crowds in the 10 June fracas on Main Street involving “the specials” as well as the 21 June riot of “Blood Saturday.”

Mounted Police gather along Main Street during the strike, June 1919.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Foote Collection 1699, N2761.

Plewman obtained interviews with key figures in the strike including Senator Gideon Robertson, Abraham Heaps, Bob Russell and William Ivens. On 17 June, following the “midnight arrests” of eight prominent strike leaders, he interviewed J. S. Woodsworth in the Labor Temple on the day he was preparing to take over editorship of The News from the arrested Ivens. On 21 June, 45 minutes before the violence erupted on Main and Portage, Plewman secured an interview with Gideon Robertson and the spokesmen for the committee of striking veterans. For the employers’ side he met with James Carruthers, manager of Crescent Creamery, Alfred Ryley, manager of the Canada Bread Company, and Peter McIntyre, Winnipeg’s Postmaster. To obtain union views he talked with Lawrence Pickup (Postal Clerks), Ash Kennedy (Locomotive Engineers), Doris Meakin (Telephone Operators), A. J. McAndrew (CPR Maintenance Employees), and Herbert Lewis (Editor, The Ontario Labor News). Like his colleague Johnson, Plewman was unable to obtain interviews with members of the Citizen’s Committee of 1000.

In his first report to The Star on 23 May Plewman admitted that “the strikers have gone pretty far and they have made some mistakes, but they have not perpetrated Bolshevism.” [39] Like Main Johnson, Plewman reported that a small proportion of the strikers wanted to use the walkout as a springboard to a new industrial order. He quoted the radical social gospeler, the Rev. A. E. Smith, as describing this new system as one based “for use and not for profit, co-operative instead of competition.” [40] Men like Smith, Ivens and Woodsworth, Plewman observed, argued “that it is wrong that workers should have to go cap in hand to employers asking for the right to live and then getting at best only a bare subsistence when the country has stupendous resources.” [41] Plewman also believed that the majority of those who joined the strike did so because Winnipeg employers refused to recognize legitimate labour grievances. In a 27 May story he explained what he discovered:

Just what did happen in Winnipeg? As nearly as the writer can determine, this in brief is what happened. Three weeks ago the Metal Trades workers in contract shops went on strike to enforce collective bargaining, as they have it on the railways. The building trades also struck to enforce the same principle. Twelve days ago, the Trades and Labor Council, which within a year has unionized all the clerks, waiters, food makers and distributors, and movie employees, called a general sympathetic strike to assist the fight for collective bargaining. [42]

When 2000 returned soldiers marched to the Provincial buildings on 31 May and occupied the legislative chamber, Plewman reported that the veterans’ leader, Jack Moore, a “neutral,” former sergeant in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and member of Premier Norris’ Alien Investigation Board, emphasized that if collective bargaining were granted, the strike would be settled at once. Plewman quoted Moore. “The Citizen’s Committee has been talking about English and Scotch anarchists, and they’ve got to be stopped, and you can do it Mr. Premier … All we want is living conditions. Some of our comrades are working 74 hours a week for $55 a month … We want collective bargaining as they have it on the railways.” [43] During this same encounter between Norris and the returned veterans, Plewman reported a dramatic incident that showed the danger to newsmen who were perceived by some ex-servicemen as anti-strike. “One man in the press gallery wore a Union Jack (to many an anti-strike symbol) on his coat. ‘Take it off.’ ‘Take it off,’ cried the crowd. Finally one supposedly returned man jumped from the public gallery into the press gallery, 5 feet down and tussled with the flag wearer amid a hurricane of approval.” [44] In the days following the arrests of the strike leaders, Plewman was primarily interested in the reactions of the strikers to the government’s move. His account of “Bloody Saturday” was essentially factual though he did report the apparent indecision by authorities to call out the troops. In his final report to The Star Plewman once again cast doubt on the Soviet conspiracy theory. “Needless to say, if evidence of this sort can be brought out Canada is in for a genuine sensation.” [45]

Front page of the Toronto Daily Star, 23 May 1919 with articles by Johnson and Plewman

Source: Toronto Star Archives

From 15 May to 25 June The Evening Telegram, Globe, Mail and Empire, Times, and News together printed over 70 editorials, a dozen cartoons, and numerous editorial snippets (short notes, often satirical or humorous) about the Winnipeg General Strike. Their persistent editorial theme was that the trouble in Winnipeg was a terrifying manifestation of Bolshevism. For example on 23 May under the title “Need for Sobre Thought,” The Toronto News commented “Winnipeg is in the hands of the IWW’s and Bolsehvists who are bent upon prostituting organized labor to their own aggrandisement, upon overthrowing the established order of civilization and upon creating a proletariat dictatorship which would be as tyrannical as any autocracy ever seen.” [46] On 27 May The World stated its position quite clearly about Bolshevism and the OBU. In an editorial “Still More Threatening” it announced “Government representatives in Winnipeg have accepted the view which The World has all along taken that the strike has been fomented by the Bolshevistic or ‘One Big Union’ element in the West.” [47] On 3 June The Globe’s lead editorial was “Banish The Bolshie.” [48] After the 17 June arrests of the Strike leaders The Telegram’s editorial was “Rounding Up The Gang.” In it the comment was “The ringleaders and inciters of anarchy are being rounded up … There must be no stopping until the IWW agitators, Bolshevists and other friends of the enemy in the West cleaned out. Our cities in Western Canada must not be little Warsaws or Pragues, but orderly centres occupied by loyal citizens of the British dominion. The Government must not stop halfway …” [49] Shorter editorial comment in the form of snippets also suggested the Bolshevik connection. The Telegram 17 May: “Winnipeg now seems to be in process of being put on the map as the ‘Petrograd’ of Canada.” The Mail and Empire 23 May: “Some slight progress has been made in changing its name to Winnipegsky.” The Globe 11 June: “Winnipeg’s pegging holes in the gas-bag of revolution.” The Mail and Empire 14 June: “Everyone is agree that the country ought to be purged of alien agitators. Then when is the purging to begin?”

The news reports of these same papers also emphasized that Bolshevism and the OBU were the cause of the strike. On 19 May The Times, via Arthur Ford of its Ottawa bureau, reported “There is not the slightest doubt that there is a large ‘Red’ element in Winnipeg, who have been planning for months for a revolution in the west and are prepared to seize upon the present disturbance, if at all possible, to establish a soviet in Winnipeg and put into force the Bolsheviki principles.” [50] The Mail and Empire reported on 2 June, that many people, including Gideon Robertson, thought that the OBU was the underlying cause of the strike. “Hon. Gideon Robertson, Dominion Minister of Labor, in a statement made to the press before leaving for Ottawa … said that the promoters of the general strike in Winnipeg ‘now sit in the ashes of their own folly,’ that ‘sympathetic strikes must always fail,’ and that the Winnipeg strike is ‘the first rehearsal of the play written at Calgary.’” [51]

Crowd at Victoria Park during the Winnipeg General Strike, 1919.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Foote Collection 1681, N2747.

Headlines that appeared over news stories of Winnipeg’s labour difficulties offered another way Toronto papers could report the strike. It is important to note that news editors decided the caption or headline for a story. Also, they had the power to edit all inbound dispatches about events. Thus by selective omission the meaning of the facts in the original report could be substantially altered. Often this technique was used to show the strike in a negative and sensational light. On 21 May The World captioned a front-page story “Citizen’s Army Preparing To Take Vigorous Action.” The story ran “The strike situation is rapidly approaching a crisis … Gen. Ketchen [the commanding officer of the military district in which Winnipeg was located] … has called for volunteers to a citizen’s army, and between five and six thousand have volunteered to don the uniform whenever it is necessary to combat the Bolsheviki element, which appears intent on revolution.” [52] In fact Ketchen had called out a small portion of the militia for active duty, and the reason was to assure the maintenance of law and order and the protection of private property not to ‘combat the Bolsheviki element.’ On 5 June The Telegram headlined a report “‘Down With Bolshevism!’ Thunder 10,000 Soldiers.” [53] What followed was a story about how anti-strike returned veterans were ready to teach strikers and the Red element a lesson and “to keep inside their homes.” While the headline asserted that 10,000 had voiced “Down With Bolshevism,” the accompanying story referred only to a “crowd”—not necessarily all soldiers—of eight or ten thousand. There were about 10,000 returned men in Winnipeg in total but they were split on their attitude to the strike. Not all 10,000 ex-servicemen were against the strike. As well on the same day, 4 June, another mass meeting of thousands of pro-strike veterans and workers was also underway. So the figure of 10,000 anti-strike veterans was highly unlikely. As well, as evidenced by their public gathering, these pro-strike marchers were certainly not “inside their homes.”

Between 17 May and 20 June, Atkinson published 22 editorials on and related to the strike. On 19 May The Star printed what it termed the assigned causes of the dispute. “Among the causes that are assigned are agitation of the kind that is described as Bolshevist on the one side, and on the other the refusal of certain employers to recognize and negotiate with the labour unions in their trades.” [54]

However, by 22 May, no doubt influenced by information from Main Johnson in Winnipeg, The Star’s editorial was titled “Do Not Be Misled By Names.” When Arthur Meighen, Borden’s Minister of Justice, proclaimed the strike as a “cloak” to topple authority, The Star asked for evidence of such an allegation. At the same time The Star advised that the majority of the workers in Winnipeg “entertained no idea of subverting authority or forcibly changing the form of government, but were on strike simply for better conditions of labour and the recognition of unions.” [55]

On 20 June The Star once again rejected the Bolshevik plot theory. In “Let Us Trust Our Courts,” the comment was “If there is Bolshevist or revolutionary conspiracy in Canada it ought to be proved in such a way as to leave no room for doubt or controversy … If a seditious conspiracy exists it can be proved.” [56]

Since Atkinson favored moderate craft unionism, he was not a supporter of the One Big Union, and one of the reasons was the presence of “advocates of extreme measures.” Nevertheless, The Star did not hesitate to explain the appeal among workingmen of this concept. On 10 June, in a lengthy editorial called “Trades Unionism and the Big Union” The Star furnished a comprehensive analysis of the difference between craft unionism, industrial unionism and the OBU. As the strike entered June and Plewman was able to apprise Atkinson of developments in Winnipeg on a daily basis, The Star’s comments focused on the responsibility of Borden’s government to act decisively to end the dispute. After the “midnight arrests” of the strike leaders, The Star’s editorial was “A Great State Trial” calling for the need for justice and attention to civil rights.

The Star’s final editorial on “Bloody Saturday” was “Back To The Right Way.” In it Atkinson indicted Borden and his government for mishandling the whole affair in Winnipeg, and singled out Arthur Meighen as the prime offender.

Crowd on Portage Avenue near Main Street, 10 June 1919.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Foote Collection 1673, N2739.

The role of newspapers has always been significant in providing information and views of events and in shaping public opinion. In 1919 the behaviour of the press was instrumental in determining the public’s view of the Winnipeg General Strike. What happened with the anti-strike Toronto press was reflective of almost all Canadian daily newspapers; in effect they reported and interpreted the strike, strike leaders, and workers as participating in a Bolshevist-One Big Union plot to overthrow constituted authority. This unproven conspiracy theory was then communicated to readers through a series and combination of circumstances. First, there was a background in Winnipeg of unfriendly relations between the labour paper, The Western Labor News, and the three daily papers. This relationship was exacerbated by the decision of the Central Strike Committee, as articulated by The News’ editor William Ivens, to close all three Winnipeg papers and instigate press censorship. In closing the city’s newspapers not only did The News but also all strike leaders and workers face the combined wrath of the Manitoba Free Press, The Tribune and The Telegram when they resumed publication. Moreover, their closure indirectly caused the creation of The Citizen, a paper whose very purpose was to defeat the strike. Then, by shutting down Canadian Press (CP) and imposing press censorship, the strikers alienated another news source. While the strikers had no real control over stringers and American press and services, one could argue that the imposition of censorship and curtailing freedom of the daily press was not viewed positively by any of these news groups. Finally, the circuit was complete when the news, filtered through several sources, few of whom if any sympathetic to the strike, reached outside papers and was disseminated to the public. In Toronto, with the exception of The Star, none of the dailies were pro-strike in their editorial outlook, nor had strong credentials to explain labour issues. As a result they did not hesitate to print reports critical of the strikers and the dispute. While editorial writers, news editors and journalists were immediately to blame for this situation, ultimate responsibility rested with the owners and publishers. It was these men who determined the policy of the paper and decided a certain framework in which their staffs were obliged to report and interpret events.

The Star on the other hand provided a different interpretation of the events and causes of the strike—one judged by modern historical accounts to be much more accurate. The paper explained that the strike was in essence a non-violent protest by labour to secure legitimate demands—specifically higher wages and recognition of collective bargaining as practiced by the railway running trades. While The Star conceded that some strikers were labour radicals with other reasons for confrontation, they were, it indicated, a very small minority. During the trials for the arrested strike leaders, defense lawyers extensively quoted two 23 May Star editorials “Do Not Use Black Paint” and “The Returned Soldier in Winnipeg,” to actually prove to the courts that the strike was not a Bolshevist conspiracy.

The Star’s editorial position on the strike was adopted for two reasons. First, Joseph Atkinson genuinely understood organized labour’s rising discontent, complaints and need for real changes in relations with employers after World War I. He believed in the democratic rights of workers, not only in Winnipeg, but elsewhere in Canada, many of whom were struggling to make a living. It is also true that he had strong political and business motives in judging the strike in the way he did for The Star was a Liberal paper and one that had to best rigorous competition in Toronto for readership and revenue. So Atkinson committed considerable resources and ensured that his paper gave superior and informed coverage of the general strike to its readers.

Atkinson’s commitment leads to the second reason that The Star so accurately reported and interpreted events in Winnipeg: the decision to have senior staff actually provide on the spot coverage throughout almost the entire strike. By sending first Main Johnson and then William Plewman, Atkinson ensured that The Star’s readers would receive comprehensive and uncensored dispatches from trusted and informed sources, and would not have to rely on information that was slanted against workers or hostile to the strike. As well, news and views from the two Star reporters strongly reinforced Atkinson’s editorials, giving them a foundation of facts and the integrity of eye-witness accounts. Johnson’s and Plewman’s contribution to the story of the Winnipeg General Strike was outstanding, and no other Canadian or American daily paper was able to match the quantity and quality of their reporting. They successfully overcame considerable challenges to gathering and sending the news and supplied readers in Toronto with a full, frank and intelligent explanation of the conflict in Winnipeg. Plewman in particular demonstrated stamina, ingenuity and clarity in five long weeks of reporting. In addition, both Star representatives interviewed key people in the strike and provided a fair analysis of the motives of the workers, the strike leaders, employers, and government officials. Main Johnson and William Plewman were indeed two remarkable journalists who did an extraordinary job of front-line reporting for Atkinson and The Toronto Star.

1. The OBU or One Big Union was to be a giant industrial union including the entire labouring class. It was established by labour radicals at the Western Labor Conference, called the Calgary Conference, in March 1919.

2. Elliot M. Samuels, “The Red Scare in Ontario: The Reaction of the Ontario Press to the Internal and External Threat of Bolshevism, 1917 - 1918,” MA Thesis, Queen’s University, 1972, p. 184.

3. Ross Harkness, J. E. Atkinson of The Star, (Toronto, 1963), p. 78.

4. The Western Labor News, 2 June 1919.

5. The Winnipeg Tribune, 24 May 1919.

6. The Western Labor News, 19 May 1919.

7. The Manitoba Free Press, 24 May 1919.

8. The Winnipeg Tribune, 24 May 1919.

9. The Winnipeg Telegram, 26 May 1919.

10. The Winnipeg Tribune, 2 June 1919.

11. Public Archives of Canada, Michael Dupuis Collection, George Ferguson letter to Dupuis, 24 January 1972.

12. The Toronto Evening Telegram, 26 May 1919.

13. The Montreal Star, 9 June 1919.

14. Public Archives of Canada, Michael Dupuis Collection, J. S. Woodward letter to Dupuis, 5 February 1972.

15. Public Archives of Canada, Michael Dupuis Collection, A. A. Conklin letter to Dupuis, 17 February 1972. A. A. Conklin was the son of John J. Conklin.

16. The Montreal Star, 3 June 1919.

17. The Halifax Morning Chronicle, 10 June 1919.

18. Public Archives of Canada, Canadian Press Censor Files, Volume 156, File 170, Minutes of Western Division Canadian Press Limited, 6 June 1919.

19. Public Archives of Canada, Michael Dupuis Collection, J. S. Woodward letter to Dupuis, 5 February 1972.

20. The Toronto Globe, 23 May 1919.

21. The Toronto Evening Telegram, 17 May 1919.

22. The Manitoba Free Press, 24 May 1919.

23. F. D. Millar, “The Winnipeg General Strike, 1919: a reinterpretation in the light of oral and pictorial evidence,” MA Thesis, Carleton University, 1970, p. 244.

24. The New York Times, 19 May 1919.

25. The Chicago Tribune, 29 May 1919.

26. The Toronto Daily Star, 20 May 1919.

27. Snider’s reports appeared in The Toronto Evening Telegram on 23, 29 and 31 May and 4, 7 and 10 June 1919.

28. The Toronto Star Library, “Main Johnson,” Special file, no date, and Toronto Public Library, Main Johnson Collection, “ Biographical Notes,” no date.

29. The Toronto Daily Star, 19 May 1919.

30. The Toronto Daily Star, 20 May 1919.

31. The Toronto Daily Star, 26 May 1919.

32. The Toronto Star Library, “William Plewman “, Special File, no date.

33. Private interview by the author with Richard Plewman, Trenton, Ontario, 26 February 1972.

34. Private interview by the author with Charles Plewman, Toronto, Ontario, 18 April 1972.

35. The Toronto Daily Star, 22 May 1919.

36. Richard Plewman interview, 26 February 1972.

37. The Toronto Daily Star, 31 May 1919.

38. The Toronto Daily Star, 12 June 1919.

39. The Toronto Daily Star, 23 May 1919.

40. The Toronto Daily Star, 16 June 1919.

41. The Toronto Daily Star, 27 May 1919.

43. The Toronto Daily Star, 31 May 1919.

45. The Toronto Daily Star, 23 June 1919.

46. The Toronto News, 23 May 1919.

47. The Toronto World, 27 May 1919.

48. The Toronto Globe, 3 June 1919.

49. The Toronto Evening Telegram, 17 June 1919.

50. The Toronto Times, 19 May 1919.

51. The Toronto Mail and Empire, 2 June 1919.

52. The Toronto World, 21 May 1919.

53. The Toronto Evening Telegram, 5 June 1919.

54. The Toronto Daily Star, 19 May 1919.

55. The Toronto Daily Star, 27 May 1919.

56. The Toronto Daily Star, 20 June 1919.

Page revised: 10 January 2011