by Alexander Sokalski

University of Saskatchewan

Number 46, Autumn/Winter 2003-2004

|

In the late summer of 1947 Winnipeg newspapers were proclaiming the creation of two dominions on the Indian Continent, the engagement of the Princess Elizabeth and the preparations for the Royal Wedding. On 13 August 1947 both the Winnipeg Free Press and The Winnipeg Tribune published a short item announcing a strike in Sherridon, Manitoba at the Sherritt Gordon mine. I was a little over a month short of celebrating my tenth birthday, but the strike still remains in my memory; it also remains in that of my sister and it certainly remained engraved in the memories of my father and mother. For all of us it was kept alive by a series of photographs taken by an unidentified striker sometime during the three months that the strike lasted and which my parents guarded preciously as they moved from Manitoba to British Columbia and from one house to another in Victoria.

Recently, I returned to this set of thirty-two photographs—twenty-eight of them measuring four by six inches and the remaining four, four and one-half by two and three-quarters inches. I was interested in refreshing my memory of the event behind the photographs. I was astonished to discover that this 1947 strike, which for my family and others in the towns of Sherridon and Kississing (Cold Lake) was a momentous occurrence at the time, seemed now to be almost totally unknown.

Armed with minimal information from the National Archives Reference Service, I began to go through microfilm copies of the Winnipeg Free Press and The Winnipeg Tribune and was thus able to find and read the newspaper accounts concerning the strike from its beginning to its settlement.

What follows is a brief narrative review of events based on the newspaper accounts in both dailies.

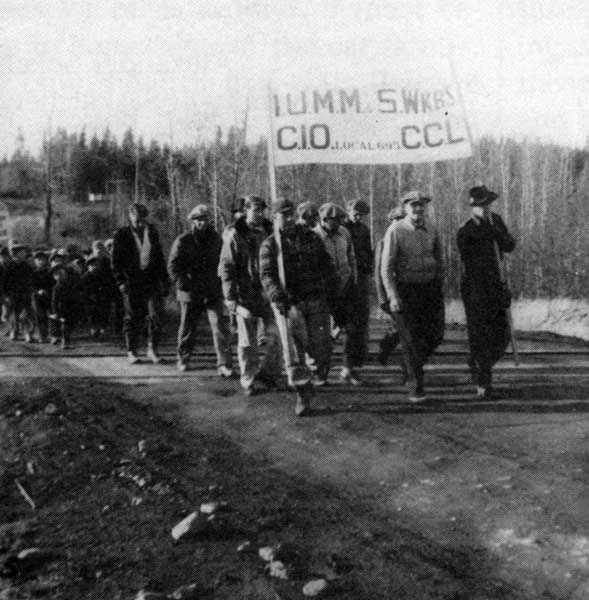

Collective march forming in Kississing.

The employees of the Sherritt Gordon mine, according to the Free Press’s front page article of Wednesday, 13 August, went on strike “in the middle of negotiations between the company and workers.” The following day, the strike is still front page news in this paper. The provincial government expected an early settlement and company officials planned to meet union leaders from the East in Winnipeg “within the next three days.” The Manitoba section of the C.C.F. voiced strong objection to extra Mounties “being rushed to Sherridon, Man.”.

The Winnipeg Tribune’s first article on the outbreak of the strike is to be found on page fifteen of its Wednesday, 13 August edition. Official notification of the strike had not been received by the Manitoba Department of Labour, from either the company or the union. The article’s author goes on to observe that the miners are striking despite having accepted the unanimous recommendations of the conciliation board of a wage increase of 13½ cents an hour, retroactive to the first of January. They are demanding a 36 cents per hour increase.

The next day this same daily, in another front page article, notes the intervention of the Department of Labour which called for an early meeting of management and the union representatives. The Deputy Minister of Labour had sent a wire to the striking miners “pointing out that their agreement embodied the Rand formula in which all affected employees must take part in a vote before action is taken”.

It is another four days before the other Winnipeg daily, the Free Press, printed a second short item on the strike and this time on page three. The strike is the result of “discrimination” and not “dissatisfaction with wage proposals,” according to the president of the Trades and Labour Council, Peter McShefley of Sudbury, Ontario. The chief executive officer of the provincial department of labour was puzzled by this charge of discrimination, professing not to know what was meant by it. This article appeared to confirm that extra police from The Pas and Flin Flon had indeed been dispatched to Sherridon.

Head of the mass march crossing railroad tracks before entering Sherridon.

Further confirmation of a reinforced police presence appeared in The Tribune in its edition of Friday, 16 August. The author informed his newspaper’s readership that police reinforcements flown in from The Pas and Flin Flon have returned to their detachments. Non-striking miners willing to return to work on the previous Tuesday returned home after surveying the pickets. As the strike entered its third day, “[b]eer parlors were closed, and stores displayed signs ‘strictly cash.’” Union spokesmen were meeting with company officials. Tourists on a Churchill Tour, scheduled to visit the underground mining operations, were not able to do so; the visit was cancelled.

No newspaper coverage between 16 August and 8 October would seem to indicate that there was little movement during this period. Then, on 8 October, on page eight of The Tribune, there appeared a news item of an impending meeting between the company head and the mine union. According to the writer, it was B[erry] R. Richards, Labour Progressive M.L.A. for the constituency, who made the announcement of this meeting to take place sometime during the week. The meeting was the result of negotiations between the union and the company. Richards stated that the company “is able to pay a base wage of 14 cents an hour” and that it had also given notice that it intended to deal with Local 695 of the International Union Of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers.

Ten days later, this same daily asserted that the Sherritt Gordon company president and managing director, at a meeting with representatives of the union local, offered to arbitrate two clauses of a new contract after the strikers returned to work The company’s arbitration offer especially concerned the retroactive pay and the Rand formula. The journalist added: “There was no confirmation Friday of a report that a number of miners were preparing to force their way through picket lines and return to work.”

Women and children crossing railroad tracks at the tail end of the march.

Then followed a lull of just over two weeks. The strike at Sherridon returned to the front page of The Tribune on 4 November. The Deputy Minister of Labour had issued a statement urging the strikers to return to work. His request was made on the strength of a letter from Pitblado,

Hoskins and Company, Solicitors for Sherritt Gordon Mines Limited. The mining company expressed its unwillingness to negotiate with the union until after the strikers resumed work. The letter singled out points of the former agreement that would need to be changed: 1) the 30-day open clause; 2) the Rand formula; 3) the retroactive wage increase. The company also expressed its willingness to arbitrate the last two objections. To allay fears that it would retaliate once the strike was called off and “‘negotiations for a new agreement would not develop normally,’“ the provincial department of labour requested that the company “‘file a letter reiterating the salient points in its attitude consistently maintained throughout the trouble.”‘

On Wednesday, 5 November, The Tribune carried on its front page a fairly lengthy piece indicating that an attempt to open the mine had occurred that morning, but the picketing miners, one hundred and fifty strong, refused to allow twenty-two workers chosen to do preliminary work before the resumption of full mine activities to enter the property. M.L.A. Richards headed the picket line and spoke for the union, stating that any attempt to reopen the mine before any agreement is reached would be resisted. The three R.C.M.P. officers on hand did not interfere. A report suggested that police reinforcements are on their way. Richards is also said to have issued a warning to the R.C.M.P., Premier Garson of Manitoba, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, the Hon. Humphrey Mitchell and the Manitoba Department of Labour “to refrain from use of the plant, as a peaceful settlement is more than ever possible.” Sixty of the more than four hundred workers at the mine had already left the area for work elsewhere. Mention was also made of a split among the workers regarding the union as the bargaining unit. More than one hundred miners were opposed to the strike at the beginning and since the company began offering its two dollars a day “standby pay”, others joined their ranks.

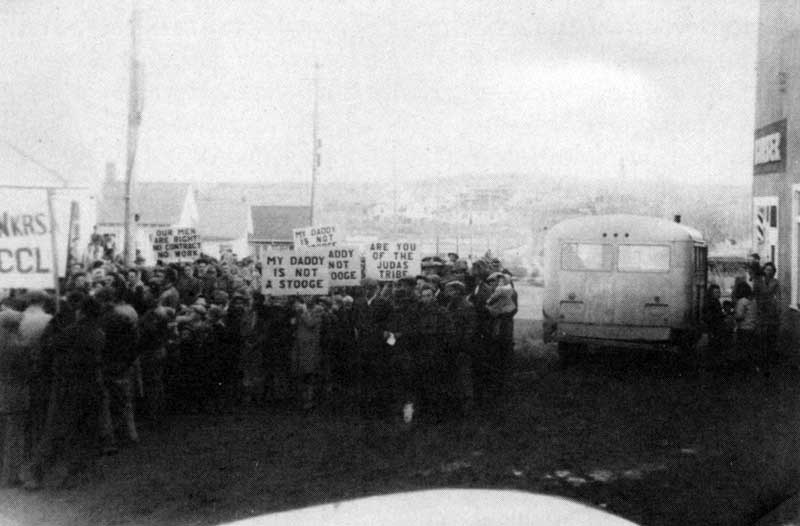

Arrival of strikers and families in Sherridon. To the right of the photo, beyond the bus and barber shop is the entry to the movie theater (not visible).

The next day both Winnipeg newspapers published a four-column, half- page advertisement from the mining company, in the Free Press on page twenty-two and in The Tribune on page twenty. The Sherritt Gordon Company’s statement presented its point of view “with regard to the illegal strike of its employees.” This position statement consists of five letters dated 1 October, 9 October, 17 October, 1 November and 4 November.

At some point between 7 and 13 November, the Sherritt Gordon Company was granted an interim injunction. On 7 November, the readers of The Tribune were informed that the company would probably be seeking an injunction On 13 November, readers of the Free Press learned of the existence of the injunction in an article on page eight which reviewed resolutions adopted by the C.C.F. provincial council. The council deplored “‘the action of the Manitoba courts in granting an interim injunction to the Sherritt Gordon mining company” and censures “‘the Manitoba government for continuing the legality of such injunctions.’”

The strike continued despite the injunction issued by Mr. Justice W. J. Major of the Manitoba Court of King’s Bench and picket lines remained in force. The Free Press of 14 November notes also that forty R.C.M. P. had been moved to The Pas, fifty miles south of Sherridon. Enforcement of the injunctions against fifteen specific defendants are said to be delayed because the deputy Sheriff has been unable to locate the individuals named. Twenty-two men showed up for work but were turned back “when a picket line placed at 150 barred the way”. There was no violence and “both pickets and would-be workers appeared on good terms.” The sergeant and constable from the Sherridon R.C.M.P. detachment, the only police in town, made no attempt to intervene. Concerning other police, the article adds: “Provincial officials said the 40 officers at The Pas had been moved there to there to be on hand in the event of ‘any breach of the peace’”.

Strikers in Sherridon, probably sometime during the month of October.

The front page article in the following day’s edition claimed that forty R.C.M.P. are now in Sherridon “prepared to step into the picture should any breach of the peace result from the present deadlock between striking mine employees and the SherrittGordon limited management”. Pickets continued to be posted at the mine entrance. On the previous day, some 95 men had approached the mine but were stopped by an estimated 150 man picket line. The R.C.M.P. officer in charge of the town’s detachment warned the pickets that “they were breaking the law and disobeying a court injunction” but the line held firm. The international representative of the unionis reported to have stated that “‘as soon as the company gives proper recognition to the certified bargaining agents, Local 695’“ a settlement can be reached and work can resume immediately. The article recalled that the reason for the strike is wages and remarks that several—no specific number is given—of the approximately four hundred miners initially involved have left to find work elsewhere. The deputy sheriff seeking to serve the injunctions of fifteen persons named did not find them at home and was barred from entering the union hall. As to the reenforced presence of the police, the article reiterated in its conclusion that this is “understood to be a safeguard against any disturbances which might flare up”.

An accompanying front-page item observes that the government of Manitoba will not take any steps against the injunctions issued against striking employees of the Sherritt Gordon mine. The request for intervention had been made by various union offices from all over Canada, in letters and telegrams sent by union locals. The Manitoba attorney general’s office, in reply, indicates that it cannot interfere “‘with the courts in the exercise of its judicial function—, nor curtail “‘its independence of action”’ since this “‘would constitute a grave breach of those well established fundamental principles so essential for the maintainance [sic] of a true democracy’”. The attorney general further declared that those against whom the injunctions are to be served have gone into hiding and that there were no extra police in the area the day before.

The fourteen-week old strike was finally called-off following the recommendations of Pat Conroy, secretary- treasurer of the Canadian Congress of Labour, and, according to both the Free Press and The Tribune, the “heads of unions affiliated with the Winnipeg labor council”. The Tribune article heralding the end of the strike appeared on that newspaper’s front page, that of the Free Press is to be found only on page seven.

Strikers at the Sherridon train station.

Before the decision to end the strike was taken, The Winnipeg Tribune and the Winnipeg Free Press would both publish editorials, the Free Press on 12 November and The Tribune three days later, presenting the case of one Frank W. Carr, a non-union employee of the Sherritt-Gordon company, whose application for unemployment was disallowed on the grounds, that he was “directly interested in the labor dispute which caused the stoppage of work.” Also disallowed was Carr’s other claim that he was helping to finance the dispute since he paid union dues because of the Rand formula which called for such payment from both union and non-union workers. The editorialist of the Free Press argued in “Rights Vio lated” that Carr’s right “against infringement either by the laws of the state, or by agreement entered into between groups within the state” had been violated. The Tribune’s much shorter editorial “A Rankling Injustice” argues that “it is bad enough to be muleted of $2 a month against one’s will without having it later advanced as a reason for withholding unemployment insurance benefits as well.” If and when Manitoba frames a labour code, the Rand formula should be made illegal. The Carr case, it concludes, “leaves a rankling sense of injustice in all who read it.”

On the editorial page of the 19 November edition of The Tribune appear two pieces, one, the editorial “Lawbreaking is Lawbreaking” and the other a brief history of the work stoppage, “Trouble at Sherridon”. The editorial attacked the open defiance of the injunction displayed by the picketers, arguing that laws need to be obeyed at once. It censures M.L.A. Richards for encouraging and taking part in “such irregularities” and accused him of having “shown remarkably little concern for upholding the law”. It goes on to praise the stance adopted by the Attorney General of the province in refusing to interfere with the court injunction despite the request of various union officers and then blasts both these officers and the picketers, declaring that their attitude is proof “that some members of unions think that the status of being on strike places them above certain provisions of law. Such an attitude cannot be tolerated in Canada.” The companion piece outlining the work stoppage at Sherridon begins by quoting an excerpt from the proceedings of the Court of Referees in connection with the Carr case mentioned earlier and with regard to the illegality of the strike. It then cites another part of the decision which presents the different steps to be taken “to effect a revision of a collective agreement before a strike is to take place”. There follow five short paragraphs which sketch the events having occurred between 6 and 18 November.

I recall my mother and father talking of the strike and how it was progressing. I have memories of my father visiting neighbours in an effort to convince them not to sign-on for work. I remember my father recounting how he had stood up at the union meeting at which the decision was reached to return to work, arguing against the conditions laid out. One angry striker turned on him accusing this “small bohunk” of being one of the instigators of the strike. At this point a fellow striker came to my father’s defence and pointed out that, in fact, he had been opposed to the strike and had counselled his union brothers to make sure that their position was solid before they did go out. Although not in entire agreement with the strike he maintained that solidarity with his striking comrades was the right and honourable stance. In the late 1980s, when my sister settled in Campbell River, B.C., she met there the son of the man who had defended my father at that union meeting. And once again my father, almost ninety by then, brought out his stories of the strike and he and my mother reminisced over the photographs recording the event.

Sherridon, May 2003. The four storey Hotel Cambrian still remains. The movie theatre was located where there is now a vacant lot on the right side of the photo.

Over the years, my own memories have certainly grown dimmer but I do recall the organized marches from the Union Hall in Kississing to Sherridon, to which the photos, now in my possession, bear silent witness. These appear to have been taken in late September or early to mid-October. In them the viewer sees the strikers and families gathering together in the town of Kississing, then the march to Sherridon, the union executive and strike committee followed by the younger children, the older children, members of the women’s auxiliary and finally the mass of strikers. I recognize my father, the children’s marshal, and myself in one photo of the children’s group. Absent from the pictures are both my sister and my mother. (Only recently, my sister informed me that they had both remained behind at the hall, my mother occupied with preparing food for the marching strikers and my sister because my mother considered her too young to make the mile and a-half or two mile trek between the towns and back.) Some photos capture only the miners holding a banner with a direct reference to the company’s offer of a two dollars standby pay, an offer made on 17 October. The four smaller format photos show snow. These were taken at the Sherridon train station, probably in early November, as the striking miners awaited the arrival of police reinforcements from The Pas. The Winnipeg Tribune notes on 5 November that “[t]wo inches of snow fell at The Pas during the night”. This collection of photographs provides a human face and a human presence lacking in contemporary newspaper accounts.

The mine at Sherridon closed in 1951. Some six or seven winters preceding the closure, the company began building a heavy freight winter road between Sherridon and Lynn Lake where it was developing its new mine. Houses from both Sherridon and Kississing were loaded onto platforms fitted with skis and transported some 200 miles north-east to the new site. The present web site for Lynn Lake states: “A fishing company bought the [Sherridon] site but all that remained was an overgrown golf course and empty streets leading nowhere.” Yet more of Sherridon and Kississing remained than that overgrown golf course and those empty streets; left behind were the abandoned mine shaft and the ecological damage resulting from the mining operation, carried to other places in the dominion were personal artefacts such as photographs. And, of course, these Manitoba towns remained in memories, memories which by now are either completely stilled or faded with time. On 18 July 2001, the province of Manitoba embarked on a program of cleaning up and rehabilitating the abandoned mines of the North, among them that of the Sherridon site. Refreshing my own memory of the 1947 Sherritt Gordon mine strike has, I hope in some small way, permitted me to rehabilitate a tiny bit of almost unknown Manitoba labour history which the photographs in my possession will continue to preserve silently.

Canada Gazette, December 1947, p. 1873.

Winnipeg Free Press:

“Sherridon Workers on Strike,” Wednesday, 13 August 1947, page 1.

“Early End Of Mine Strike Foreseen,” Thursday, 14 August 1947, page 1.

“Union Charges ‘Discrimination’,” Monday, 18 August 1947, page 3.

“Use of Police at Sherridon Defined,” Thursday, 6 November 1947, page 9.

“Sherritt Gordon’s Point of View with regard to the illegal strike of its employees,” Thursday, 6 November 1947, page 22.

“Rights Violated,” Wednesday, 12 November 1947, page 15.

“Courts, Government Rapped for Injunction,” Thursday, 13 November 1947, page 8.

“Attempt To Open Mine Expected At Sherridon,” Friday, 14 November 1947, page 1.

“Mine Pickets Ignore Court Injunction,” Saturday, 15 November 1947, pages 1, 10.

“Sherridon Mine Strike Settled; Firm and Union Start Talks Soon,” Wednesday, 19 November 1947, page 7.

The Winnipeg Tribune:

“Men Strike At Sherridon,” Wednesday, 13 August 1947, page 15.

“Meet of Mine, Strikers Called,” Thursday, 14 August 1947, page 1.

“Extra Police Quit Sherridon,” Friday, 16 August 1947, page 3.

“Sherritt Gordon Head To Confer With Mine Union,” Wednesday, 8 October 1947, page 3.

“Sherritt Offers Arbitration If Strikers Return,” Saturday, 18 October 1947, page 9.

“Wilson Urges Sherridon Men To Return To Jobs,” Tuesday, 4 November 1947, page 1.

“Sherridon Pickets Balk Men’s Return,” Wednesday, 5 November 1947, page 1.

“Sherritt Gordon’s Point of View with regard to the illegal strike of its employees,” Wednesday, 5 November 1947, p.

“Quizz Province On Protection At Sherritt Mine,” Friday, 7 November 1947, page 1.

“A Rankling Injustice,” Saturday, 15 November 1947, page 6.

“Sherridon Mine Talks Expected As Men Return,” Wednesday, 19 November 1947, page 1.

“Lawbreaking is Lawbreaking,” Wednesday, 19 November 1947, page 6.

“Trouble at Sherridon,” Wednesday, 19 November 1947, page 6.

Articles not found:

Flin Flon Miner, Tuesday, 7 October 1947.

Northern Mail, Wednesday, 8 October 1947.

Page revised: 28 October 2012