|

The following text is taken from a brochure recently published by the Historic Resources Branch of Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Citizenship. The brochure, which marks the 125th anniversary of Manitoba’s entry into Confederation, summarizes the pivotal events of 1869-1870 and provides information on a number of sites in and around Winnipeg associated with the Resistance. It is reproduced here with the kind permission of Culture, Heritage and Citizenship.

On a snowy day in October 1869, a group of nineteen unarmed Métis riders took a major step in changing the course of Manitoba’s history. Confronting a survey crew that was staking out land west of the Red River for the anticipated arrival of Canadian settlers, the Métis stepped on the surveyors’ chain, signalling their intention to oppose the distant Canadian Government’s plan to annex the west for agricultural immigration.

For the previous year the residents of the Red River Settlement had been apprehensive as the Hudson’s Bay Company prepared to transfer control of present-day western Canada to the Canadian Government. While all the inhabitants of Red River—Scottish, French, Métis, English-speaking Métis and Aboriginal—faced the impending change with anxiety, it was the French-speaking Métis, concerned about land ownership and language rights, who took action to oppose the land transfer. Louis Riel, who led the Métis riders that fateful day in October, provided focus for the discontent.

Louis Riel, circa 1873 (note misspelling of his surname)

Source: Archives of Manitoba

Louis Riel was born in the Red River Settlement in 1844 and educated in St. Boniface and Montreal. Chosen as secretary of the Comite national des Métis, he later became President of the Provisional Government, which led the struggle for a negotiated entry of the Red River Settlement into the Confederation, as a province rather than a territory. While Riel’s militia kept the Canadian representatives from occupying the Settlement, it was Father Noel-Joseph Ritchot, parish priest of St. Norbert, who travelled to Ottawa with two other residents of Red River to negotiate the terms of the Manitoba Act of 1870. This Act, which conceded provincial status to Manitoba, also confirmed political rights, existing land ownership, use of the French language, and separate state-supported Catholic and Protestant schools.

Not everyone at Red River supported Riel and Ritchot. Opposition was centred around the Canadian Party, which was prepared to sacrifice the existing way of life in Red River in favour of the economic rewards to be reaped from the west with settlers from Ontario.

Although the struggle for the creation of Manitoba ended on 15 July 1870, with the proclamation of the Manitoba Act, the bitterness between the two opposing groups continued. Canada had sent a military expedition, under the command of Colonel Garnet Wolseley, to oversee the transfer of power from the Provisional Government. With the arrival of the Wolseley Expedition at Red River in August, Riel and some of his followers were forced to flee the country. Because the Canadian Government repeatedly denied him amnesty for his role in the Resistance, Riel was unable to represent his people officially, even though they elected him to the House of Commons three times. He remained in exile until 1884, when he returned to present-day Saskatchewan to lead the Métis in the North West Rebellion. For this action, Riel was found guilty of treason and hanged in Regina on 16 November 1885. A controversial figure, Riel was denied his place in Canadian history until 1992 when he was formally accorded status as a founding father of Manitoba.

Louis Riel (seated, centre) and members of his Provisional Government, 1870.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

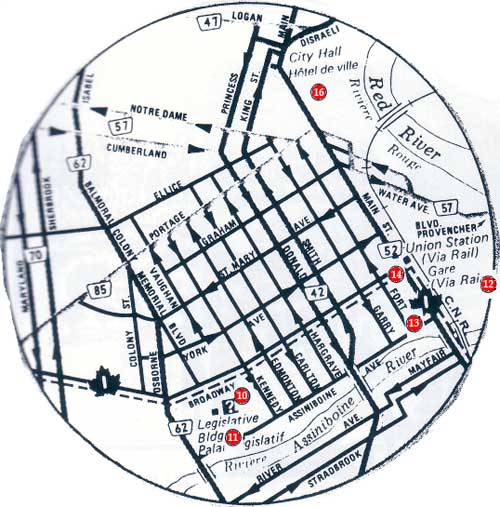

Many sites around the City of Winnipeg are associated with the events of 1869-70. The 16 sites high-lighted in this brochure are located at nine different venues. They include a variety of interpretive experiences—historic buildings, statues, monuments and markers that will help you understand the progression of events that led to the creation of a new province. The sites are organized, as much as possible, in a circular route, designed to be visited in one day, or if one prefers, individually. Together they tell the story of the Red River Resistance.

|

1. |

St. Boniface Museum, 494 av de Tache, St. Boniface |

|

2. |

College universitaire de Saint-Boniface, 200 av de la Cathedrale, St. Boniface |

|

3. |

St. Boniface Cathedral, 190 av de la Cathedrale, St. Boniface |

|

4. |

Riel House National Historic Site, 330 River Road, St. Vital |

|

5. |

Riel-Ritchot Monument, rue de l'Eglise and St. Pierre, St. Norbert |

|

6. |

La Chapelle de Notre-Dame du Bon Secours, rue de l'Eglise and St. Pierre, St. Norbert |

|

7. |

Place Saint-Norbert, 3514 Pembina Highway, St. Norbert |

|

8. |

St. Norbert Provincial Heritage Park, 40 Turnbull Dr., off Pembina Hwy., St. Norbert |

|

9. |

Don Smith Park, Corner of Scurfield Blvd. and Fleetwood Rd, Whyte Ridge |

|

10. |

Legislative Building Grounds, Corner of Broadway and Kennedy St. |

|

11. |

Assiniboine Riverbank Park, Legislative Building Grounds |

|

12. |

The Forks National Historic Site, northeast of the Children's Museum, The Forks |

|

13, |

Bonnycastle Park, Assiniboine Ave. at Main St. |

|

14. |

Fort Garry Gate Park, Entrance south of Broadway off Fort St. |

|

15. |

Norquay Park, Beaconsfield St. at Lusted Ave. |

|

16. |

Museum of Man and Nature, 190 Rupert Ave. and Main St. |

French-speaking St. Boniface is the birthplace of Louis Riel as well as his final resting place. A bust in front of the St. Boniface Museum [1], a statue on the east side of College universitaire de Saint-Boniface [2] and a plaque on the western wall of St. Boniface Cathedral [3], where he first denounced the actions of the Canadian Government, all pay homage to Riel’s role as a spokesman for his people. Riel’s tomb and that of his compatriot, Ambroise Lépine, who, like Riel, suffered persecution for his actions in 1869-70, are located in the cemetery in front of the Cathedral. The nearby St. Boniface Museum displays important artifacts of Riel’s life, such as his original coffin, as well as depictions of Francophone and Métis life on the prairies.

View of St. Boniface Mission, 1869.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

Ambroise Lépine

Source: Glenbow Archives

In December 1885, Louis Riel’s body was brought in secret to this, his mother’s home [4]. Costumed guides will interpret the life of Riel’s family during the 1880s.

A Métis settlement dating back to 1822, St. Norbert was the centre of the early events connected with the Resistance. It was here, on 19 October 1869, at a public meeting held at St. Norbert Roman Catholic Church, that the Métis elected the Comite national des Métis with Louis Riel as secretary. As their first act the Comite sanctioned the erection of a barrier across the Pembina Trail to keep out unwanted emissaries of the Canadian Government. Near the present church stands the Riel-Ritchot Monument [5]. The rear of the monument provides a summary of the events that took place at St. Norbert. Across the street from the church is La Chapelle de Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Secours [6], built by Ritchot and his parishioners in 1875 to thank the Virgin Mary for her divine assistance in 1869. In 1906, to commemorate the raising of the barrier or “La Barriere”, L’Union Nationale Métisse de St. Joseph erected a stone cross near the site of the original barrier by the La Salle River.

Today this monument can be seen at Place Saint-Norbert [7]. Across the La Salle River from St. Norbert, at St. Norbert Provincial Heritage park [8], two commemorative plaques interpret the significance of St. Norbert and of La Barriere. As well, the heritage houses there represent the different phases of St. Norbert’s history.

Southwest of this site [9], on 11 October 1869 Riel’s men forced surveyors to halt their work until negotiations with Canada were completed. A provincial plaque interprets this event.

At the corner of Kennedy Street and Broadway a bust of George-Etienne Cartier [10], a Father of Confederation, honours his role in guiding the Manitoba Bill through the Canadian Parliament in 1870. On the riverbank south of the Legislative Building a provincial plaque as well as a planned new statue of Louis Riel [11] are fitting tributes to his role in the founding of Manitoba.

At Winnipeg’s most popular site, one can experience the City’s past as well as its present. A federal plaque at The Forks National Historic Site [12] describes the events which created the “postage-stamp province” called “Manitoba.” A short walk west along the River Walk provides access to Bonnycastle Park [13], located on the former site of Upper Fort Garry. It was occupied by Riel’s followers on 2 November 1868, and thereafter served as the administrative centre for the Provisional Government. Riel’s men quietly vacated the post on 24 August 1870, a few hours before the arrival of a Canadian military force led by Colonel Garnet Wolseley. The significance of the Wolseley Expedition is depicted in a provincial plaque here, as well as in interpretive panels at Fort Garry Gate Park [14], located one block north on Fort Street. This park contains the remnants of Upper Fort Garry, where opponents of the Provisional Government were imprisoned. It was here, on 4 March 1870, in one of the most controversial acts of the Resistance, that the Provisional Government executed one of its most vocal opponents, Thomas Scott. A provincial plaque explains Ambroise Lepine’s role in the Resistance.

Upper Fort Garry with Red River Expeditionary Force at drill, 1870.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

A view of the interior of Upper Fort Garry, circa 1870.

Source: Hudson's Bay Company Archives

While negotiations to settle the dispute over Canadian occupation of the West continued in Ottawa, at Red River opposition to Riel’s course of action was centred in the Canadian Party, led by John Christian Schultz. A plaque explaining Schultz’s role in the early history of Manitoba is located in Norquay Park, the site of his former residence [15].

A visit to Manitoba’s finest museum [16] will increase your understanding of the history of the Red River Settlement and the events of 1869-70.

Page revised: 14 May 2010