Introduction by Cecile Clayton-Gouthro

Clothing and Textiles Department, University of Manitoba

|

The celebration of Manitoba’s 125th Anniversary will be shared by a diverse community, many wearing some form of distinctive dress. Images of Manitobans are closely connected to the clothes we wear, clothing that speaks about who we are and where we come from. Robin Crysdale and Nicole Davies, the authors of the following short papers, are friends. They are currently completing their degrees in Clothing and Textiles at the University of Manitoba. The family “portraits” they have created reflect their different backgrounds and illustrate two varying components of Manitoba’s cultural heritage.

Promoting the successful business image. Globe and Mail, October 1, 1979.

On March 4, 1977, The Winnipeg Tribune printed an article with the following excerpt “... But he’s still so new to the West that he’s garbed in the “uniform” of Toronto’s Bay St. and Montreal’s’ St. James St.–a dark pin-stripe suit with vest (bottom button properly undone), white shirt and unmodishly narrow, discreet tie.” (H. L. Mardon, 1977, p. 15). The man that Mardon wrote about was my father. Our family had recently moved to Winnipeg from Montreal and my father’s conservative appearance was considered the “uniform” of the eastern business community. This “uniform” interpreted my father’s commercial work ethic and I learned that clothing can communicate many messages.

My father appreciated good service and quality from certain traditional stores in Toronto. He had his suits tailor-made in Toronto at Eli’s, where he also purchased his dress shirts. His work shoes came from back’s, a store specializing in footwear for the business man. It didn’t matter where we lived, whether it was Montreal or Winnipeg, if Dad was on a business trip to Toronto and needed a new suit or shoes he went back to his conventional haunts.

When my father dressed for work it was an orderly, thoughtful process. He used appearance management to achieve a serious business-minded presentation and every aspect was considered. The business suit was important in conveying the message that my father knew what he was doing and was a hard working man. There was simplicity of line and classic elegance creating a ‘no non-sense’ approach to his appearance.

It would begin with comfortable underclothing and knitted wool socks in executive length, held up with garters. The garters kept the socks tight and unwrinkled at the ankles when my Dad would sit down and stand up. Then out of the closet would come a long sleeved dress shirt with a fused, lightly starched collar. The shirt was crisp white and made of 100% cotton. Some of the shirts incorporated buttons on the cuffs and others used cufflinks. Next came the tie, narrow and made of silk, woven in somber colours with small, discreet motifs and fastened into a four-in-hand knot.

Robin Crysdale's father in his business attire, 1970s.

The suit would be hanging on a valet and my father always made a last minute check to make sure there was no fluff or hairs on the jacket. Every night when he came home he would brush the jacket and pants, letting them air out before being put away in the closet. The suits were all 100% wool and fabricated in various weights for summer or winter wear. They were dark in colour and some incorporated pin striping.

The trousers were constructed with two side pockets and two back pockets, one back pocket having a button. There were no pleats or belt loops and the pants were held up by suspenders. The vest was in the same material as the pants and the outer fabric of the jacket. The vest was lined in the same material as the jacket lining.

The jacket was single-breasted with a notched collar. The left breast pocket and the two lower pockets were welted. There were flaps on the lower-pockets that could be tucked in to change the appearance of the suit jacket. There was also a deep inside breast pocket that could hold a cheque book or wallet. The sleeves had a false seam near the cuff with three or four buttons attached. The jacket was fully lined and had a back vent. Shoulder pads were placed in the jacket but were not heavily padded. Freshly polished shoes followed the donning of the suit. They were laced black leather oxfords with a softly pointed toe. My Dad’s shoes were expensive but he carefully maintained them by reheeling and resoling them at appropriate times. The only accessories he wore comprised his glasses, a tasteful gold watch, a gold wedding band, and when the shirt required it, cufflinks.

If a man wanted to be taken seriously in the business community he dressed the part. Retailers such as the Bay (as shown in the accompanying advertisement from the period) promoted this attitude, using carefully chosen words that connected “success” with appropriate business dress. This constituted dark colours and classic simplicity in the styling of the suit and as the newspaper writer Mardon noted in 1977, the presentation was completed by leaving the bottom but-ton of the vest undone. The ‘look’ was understated and definitely not frivolous. You might venture to say this was typical Canadian business attire with its historical roots in, the somber and conservative British appearance.

Today my Dad lives in Toronto and is still going to work in a business suit. The “uniform” has evolved to become more casual and it is now minus the vest. My father’s suits and ties are also lighter in colour. On a cognitive level I learned a great deal about the inherent quality of good fabrics and styling. My Dad also taught me a lot about using clothing as a vehicle of communication. I acquired the knowledge that classic clothing is an investment and an uncluttered, simple appearance goes a long way in conveying messages to the people around you.

Robin Crysdale

University of Manitoba

Robin’s father’s “uniform” is representative of English traditional menswear, closely associated with the status of the wearer—a successful businessman. Nicole’s Baba shows us another side of Manitoba’s peoples, those who came from Eastern Europe.

Roused at an early hour, I stumbled towards my Baba and Dido’s garden. Their home, located in the middle of the countryside seemed to be quite isolated. Fields surrounded their small yard and all that could be heard were the sounds of nature. Having lived their lives as farmers, this reclusive setting helped define their lives. They had no need or desire to be part of city life and the rigors it entailed. I sat down at the giant picnic table which was already laden with fresh vegetables from the garden. Today was the day we would make borscht and everyone’s service was required. Milling around was my Baba, my mom, my aunts and several of my female cousins. A few of these women would be wearing scarves on their heads, some for practical reasons and some for aesthetic reasons. But whatever the role of this headwear, I remember it being worn by many of my female relatives. The babushka is a distinctive article of clothing that played a prominent role in my family.

My great Baba and Dido Trach came to Canada from Poland and my great Baba and Dido Paradoski immigrated from the Ukraine. They settled in the prairie provinces and established themselves as farmers. My mother recalls both of my great Babas always wearing babushkas. They consisted of a piece of material, fashioned into the shape of a triangle and secured on the head. Whether fastened underneath the chin or at the nape of the neck, the babushka covered one’s head, holding the hair away from the face. My mother remembers Baba Paradoski wearing a babushka every day, all year round. Since this headwear was donned every morning, it most likely served a very practical purpose. My mother believes it may have also just developed into a habit. Darker colored babushkas, often black, were worn in the winter, while lighter colors were reserved for use in the summer. If the babushka had a print, it was generally a small floral pattern. Cotton was the most easily attainable fabric at the time.

My Baba and Dido settled in rural Saskatchewan and started their lives as farmers. I recall that my Baba sometimes wore a babushka. For her it was not an essential part of daily attire, but it was worn when there was work to be done. For my Baba, the babushka was a practical and functional addition to the wardrobe. When working out of doors, it kept her hair off of her face and protected her ears from the wind. During the summer, the babushka offered valuable protection from the glaring sun as it helped ward off heat stroke. The babushka also absorbed perspiration, preventing it from rolling into the eyes. A heavier babushka was worn throughout the winter as protection from the cold. It is probably for these practical reasons that my great Babas wore babushkas daily. There is not one particular color or print that I recall as being predominant. Rather, my Baba would use whatever material was readily available. Baba would sometimes make her babushkas out of old clothes or she would bleach old flour and sugar sacks and use them as material.

|

|

|

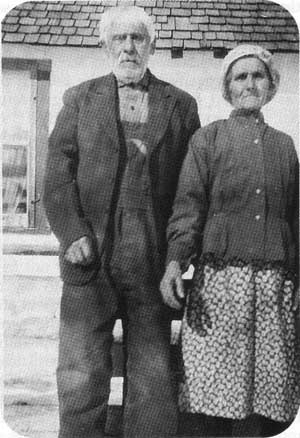

Mr. and Mrs. Paradoski, Nicole Davies' great Baba (grandmother) and Dido (grandfather) |

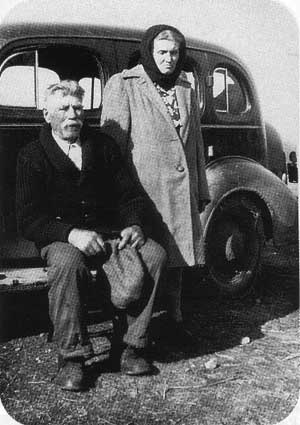

Mr. and Mrs. Trach, Nicole Davies' great Baba (grandmother) and Dido (grandfather) in 1947. |

I also recall my mother and her sisters as wearing a form of head scarf, reminiscent of my Baba’s babushka. These women also donned this form of headwear for practical reasons. It was an excellent way to hold hair away from the face whether indoors or out. For my mom and her sisters, the babushka also served an aesthetic purpose. The babushka was used to cover messy hair or a head full of curlers. These head coverings were frequently made from synthetic fibers and offered a transparent, filmy look.

Even today, my cousins and I carry on the fundamental idea of the babushka, through the usage of bandanas. Tied in the same manner as a babushka except with the loose end tucked in, the bandanna also serves a practical purpose. We, however, use it mostly for it’s aesthetic value. I have often worn a bandanna when my hair is messy. Also, bandannas worn as babushkas come in handy to protect colored hair from prolonged exposure to sunlight and they are extremely useful to hide your hair when it has accidentally been dyed the wrong color.

The reason why my Baba’s babushka retains such a distinct role in my mind is because it’s use has been carried on through many generations. From pictures of my great Babas with babushkas, to seeing my cousins wear bandannas even today, my Ukrainian background is reinforced. While my immediate family does not practice many Ukrainian traditions, the babushka has managed to retain its importance. Despite the different fabrics, colors, functions, and ways of wearing this head scarf, to me it will always be identified as the babushka.

Nicole Davies

University of Manitoba

Page revised: 1 August 2015