by Sarah Carter

University of Manitoba

Manitoba History, Number 11, Spring 1986

|

Riel House.

Source: Parks Canada

An inventory of Manitoba’s historic sites, exhibits and plaques might convey the impression that the history of the women of this province has been almost disregarded. The accomplishments of a few women active in social and political reform and women pioneers in the professions have been recognized, but the careers of these leaders were distant from the lives of the majority of women, just as the average worker or farmer had little in common with the celebrated men of business and politics who have traditionally been the subjects of commemoration. At first glance it might appear that Riel House, the family home of Louis Riel, and Dalnavert, the residence of Sir Hugh John Macdonald, simply belong to the conventional “house-of-a famous-man” category. Although both structures were saved from the wrecker’s ball largely because of the distinguished men who once trod their floors, these restored residences in fact tell us a great deal more about the women occupants who were responsible for creating and maintaining the home environment. While relatively little is known about the personal history of the women of the Riel and Macdonald households (at least as compared to the data available on the men), their homes reveal a good deal about day-to-day family life, the woman’s role, and about housework, the major activity of half the population.

Riel House and Dalnavert, both restored to the late nineteenth century, provide an opportunity to observe two distinct domestic settings in which women presided, as they are representative of two different social economic and cultural worlds. One way of life had prevailed in the West for many years, while the other was a more recent implantation. The two homes offer a glimpse of domestic life during a critical period in Manitoba’s past, most often described as a time when the old order of the Métis lost supremacy, and the province was transformed into an Anglo-Ontarian community. The names Riel and Macdonald, indelibly linked in Canadian history, are symbolic of the old and new order. Their homes provide evidence that while this transition to an Anglo-Ontarian province may have taken place in the corridors of economic and political power, in the realm of domestic life, one culture did not supplant the other, rather the two ways of life co-existed, separately.

Parks Canada has restored Riel House to the early spring of 1886, some months after the body of Louis Riel had lain “in state” for two days in the home. Twelve people lived in the house at that time, six children and six adults. Louis’ mother, Julie Lagimodiere Riel, was the matriarch of the household. She was a devoutly religious woman who, before her marriage (out of obedience to her parents) had hoped to become a nun. She had eleven children, a not unusually high number in a society where the concept of voluntary motherhood was not countenanced. Her youngest two sons, along with their wives and children, resided with her in 1886, as did Louis’ widow, Marguerite, and her two children. The Riels were a closely-knit family within a community which accepted collective responsibility for the welfare of its members, and it was common for several generations of family to live under one roof. Young Métis couples often spent some time with the husband’s family before acquiring their own home. Correspondence between members of the Riel family reveals their deep affection for one another, and deaths within this circle, such as that of Louis Sr. in 1864, Marie in 1873, Charles in 1874, and Sister Sara in 1883 were occasions of the deepest grief. In 1886 the Riels were once again lamenting the death of one of their family, and the mourning cross on the roof proclaimed this to the community. The mourning period extended as Marguerite died of consumption in May of 1886 at the age of twenty-five.

Source: Parks Canada

Riel House, on river lot 51 in the parish of St. Vital, is situated on one of the numerous necks of land thrown out by the meandering Red. It was a pleasant rural setting that was combined with some of the advantages of village life, as the farm homes of the Métis were in close proximity to one another, along the river. The heavily-treed riverbank is about 400 metres from the front door of the Riel home. The house is an example of vernacular architecture, or folk housing. It was designed and built by the occupants, who were not concerned with mimicing fashion, or presenting a stylish, imposing face to the world. The home was intended to provide basic shelter, and it reflected utilitarian and practical considerations rather than preoccupation with aesthetics and fashion. Joseph Riel, younger brother of Louis, built the log home in 1880-1881, in the standard Métis style known as “piece-sur-piece de charpente” or “poteau sur sole” (post on sill) or “Red River Frame.” Although it was built at relatively little expense, it boasted more amenities than Métis homes built not many years earlier, reflecting the availability of new tools, finished lumber, and other materials. The home was sided with clapboard, the roof was shingled, there were glass panes in the windows, floorboards, and a ceiling of finished planks. The interior was partitioned into several rooms, and the iron stove had replaced the traditional clay-plastered fireplace.

Doors of prairie homes like Riel House swung to the inside, as it could be difficult to exit in winter if several feet of snow had drifted against an outswinging door. Here there was no porch or vestibule; visitors entered immediately into the main room (la salle), which for the winter months was the only common room for the family, serving as kitchen, dining room, sitting room, and a sleeping room at night. Two bedrooms were off this main room, and the upstairs was also used as sleeping quarters. During their waking hours, family members were seldom separated from one another in this house, nor was there any division between public and family interaction. Living space in early prairie homes shrank considerably during the cold months as additions and lean-tos were abandoned, and the stove or lamp became the focus of family activity. In a household full of adults, young children and frequent visitors, winter’s confinement meant that individual privacy could rarely be found, but the people enjoyed a high degree of spontaneous family intimacy. As the weather warmed, and the days grew longer, an additional room and the outdoors expanded living space. An annex, which overlooked the river trail was a storage area in winter but a kitchen in the summer months when the cast iron stove was transferred there.

The furnishings of the Riel home were well-crafted homemade items that were plain and functional. They reflected a mixture of French-Canadian and native influences. The native heritage is most evident in the hammock, or in Cree “Wewepisoni,” in which a baby was secured with the aid of a “ceinture flechee” or “L’Assomption” sash, worn by Métis men over their coats. Storage space was at a premium in this house as there was only one built-in closet. Trunks beneath each bed accommodated some personal effects, but for the most part there was no opportunity to conceal or camouflage the tools, utensils and supplies required for everyday living. Family photographs were prominent in the Riel home. A mourning cloth is draped on the large portrait of Louis that hung by his mother’s bed, and her black shawl is a further reminder that in 1886 the family was still mourning the death of Louis, and following the prescribed behaviour.

Religious iconography dominated the decor of the Riel home. These included rosaries, crosses, small figures of Jesus and Mary, images of the Sacred Heart of Mary, and the Virgin and Child, and portraits of Pope Pius IX and Mgr. Bourget. Some adorned the walls and others were displayed on small, high, altar-like shelves. Beside each bed was a “benitier” containing holy water. These pieces and images were exhibited because they were the prized possessions of the family and because it was believed that they were imbued with the power to bring good fortune and ward off evil influence. Religious iconography conferred a sacred aspect on the home and family, and helped to educate the young.

The Métis were a religious people, and the Riels were a particularly devout family. The lives of the women especially revolved around a daily attendance at mass and constant prayer. The ideology of the church defined the role of women in the Riel house, and in Métis society. To a great extent, religion was seen as the domain and responsibility of women, and emphasis was placed upon their duty to nurture a pious atmosphere in the sanctuary of the home, and to serve as teacher and exemplar to the young. Women were to be passive, self-effacing, generous, modest and humble. They were to sacrifice themselves to others, giving everything but asking nothing. The church promoted the woman’s role in the home as dignified and crucial rather than ornamental and subordinate. Mme Julie Riel appears to have been fastidious in her obligation to instruct the young at home. As Louis remembered his earliest years: “Family prayers, the rosary were always in my eyes and ears. And they are as much a part of my nature as the air I breathe. The calm reflective features of my mother, her eyes constantly turned towards heaven, her respect, her attention, her devotion to her religious obligations always left upon me the deepest impression of her good example.”

The women of the Riel home accepted as their inevitable lot in life a staggering burden of housework. Although not entirely self-sufficient, the family produced the bulk of what was consumed, and purchased few commercial products. It was the responsibility of the women to tend the large kitchen garden where the emphasis was on crops that could be dried, stored in the root cellar, or preserved. Métis women also collected wild fruit that could be dried or cooked into jam, as well as the sap of Manitoba maples for sugar. The kitchen stove dominated the lives of the women as a good deal of time was taken up polishing it, emptying its ashes, hauling in wood for it, and laying and tending fires. In winter the stove had to be attended to constantly. Pots used on top of the stove were of iron and these would rust without proper care, constituting another task in the daily routine. Knives also rusted, as did tinware, and vessels for cooking and storing could taint, even poison food, if not attended to. Cooking was the central ritual of housekeeping. Staples of diet were pork, deer and rabbit dishes. Duck, prairie chicken, and partridge were roasted or stewed when available. Whether from the farm, the wilds or the market, food came into the kitchen unprepared. Fowl had to be plucked, rabbits skinned, fish scaled, heavy flour sifted and raisins seeded. To transform ingredients like these into meals required many long, hot hours.

Water-related activities demanded a tremendous amount of time and labour. Water for the Riel house-hold was carried from the river, generally by horse and wagon. The Métis made canvas or leather pouches to draw water although it is likely that by 1886, buckets light but large enough for the job could be purchased. Water had to be hauled into the house for dishwashing, bathing, cooking, housecleaning and laundry, and afterwards the dirty water, cooking slops, and of course the contents of chamber pots, had to be deposited outside. The hand laundry process was a burden-some task that involved hot, heavy labour. Buckets and basins had to be hoisted to the stove, then to the washtub where the laundry was scrubbed, and wrung, and then it was lugged to the clothesline. The heat from the stove that had to be kept stoked could be intolerable in summer. In winter, snow was melted, a tedious and messy process, and the performance of hanging clothes was aggravated by the arctic temperatures. Clothes were usually hung outside to freeze, and were then brought in and strung in the main room.

Much of the clothing for the Riel family was sewn at home, and here the burden of this time-consuming task was eased by a sewing machine. Worn clothing was mended or converted to other uses. The women knitted socks, mittens, and other gear for winter. Métis women worked with hides, producing moccasins, jackets, vests, and tobacco pouches. This work was not simply a burden; these were craftswomen who took pleasure and pride in the fit of their garments, in their straight seams, uniform stitching, and in their colourful, innovative embroidery and beadwork, which often reflected both their European and native heritage. Mme Julie Riel was skilled at weaving and embroidery. While performing all of their tasks, the older women in the Riel household were instructing the younger in the various trades that defined womanhood. It is likely that the pattern of domestic life in the Riel home altered little for many years after 1886.

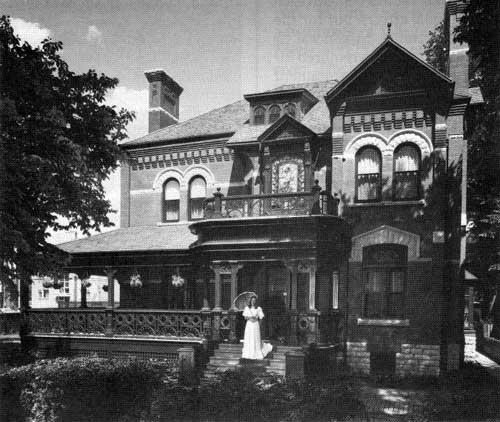

Dalnavert.

Source: Henry Kalen Ltd.

About a decade later, some miles to the north, a stately elegant home was built for the family of Sir Hugh John Macdonald, who was the son of Sir John A. Macdonald and a lawyer, Conservative politician, Premier of Manitoba, and police magistrate. It is unlikely that Macdonald was acquainted with the Riels, although the activities of Louis had some influence on the course of his life. Like a good number of young Ontarians who later made the West home, Macdonald’s first introduction to the prairies was as a member of the 1870 Wolseley expedition that arrived too late to quell the insurrection at Upper Fort Garry. In 1885 he marched to the Saskatchewan country as a member of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, where he saw action at Fish Creek, and in the pursuit of Big Bear. Macdonald was part of that influx of Anglo-Ontarians which shifted the balance of the population of the province that Riel helped found in favour of the Anglo-Saxons, and he exemplified the mentality which sought to mould the young province along the lines of Protestant Ontario. His wife, Gertrude Agnes (Vankoughnet), known as Gertie or Gay, was from a prominent Ontarian family of Loyalist stock. The children in the home were John Alexander, and Mary Isabella, known from infancy as Daisy.

The home at 61 Carlton Street was built for the Macdonalds in 1895, and it remained the family residence until the death of Hugh John in 1929. At the turn-of-the-century, this was a highly desirable neighborhood because of its proximity to the Assiniboine, its large lots, and wide streets. Winnipeg’s tendency toward residential segregation by class was by this time well in evidence. “Respectable” Winnipeggers created distinct, exclusive neighborhoods for themselves, leaving the north end to the heavy industries, the working class, and recent immigrants. The Macdonald home, described as combining features of late Victorian and Art Nouveau styles, was designed by an architect, and built by tradesmen. The exterior of the home reflected a characteristic Victorian preoccupation with appearance. It was important to display recognizable differences in a society increasingly populated by alarming numbers of “foreigners” and “aliens.” The front of the home, and the north side exhibited decorative details which enriched the external appearance, while the back service area, and the side less visible to the public, sported no adornment. Inside, the home displayed the most up-to-the-minute innovations in housing, including central hot water heating, indoor plumbing, electric lights, and walk-in closets. These were clear indications of capital and prestige. Features such as plumbing remained a luxury, and a matter of class until well into the present century. (As plumbing was a status symbol, it was certainly no shame to have the pipes visible to all, as they were in the Macdonald house, even in the parlour.) Like many Ontarians of substance who built imposing residences, the Macdonalds named their home. Often these names hearkened back to the “civilization” left behind, reflecting a desire to replicate the refined, dignified lifestyle of old Ontario. “Dalnavert” was named in honour of Hugh John’s father’s home in Toronto, and the birthplace of his maternal grand-mother near Aviemore, Scotland. The Manitoba Historical Society has restored Dalnavert to its 1895 appearance.

Source: Henry Kalen Ltd.

Dalnavert housed more than just the nuclear family, but it is clear even from the floor plan of the home that not all residents shared the same social position. A consciousness of class was evident in the desire to separate the zone housing the servants from that occupied by the family. A cook and a maid, two Irish sisters, lived in the home, and extra help, such as a butler, would be hired on occasion. Their domain was in the service, or utilitarian zone, at the back, which ensured that family members and their guests would not be disrupted or discomforted by the smells and clatter of the kitchen. This room did not exhibit the opulent decor or exotic woodwork evident elsewhere in the home. Here the servants took their meals, using the dishes and utensils designated for them which were washed and stored separately from the fine china and silverware used by the family, kept in the pantry. From the pantry the attendant at the table could serve the family and their guests yet remain out of sight. Servants had their own entrance to their zone from the outside, and to further ensure that they did not invade the privacy of the family, they had their own staircase to the upstairs, which was much narrower and steeper than the front stair, and it displayed none of the latter’s fine woodwork. The sleeping quarters of the servants were also delineated from those of the family. A door and a step down separated the small rooms at the back of the home from the more commodious chambers at the front.

The proprieties of social station were observed with guests and visitors to Dalnavert. The arrangement of the front hallway of the home manifested a need to control social interaction between the public and the family. The hall was a testing zone, or referral area, where visitors were winnowed out according to their station. An unwelcome intruder would not make it beyond the vestibule, but the more acceptable were ushered into the hall from where they could be directed to the room which suited their social station, without disturbing the privacy of any of the other rooms. Guests of the family were entertained in the parlour, or dining room, which along with the hall were the rooms most open to public scrutiny, and these were furnished and decorated to reflect the wealth and dignity of the family. Political or business acquaintances of Macdonald might be received in the study. Likely some of Lady Macdonald’s friends visited with her in the solarium. Calling was a central leisure activity of women of this milieu. The calling card tray in the hall at Dalnavert, as well as the silver card case, are reminders of this elaborate ritual which involved complex rules of etiquette. “Calling” did not always mean that one intended or expected to actually greet the hostess. In accordance with a complicated code, a woman could send any number of messages by leaving her card, or that of her husband, or both, in a certain manner. The caller might wish to convey congratulations or condolences, to maintain social relations, to expand her circle of acquaintances, or to climb the social ladder. Lady Macdonald could either receive a visitor, or instruct the servant to say that she was engaged. She might later return the call by leaving a card of her own, or express her unwillingness to acknowledge a caller by declining to do so. Calling served to codify social interaction, and it distinguished the elite from less couth Winnipeggers.

The spatial organization of Dalnavert suggests that the privacy of family members were jealously guarded. Not only were all of them separated from servants and unwelcome visitors, but in addition each family member was provided with his or her own separate place. Father had his study and mother her solarium. Upstairs, he had his own dressing room, and she her own bath room. Lady Macdonald could communicate with her servants in the kitchen from her bath room through a speaking tube which further prevented the invasion of her private world. Each of the children had a room upstairs, and infants in homes such as this had their separate nursery. (A room at Dalnavert is furnished as a nursery with toys of the late nineteenth century.) The family unit was broken down into its individual components. This was facilitated by central heating and electricity. The focus of activity no longer had to be the lamp or stove as all rooms were warm and well-lit. The family did assemble in the dining room at mealtimes where elaborate rules of etiquette guided their behaviour, and in the parlour were there was an obvious effort to foster or rekindle a sense of family intimacy. Prominent in the parlour was the fireplace, which was not a necessity in a home equipped with central heating, but it was valued for its symbolic meaning. The hearth evoked the idea of the home as a place of warmth and safety. Above the crackling fire the mirrored mantel reflected the happy scenes of a close family group. Another focus of activity in the parlour was the round table in the centre of the room which symbolized the family circle. The family bible and photograph album on the parlour table served as reminders of family history and the ties that bound them. The games and entertainments encouraged in the parlour could draw the family together. They could play and sing at the piano, listen to the gramophone or play chess. Gender-distinctive parlour furniture reflected the ideal family structure. Lady’s chairs were lower than men’s and they had no arms. This allowed room for billowing skirts but also regimented the posture expected of a lady. The spoon-backed chairs afforded a space for the bustle, which exaggerated the posterior of the womanly figure. Gentlemen’s chairs were sturdier and more commanding, with high backs and arms so that the men could lean back and be comfortable. Children’s chairs were miniature versions of the adult models.

Homes such as Dalnavert were viewed as havens or sanctuaries, as places to retreat from the new urban, industrial order. Home was a place where the virtues crushed by modern life could be preserved. A nostalgia for the peaceful, pastoral world of the countryside is evident at Dalnavert. Here an effort was made to regain the loss of fellowship with nature, and preserve the best of traditional values. The outdoors could be observed and enjoyed from the wrap-around verandah and from the front balcony. Large double doors in the parlour allowed the family and visitors to easily stroll outside along the verandah. Plants were prominent in the home, particularly in the solarium, where a deep window was designed for just such a purpose. The window was equipped with a tile floor sloping toward a drain to accommodate dripping water. In the solarium the beauties of nature, complete with a canary in a cage, were brought indoors to be appreciated year-round. Family members could bask in the restorative, reviving power of nature, even in the midst of a busy city that was thought to enfeeble morally and physically. Themes from nature were dominant in the wallpaper, stained glass, art work, carpeting, and needle-work in the home, particularly in the rooms most directly associated with women.

The woman of the house was responsible for tending and nurturing that realm, and for educating and rehabilitating those people who sought sanctuary there from the outside, sullied world. Her job was to create an environment of stability and refinement, in which the children could be educated and sheltered from the debasing world of business where greed, competition, and temptation reigned. Women were seen as a vital moral influence in society. Those people hostile to emancipation were convinced that the world’s fount of virtue and wisdom would be lost forever if women were allowed to leave their sphere and enter the professions or politics. It was believed that the industrial order destroyed human principles, ideals, and morality, and if these were to be preserved and nurtured, women had to be sequestered in the home. Women were continually assured of the importance and dignity of this work in the literature of the day. They were to fulfill their mission of motherhood and education, display piety, purity and submissiveness, and create a safe sphere of retreat from the evils of commerce.

Dalnavert offers insight into the lives of women of wealth, social standing and leisure, but it also reveals much about the lives of women toward the bottom of the social ladder, those who were in domestic service, the most common paid employment for women in Canada before 1900. It is likely more than chance that the cook and the maid in the Macdonald household were Irish sisters. Domestic service was a low-status occupation that the native-born tended to shun, and its ranks were filled disproportionately by recent immigrants. In the midst of a strange city, domestic service offered a home with a “respectable” family. Irish-born women formed the largest group within the foreign-born servant class in nineteenth century America. The Irish had arrived totally impoverished, with many women among them. “Bridget” and her sisters were stock characters in cartoons, comic plays, and serious discussions of the servant problem.

The nature of domestic work, and of the mistress-servant relationship varied considerably from household to household. The work was not defined and systematic; duties were generally agreed upon verbally, rather than through a written contract. Ambiguities and uncertainties over hours, wages and living conditions were invariably subject to the interpretation of the employer. The mistress-servant relationship was unique, and highly personalized, as the whole person was hired, not just her labour, and the worker as well as the work were under scrutiny. Many employers adopted a maternal, benevolent role in which the servant was seen as a person in need of supervision and education, but class still profoundly separated mistress and maid. The servants’ uniforms distinguished them from the rest of society, and confirmed their low social standing. The servants had little freedom to pursue an independent life. They might have one afternoon or evening off per week. They could only rarely entertain their own family and friends, and had little opportunity to join women’s clubs, or attend classes, and they certainly could not marry, have children and expect to retain a position. Employers had almost total control over the servants’ environment, in which there was little to distract them from the interests and needs of the family they served. “Thy Will Be Done,” the framed injunction adorning the wall in the cook’s bedroom, operated on more than one level.

Maintaining Dalnavert must have involved an enormous amount of housework. The servants likely worked within a system or schedule designed to promote order and efficiency. Days, and certain hours in the days were allotted to specific tasks. The maid’s weekly cycle would entail a day for washing, a day for ironing, a day for major housecleaning and so on. It might be assumed that the innovations of central heating, indoor plumbing and electricity would have served to lighten the load of work, and to a certain extent this was true. For example water did not have to be hauled for dishwashing, cleaning, bathing and laundry, and the distasteful tasks that revolved around chamber pots were mercifully unnecessary. Washing machines simplified laundry. But with technical innovations expectations increased, as standards of cleanliness rose. A fresh tablecloth could be produced daily, even in some cases for every meal. In a house with a supply of hot water there was no reason why floors and walls could not be immaculate. Personal standards of hygiene rose as people could now choose to bathe and change their clothing more often. Words such as “sanitate,” “disinfect,” and “deodorize,” all of which began to creep into the advertising of this period were indicators of the new standards. Domestic servants of this period then did not encounter a diminishing burden of tasks and responsibilities. Despite the innovations associated with it, the industrial revolution had not yet revolutionized housework at Dalnavert, where most tasks were still accomplished by traditional handpower, with minimal mechanical assistance. While some chores may have disappeared, new jobs were substituted, largely because of rising expectations.

The material culture of the domestic environment has much to contribute to our understanding of the history of women in Manitoba. Residential spaces, furnishings, decor, and common household items are evidence of the customs and ideals of life in the domestic setting, and they serve as historical evidence of the role and work of women, people who left little written record of their daily lives. At Riel House and Dalnavert it is possible to observe the female experience in two distinct domestic environments that co-existed for a time in Manitoba. In both societies home was regarded as the sphere of the women and elaborate, powerful rationales assured women of the validity and dignity of their position. Riel House provides insight into the world of women of modest means in an age before the products of the new industrialism made much impact, while Dalnavert documents the lives of women of both the upper and lower classes in the new urban, industrial order. What is most striking in considering the two together is that although the occupants of Dalnavert would have been convinced that domestic life in their home had “progressed” as compared to life at Riel house, the former home belies a desire to return to a serene rural world imbued with family warmth and repose. Indeed in the realm of domestic life, it appears that the old order was more confident than the new. Fear of loss of “civilization,” of family values, and of communion with nature is evident in Dalnavert. This elaborate expression of capital and prestige suggests struggle to achieve control and to proclaim stability.

Page revised: 1 October 2023