| Index |

|

9.

Border Stories

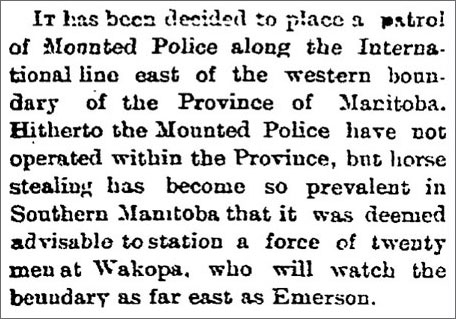

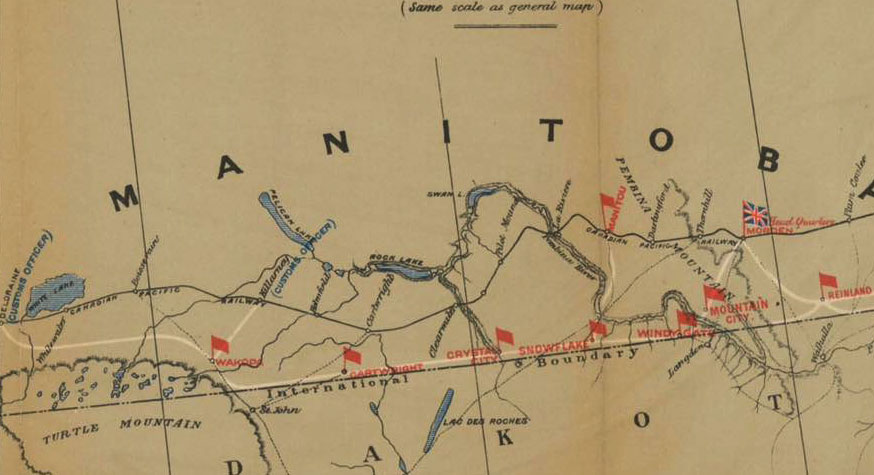

Communities that hug the border with our neighbour to the south always have some special characteristics. They may serve as points of entry with all the legal and jurisdictional issues that accompany the role. Smuggling can be an issue. Cross border crime can occur. There are therefore law enforcement issues that set them apart from other villages. On the positive side, such communities are in a position to have more of a working and social relationship with folks from across the line. The owners of a few businesses in both Wakopa and Bannerman were Americans. On the days of the fur trade, the border was just a theoretical concept. Trade and commerce was carried on without a thought for which country owned the land. It was irrelevant in that the governments of both Canada and the U.S. didn’t maintain a presence in this remote part of their respective territories. In fact, it wasn’t until the mid 1800’s that they even decided exactly where the border would be in some areas. The Boundary Commission in 1873 started the process of actually surveying the agreed upon 49th parallel that separates the western part of our two nations. In short, west of Emerson, the border was largely ignored until the land was surveyed and allotted to homesteaders. Even after the line was marked, and Ports of Entry were established, first on railway lines, then on highways, border communities on each side travelled quite freely. The border town of St. John’s ND, the site of the connection between the Brandon, Saskatchewan and Hudson’s Bay Railway and its American, Great Northern counterpart, named the trail they’ve established on the abandoned rail bed, the “Wakopa Trail”.  Law Enforcement Police services began in this area in 1885. A request for protection had been made on behalf of the settlers by the Attorney General and a detachment of North West Mounted Police was temporarily sanctioned "for the present and until a local force is formed". At that time it wasn’t the purpose of the Mounted Police provide local law enforcement. A small force was distributed at Manitou, Wakopa, Deloraine and Sourisford. In fact no cases of horse stealing occurred summer. This patrol did not return the following year.  The Nor’Wester – July 24,

1884

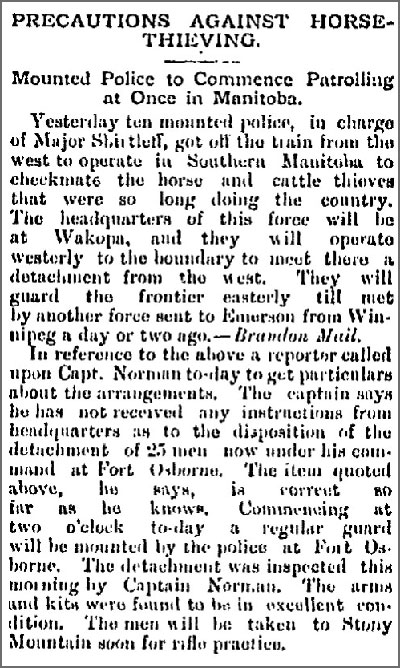

The Nor’Wester – Aug. 8, 1884 In 1888, to stop horse thieves from raiding settlers' farms, a detachment of one commissioned officer and twenty-four men was formed to patrol the border to the south from 1885 to 1890. Although these men often boarded in the villages, they had a cabin and a stable on a point of land running out from the north shore of Lake William. This was an ideal spot to check the trails through the Mountain. They effectively stopped the horse thieves and those poaching wood and timber. Several teams were seized and sold at auction. Later the detachments were stationed on trails leading from N. Dakota to Crystal City, Cartwright, Wakopa, Killarney, Holmfield, Boissevain and Deloraine. One man remained at the detachment while another was on patrol. These detachments were withdrawn in 1894 and not re-established until 1916. They were a comfort to settlers, as pioneer James Burgess reported: “One thing that I remember well was when I was herding the cattle on the prairie. I happened to look up towards the west and there coming down the trail were a lot of red coated Mounted Police on their ponies. It gave me such a scare I Soon rounded up the cattle and hurried them home.” The Metis uprising in Saskatchewan in 1885 did raise a concern. A pioneer remembers that: “Sam Kellam, Bill Barber, John Barber and another fellow by the name of McFayden were sworn in as border wardens by the R.N.W.M. Police to prevent Indians from North Dakota from joining the Riel uprising. They were paid a salary and were given powers to call anyone into service should assistance be needed. They had to report each week to the Pembina Police Detachment concerning any incidents, and were assured a quantity of Long Tom guns (British L.A. 1860 issue) with ample ammunition. The guns and ammunition were stored in La Riviere's trading post and grist mill.” The fighting was many miles away, involved only a very small group of people, and with the benefit of hindsight we know that any escalation of that conflict was unlikely. But the settlers in rural Manitoba didn’t know that. Accepted wisdom today tells us that the native populations across the west almost unanimously refused to have anything to do with the Riel uprising, and populations in the U.S. had their own battles to worry about. But local officials and media raised the “threat level.” Home Guard Companies were formed across the province. Some old timers have reported that border-area homesteaders were given Enfield rifles with bayonets on them. The “Rebellion” was over quickly, and although life in the new prairie settlements was able to return to normal, people felt vulnerable for a time. That was understandable given recent history. Our proximity to the United States had made settlers aware of events there that were much more deadly than anything experienced here in Canada. The uprising of the Dakota in Minnesota led by Little Crow in 1862 had left hundreds of settlers dead and many communities ruined. At the time, groups of Dakota Santee, most likely innocent in the matter, had settled in the Turtle Mountain area, and many were still in the region. More recently the defeat of Custer at Little Big Horn had caught everyone’s attention and some refugees from that conflict had also found their way to Manitoba. Settlers were well aware of these events.   The Nor’Wester – April 11, 1894 This report from the Daily Nor’Wester shows that by 1894, border security was becoming less of a priority. The transportation links provided by good rail links made the whole area feel less isolated. Police could be dispatched much more readily in case of any trouble. |