|

|

Part 4: On the

Factory Floor

Made in Rivers

The mandate of Sekine Canada Ltd.

was to start a Canadian made bicycle company which would operate,

subsidized by the Canadian government, for ten years, after which the

company would be on its own.

Basically it started as an assembly plant. Bicycle frames, forks,

and other parts were shipped from Japan and brought by rail to the

hangar. Parts were inspected then sent to work stations. Assembly was a

mixture of skilled labour and mechanization. For example, on the wheel

assembly line spokes were inserted into hubs which were then laced by

hand into rims. A machine then automatically tensioned the 36 spokes in

15 seconds.

Another interesting apparatus was the wheel-truing machine. It took

skill to adjust it for different rim sizes but was a marvel of

automation.

A worker had to lay a wheel into the machine where a press held the hub

in place. Within seconds the machine simultaneously used 36

screwdriver-like bits around the circumference of the rim to tighten

all the spoke nipples to a specific torque. The final truing

adjustments were done by hand.

Separate stations assembled handlebars. An assembly line moved upturned

frames along a conveyor as components were attached. Quality control

inspections were a key element of the process, before packing and

shipping was completed.

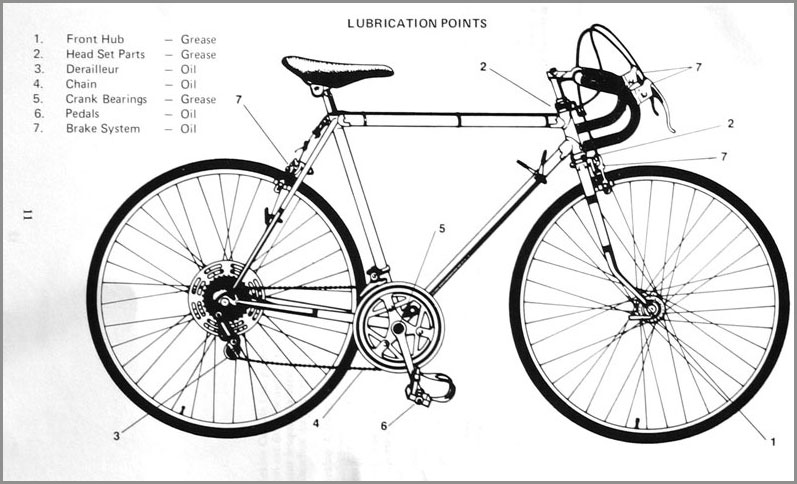

Hard at work at the Sekine Canada plant

In the beginning, they enjoyed

great success and their bikes soon became known for their excellent

quality. Frame paint was electrostatically applied, resulting in

a superior overall finish. Attention to detail and considerable

pre-assembly work made them a pleasure to assemble at retail outlets.

It was quite possible to set up a new Sekine in approximately half the

time of similar competing brands. The quality surpassed that of its

major competitor of its day, the Canadian Cycle and Motor Company

(CCM). They provided serious competition to that one time premier

bicycle manufacturer, and were often better made than many of the

bicycles being imported during the "Bike Boom" era.

Canadian made Sekine bicycles were distributed throughout North

America, with sales as far away as Hawaii and Alaska, and were readily

available in most major centers across Canada.

Bart Lavallee remembers visiting the Sekine Plant as a boy and admiring

the bikes displayed in a showcase by the entrance and remembers his dad

buying him the shiny new 10 speed. He is still in possession of a

Girl’s Sekine and say the finish is as bright as new.

A Superior

Product

That the Sekine

bicycle was known as a quality product should come as no

surprise. In the early seventies, the Japanese business machine

was focused on quality and quality assurance. Bicycles were just

one of countless excellent products being exported by Japan. It was

under the supervision of Japanese quality engineers that Canadian

Sekines were built.

This meant that the bikes were always a cut above. It was not

uncommon to hear local bicycle shop (LBS) owners comment positively on

the quality of the bicycle and its presentation when they arrived at

the shops. For example, Sekine was the only company that offered

a road bicycle with the handlebars already wrapped with handlebar

ribbon.

Each bike came with a 15 page manual with assembly, safety and

maintenance instructions.

And, forty years later, the quality built into the

bicycles still shows.

Like its competitors, Sekine targeted all levels of road bicycling

interest, from the SHA, the bottom of the line model, barely a step

above the upper end department store bicycles, to the impressive and

extremely well presented Sekine SHX.

The SHX 270 was the top of the line. It was available only by

special order and featured superior components throughout. The

SHX was the only Sekine, from the early line-up, to be offered with

tubular wheels.

SEKINE SHX 270:

The bicycle was light, sleek and

attractive, but never achieved much of

a following.

It was

designed for competition and, as such, was not a comfortable

bicycle to ride recreationally. But, as collectible

bicycles go, the Sekine SHX is one of the most desired of the Canadian

made vintage road bicycles. They are rare and well fitted

bicycles that shine with a dignity that they deserve.

The Sekine SHC 271

The more basic Sekine bike was not as special, but a quality ride all

the same.

With the appearance of the SHC and

lesser series, we see the disappearance of the exotic tube sets

featured on the more sophisticated Sekine bicycles. Gone also is

the chrome plating found on the SHT and SHS models.

Though the SHC 271 was equipped with quick release wheels, the alloy

rims were replaced by the much heavier and less effective steel

units. Other steel components added even more weight.

Despite the slightly lower quality of the materials, The SHC 271 is a

very nice recreational bicycle that offers a lively ride. It will

please all but the most demanding vintage road bicycle rider. And

once again, like all Sekine bikes, the finish and art is just great,

durable and pleasing to the eye.

The lower end models did, however,

sport a unique and often times well remembered head badge containing a

single rhinestone. Many of the people, whose interest focused on

ten speeds in the those days, fondly remember this unique badge and

often go on to comment on how good the Sekines, of their day, were.

All in all, the lower end Sekine was a well-made bicycle that could be

had for a modest price, unlike its more sophisticated brother, the SHX

that sold for $439.95 Canadian in 1976.

A Guarantee - signed by

Mishio

Kumouri, Plant Manager, remained in Canada and now lives in

Winnipeg

The

distinctive headbadge with its iconic rhinestone.

The

distinctive headbadge with its iconic rhinestone.

Some will find it interesting that after all the years that have passed

since the last Canadian Sekine rolled out of the plant at Rivers, that

one of the more prominent features remembered was a piece of costume

jewelry, glued into the Sekine headbadge,

The rhinestone

headbadge was usually fitted to early Sekines, those

manufactured prior to about 1975. After that, or some other very

close to it date, the Medialle badge came into being. Though not

a memorable as the incredibly unique rhinestone model, the Medialle

badge did, none the less, scream vintage, thanks to its ornate

appearance and cut out windows. Truly an item to help set the

Canadian Sekine apart.

Another iconic feature was the ornate Sekine rear spoke

protector…

Of course these cosmetic add-ons

were pure marketing attempts. It seems they were a success in

they remain in the minds of people nearly half a century later.

The appearance of the Canadian made Sekine changed some time after the

middle of the 1970s as did model names and the range of models offered.

Art work became simpler and most chrome plating on frame sets was

eliminated. Fork blades, on some of the higher end models, did retain

the chrome blade ends

The 1979 suggested price list ranged from $1854 to $899.

On The Factory Floor

The daily operation of the Rivers Sekine factory was unique in several

ways. The manufacturing work was carried out largely by

participants in the Lifeskills /Job Training program of the

Oo-za-We-Kwum Centre and was supervised by highly trained Japanese

engineers. Most of them resided in the former base housing almost

adjacent to the factory building. The components were made in Japan,

although there were plans to begin sourcing some part from Canadian

manufacturers.

The main focus was to take those quality parts and assemble them in a

manner that assured the consumer of a reliable, highly functional, and

attractive piece of machinery. As we have said, these bikes were about

much more than simple transportation. They were designed to inspire

pride of ownership and lasting service.

The whole process from upper management down to the factory floor

seemed ideally suited to produce the desired results.

A Sekine ad from June 10, 1974 in the Winnipeg Free

Press.

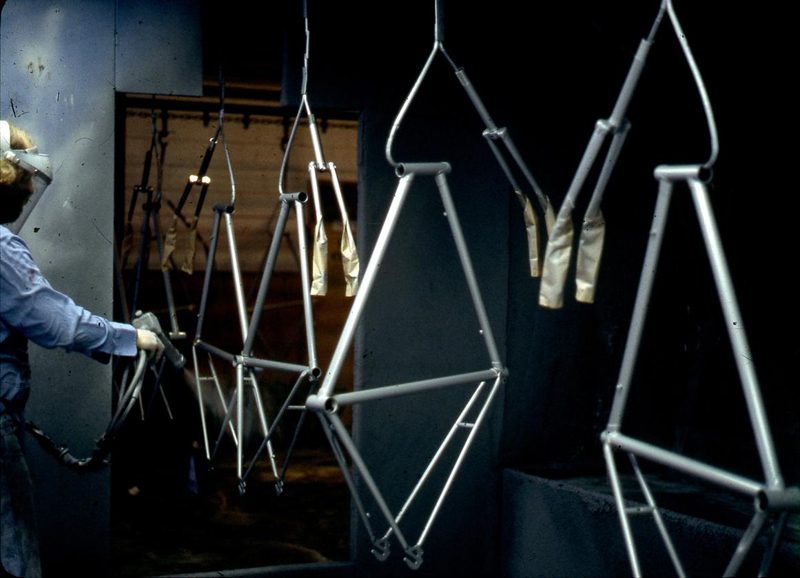

Factory Photos 1978

The following illustrate some of the factory operations that went into

producing a quality bike,

Work on the assembly line requited precision.

Applying the iconic decal.

Fork installer - Highly skilled precision work was essential at every

step.

The paint shop – vital to the appearance of the finished product and to

its longevity.

Inspection was the vital final step in each phase.

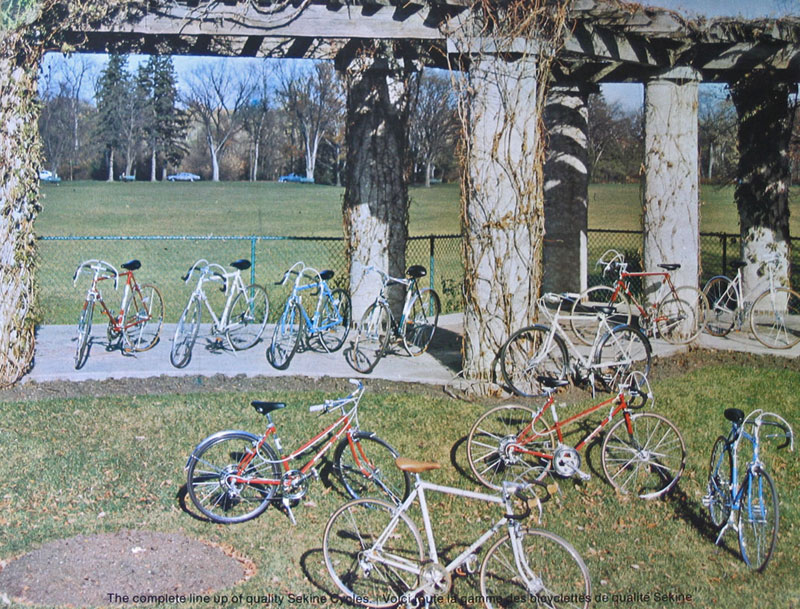

Promotional photos from the catalogue.

One of a series of promo shots in the Catalogue, likely all shot in our

region.

Life on the Factory Floor

Some Memories from Dave Cluney…

The plant was important for a number of reasons, one being that local

jobs were an asset to the community. His dad was a production Manager

at Sekine and Dave worked in the welding shop brazing bike frames.

Dave has one of only 12 Sekine 5 Speed Touring Bicycles made at the

plant. 5 went to the US 7 that remained in Canada.

These bikes were deluxe in every way. They had brake lights and

signal lights that flashed in a sequence of three bulbs, like some of

today’s cars. They came with AM radio and their own special Tire Pump

(to fit the Japanese made tubes.)

He bought it when the plant was closing, and selling off

everything. It was the last one available, displayed in the

showcase that was located on the second level of the factory.

As with all Sekines, the workmanship and materials were excellent.

He recalled an interesting incident from his first day on a job. There

were three supervisors in charge, each of whom who spoke limited

English. He was shown the work station and one manager showed him

how to adjust the torch used for brazing the tubes together to assemble

the frame. A little later the second manager came by and told him to

change the adjustment of the torch. Later still the third manger came

by and asked him to change the setting again. Finally the first manager

came back and reprimanded him for changing things.

The mixture of local workers, Aboriginal workers from other communities

and Japanese supervisors, made the operation unique and no doubt was

beneficial as a cultural exchange. More than one of the Japanese

workers, stayed in Canada and a few married girls from the nearby Sioux

Valley Reserve (Now The Sioux Valley Dakota Nation).

He remembers a man named Yamota as being the “Head Guy”.

The giant hangar that became the factory was the largest structure on

the base, built to accommodate the huge twin bladed “Vertical

Lift Helicopters ” that were used in Canada’s First Helicopter Squadron.

Another Personal Experience

Twenty six year old car mechanic, Mr. Mamiya was one of eight workers

who cam from Japan to the Oo-Za-We-Kwun Centre in July of 1973 to turn

a vacant aircraft carrier into a bicycle factory. Looking back, he

remembered that summer as “a lot of fun”. He and other workers

rented a house from among the hundreds available that used to house

military personnel.

Once the plant was operational he became the maintenance man and was

responsible for making sure that the assembly machines ran properly.

In his spare time he enjoyed summer activities such as camping and

swimming, and although he tried curling he remembers our Manitoba

winters as a time when he preferred to stay indoors.

Workplace memories included operating the electric forklift and the

difficulty encountered when one had to drill into the high-strength

concrete floor that was designed to support huge aircraft. Mr. Mamiya

and other Japanese workers left in 1979, and he took with him the

custom 1974 red Sekine SGT bike that he had brazed together himself.

The Sekine Frame Shop – 1977

For some Sekine employees in Japan, the opening of a branch plant in

Canada provided an opportunity for advancement, or perhaps an

opportunity for adventure.

In 1975 Mr. Seki, a young engineer, applied for a supervisor position

in the Rivers operation. The plant was just beginning to prepare

for expanding, and for the local manufacturing of the frames. Seki

spent a year in training in Japan before his arrival at Oo-Za-We-Kwun

in June of 1976. He took over the frame shop and was responsible for

training and supervising welders, as well as quality control and

productivity. The frame shop grew to 14 skilled employees and was

making 200- 250 frames per day.

He was very busy. It was hard work. The shop was hot and poorly

ventilated. Frame brazing releases harmful gasses. Like several

of the other Japanese workers, he stayed in Canada after the plant

closed. Mr. Seki and a few friends rented a truck and headed for

Vancouver.

Thanks to the Sekine Zine for the previous two items.

|

|