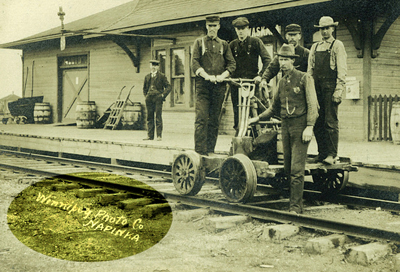

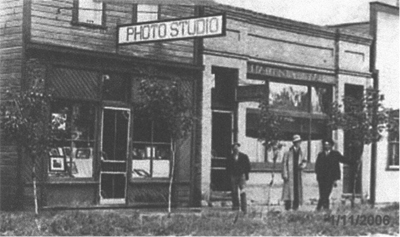

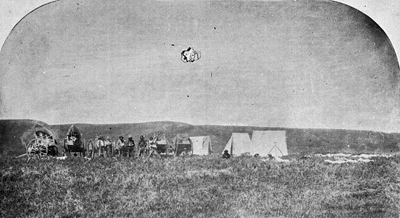

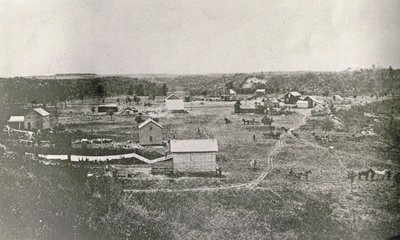

Before photography became a do-it-yourself thing most towns had a photo studio. The record they left behind is invaluable. Take a look at the inscription on this photo of the Waskada Railway Station reads, “Winnipeg Photo Co. Napinka. One finds that notation on many old photos from the region. In the early 1900’s, Napinka had a Photo Studio.  Technology has always had a tendency to eliminate jobs, when labour-saving machinery, as the term implies, reduces the need for… labour. Businesses fade away when technology gives people the tools to do previously highly specialized tasks. Once settlers got established and their basic food and shelter needs were met they went looking for less essential amenities, like family portraits. Cameras were expensive and required training, so people looked for a professional. Change started when the Kodak Brownie, an affordable and easy to use camera, was introduced in 1900. There was still a need for a professional photographer, but the business changed. Those Brownie snapshots still had to be developed. They could branch out into retail. There was still a demand for formal high quality portraits and commercial work.  The First Photographers on the Prairies The Hind Expedition  The photograph above, taken in

1859 is one of the first photos taken in

southwestern Manitoba. The photographer was Humphrey Lloyd Hime a

photographer and surveyor recruited to provide a photographic record of

an exploring expedition.

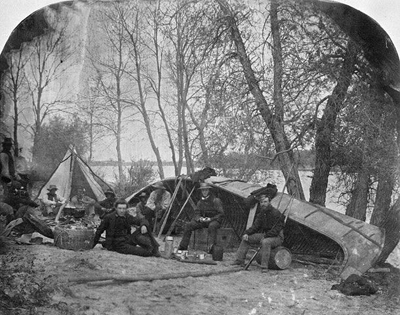

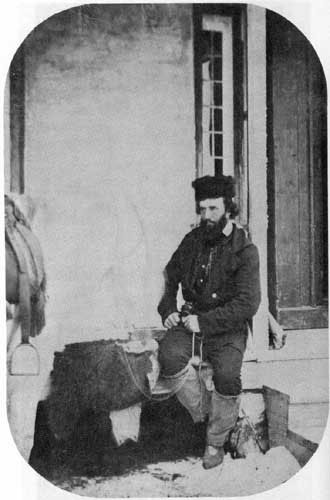

By the 1850’s the governments in both Canada and Britain were beginning to consider an important question. Was agricultural settlement viable in what was considered to be the cold and dry expanse of the western prairies? The Hudson’s Bay Company who had controlled the region for nearly 200 years, were only there for the furs, but the people in charge of the fur trade posts had already determined much earlier that "anything will grow here." But could it be grown in quantities, and efficiently enough to still be a cash crop once you factor in transportation to the market - meaning the cities of Upper and Lower Canada? The Canadian government commissioned Professor Henry Youle Hind, a Toronto geologist to explore the region in light of that question. During the summer of 1859 he and his party of thirteen men explored southwestern Manitoba. They camped at the mouth of the Souris and took the first photographs of that river. They were particularly impressed by the grasshoppers which Hind insisted took only ten minutes to destroy three pairs of woolen trousers, but they also noticed the numbers of fish rising to catch grasshoppers. They were watchful of the Sioux whom Hind called the "tigers of the plains", and they noted the beauty of the Brandon Hills. They noted the lack of timber, but found what they were looking for - fertile land. Hind’s identification of travel routes and arable land directly influenced the future of the west in terms of settlement and agriculture, and held a role in Canada’s decision to pursue the acquisition of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), albeit without regard for Indigenous peoples. Theirs was the first survey in North America from which photographs have survived. Hind contracted Humphrey Lloyd Hime to accompany him. At the time the twenty-four year old Hime was a photographer, surveyor, businessman, and financier. Now he is best remembered for his photos of the Canadian prairies. Hind’s instructions didn’t specify photographic documentation. The decision was likely his, it may have even been an afterthought as in his budget preparation records he had altered an entry for: “Mr. Hind’s Assistant - $640” to read “photographer “.  This may be the first photo (1858) ever taken of the Manitoba prairie - looking west from a point west of the Red River settlement. Photography could provide a most accurate and faithful record of places and things and copies could be taken to illustrate expedition reports. Photography was still new. It potential for his sort of work was just beginning to be considered recognized. Instead exploratory expeditions often included an artist whose sketches might be used to illustrate the official reports. In fact two artists of note: John Fleming and William Napier also provided a record of Hind’s travels. Photography was a new thing but not unheard of. Daguerreo-typists had accompanied Commodore Perry on his expedition to Japan in 1852 and the U.S. Western Survey party of 1853 employed a photographer. Leading explorers of the day were beginning to use photography extensively on expeditions. Because photography was becoming an acceptable part of life in urban Canada, its potential to record faithfully was undoubtedly brought to the attention of many Government officials. Thus, by 1858, there was a willingness to accept a reasonable expenditure for photography.  Recently Canada Post chose to highlight one of Hime’s photos. Some of Hime’s Photos  Camping at Red River  John McKay – Guide to the Hind Expedition http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/pageant/12/archivalphotos.shtml The Boundary Commission The next great set of photos with

southwestern Manitoba as the setting

are left to us thanks to the International Boundary Commission who

travelled through the region in 1873 and 1874. By this time Winnipeg

had several photographers and a record of that rapidly expanding city

and its nearby settlement was being created.

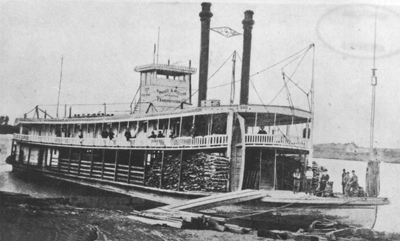

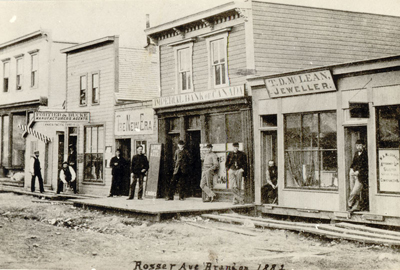

But photography still involved moving a great deal of expensive equipment. It didn’t travel well. Canada purchased Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1870 and accurately marking the border became a priority. The process began in 1872 beginning at Lake of the Woods. Her Majesty's North American Boundary Commission and the United States Northern Boundary Commission worked in cooperation from their respective sides of the border. They each had their own astronomer who calculated the location of the 49tparallel and in the event that calculations were different, the mid-point between them was accepted as being correct. With them came forty-two other members of the party, mostly from the Royal Engineers, - blacksmiths, wheelwrights, tailors, carpenters, shoemakers, four photographers, and a taxidermist. Two doctors and a veterinarian also accompanied the party. Over the course of the next two summers, the Boundary commissioners worked its way west. Their time in the southwest corner is well document in a series of high quality photos. Highlights included several shots of the Sourisford Crossing of the Souris River south of Melita, and of camps at Turtle Mountain.  The Boundary Commissioners spent three days building a bridge over the Souris River.  The Commission leaving the Long River Depot – the future site of Wakopa, southeast of Boissevain. Settlement & Photography The next photographers didn’t appear in the southwest corner until after the establishment of Brandon in 1881 and the beginning of railway service to the region. This photo of the steamer, The City of Winnipeg, was taken at Grand Valley in 1881. From 1879 until the summer of 1881 Grand Valley was the main settlement on the Assiniboine west of Portage.  The "City of Winnipeg" at Grand Valley 1n 1881. That changed when in May of that year the CPR chose a vacant parcel of land just two kilometres west of Grand Valley to be the site of a station and a divisional point. Within about a year Brandon went from being a collection of tents to being a city,  This would likely have been late in 1881, and is likely the earliest photo of Brandon.  This photo was taken near the pre-railway village of Millford in about 1882. Millford, established in 1880, was the first village west of Portage and south of the Assiniboine. It was a prominent place before Brandon existed.  This photo, likely from 1883 shows the extent of the village.  A rare photo taken in “Old” Wakopa, another pre-railroad village.  Plum Creek (later to become Souris) was another early settlement – this photo was taken around 1882.  The Land Titles Office, near where Deloraine is today, was an important stop for new settlers. Photography was new, it was

expensive, it required expertise and

equipment. So photos of southwestern Manitoba are rare from the era

before the expansion or railway service created towns and villages.

Once those villages were established and new settlers began to see some

return from all their hard work, they were quick to seek out all the

amenities available to their city counterparts. All manner of

businesses and services began to flourish in small towns. Photography

was part of that “progress”.

Sources: Manitoba Photographers, 1858 to Present http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/photographers/index.shtml Deloraine History Book Committee. Deloraine Scans a Century 1880 - 1980: Altona. Friesen Printers, 1980 |