|

One

of Hartney’s most important early industries, and arguably the one with

the greatest legacy, was brick-making. And its most important

practitioner was William Kirkland. William Kirkland (1852-1956) was

actually the third individual who developed a brick operation near

Hartney.

On the frontier of a new country, and in a place like Hartney, men like

William Kirkland were the powerful and vivid local expressions of

can-do optimisim, and of dreams made solid. They looked for the main

chance, and sometimes found it. By the few accounts we have, a man like

William Kirkland was probably determined, persuasive, dogged and proud.

And as the operator of an important brick operation be must also have

been organized, resilient, exacting, steady and patient. He was

certainly of a type, and a model of the era: a hands-on industrialist

with real skills and craftsmanship.

And from his brick operations, he was also probably rich. At the height

of his ten years of brick-making, in 1913, he was firing bricks for the

new Saskatchewan Legislative Building – at least 10 million of them.

And even discounting for such a large job (bricks usually sold for

$8/1000), and of the costs of business, it is likely that he made at

least $80,000. It was certainly enough to allow him to build a grand

house at the north end of town, with a prominent and stately view into

the community. It was, of course, of brick.

Brick

Making in Hartney

Hartney’s brick operations functioned for 20 years, between 1895 and

1913, and were key players in the local economy, providing employment,

products and helping to put the town on the map.

The three Hartney operations—Payne’s, Sackville’s and

Kirkland’s—describe the typical range of brick operations in rural and

small-town Manitoba, with the Payne and Sackville yards on the small

side and the Kirkland operation (the successor to Sackville) on the

larger side.

Hartney’s first brick-making operation, undertaken by Harry Payne,

began in 1895, just west of Hartney. Payne fired two kilns that first

year, with a final kiln of 150,000, typical for a small farm-type

operation. Payne sold some of this first stuff to W. Hopkins for his

new store, and was also shipping to many other places in southwest

Manitoba. Payne’s brick sold for $8/1000, a typical price for the

period. Payne’s reddish bricks were used in many local buildings, but

by 1902 the operation was gone, either having depleted the clay bed or

succumbing to the local competition. But even so, by the end of his

time, which lasted seven years, the operation had put out at least

3,500,000 bricks.

George Sackville opened his operation in 1898, and called it the

Hartney Brick and Delft Company. Located east of town, the operation

produced what was called a white brick (actually the buff colour we

think of). Sackville burned his first kiln in July and the last in

November of that first year, and continued for three years to ship

brick over the Northern Pacific and Manitoba Railway line to points

throughout southern Manitoba.

William Kirkland, who had worked for Sackville since 1899, took over

that yard in 1901. Kirkland`s first kiln of 80,000 bricks was burned in

May of 1902, and the lot went into the new A.E. Hill and Company

building then under construction. In May of 1905 the Star commented on

the “fine and inexhaustible deposit of clay” that was being worked by

Kirkland’s steam brick machine. A 1907-1908 Dominion Government report

on the Kirkland yard found that it sat on 15 acres and produced 30,000

bricks per day, with 10 men employed. The 1907 output was said to be

one million bricks. The operation’s last commissions came in 1913-14,

and were whoppers, with millions of bricks shipped to Regina for use in

the new Legislative Building.

Harry Payne, was also a stonemason and

carpenter.

The

Small Manitoba Brick Yard

Manitoba is geologically blessed with thousands of clay deposits,

hundreds of which have been exploited over the past 150 years for brick

manufacture. The “Golden Age” of this aspect of Manitoba’s building

history was from 1880 to 1912, the period when Hartney’s operations

flourished.

Manitoba brick operations varied greatly in size, productivity,

quality, sophistication and longevity. Research by the Province’s

Historic Resources Branch (HRB) reveals that there were about 60 major

clay sites and about 175 brick manufacturing plants that provided the

billions of bricks that were required for Manitoba’s major building

boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. That research also

reveals that William Kirkland’s was an important site, one of 12 of its

size and duration outside Winnipeg, St. Boniface and Portage la

Prairie, the major centres for brick manufacture in this province.

Information on brick manufacture in Manitoba is sketchy (the details of

industrial operations were not often covered in local newspapers) and

so it is only possible to provide a sense of typical operations based

on imaginative extrapolation of information from the HRB report.

First off, the work was hard. That probably goes without saying in the

late 1800s and early 1900s, when even with steam and horse power there

was still a large measure of manual labour. And it was long – 10 hour

days. The pay was modest, about $2/day, but it was steady, at least for

the duration of the season, usually from May (when the frost left) till

August or September.

Even small yards had up-to-date technologies, at least for the

brick-forming part of the operation. Steam-powered brick-makers often

turned out 15 to 20,000 bricks per day and therefore about 100,000 in a

week. A major physical aspect of a typical operation featured the large

covered drying sheds that new bricks were laid into.

It was the final stage of the brick-making operation that usually

distinguished a major from a minor yard: whether the brick was fired in

a scove or beehive kiln. It is almost certain that all of the Hartney

operations employed the scove kiln, a less sophisticated technology,

but one that was still effective enough to produce good quality brick.

Burnings lasted about seven to eight days, and when the outer shell of

bricks on a scove kiln was removed, workers discarded the disfigured

and discoloured bricks nearer the fire source. The remainder were set

into wagons for distribution to building sites, for transport on rail

lines, or for sale at the brickyard site.

There is nothing left of pits and operations of Hartney’s old

brickyards, not even photographs. But of course the many buildings

constructed with Hartney bricks are still here, and in each of them and

in every brick is a strong and enduring reminder of the toil, the

craftsmanship and of the very soil of Hartney, put up for the ages.

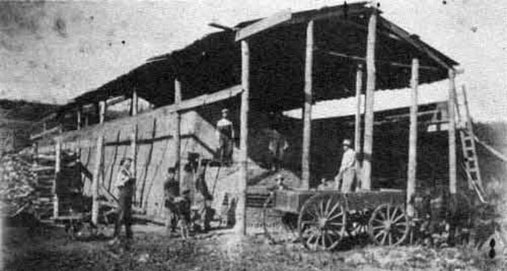

Brick drying sheds at the Wilson Brick Yard

near Gladstone, ca, 1898.

|

A typical scove kiln from the Leary Brick Yard

near Carman, 1895.

|

Beehive kilns at the La Riviere Brick Yards, one of

Manitoba’s major brick factories of the early 1900s.

|