|

THE

TEACHER IN THE HARTNEY SCHOOL with the longest tenure was Miss Blanche

Hunter, who came to the town with her family when her father bought the

Butchart hardware store in 1894. From that time until 1916 she taught

the primary room and was a profound influence for good manners and

discipline on all the grades of the school.

Blanche Hunter had a slight, erect figure of average height, and oval

face with fine eyes and beautifully arched eyebrows. She could express

approval or pleasure with a slow smile or her displeasure by a

straightening of her firm lips. Her hair was beautifully arranged high

on her head and this arrangement added dignity to her appearance. But

Blanche Hunter needed not high-piled hair to give her dignity. Dignity

was the essence of her being and it impressed her pupils while they

were in her classes, and for all their lives.

She was never an intimate friend to her pupils, but remained a sort of

deity whose approbation they strove with all their childish powers to

win, whose smile was their eagerly sought reward and whose disfavour

made their lives miserable indeed. She made learning easy and she made

her pupils feel that to be ignorant was the worst fate that could

befall them. Her approach was ever positive and sure. The large band of

Hartney folk who look back to their first school days under Miss

Hunter’s supervision are unanimous in acclaiming her a great teacher

and a powerful factor in the creation of what is fine in their lives.

Adapted from The Mere

Living, page 121.

A Day

in the Life of a Teacher

A teacher’s duties in the late 1800s and early 1900s were many, varied

and difficult. Many teachers walked a mile or more to work every

morning, and home in the evening through farmer’s fields, herds of

cows, rainstorms, or blizzards. Some had the luxury of riding horses

for lengthy distances.

Upon arrival at school, the new teacher drew pails of drinking and

washing water from the well, then set them up just inside the front

door of the school. If it was a cold morning she would gather wood from

the woodpile and start a fire. If it was hot she would see to it to

open the windows and door. She might sweep the floor and wipe off the

rough-hewn plank chairs and desks. She would check to make sure the

“privies” or outhouses were tidy and sanitary, and make sure that her

black-laquered plywood blackboard was washed.

Next, she dealt with the arrival of her students, many of them immature

and ignorant. The male students could be much larger than she, and even

older in years—and some resented being there at all, away from farm

work. There could be jeers and jibes, truancy, and general

disobedience. Many 19th-century female teachers complained that

teaching was especially hard when “big boys” flirted, teased or defied

them.

The curriculum usually included reading, writing, basic arithmetic, a

little geography and history. Books were scarce and teaching tools few.

The texts often took the form of moral tracts or primers of childish

virtues and sometimes children were even asked to bring whatever books

were at home, such as an almanac or old textbooks.

The blackboard proved essential as she printed and wrote lessons while

students copied notes onto slates. Most students had to furnish their

own supplies including writing slates and chalk. It would be some years

before scribblers and pencils came into use, and only when there was

money to buy them. In rural schoolhouses, apart from overcrowding,

practical solutions had to be sought to overcome darkness and poor

ventilation.

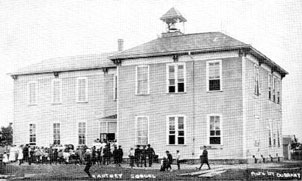

Hartney School, built in 1892 and replaced in 1954.

|