INTRODUCTION

The Inheritance: A Brief

History of

Hartney

Hartney may claim to be one of the few settlement-era railway towns

whose location was not arbitrarily chosen by the railway company.

Sometime in 1889 it became apparent that the long-anticipated Souris

Branch, that eventually was to connect Brandon with Melita and beyond,

was to become a reality. Word circulated that a town was planned on a

site somewhat northeast of present-day Hartney (35-6-23) but settlers

protested and petitioned the C.P.R., insisting that the new town should

be near where James Hartney had established a post office and store on

his farm in 1882. He had thus established a recognized centre for the

surrounding district. When the surveyors did appear they selected a

spot within a mile of the Hartney farm and, the settlers, seeing this

as, no doubt close enough, were satisfied. Upon learning that the

C.P.R had chosen the name Airdrie for the new station settlers made an

additional request that the name Hartney, already applied to the post

office serving the community, be the name of the new town. Once

again the C.P.R made the change.

James

Hartney

So, although the town was new in 1890, the region itself had a long and

interesting history. The wooded valley of the Souris has long been a

place of shelter, a gathering place for various aboriginal peoples.

Ongoing archeological explorations, especially those in the sand hills

to the west continue to uncover the buried secrets of these first

people.

In early of 1881 Samuel Long and John Fee came from Ontario to

Manitoba, and traveling south from Brandon, left the established trail

and proceeded westward into what was then unsurveyed territory. They

chose land, later identified as 32-5-23 when it was surveyed the next

summer, in the district soon known as Meglund, a few kilometres

southwest of present-day Hartney. The sod shack they erected that first

season, soon known as “The Shanty” or “The Orphan’s Home”, was to serve

as a stopping place and temporary home to a succession of newcomers in

the next two years and the nucleus of a prosperous agricultural

settlement. It was the first crucial step in the establishment of the

farming economy and social/cultural network for a district that waited

patiently for a rail link that would trigger the almost overnight

appearance of the town of Hartney.

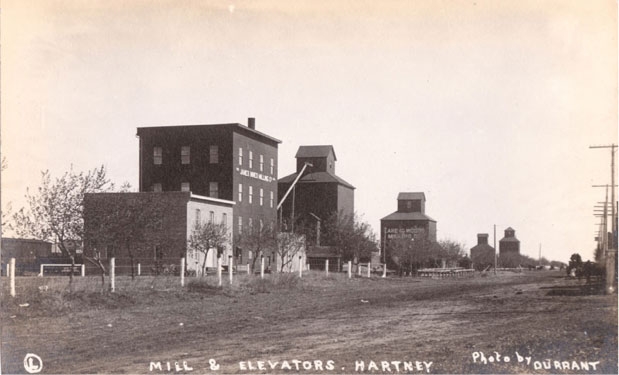

After the visit of the surveyors in 1889, the building began. When the

train whistle sounded for the first train on Christmas Day 1890, The

Lake of the Woods Milling Company had a grain elevator ready, as had

David Leckie and H. Hammond. A boarding house erected by W.H. Hotham

was in place. James Hartney and his brother-in-law S.H. Dickenson had

erected store and post office, and Dr. Frank McEown had set up a

practice and started work on a drug store.

William Hopkins had built his three-story brick building housing his

store, a residence, and a meeting hall. Seemingly overnight all the

services and goods one would expect in a thriving town were available

to settlers who had waited for the better part of a decade.

As the town grew two brickyards, a flour mill and a sash & door

factory contributed to the economy as the consolidation era was

signaled by renewed and more permanent building, often in brick and

with sometimes a more pretentious aspect. In 1902 A.E. Hill build the

two-story brick block that still stands on the corner of Poplar and

East Railway.

Along with the A.E. Hill family and James Hartney several other notable

early citizens have left their mark on Hartney. Some, like Festus

Chapin and William Callendar contributed to the commercial growth,

others like Irene Hill, Dr. Frank McEown, and Walpole Murdoch served in

other ways.

In the early years of the twentieth century Hartney consolidated its

position as a trading centre for the region while additional rail lines

created the nearby smaller villages of Underhill and Lauder.

As Hartney looks forward to the next century it has taken steps to

preserved important aspects of its past, including the expansion of the

Museum in the A.E. Hill Building. When that building and several

others recently figured prominently as sets in two movies; “The

Lookout” and “The Stone Angel” the accompanying publicity could only

help in their efforts.

The Town of Hartney has undertaken over the past few years to identify

the area’s heritage assets and to educate community members about them.

Through a rigorous inventory process, a “short list”—a collection of

the buildings and sites that most effectively sum up the town’s

history—has been identified. The buildings are an especially important

legacy, and a handful of them still clearly express the various

distinct forms, materials and details that are reminders of those early

days. Many of the selected buildings are the best remaining

representative of a common type, selected because of high physical

integrity. Each reminds us through its physicality of the very origins

of this special place. Copies of the inventory and shortlist, called

“Special Places”, are available at the town office.

A Resource for Owners

This handbook is intended to function as a guide for owners who value

the character of Hartney, and who want their building to be part of

that. Making historically‐sensitive decisions about a building is often

no more difficult or expensive than taking action that will compromise

its heritage character and that of the streetscape. The goal with the

handbook is to help provide some understanding of what makes a house or

commercial property special as part of a unique community of buildings,

and to impart information that helps to keep it that way.

Relatively little is known about the construction history of Hartney

buildings. However, with its heritage site inventory, the town has made

an excellent start at identifying types of resdiences and commercial

buildings and of tracing their origins.

Much of the work that may need to be done in the course of regular

maintenance or repair can be undertaken by almost any reasonably handy

person with a basic set of tools. As well, a vast amount of information

about historic building conservation and maintenance is available in

books, magazines and on the internet (see the resources listed at the

end of this guide as a start). Some of the available information is

highly technical advice suitable for working on museum‐quality

buildings – overkill for most ordinary buildings that are still in use.

Nonetheless, documents such as the Standards and Guidelines for the

Conservation of Historic Places in Canada, (created under the Historic

Places Program and easily found online by searching the title, or

available on CD from Manitoba’s Historic Resources Branch) can help to

explain the issues surrounding the conservation of heritage buildings,

and will have many useful hints for any building work. Following are a

few definitions of often‐used terms (paraphrased from those available

in the Standards and Guidelines) which may be helpful in considering

how these ideas might apply to your building.

Although you may think of your building as having only personal value,

chances are it has heritage value that is enjoyed by the wider

community. Heritage value may be defined as aesthetic, historic,

scientific, cultural, social or spiritual importance or significance

for past, present or future generations. The value is embodied in the

character‐defining elements of a historic place: its forms, location,

spatial configuration, uses and cultural associations or meanings.

Think about what the character‐defining elements are for your building;

in a relatively‐cohesive community such as Hartney, many will be common

to most buildings.

What characteristics does your building share with its neighbours that

make it a part of a whole? Perhaps there is something different or

special about it – maybe an unusual floor plan, rooms relatively

unchanged from when it was built, or extra detailing. These

character‐defining elements are the features you should particularly

preserve if you want to protect your property’s and your

neighbourhood’s heritage value.

Conservation

The processes aimed at preserving heritage value can be grouped

together under the heading of conservation: all actions or processes

aimed at safeguarding the character‐defining elements of a cultural

resource so as to retain its heritage value and extend its physical

life. This starts with maintenance, which you are presumably practicing

already. For building conservation purposes, maintenance is described

as routine, cyclical, non‐ destructive actions necessary to slow

deterioration. It includes periodic inspection, routine cleaning, minor

repair and refinishing, and replacement of damaged or deteriorated

materials that are not practical to save. During regular maintenance,

it is a good idea to keep in mind your building’s character‐defining

elements; often just a little more time or effort can save a historic

detail for a building owner who knows it is worth preserving.

Beyond routine maintenance, there are three major categories of

treatment: preservation, rehabilitation, and restoration. Restoration

is generally kept for museum‐quality buildings, and entails returning

the appearance of a site to match its original appearance or another

specific moment (often referred to as its period of significance). Few

homeowners would be interested in taking this approach; indeed, it

could involve stripping away layers of history that potentially form

part of the heritage value of a cottage. More useful for our purposes

are preservation – protecting, maintaining, and/or stabilizing the

existing materials, form, and integrity of a historic place while

protecting its heritage value – and rehabilitation – making possible a

continuing or compatible contemporary use of a historic place through

repair, alterations, and/or additions, while protecting its heritage

value. In each case, any work is done with continual reference to the

character‐defining elements. Rehabilitation is often the approach to

take with a building that is in very poor repair or is no longer

functional for some other reason (e.g. its original purpose is

obsolete). Depending on the state of the building, preservation could

closely resemble maintenance and repair carried out with an eye to

heritage value, while rehabilitation might involve bigger changes such

as adding a carefully‐designed, historically‐sensitive addition.

Generally, you should think about

whether the changes you are making are reversible, or whether you may

be destroying forever some aspect of your building that you or your

descendants may come to regret. The history of your community and maybe

even your family is written in the walls of your building. Always

document your work with photographs taken before, during and after the

process.

Priorities

In general, heritage professionals worldwide agree that work on

historic buildings should be undertaken according to the following

order:

1. Repair rather than replace character‐defining elements. It is better

to retain original materials and forms wherever possible. They are not

only authentic, but there is an excellent chance that they are of a

quality or workmanship that is no longer available (e.g. old growth

wood, which is close‐grained and much longer lasting than the

plantation‐grown wood we can buy today).

2. If you must replace character‐defining elements, do so “in kind”.

That is, if the original is truly beyond saving, but sufficient

physical evidence exists, copy it using the same materials, forms and

details.

3. If replacement in kind is impossible owing to insufficient physical

evidence for a copy, make your replacement compatible with the

character of the building, basing the form, details and materials on

similar cottages in the district.

Following is a guide to historically‐sensitive care for each aspect of

your building, with helpful hints based specifically on the types of

issues that Hartney building owners owners are likely to experience.

Each section is illustrated with photographs and sometimes drawings,

showing typical local examples to help you understand how your building

fits in.

Always exercise caution when making any kind of major change; remember

that any building is a system of components that interact with one

another, and changing one aspect can have negative repercussions on

others. Make sure you consider the consequences of any changes you

undertake, and plan ahead to avoid or deal with them. The more you

understand your building – its character and its mechanics – the better

you can preserve its value for generations to come.

A Reference Guide

and

Tools

for Conservation

Purpose of Design Guidelines

These Design Guidelines are primarily for local government, building

owners, tenants and business owners. Other interested parties may

include builders, tradespeople, and volunteers.

This document will help the community better understand characteristics

that have cultural, historical and architectural significance, which

when considered holistically, give character to the community as a

whole. Good design decisions can follow from this understanding.

Understanding leads to better maintenance and conservation decisions

over the long haul.

Design guidelines are not meant to be prescriptive; rather, they are

meant as a description of good design choices.

The Town of Hartney Heritage website (www.hartneyheritage.ca) has

information about local heritage resources and activities, and links to

other sites of interest.

Manitoba’s Historic Resources Branch hosts several useful publications

for heritage building owners, including the branch’s Maintenance

Manual, Windows Guide and Green Guide. The site also links to other

publications such as the Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation

of Historic Places in Canada.

Check the website of “Canada’s Historic Places” (www.historicplaces.ca)

to learn about the range of historic sites in Canada.

The Heritage Canada Foundation is an advocacy organization whose

mission is to encourage Canadians to “protect and promote their built,

historic and cultural heritage.” You can browse the HCF website:

(www.heritagecanada.org) to find many useful articles about building

conservation that have appeared in its magazine, Heritage.

|

|

|