Jesse Chester was born at Merrickville, Ont., on Nov.

17, 1829. In the fall of 1881, his water-power mill burned to the

ground and he decided to move west. In the spring of 1882, he started

out with his son, William, and came to Emerson, and from there,

jour¬neyed by horse to the present site of Baldur. Jesse had walked all

through the southwest of Baldur district and after encountering wet

marshy land, he came to the present creek. He waded north across the

creek and sat down on a boulder. Looking over the creek towards the

present town site, he said to himself, "This is where I will settle!"

and homesteaded 14-5-14. In August, 1882, his (second) wife

Sybil, and their children joined him.

Jesse and Sybil lived on their farm until the railroad began to come

through in the fall of 1889. The workers often went there for meals and

farm produce and per¬suaded Jesse to build a boarding house close to

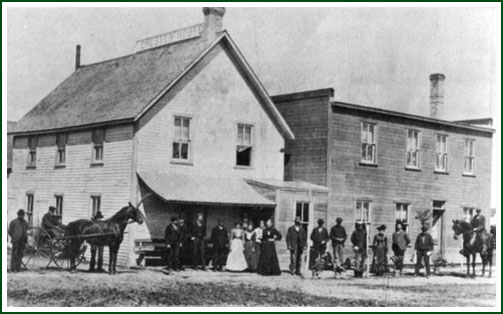

the road, for they assured him a town would soon spring up. In 1890,

Jesse built the Chester House, later known as the Baldur Hotel. He also

built a livery barn to run in conjunction with it.

The Chesters seemed to prosper and many a day the folk would see Jesse

driving his favourite mare 'Maggie C" hitched to a single-driver sulky,

up and down the country roads.

Sybil Chester is remembered as the first teacher, in the first school

established near Baldur. The school was Tiger Hills School, built in

1883, located about four kilometre southwest of the what would

become the village of Baldur.

Mrs. Chester died in May 1909, in the boarding house. In 1910, when

Jesse Sr. became very ill, he was taken in by his son, Jesse Jr. and

Nellie. He died there in May of 1910. So ended the story of a true

pioneer.

Adapted from Come into our Heritage, page

333.

The “Chester House”

From the Baldur Gazette Sept. 1899:

“Mr. J. Chester, proprietor of the Chester House, Baldur, in connection

with which he runs an up-to-date Livery stable, ten good drivers being

constant¬ly on the road; and also deals in flour, bran, shorts and

oatmeal with which his warerooms are kept well stocked, came to this

country in 1882 from Lanark county, Ontario, and was the pioneer

settler in 5-14, engaging in farming half a mile west of the present

town. Mr. Chester was instrumental in selec¬ting the present site of

Baldur, after the advent of the railroad in 1889. Considerable delay

was experienced as the railroad officials projected the site for the

town three miles west of where it now stands, this Mr. Chester fought

as the land was unsuitable in every re¬spect; he was successful in so

far that the engineer was sent out with instruc-tions to survey a piece

of land in front of which is now the farm of Mr. Brown, one mile west

of Baldur. Mr. Chester was told to get the town as far west from the

original site as possible. He consequently induced the engineer to

sur¬vey the present site, hauled his survey¬ing outfit to the ground.

Happily at last the location of the town was an accomplished fact, Mr.

Chester immediately announced the erection of a boarding house and

stables, which he has enlarged and increased to their present ample

proportions. Mr. Chester is a townsman heart and soul and every¬thing

tending to the advancement of its interests has his substantial

cooperation. By his genial manner, energy and activity in business he

has reached his present position of emolument and affluence.”

The Livery Stable

The livery stable was a vital business in any community, and in

Baldur there were several. It was at the stable where horse teams and

wagons were for hire, as well as buggies, carriages and saddle horses.

Most livery stables also allowed privately-owned horses to be boarded

there for a short time. . Horses were boarded by the day, week or month

and cared for by experienced hostlers.

Stables were also sources of hay, grain, coal and wood. The

downside of a livery stable was the smell, especially on a main

street. That is an interesting aspect of heritage conservation thatthe

typical smells of a town at the turn of the 20th century,

specially with all the horses, cannot be fathomed.

The Chester House

A Day in the Life of a Small Town Hotel

“Running a small-town Manitoba hotel in the early 1900s was hard work.

The hotel staff usually consisted of at least two chambermaids and a

cook who worked from morning till night, cleaning the guest rooms,

doing the laundry, and washing dishes. The maid's work day usually

started at 6:00 a.m. and ended at 9:00 p.m. for which she was paid $10

per month, plus room and board. Porters not only assisted hotel guests

with their luggage; they also washed dishes, milked the cows that

supplied the milk for the hotel and did all the odd jobs. The upstairs

maid also polished the silver and glassware and kept everything

shining.

All members of the hotel owner’s family had to share in the work of

running the hotel. “One of the duties of the kids was to help with the

housekeeping and at noon you had to take your turn at washing the

dishes before going back to school. My sister, Irma, served as a

waitress in the dining room when she was barely taller than the table

tops.” “The years in the Hotel were busy ones for all of the family. It

was the boys’ job to fire the wood-burning furnace. This meant rising

about three a.m. and again at six to stoke the furnace. … We were

responsible for bringing in blocks of ice and snow to melt for the

daily wash. … We hauled our drinking water from the town well.”

Wash days – usually Mondays – were an ordeal, especially in winter.

Washing bedding and clothes was often a two-day proposition. Water had

to be hauled and then heated in tubs the night before. Start-up time

was set for five or six a.m. and the laundry process quite often ran

into the afternoon. The next day, one of the maids would run the

clothes and sheets through a mangle, a machine used to wring water out

of wet laundry. Most hotels did not get running water until the 1940s

or 1950s, so water had to be hauled from a well in the summer. In the

winter, hotels used melted ice and snow, or water that had been

collected in rain barrels during the previous summer.”

© Joan Champ, 2011

|