Origins:

The Dream

and the Journey

Icelandic Society – A Brief History

Although Irish Monks may have settled briefly in Iceland prior to the

first visit by Norse raiders, it was Vikings, specifically renegade

Chieftains, who established a lasting settlement.

They had known about the island for some time. A Viking sailor named

Naddooddur happened upon it while lost, and a Swede named Gardar

Svavarsson circumnavigated it about 1860.

The first attempt to settle was by a Norwegian named Floki Vilgeroason.

He landed in the northwest but a severe winter killed his domestic

animals and he sailed back to Norway.

It’s no surprise that he named it Iceland.

Beginning in 874 many settlers came to Iceland from Norway and the

Viking colonies in the British Isles. A Norwegian named Ingolfur

Arnarson led them, bringing along with his family, slaves and animals.

By 930 the Chieftains had established a form of governance, the

Althing, essentially the world’s first parliament.

Iceland was independent throughout this period, a time known as the

“Old Commonwealth”. Its historians began to document their story in

books they called “Sagas of Icelanders”

During the 12th century conditions on Iceland deteriorated. Overgrazing

and the destruction of the forests led to soil erosion. Lack of wood to

build ships left the Icelanders dependent on Norwegian merchants. At

that time wool, animal hides, horses and falcons were exported from

Iceland. Timber, honey and malt for brewing were imported. Some

Icelanders began to look to the king of Norway to protect trade.

Feuding between clans also contributed to the decline. Icelanders who

desperately wanted peace eventually realized the only way to obtain it

was to submit to the Norwegian king.

In 1280 a new constitution was drawn up. The Althing continued to meet

but its decisions had to be ratified by the Norwegian king. Furthermore

the king appointed a governor and 12 local sheriffs to rule.

In 1397, with the unification of Norway and Denmark, Iceland fell under

Danish control.

The 14th and early 15th centuries were also troubled years for Iceland.

In the early 14th century the climate grew colder. Then in 1402-03 the

Black Death struck Iceland and the population was devastated.

Conditions improved in the 15th century. At that time there was a big

demand in Europe for Icelandic cod and Iceland grew rich on the fishing

industry.

In the 17th & 18th a strict Danish-Icelandic Trade Monopoly hurt

Iceland’s economy. The poverty of its people was further aggravated by

a series of natural disasters (especially a particularly destructive

volcano in 1783) that resulted in a population decline.

An independence movement resulted in the restoration of the Althing in

1843.

Home Rule was established in 1904, but it wasn’t until after World War

I that full independence was gained.

These are the events and forces that shaped the lives of Icelanders up

until the time of extensive migration to the “New World”.

In 1870 many groups began exploring options for re-settlement in North

America.

The Last Straw

Askja erupted again in 1961 – but the minor eruption lasted only a few

days.

This disaster was additional incentive for the migration of twenty

percent of Iceland’s population to North America. Winnipeg became the

most popular destination during the 1880s. To this day, Manitoba

remains North America’s centre for Icelandic culture and activities.

The localities of Gimli, New Iceland, Riverton, Lundar, Morden,

Lakeview, Erickson, Baldur, Arborg, and Glenboro are known for their

Icelandic cultural influence.

New Iceland

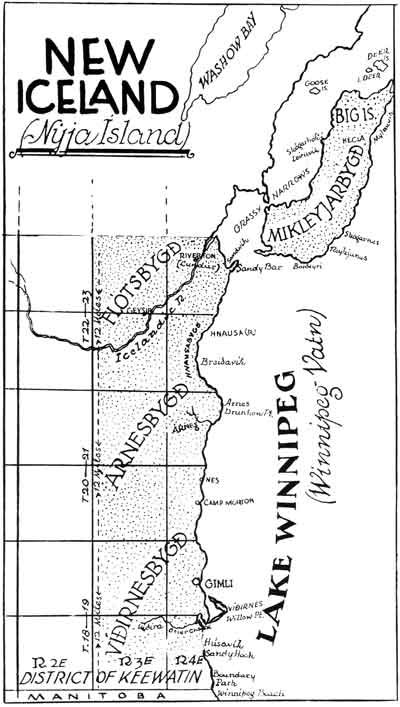

Sigtryggur Jonasson, father of New Iceland

Colony.

Sigtryggur Jonasson, father of New Iceland

Colony.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

One group

of Icleanders settled in Kinmount, Ont., in 1872 but they

found that conditions there were unsuitable and decided to keep

looking. In October of 1875, Sigtryggur Jonasson, with the assistance

of John Taylor, a missionary who was to become a lifelong friend to the

Icelanders, moved the settlers a spot along the shore of Lake Winnipeg.

Here they established the "State of New Iceland" with its own

constitution, laws and government, although in all except local

matters, it remained under the authority of the Canadian Government.

The form of self-government was modeled on the Althing back home.

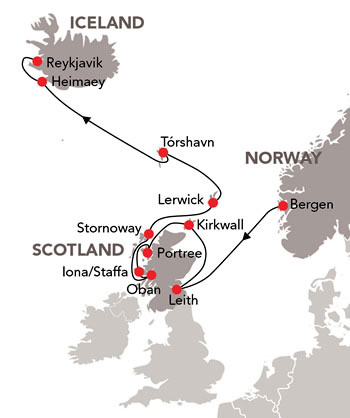

The Vatnsthing (‘Lake Parliament’) ruled over four districts:

• Vidinesbygd (‘Willow Point Community’, now the

Gimli District);

• Arnesbygd (‘Arnes Community’);

• Fljotsbygd (‘Icelandic River Community’, now the

Riverton District); and

• Mikleyjarbygd (‘Big Island Community’, now Hecla

Island).

An 1877 map showing the New

Iceland settlement

on the

western shore of Lake Winnipeg.

Source:

Archives of Manitoba

New

Iceland represents an important episode in the early settlement of

the Canadian West. The arrangement made with the Canadian Government

enabled them to preserve their language and cultural identity while

quickly becoming a valued and respected Canadians. Numerous descendants

maintain vibrant traditions and close ties with Iceland.

John

Taylor, missionary and Canadian agent for the New Iceland Colony,

no date.

John

Taylor, missionary and Canadian agent for the New Iceland Colony,

no date.

Source:

Archives of Manitoba

Hard Times

But the beginnings in New Iceland were a challenge. The first winter

set in unusually early and was extremely cold; there was a scarcity of

food, warm clothing, and housing. Added to these problems, scurvy and

other diseases took their toll of life. In 1876, a smallpox epidemic

swept through the settlement and New Iceland was put under quarantine

until 1877. The next three winters were so wet that hay crops were

ruined and cattle were starving.

New

Iceland pioneers posing in front of their log cabin in the Gimli

area, no date.

Source:

Archives of Manitoba

The

Icelanders landed at this 'White Rock' located on the beach.

Willow

Island Park has been developed by the Amason brothers and the

White Rock on which the settlers symbolically landed has been polished

and raised on a foundation.

Landing at Willow Point

Willow

Island is lined with lakeside homes today.

New Beginnings in Argyle Municipality

Everett Parsonage, who had worked for John Taylor in Ontario, had

settled at Pilot Mound and wrote to his friends in New Iceland,

encouraging them to come west and settle. In August of 1880, Sigurdur

Kristofersson and Kristjan Jonsson set out to visit their friend.

Parsonage guided them in a northwesterly direction to an area where

there were as yet, no settlers except two men, A.A. Esplin and G.J.

Parry, who were living in a tent. Sigurdur and Kristjan were impressed

with the land - much of it in rolling prairie grass with small lakes

and wooded areas. It would be easy to break and there would be plenty

of hay for cattle. When Parsonage rode to the crest of the hill

overlooking the land near the present sight of Frelsis Church, he

galloped back and shouted, "I have found Paradise!"

Gentle

hills, small lakes and fine views

Gentle

hills, small lakes and fine views

In the Nelsonville land office, near where Morden was later located,

Sigurdur filed entry for the first homestead in the Icelandic

settlement of what was to be Argyle - SE 10-6-14. He named his farm

"Grund", an Icelandic word meaning grassy plain. At Nelsonville he also

bought a scythe and walked back to his homestead to put up stacks of

hay for the cattle in the spring. Parry and Esplin helped him. They

were just out from England and had no experience in putting up log

buildings. Sigurdur had some experience in this and he helped them

build a cabin.

A few weeks later Parsonage guided Sigurdur's father- in-law, William

Taylor, along with Skafti Arason to the same area where they also took

up homesteads.

Meanwhile, Fridbjorn Fridriksson and Halldor Arnason, accompanied by

several younger men, drove 30 head of cattle from new Iceland to

Parsonage's for winter feeding. This was a long and difficult task,

taking them several days just to get the cattle across the Assiniboine

River.

Parsonage gave Fridbjorn and Halldor directions to Argyle and they also

filed for homesteads. These then were the first six men to come from

New Iceland to homestead in Argyle: Sigurdur, Kristjan, William,

Skafti, Fridbjorn, and Halldor.

The following spring, on March 15,

1881, four families joined them:

‘Skajti Arason: with his wife Anna and two small children. He brought

three work oxen and one pony hitched to four sleighs. On one sleigh, he

had built out of lumber a small frame house 6' x 10'. He also had 10

cattle.

Gudmundur Nordman: came alone with two work oxen pulling two sleighs

and all his belongings.

Sigurdur Kristojersson: left his wife Caroline and two small children

in Winnipeg with friends, to come out later. He brought his belongings

in two sleighs and a few head of cattle.

Skuli Arnason: brought all his belongings in two sleighs pulled by two

oxen, and he had a few head of cattle. One sleigh was covered and he

brought his wife Sigridur and four children.

They travelled to Winnipeg, on to Portage la Prairie, then in a

southwesterly direction. After 17 days they arrived on March 31, in the

east end of the settlement near Skuli and Gudmundur's homesteads.

The last day the weather turned bitterly cold and snowy. To save the

exhausted oxen some belongings were left along the way.

When night came, they camped together at a bluff near Skuli's land. The

cattle were suffering from extreme cold and hunger. The weary settlers

camped near the shanty of two settlers, Parry and Esplin, until

April 15, Good Friday, when each went to their own land. The day was

beautiful and mild, and in a few days the snow was gone. They camped

and helped one another until their cabins were built.

A new chapter had begun.

|

|