|

|

Turtle

Mountain Mud

The Story of Manitoba’s

Only Commercially Viable Coal Mines

Introduction:

In Southwestern Manitoba, the dirty thirties were underway.

Farmers were eager to supplement their income by picking up extra work

… and brothers John and Ole Nestibo found such work digging wells.

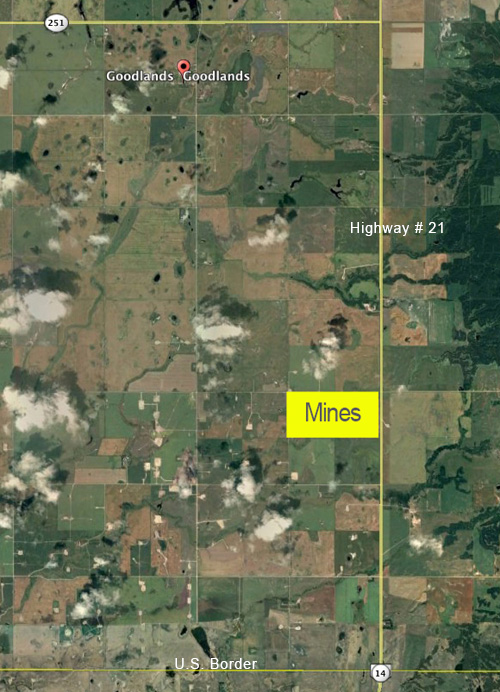

Their work took them to this ravine on the Henderson farm near the

village of Goodlands.

As John tells it…

“We were digging a well for water, it was the fall of 1931 and we were

already feeling very keenly the impact of the depression. As my brother

and I were silently digging we suddenly noticed that large chunks of

coal were being brought up by the auger. Immediately we hit upon the

idea of developing a small mine as a possible source of income. You see

… we had had no crop for two years.”

So begins the story of Manitoba’s only commercially successful coal

mines. For a decade, two mines - both the direct result of the Nesitibo

brother’s discovery - provided a boost to depression era farm incomes,

and cheaper coal for consumers.

Part

1: Early Attempts - 1880 - 1910

Part

1: Early Attempts - 1880 - 1910

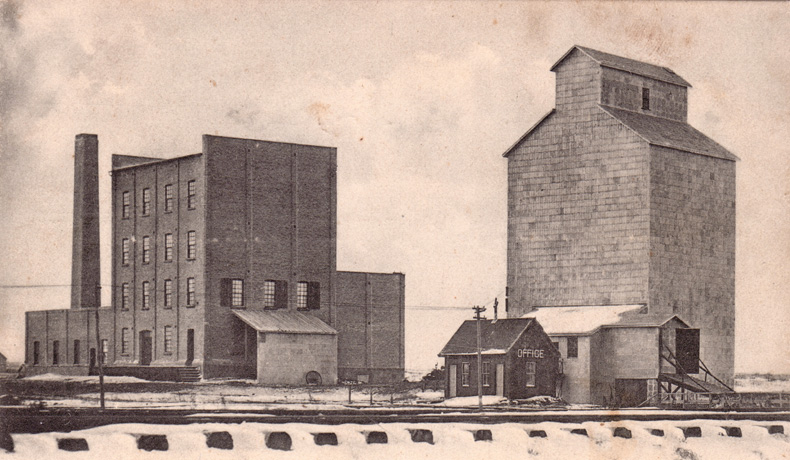

The Industrial Revolution of the 1800’s was coal fired. Coal heated the

boilers that powered the steam engines that did the work at flour

mills, like this one in Boissevain…

By the 1930’s hydro power and the gasoline engine were beginning to

change that. But coal was still important – and having a ready supply

was a real boost to a local economy. John Nestibo knew this and saw

opportunity in those black chunks he had

uncovered.

Finding coal in the Turtle Mountain region would have come as no shock.

In fact, the first discovery

of coal in the area was also the result of a well-digging operation a

few kilometres south of Boissevain in 1879. Everyone knew there

was coal there, lots of it.

But several attempts to harvest the resource met with little success.

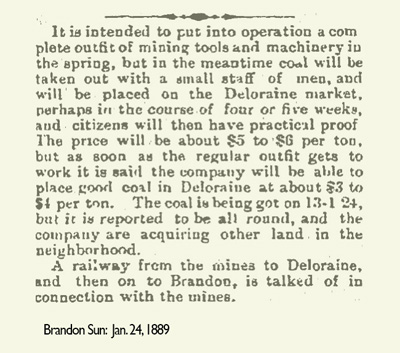

The Manitoba Coal Company in particular, made the news. In 1890 the

local and provincial press offered glowing reports. Abundant

cheap coal was just around the corner. There was even talk of building

a rail line to the site.

Did reports, such as these in the Manitoba Daily Free Press capture the

sprit of the times … or did they create the spirit?

On January 10, of 1890 they reported that it was ..

“an excellent quality of lignite coal, very hard…”.

“will supply local demands at once.”

On January 29 their reporter visited the site, and under the headline:

“Our Black Diamonds”

filed a report that was subheaded:

“Mines of the Manitoba Coal Company in operation –

Output of fifty tons

daily when Railway connection secured.”

Along with a glowing report of the region, he

concluded that,

“there is an inexhaustible supply of coal in Turtle Mountain.”

“The coal has been tested in many ways and has given entire

satisfaction.”

Other mines in that era included The Lennox Mine, the Vodon Mine, The

Manitoba Coal Company, McKay Mine, and the McArthur Mine. All were all

located on the western edge of Turtle Mountain where deep creek beds

allowed access to a coal seam.

In the twentieth century geologists confirmed what the pioneers had

suspected. There was lots of coal under Turtle Mountain

It sits in seams up to two meters thick, often separated by layers of

clay, which indicate different coal forming swamps one on top of the

other. The deposits originated about 65 million years ago, when Turtle

Mountain was a vast delta in a large sea. It was these thin layers of

geological history that attracted the attention of the first Manitoba

miners.

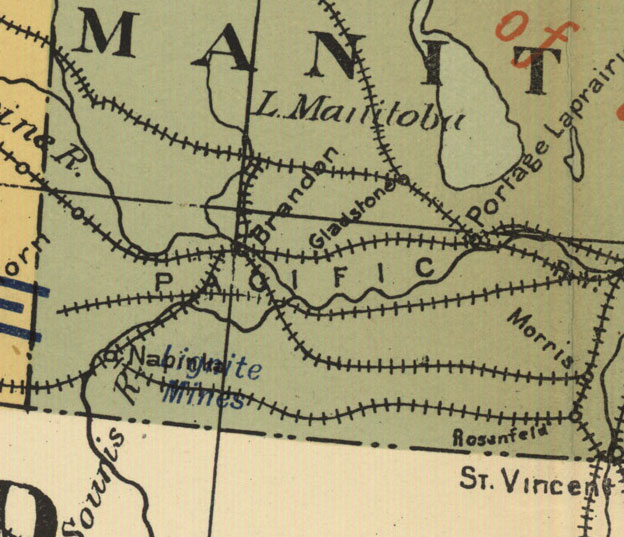

A 1900 map of Canada showing mineral deposits

noted the regions coal resources.

But there were problems from the start. The coal was damp. As one of

the local customers later recalled, “You had to wring the water out of

it before you could burn it.”

Water seepage was a big issue. This pump was used at the MacArthur Mine

to try to keep it dry.

Despite high hopes, determined effort, and considerable investment,

bringing this low grade coal out of the earth and on to market just

didn’t pay.

So the coal stayed in the ground – for a few decades longer.

Part

2: Re-Discovering the Coal the 1930’s

Part

2: Re-Discovering the Coal the 1930’s

The depression changed everything. Drought brought crop failures;

the stock market crash brought low farm prices and unemployment.

Cheaper coal would be popular, even if the locals called it Turtle

Mountain Mud.

So when the Nestibo brothers, whose descendants still farm in the

region, found what appeared to be a good supply, they quickly made a

deal with the landowner, Mr. Henderson, to start a mine.

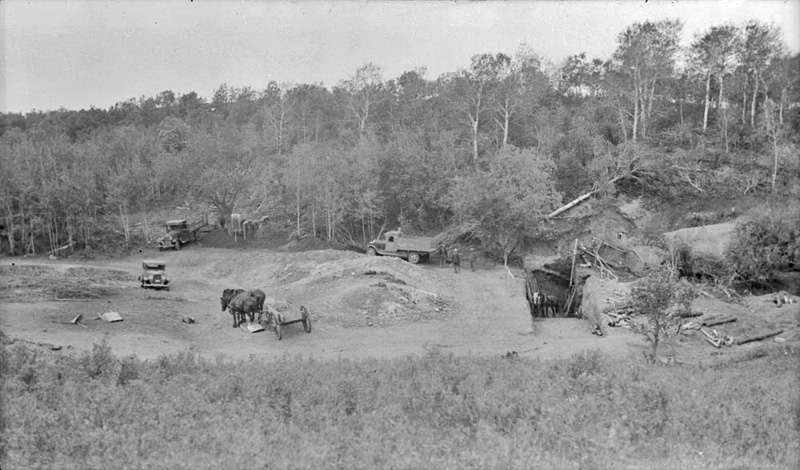

Horses and cutters were used to strip off the soil and expose the coal.

It was then picked and sorted. Within weeks 40 tons of coal were

removed and sales were being made at $2 a ton.

It was a good start with the Nestibos and Mr. Henderson splitting the

proceeds. The next year, however in a dispute over the sharing of those

proceeds, the Nestibos decided to work the same deposit for Tom Salter,

whose property sat right alongside the Henderson Mine. George

Cain took over operation on the Henderson property.

Thus, for several years, two side-by-side mines produced coal and

provided jobs for the community.

The Nestibo / Salter Mine operated during the winter from 1933 until

1938. After strip-mining procedures had taken out the most accessible

seam, two drift mines were tunnelled into the west bank of the ravine

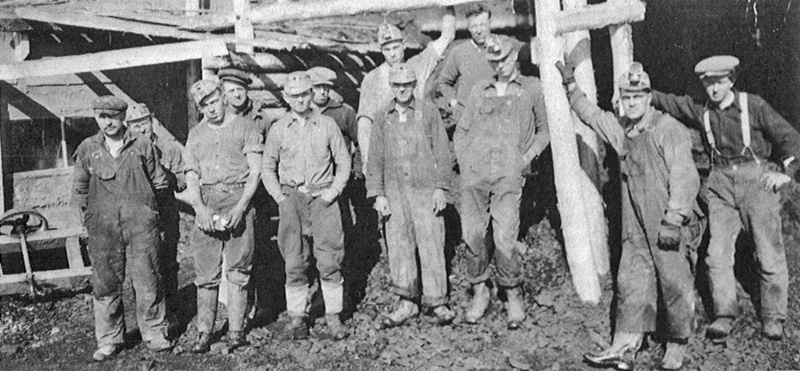

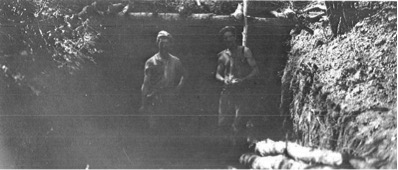

where they encountered two good seams of coal. This photo appears to be

of one of the early Nestibo drifts on the Henderson site.

Eventually a vertical shaft was sunk to 9.1 metres with three tunnels

reaching the seams.

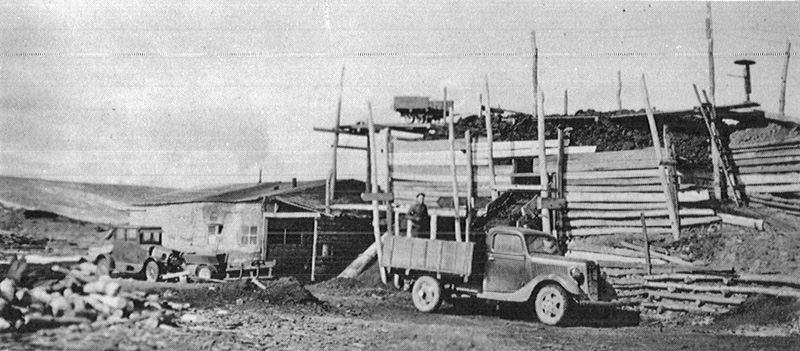

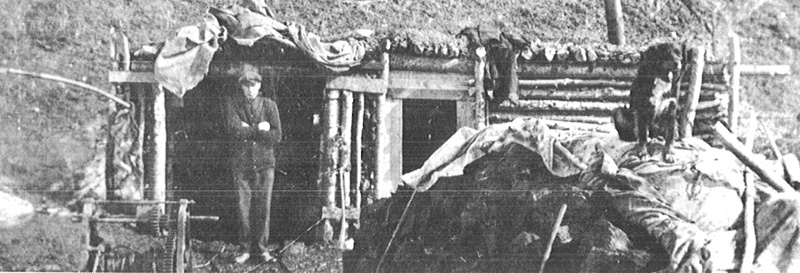

This overview shows the early stages of the Nestibo operation

The building in the foreground (with clothes hanging out to dry) was

the Nestibo Family residence. The “coal shack” was just to the left of

the house and the building with the flag on it was the dynamite shed.

The view from 2018

Over time various changes made the operation more efficient.

For example, a closed-in coal storage building with a tramway leading

from the main shaft replaced the simple loading platform.

It was a family operation. Mrs. Nestibo and Mrs. Cain did a tremendous

amount of work looking after a staff of up to forty miners – cooking,

doing laundry – generally taking care of the workers.

Their workday would start very, very early.

George Cain supervised the mine on the Henderson property on the left

side of the fence opposite John Nestibo’s Salter mine on the

right.

Part

3: Life at the Mines: The Nestibo and Cain

Operations.

Part

3: Life at the Mines: The Nestibo and Cain

Operations.

These miners are gathered near an entrance to a drift mine.

Often miners worked in pairs. The main shaft was probably high enough

to walk upright, but when you got to your own side shaft, often it was

only about four feet high. The miners worked a good part of their

day in a crouched position, on their knees with water dripping all

around them.

The temperature inside would probably be about 15 – 18 degrees

celsius. It would be very damp inside and when they would emerge

soaking wet after a strenuous sweaty shift for lunch or for dinner, the

minus 20 weather outside would be quite shock.

Coal was carried out in homemade cars using old binder wheels. The

tracks were made of 2 X 4 timbers. Nothing was purchased. It was

prairie farmers learning to be miners.

The cars were pulled up onto the loading ramp for distribution.A steam

engine provided power for the lights and the pump. It was also

hooked up to a circular saw for cutting timbers to shore up the shaft,

and used to pull cars out.

Looking back it seems remarkable that there were few major injuries.

The work was demanding. The tunnels were cramped and hastily built. And

of course – there was the regular use of dynamite. A few minor cave-ins

occurred but there was only one serious mishap when a runaway car

resulted in a broken leg.

Coal was purchased locally and marketed as far afield as Boissevain,

Brandon, and Winnipeg.

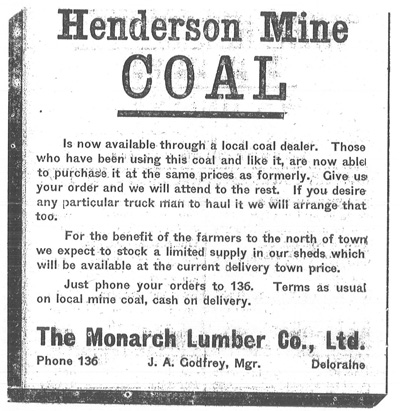

Monarch Lumber Company, which also handed product from out-of-province

producers, decided to assist the local operations by accepting their

competing product.

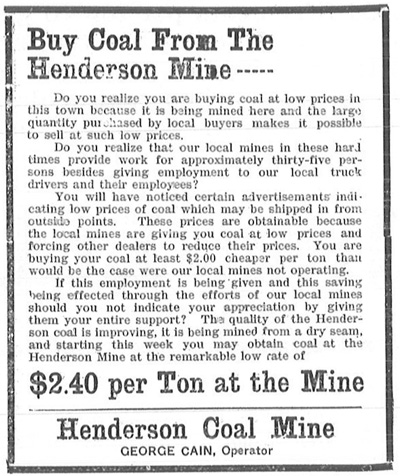

George Cain’s advertisement in several issues of the January, 1934

Deloraine Times went beyond mere promotion. It highlighted the

advantages of buying local. It pointed out that the lower price he

offered was causing a general lowering of prices, and reminded

consumers of the local employment provided by the mines and related

businesses.

Part

4: Nearby Mines

Part

4: Nearby Mines

While the Nestibo/Salter and Cain/Henderson mines were the most

successful operations, others nearby had the same idea.

Ted and Jack Williams are seen here standing at the entrance to their

Deep Ravine Mine on the McLeod farm.

Photo36

A plaque marks the location – just off of Highway 21 – at road #4

Almost next door, was the Powne Mine. A hand-driven winch in the centre

and ruins of coal car to the right were all that was left to mark the

site in the 1970’s

Here - Les Powne poses at the entrance.

The Deloraine Coal Company also operated for just a few years at this

site.

Part

5: The End of an Era

Part

5: The End of an Era

Two things happened as the 1940’s approached. The depression and the

drought both eased – bring back some of the farm income. The war also

helped boost farm prices while causing a shortage of available workers.

Just as depressed agricultural conditions started the coal rush, a

long-awaited return to agricultural prosperity sealed its fate.

This ravine, that for a brief time sheltered the two busy mines, is now

private farm land. Years ago fire destroyed the last of the structures

and all mine shafts have been closed. Little evidence remains.

Part 6: Commemoration

Times change. The prairie farmer and the small town family no longer

have much use for coal. Cleaner, more efficient, more readily available

sources of heat have come along. For decades various pieces of mining

equipment sat isolated and almost forgotten in farm fields.

Almost forgotten – but not quite.

Thanks to the efforts of A.D. Doerkson who in 1970 wrote, “The Saga of

Turtle Mountain Coal”, the story was revived. Then again in 1992, local

educator Bob Caldwell helped keep the story alive through his article,

“Manitoba’s Coal Rush” in the journal, Manitoba History. Thanks to

their efforts we have a good record of an episode of local history that

could well have been swept away by time.

Visitors to the region might happen upon the heritage display in

Deloraine Park that includes a restored version of one of the home-made

coal cars found at the site of the Hainsworth

mine.

In Winnipeg The Manitoba Museum features a display that includes a

reconstructed coal car from the Salter mine.

In recent times the Turtle Mountain – Souris Plains Heritage Assoc. has

included the story in its Vantage Points Series.

The association has also created a two-panel Interpretive Sign placed

in the village of Goodlands, the community closest to the Salter /

Henderson mines.

The years pass, and bit by bit, time erases the physical signs.

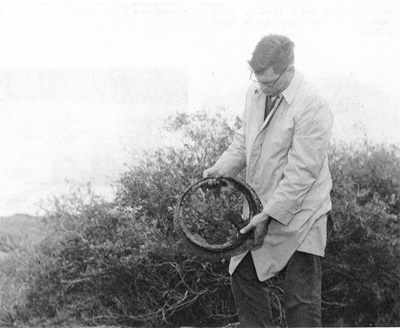

In 1970 visitors like author A.D. Doerkson might find the rusted wheel

from one of the makeshift coal cars.

The remains of a home-made scraper once used to strip away the

overburden and uncover the seam slowly disintegrates.

But while the physical signs fade the memories remain. Those old enough

to remember the day of the coal mines, do so with a sense of pride and

appreciation

|

|

|