7. Old

Millford

As

a teacher and a

student of

history, I knew a bit about Nellie McClung

and her role in the battle for Women’s suffrage. I had read at

least one

of her works of fiction, and counted myself well informed in general.

But

what I didn’t know, what my high school and university history

courses had

neglected to tell me, was that she grew up just a short distance from

my

home town. I had no idea that in the numerous times that I had

driven down

Highway #2 in the Wawnesa area I passed within sight of the school

yard

were she got her early education, within a few miles of the homestead

where

she grew up. In fact I knew distant relatives of hers, (there still are

quite

a few in the area) before I knew anything about her early life.

My point is that I think I would

have

appreciated

that information. I think

that knowing about a local concrete link to this prominent Canadian

would

have made History a bit more real for me. In fact historians were, and

still

are, somewhat careless about physical details that might establish more

of

a sense of place to the stories of the past. Manioba's definitive

popular historical record, "An Encyclopedia of Manitoba

" (an excellent volume ) lists Nellie’s childhood home,

incorrectly, as Milton.

Where did that come from? I

can't find Milton on my extensive collection Manitoba maps both modern

and historical. And to compound the insult, the older

volume, "Manitoba 125", insists that her family homesteaded

at

Manitou which was where she moved to teach school. [1] In

each case either someone didn’t check even the most

basic of sources, or an editor simply made a mental error. Either way

it

reflects a general lack of concern, a mindset in which such details are

of

little consequence. After all her life's work, the scene of her

triumphs, was far away. My friends in Wawanesa, where Nellie Mooney

married Wesley McClung in a Church that still stands overlooking the

Souris River valley, are not amused by these geographical oversights.

How could anyone not know? The lady who became known as "Our

Nell", was "Their Nell" long before she became famous. Her own memoir,

"Clearing in the West" makes it quite clear where her parents

homesteaded and is full of detail about the community where she grew up

and went to school. Ignoring those roots , or worse still, making them

up, is a denial of the whole importance of roots. And as Charlotte

Gray's biography of Nellie points out, roots are important. It is

important that Nellie moved to a pioneer farming community as a small

child. It is importnat that her parents, each in his and her own way,

were the sort of people who would make such a decision and be

successful in their endeavours. It is important that Nellie met a young

teacher named Frank Schultz, who encouraged her to question and to

think.

Place and circumstance matter if we are to understand acheivement. (And

how can circumstance not relate to place?). They also matter in

terms

of stimulating an interest in history. Thats why I

believe that such details about place are of

consequence.

I think that instead

of bemoaning the fact that interest in history seems to be declining,

we

should be examining the possibility that if we allow for an easier

connection

between the somewhat abstract facts, figures and dates, and the

physical

concrete places, buildings and artifacts, we will find that people

indeed

do like history.

I learned about the local connection to

the

Nellie

McClung story while researching,

of all things, canoe routes. In trying to learn more about the country

I

was passing though, I discovered that there were many forgotten town

sites

along the rivers and that their names were unfamiliar to me. Millford

was

one of them.

Location, Location, Location....

Provincial Road

340 used to run south from Shilo, across the Assiniboine

at the Treesbank Ferry, across the Souris over a beautiful old bridge

just

southeast of the village of Treesbank, and turn east towards

Stockton.

The road remains, although most traffic now flows across the new bridge

just

west of the ferry site, and on into Wawanesa. The ferry ceased to

operate

in the 1980’s, and there is much less traffic on the road between

Treesbank

and Stockton now. Should you happen to take that route, however,

you

will find that just after the road crosses the Souris and turns east,

it

dips through the small steep valley of Oak Creek. As you climb

back

up the other side you should see, on your right, a cairn in a small

open

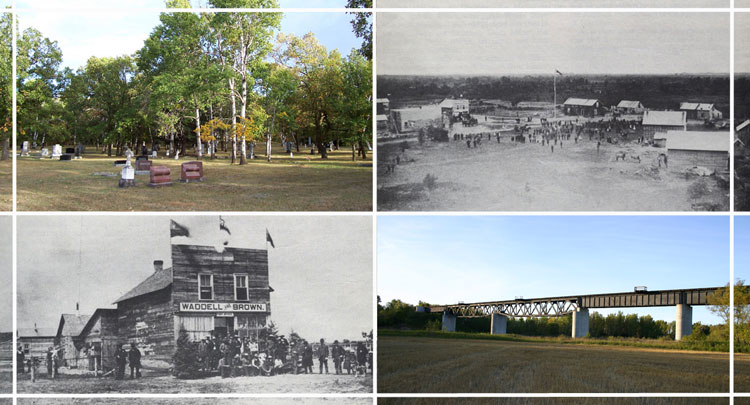

field, and a cemetery fronted by a row of mature evergreens.

As you walk through the cemetery, you will be

surprised that it is a little

larger than you had expected, and that it extends in a somewhat

haphazard

fashion back into the surrounding woods. The oldest grave there,

however,

can no longer be found today. It is that of a two year-old boy

who

died on May 3 in 1881. It was the first death in the boomtown of

Millford.

[2]

People in pioneer times must have been

more at

home with death than we are

now. It was a more regular visitor. This grave, and others that

surround

it, tell that story well. For Mr. Thomas Hall, who suffered the

loss

of a son, the fact that such deaths were common must have been no

consolation.

He had arrived in the community with the first wave of settlers in the

summer

of 1880. [3] Did he question his decision to move to this remote

territory,

and to locate in a fledgling community far from doctors and

hospitals?

We know that in moments of crisis, some did wonder if they hadn’t

made a

dreadful mistake.

Earlier that same year Letitia Mooney,

from

this

same community, as her child Lizzie lay near death with pneumonia,

cursed

the surroundings and rued the day they had left the relative security

and

comfort of their Ontario home. She had tried the usual remedies;

turpentine,

goose oil, mustard foot baths, and with the closest doctor eighty miles

away

at Portage, it seemed as though all hope was lost. Then a man

arrived

at her door having walked several miles on snowshoes, and introduced

himself

as the newly arrived Methodist Minister. He had with him some

medication

that he thought might help. He stayed three days and the child

recovered.

The minister’s name was Thomas Hall. [4]

The

Millford Site - 2001

The town was the brainchild of a

Major R.Z.

Rogers from Grafton, Ontario.

He happened to have a brother-in-law, Mr. E.C. Caddy who was to lead a

team

of Dominion Surveyors to southwestern Manitoba in 1879. He asked

him

to keep an eye out for a site for a sawmill and grist mill. His

dream

was to start a new community and to profit from the next wave of

expansion

to the west. [5]

As Mr. Caddy,

along with a

Mr. D.L.S. Huston, were supervising work in the

area near the confluence of Oak Creek with the Souris River, he was

sure

he’d found the ideal spot. After Oak Creek flows into the Souris

River it,

in turn, shortly rolls into the Assiniboine. Steamboats were

already

passing the mouth of the Souris on a regular basis, and it was a short

haul

by smaller craft to the Oak Creek forks. He sent a glowing description

of

an area bordered by three streams. [6] Rogers wasted

no time in assembling men and machinery for the establishment

of his new town. The Winnipeg Daily Times of May 6th, 1880

reported

that seven wagons and one cart were seen headed out in the direction of

the

Portage road, each of them bearing a sign: “For

Millford”. This procession

was reported to be bearing the machinery for the sawmill soon to be

constructed

at the new town site. A Mr. H. Gravely was reported to be

at

the head of the procession with Major Rodgers bringing up the rear with

his

clerk, a Mr. D. Young. The whole tone of the article was one of

optimism

and excitement. [7]

The party did in fact arrive in

the Souris

Valley by the first boat of 1880.

Major Rogers bought land and established his village. At that

time

the area was sparsely populated. William H. Donaldson, who had

come

with the survey in 1879, was living in the area and one of the survey

workers,

Will Mooney, had staked a claim a few miles to the south.

Will had come west from Ontario

after hearing,

from a variety of sources,

that it was a land of opportunity. Thomas White, after visiting

the

prairies in 1878, wrote a series of letters in the Toronto Globe

extolling

the virtues of the new land. A man named Butler had written a

book

called “The Great Lone Land” [8] on a similar theme.

Frank Burnett,

whose name appears in many of the early news reports from Millford was

inspired

to come west after reading Butlers work. [9] And more influential

perhaps,

was the account of a friend, Micheal Lowery, who came back from

Manitoba

with the oft repeated account of wild strawberries so plentiful they

stained

the oxens’ feet as they plowed. [10]

Caddy

surveyed the town

site

into 500

lots featuring a steamboat landing

and a rail line - an optimistic plan to say the least. Note that the

town

is in the “Northwest Territories “ as the Manitoba boundary

wasn’t extended

westward to its current position until 1881.

Taken

from “Historical Atlas of Manitoba.

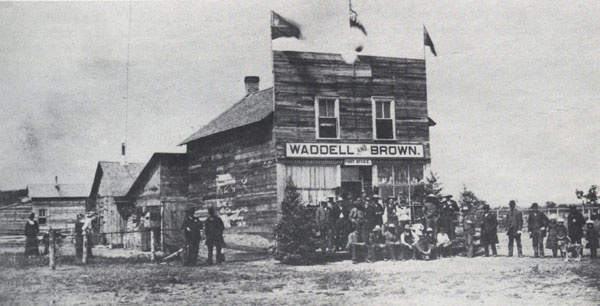

One

of three stores that were established in a short period.

(Manitoba

Archives)

Pioneers

In the winter

of 1879 Will started preparations to welcome the rest of his

family to this paradise. His parents and siblings joined him in

the

fall of 1880. His six year-old sister Helen, whom we now know as

Nellie

McLung, recalls her journey to Millford in her excellent memoir

“Clearing

in the West”. They crossed the Assiniboine a short ways above the

Souris

Mouth and her recollection captures the site perfectly: “The

Souris was a

pretty little stream with deep pools connected by an amber current that

twisted

around the sand bars.” 11]

By July of 1880 the Times

was able to report

that Millford was the “nucleus

of a rapidly extending settlement.” and that it was, “ a

striking example

of rapid, vigorous growth.” The sawmill was up and running, a

store housed

in what was referred to as a “somewhat stylish frame

building” was open and

well stocked, ferries were established and roads begun. [12]Thanks

to Nellie

we do have a very personal

look at the community and the

times, but the importance of Millford as one of the few pre-railroad

settlement

in western Manitoba has ensured that we have several other sources to

help

us reconstruct its short but vibrant existence. When the rails pushed

through

by way of Brandon in 1881 the real rush of settlers followed, but it

took

a special breed of pioneer to strike out before that time. Only a few

actual

communities existed, and most of those were to the north. Rapid City

was

by far the largest village. Grand Valley was really just a post office.

It seems a location destined

to become

“someplace”. It was at the confluence

of the two major rivers of the region. It was on pathways both ancient

and

modern. Native trails and then the path of the Metis buffalo

hunters

passed right by.

So maybe it was more than

just the promotional

efforts of Major Rodgers or

the enthusiasm of Will Mooney that drew people here. But they did come.

And

they created quite a little town, which at first drew substantial

benefit

from its location. It was a jumping off point for settlers both to the

immediate

area and to the centres springing up to the south and west at Cherry

Creek

(Boissevain) Sourisford (Melita) and Plum Creek (Souris). It was the

near

last Mair’s Landing, the last riverboat stop on the Assiniboine

before it

turned north towards Currie’s Landing and Fort Ellice. The

Mair brothers

who came in 1879 and got their start by cutting wood for the big

established

a dock and warehouse where settlers from farther west came to pick up

freight.

It is one of the very earliest named places in South Cypress. [13]

The

town site

itself offered a convenient spot for fording the Souris, and

that also drew traffic. A ferry was soon established over the

Assiniboine

about a kilometre from Souris Mouth to provide a link with Rapid City

and

the newly created city of Brandon to the north.

The industry of the

inhabitants along with the

advantageous location helped

in making Millford an important distribution centre. In reading

through

local histories and personal reminiscences one often comes across

reports

of settlers visiting the newly-formed town. They might have

arrived

there by steamboat on their way to their homesteads, or met newly

arrived

relatives; or perhaps traveled there for supplies or just for social

calls.

It was a hub of communications for the region. Travel was slow,

often

by foot or “shank’s mare” as the expression went, and

therefore even ten

mile trips could be overnight excursions. Some historians credit

Millford

with having three hotels in its heyday. While

some of these might more

accurately

be called boarding houses and/or stopping houses they were important

services. Percy Criddle, who homesteaded south of

the Assiniboine in 1882, recounts a trip to Millford in his journal

where enjoyed " a

glass of beer at the Hotel at Millford - presently came lunch to

me - excellent soup - beef steak - potatoes, turnips, pickled beets,

pie, tea- twenty-five cents - the cheapest hotel dinner I have yet

partaken

of in Canada - also I believe the best. " {13A} (p63) High praise

indeed.

Millford - gateway to Southwestern

Manitoba.

Millford - gateway to Southwestern

Manitoba.

As population

grew other lines of

communications were opened.

One of the first

settlers, Mr. Alex Reid, in a

letter dated May 9th, reported

that he was on board a steamer accompanied by a

considerable

group including Major Rogers, the town’s promoter and Mr. Caddy

who he notes

is a surveyor of considerable experience. He goes on to describe a

sheltered

valley surrounded by Oak Creek and the Souris River with views of both

the

Brandon Hills and the Tiger Hills. In another letter describes Oak

Creek,

“which never runs dry”. [14]

Alex was one of that small first wave of settlers who came on the

steamboats up the Assiniboine, or along the trail through the Spruce

Woods that fur traders had established to reach the Souris Mouth forts

and points beyond. They found ample land available that spring,

but in a letter dated that same fall he tells his grandfather in

Scotland that there was, “not a section of good land within a

radius of fifteen miles of Millford vacant.” Land was

being put under cultivation at a rapid pace. (See

More of Alex's

Letter)

There were

many surprises in store for

them. The winter temperatures

and the summer mosquitoes were two of the more unpleasant ones. Yet

seldom

in the journals and letters do you discern a note of complaint.

As

one reads their accounts of hardship you can imagine the slightly smug

look

of triumph on their faces at the telling. They took the worst

that

nature had to offer and survived. The loss of a few dozen hens to

weasels

might be a setback, but the view of the northern lights (which was

something

new to them) warranted as much comment in Nellie McClung’s

account.

Community

The town grew steadily

at first. While

the sawmill provided the rough

lumber for the first buildings, later buildings would be covered with

shiplap

brought on the steamers or hauled overland from Brandon. For a

while

there were two general stores from which one could get provisions

” at but

a moderate advance upon eastern prices” [15]

Winnpeg

Times April 23, 1881

Winnpeg

Times April 23, 1881

Manitoba

Free Press March

14, 1882

A report sent to the

Winnipeg Times at the end

of the first season by a Mr.

W.J. Sherwood on behalf of Major Rogers happily reported that:

“There are in the

village a large number

of frame buildings, with stores,

post office, blacksmith shop, and lumber, lath, and shingle

mill.” It goes

on to say that, ”Preparations have been made to have the

Assiniboine steamers

call here next year, the river being navigable from the mouth up to

this

point” [16]

A

blacksmith,

Mr. William Turnbull from Scotland, set up a forge in the town

that first year. His family was living in as tent as where many of the

other

first settlers. His was the third house built, and he acquired it only

by

threatening to leave. The Major could see that a blacksmith was a

necessity

in a would-be agricultural metropolis and obliged by making the

building

of his house a priority. [17]

Manitoba

Free Press, May 10, 1884

A warehouse (some refer to it as an elevator)

constructed by Major Rogers

near the junction of the Assiniboine and Souris met a similar

fate.

His plan to capitalize on the location and establish Millford as a

trading

centre for the region was underway quickly. His grist mill was up

and

running, and farmers were hauling their grain to him. Percy

Criddle thought his prices were a bit high compared to Brandon but

appreciated the convenience of dealing locally. [14A] He needed

storage

near the waterway but high water carried it away in 1881. He

rebuilt

and in 1882 again lost it and it’s considerable contents down the

river.

Loads of

wheat at the the

grist

mill in Millford.

Photo

from the Manitoba Archives

Loads of

wheat at the the

grist

mill in Millford.

Photo

from the Manitoba Archives

Alex was one of

that small first wave of settlers who came on the steamboats

up the Assiniboine, or along the trail through the Spruce Woods that

fur

traders had established to reach the Souris Mouth forts and points

beyond.

They found ample land available that spring, but in a letter dated that

same

fall he tells his grandfather in Scotland that there was, “not a

section

of good land within a radius of fifteen miles of Millford

vacant.” [Prev}

Land was being put under cultivation at a rapid pace.

There were many

surprises in store for them. The winter temperatures and the

summer mosquitoes were two of the more unpleasant ones. Yet seldom in

the journals and letters do you discern a note of complaint. As

one reads their accounts of hardship you can imagine the slightly smug

look of triumph on their faces at the telling. They took the

worst that nature had to offer and survived. The loss of a few

dozen hens to weasels might be a setback, but the view of the northern

lights (which was something new to them) warranted as much comment in

Nellie McClung’s account.

The town grew steadily at first. While the sawmill provided the

rough lumber for the first buildings, later buildings would be covered

with shiplap brought on the steamers or hauled overland from

Brandon. For a while there were two general stores from which one

could get provisions ” at but a moderate advance upon eastern

prices” [15]

A report sent

to the Winnipeg Times at the end of the first season by a

Mr. W.J. Sherwood on behalf of Major Rogers happily reported that:

“There

are in the village a large number

of frame buildings, with

stores, post office, blacksmith shop, and lumber, lath, and shingle

mill.” It goes on to say that, ”Preparations have been made

to have the Assiniboine steamers call here next year, the river being

navigable from the mouth up to this point” [16]

A blacksmith, Mr. William Turnbull from Scotland, set up a forge in the

town that first year. His family was living in as tent as where many of

the other first settlers. His was the third house built, and he

acquired it only by threatening to leave. The Major could see

that a blacksmith was a necessity in a would-be agricultural metropolis

and obliged by making the building of his house a priority. [17]

The settlers

were

anxious to surround themselves with the amenities of

life.

They may have been tough enough to survive a fourteen day walk from

Winnipeg

and “cold so intense it split trees wide open” and

they “cracked like

pistol shots”[18], but most of them had come from the relative

“civilization”

of Ontario. They didn’t come here to live the simple rural

life so

much as they came to better themselves. They came to make the

most

of opportunity. As soon as they could they organized themselves

for

the building and maintenance of schools and churches. They

established

Drama and Debating Societies and imported pianos and fashionable

clothes

as soon as time and money would allow. A baseball club was organized.

[19]

Congregations were established, and with time, churches were

erected.

Reverend Hall as we have noted was on the scene from the beginning

advancing

the cause of his Methodist faith. In 1882 Rev. J.S. MacKay, missionary

to

the “Millford and Souris City group of stations”, was able

to report that

“In religious sentiment Presbyterianism largely

dominates” [20]

There were some problems getting clergy, especially when times were

tough.

And article from 1884 points out that “the churches are suffering

sadly from

want of a clergyman both here (Rounthwaite) and in the Millford

district.

The cast iron rule of the Mission Board that unless a specified sum be

contributed

a clergyman cannot be provided, is not adapted to hard times.”

[21] Hard

times didn’t last forever and by 1887 the Sun was reporting on an

“annual”

Easter Monday meeting of the “English Church” at the

school house,

at which funds were being raised. [22]

One

example of

their efforts to establish a sense of community was the

Dominion

Day picnics. The first such picnic was organized in 1880 at the

very

beginning of the town’s short life and features, “baseball,

foot races leaping,

throwing the hammer, putting the stone, sack races, tog of war,

etc.”

[23] One source recalls that on Dominion Day 1881 about 200 people sat

down

to a community dinner after an afternoon of games and festivities.

McLung

remembers the 1882 picnic and credits Frank Burnett a former Montreal

stockbroker

with being the originator of the idea. She recalls boxes of

oranges

and whole bunches of bananas being brought from Rapid City. By

any

account it was a big success and even bigger things

were

planned in 1883,

with a brass band providing entertainment, and horse races and baseball

on

the agenda. The fact that they had to use a ball of yarn as a

ball

and a barrel stave as a bat didn’t dampen their enthusiasm for

this relatively

new sport. [24]

The horse race was something less of a success

however. One young man was

caught using spurs, an argument ensued which escalated into sporadic

brawling.

Apparently alcohol was involved, historians such as Pierre Berton

have suggested

that Nellie McLung’s view on the evils of drink may have been

influenced

as she watched an other wise joyous community gathering marred by the

demon

rum. [25]

Although the unhappy ending to the day’s events may not have been

a factor,

there was no Dominion Day picnic the following year.

Brandon Sun

July 17, 1884

In 1880 a Land

Office, which

also acted as a post office was established

near Millford, adding to its importance. Pioneers recount going

to

Millford to register claims, but there is some confusion as to the

exact

location. Most accounts refer to the Land Titles Office as being

just

west of the Souris near its mouth, north of where Treesbank is

now.

[26] There was a school at Souris Mouth (also called Two Rivers) for a

short

time as well, but it was located on the other side of the Assiniboine

and

a bit west. By 1882 the railway had reached Brandon, and the Land

Titles

Office was soon moved there, but Millford continued to prosper.

The fact

that several

photos

exist of

Millford in the early 1880's confirms it status as one the the

more important early settlements.

Photo

from "Manitoba Archives"

The fact

that several

photos

exist of

Millford in the early 1880's confirms it status as one the the

more important early settlements.

Photo

from "Manitoba Archives"

Most histories credit Millford as being the

first place to get mail delivery

in the southwestern corner of Manitoba, in effect, with being the first

village

south of the Assiniboine in the Westman area. Mail came via

steamboat

at first, and later over land. Millford appears on a route for

mail

delivery in an 1884 map. [27]

Like

many Manitoba towns, Millford’s rapid expansion had its birth in

speculation

and hopes regarding railway lines. It was part of the

“Manitoba Boom”

that started with Manitoba’s birth as a province and John A

MacDonald’s promise

of a national railway, but reached its apex in 1881 and 1882. In the

late

1870’s this part of Manitoba was the new frontier of a new

country.

The word had spread that the soil and climate would permit the growing

of

grain, and that presence of a rail line would make that grain readily

marketable.

Speculation fueled a rush to buy up parcels of land and promote the

establishment

of towns. Inflated claims went hand in hand with inflated prices

as

ads extolled the seemingly endless virtues of this townsite or that

farmland,

but there were also a few facts to back up some of the claims. In 1882

the

Winnipeg Daily Times reported that:

“The

largest

yield (of wheat crops) is reported at Millford, where 104 bushels

were threshed off two acres.” [28]

So while the Major had

called all the right shots as far as location and

development was concerned, it was apparent by 1882 that to create a

real

centre of commerce, a rail connection was essential. At the time

it

was the only large centre without a railway connection. It had

survived

because of its access to river transport, but in 1883 low water put an

end

to that advantage.

With that in mind

in1882 Rogers went of to Ottawa to secure a branch of the

CPR. He had all the right arguments - it seemed an ideal place

for

a rail line to cross the Souris River on it’s way to settlements

at Plum

Creek (Souris) and points west.

Railways....

When that

didn’t happen other schemes were hatched and avenues

explored.

In fact, in the 1880’s southwestern Manitoba was obsessed with

railways,

and rightly so. Having undergone the hardships of moving to this new

land,

breaking sod and planting crops, they realized that it just

wouldn’t work

without access to markets. You just couldn’t make enough money on

grain if

you had to expend all that energy and time delivering it 50 kilometres

to

the nearest elevator.

No stone was left unturned. At a

meeting held in Pilot Mound on November

of 84 representatives of southern municipalities agreed that with out a

railroad

their hopes for the future were “very bleak indeed” and

that they should

“do their utmost in every legitimate way to secure one” [29]

In 1885 the South Cypress council

authorized a $35 payment to the Secretary

Treasurer of the an entity called the Rock Lake, Souris Valley and

Brandon

Railway [30] to “defray expenses of obtaining a charter”

In August of 1886 Rogers was meeting with

local CPR official to verify that

the Southwestern Railway and the Brandon Sun was announcing that that

line

would be completed only to a point twelve miles east of Millford in

that

year. The railway officials were unable to promise days of

further

expansion and the local farmers reminded them that 50 or 60 thousand

acres

of grain needed to be marketed immediately. [31] By the

time the

branch came to Glenboro in 1886, with no immediate sign of an

extension, many townspeople felt they could wait no longer. The

grist mill had closed in 1885. The

centre with the rail line would be the advantageous place to do

business. People simply packed up and moved, often taking the

buildings with them. The village of Glenboro was virtually

started with buildings moved from Millford. An interesting note in a

Brandon Sun from 1887 under the heading “Millford

Gleanings” tells the tale:

“It is with sorrow that we learn of the death of Mr. McLean of

Glenboro, a former merchant of this place…”

[32]

A few years later this notice appears under the heading “Millford

and Two Rivers”:

“Messrs. Jackson and Gibson have sold out their store in

Millford. Mr. Jackson has taken up residence in

Glenboro…” [33]

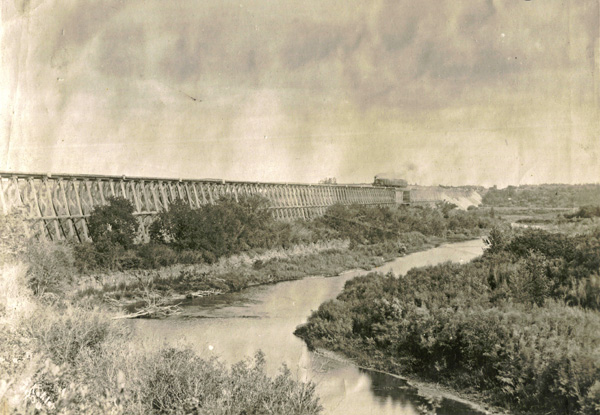

When the railway line from Glenboro was extended in 1890 it bridged the

valley on what was then the longest wooden trestle bridge in Canada,

taking it high above the near-abandonned little village.

The

Millford Rail Bridge in the 1890's

(Manitoba

Archives)

The railway line crossed the Souris just a bit to the northeast of

Millford and the new village of Treesbank (top right), was established.

It is

interesting to note that contemporary news reports offered

no banner headlines or even summary reports detailing the demise

of Millford. Aside from these telltale snippets Millford’s

passing was scarcely noted. A cynical person might suppose that the

absence of such stories reflects the relentless boosterism of the

frontier press, which had no room for such stories. More importantly,

one has to be aware that the abandonment of one site in favour of

another wasn’t seen as a negative thing, it was in fact expected.

The reports weren’t about the failure of one prospective town

site they were about the start of another. Another factor was that

towns weren’t necessarily such a big deal in rural areas.

Communities existed without towns, they were centred around rural post

offices, schools, general stores or churches, alone or in any

combination, but often without the other trademark signs of a village.

The Brandon Sun in its early days routinely included reports from such

districts, identifiable communities without the village. In this

fashion Millford continued to exist even after the buildings were gone.

Although the townsite itself all but disappeared, the community

retained it’s identity for some time. The “Millford

Cricket Club”, for example operated until at least 1906, but it

played its home games at Treesbank.

Today just up the valley wall from where the Oak Creek meets the Souris

(SW 3-8-16) there stands a new cairn inscribed with a tribute by the

area's most famous former resident, Nellie McClung.

This

reminder

and the small cemetery are all that remain of the town that once served

as a commercial centre and stopping place for an entire region. Major

Rogers abandoned his dream and moved back to Ontario. The village that

had grown to about 100 people virtually disappeared. The rail crossing

that Rogers had so eagerly sought was finally built in 1891, right were

he said it should be. It was the longest wooden trestle bridge in the

country at that time. It is still there although it was damaged by

floodwaters and rebuilt of iron.. The site is now merely an interesting

stop on a nearly deserted stretch of back road.

Sources

1.

Both volumes cited are excellent and valuable books but I believe the

mistakes reflect a lack of concern over details when those details are

seen has having only "local" interest. Nellie McLung's childhood

is an open book, literally! "Clearing in the West" details her

experiences and provides an excellent look at the local history

of the area around Millford and provides insight into the pioneer

experience in general. The errors cited are found in: The

Encyclopedia of Manitoba, Great Plains

Publications, Winnipeg MB 2007, 409: Manitoba 125,

Volume Two, Great Plains Publications, Winnipeg MB, 1994, 122. See

also: Charlotte Gray, Nellie McLung, Toronto, Viking Canada, 2008

2. McClung, Nellie, Clearing in the West, Thomas Allen, Toronto, 1935,

95,96

3. Winnipeg Daily Times, July 27, 1880

4. McClung, 79,80

5. McClung, 89

6. Glenboro and Area Historical Society, Beneath the Long Grass,

1979,

14

7. Winnipeg Daily Times, May 6, 1880

8. Butler, William Francis (Sir) 1838-1910. The great lone land: A

narrative

of travel and adventure in the north-west of America . London: Sampson

Low,

Marston, Low & Searle, 1872.

9. McLung 104

10 McLung 30-32

11. McClung, 72

12. Winnipeg Daily Times, July 8, 1880

13. Glenboro and Area Historical Society, 175-6

13A. Criddle, Alma, Criddle-De-Diddle-Ensis, 1973, 71

14. Alex Reid, Letters and Journal, Archives of Manitoba,

Microfilm Ref.

MG8 B61

14A. Criddle, Alma,

Criddle-De-Diddle-Ensis,

1973, 58

15. Winnipeg Daily Times, July 8, 1880

16. Winnipeg Daily Times Dec. 9, 1880

17. Glenboro and Area Historical Society, 16

18. These are a few of the more common descriptions found in local

histories

19. The Brandon Sun Weekly, July 27, 1884

20 Winnipeg Daily Sun, Sept. 21, 1882

21. The Brandon Sun Weekly, June 26, 1884

22. The Brandon Sun Weekly, April 28, 1887

23. Winnipeg Daily Times, July 8, 1880

24. Brandon Daily Sun Weekly, July 17, 1884

25. Berton, Pierre, Marching as to War, Canada’s Turbulent Years

1899-1953, Doubleday Canada, 2001, 103

26. A Rome, A.E. Oakland Echoes

27. Ruggles, Richard I, and Warkentin, John, Historical Atlas of

Manitoba, 406 (Post Office Map 1882)

28. Winnipeg Daily Times, Oct. 12 1882

29. The Brandon Sun Weekly, Nov.13, 1884

30. The Brandon Sun Weekly, Feb. 5, 1885

31. The Brandon Sun Weekly, May 8, and 19, 1886

32. The Brandon Sun Weekly, Oct 20, 1887

33. The Brandon Sun Weekly, March 21, 1889

|

|

|