|

1. Introduction

&

Background

The concept of False

Starts came from my first explorations of abandoned settler communities

in Southwestern Manitoba, specifically those that blossomed briefly,

when would-be farmers, most of them from Ontario, ventured west from

Winnipeg and Portage La Prairie along the Assiniboine River and

established a series of communities along that river and along the

Souris River, beginning in 1878. Those first small villages,

naturally placed along the main waterways of the southwest corner,

existed for only a few years before they were abruptly replaced with

the arrival of the railway. I thought of those villages as False

Starts, the underlying assumption being that the new towns, created to

conform to the new transportation reality, were the opposite of False

Starts – they were somehow legitimate or lasting propositions.

And they did last. Some of them. For a while.

But then things changed again. Just as those first villages, often

along rivers, gave way to new villages placed along railway lines, the

next transportation revolution, the automobile, dictated that

successful towns would be on major highways.

My impression was that the concept of False Starts was unique to the

early settlement era, and was just a matter of timing. Of course

pre-railroad villages had existed for decades elsewhere in our province

and elsewhere on the continent. It was just that settlement didn’t

reach into this corner of the province until railways were also

approaching. The short-lived pre-railroad villages in Southwestern

Manitoba didn’t get their start until the need for that sort of village

was about to disappear.

It was like buying a brand-new, state-of-the-art VCR, just before DVD’s

came on the market.

Thus in the longer view of history, all settlements, all towns, even

societies, cultures, communities, business ventures, and political

movements, can be seen as False Starts. Hindsight is more

reliable than placing a wager.

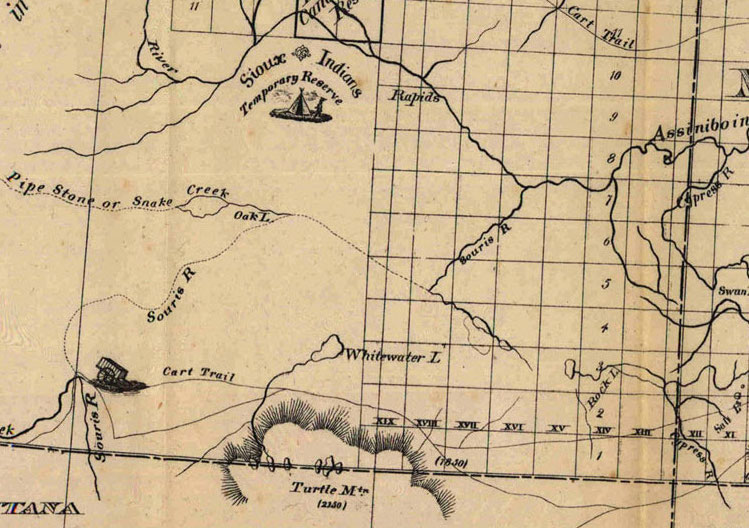

The area had been carefully explored however and this map shows many of

the region's geographic features that we know well today.

* From Laurie's 1870 map of

Western Canada

* From Laurie's 1870 map of

Western Canada

In the 1870's, Southwestern Manitoba had no established agricultural

communities. The fur trade was essentially over in the region and

former posts along the Souris River near Hartney and at Souris Mouth

had been closed for some time. The buffalo were beginning the steep

decline that would see them almost exterminated by 1880.

The so-called “settlement” of the West itself was a False Start in the

sense that at the time, and for some time, we seemed to overlook the

fact that this land was, and had been, already settled. We’re still

sorting that out, but as we proceed let’s remember that the history of

Southwestern Manitoba didn’t begin in 1878.

That’s not to say that a False Start was always a mistake. Quite the

opposite. False Starts are initiatives. They can be mistakes. Planning

a town called Moberly on the swampy southwest corner of Whitewater

Lake, and marketing it as a lakeside paradise, wasn’t wise. It wasn’t

even legal.

But most False Starts are the necessary steps in finding our way.

Explorations. Test cases.

When faced with a choice between the uncertain path and staying home,

it’s a good thing that humans forge ahead.

When William Francis Butler stepped off of the deck of the steamer

International as it prepared to dock near the forks of the Assiniboine

and Red Rivers in the fall of 1869, the frontier settlement of Winnipeg

was not yet the capital of the region and the region was not yet the

province of Manitoba. Mr. Butler was on a mission, a mission that

related to the creation of the province. He was there to meet with Riel

and get a feel for the situation. 1

That mission, a delicate one, carried out with tact and competence,

likely had little impact on the outcome of the confrontation that gave

birth to our province. But his other mission, that of exploring this

new land, had a more impact than he would have imagined. Butler wrote

an account of his travels, which he published as "The Great Lone Land",

and that book painted a picture of the west that caught peoples

imagination and inspired some of them to check it out for themselves.

Quite a few came to what we now call Western Manitoba, perhaps in a

sense, arriving before it was fully open for business. Like

gatecrashers at a concert or at a holiday sale in a big box store, they

learned patience. And a few other things.

In 1879 there were still few settlers hardy enough to leave the

security of the Red River and Lower Assiniboine valleys and push west.

That was about to change.

That region, still officially part of the Northwest Territories, was

sparsely populated at the time, but that had not always been so. The

wooded valleys of both the Assiniboine and Souris Rivers and their

tributaries had long provided wood and shelter for Nakota, Dakota and

Ojibway camps, and more recently, Metis buffalo hunters. Archaeological

expeditions are currently helping us decipher the unwritten records of

the first peoples, while written records start with the French Canadian

explorers and traders.

The Nakota (whom we called the Assiniboine) brought LaVerendrye and his

party fifty-two men from the Red River in 1738. He travelled with his

brother, two sons, one slave, twenty-one hired hands, and a group of

natives. We may chuckle a bit at the mistakes in his maps, they relied

on hearsay to fill in the parts he hadn't actually visited, but he

managed in a relatively short time to provide what was effectively a

quantum leap in terms of recorded knowledge of the area. His primary

interest was in exploration, but he needed the profits from the fur

trade to finance explorations. His business mission was to outflank the

HBC and he tolerated the time that trading took away from his real

interest. - the search for the "Western Sea".

After LaVerendrye, came the traders. They built forts in an

ever-expanding reach from the forks of the Red and Assiniboine. They

learned to live in this land, with invaluable help from the Aboriginal

people, and they learned that agriculture was possible outside of the

Red River Valley. That led to the first wave of homesteaders in the

"Manitoba Boom" of 1878-1882. These were the people who started the

process of conversion to an agriculturally based society and economy.

It is far too easy to summarize that process, as our school history

books did, as some sort of inevitable evolution - a sort of

pre-ordained progress of mankind. There was a well-orchestrated effort

to portray this “new” land as empty. It wasn't. That story is being

well told elsewhere and I won’t dwell on it here, but I will certainly

acknowledge it. Let me just say that “Truth and Reconciliation” begins

with “Truth”. We’re working on it.

What did the first European settlers find here?

Wouldn't it be nice to have more photographs or even sketches of the

landscape! The ones we do have coupled with the excellent written

accounts do help us form a picture.

First, the expression "Bald Prairie" did indeed apply. Almost all

accounts from pioneers mention the availability of wood as a matter of

importance. When riversides and other wooded places were taken, few

remaining farm sites had trees, and the hauling and sale of wood became

a source of ready employment for those with access.

Alexander Henry, while travelling across country from Brandon House to

Fort Ash in 1806, noted the great view he had from the hills after

stopping at a small lake, which must have been Lake Clementi, directly

south of Brandon. He mentions seeing where the "Rapid" River empties

into the Assiniboine. As it is a distance of some 25 km I suspect that

what he saw was the trees on the banks of those rivers, and that

because that was almost the only place trees could be found, he

correctly assumed that the river was hidden. 2

One hundred years is a short time, in the geological, and even

geographical sense. And although a comparative set of snapshots of the

same stretch of land, one dated 1880, and another dated 2020, would

reveal very real differences; those differences are the result of our

intervention on the land. We made the changes.

Henry Youle Hind's 1858

expedition, camped along the Souris River.

Henry Youle Hind's 1858

expedition, camped along the Souris River.

The photograph above, taken in

1859 is one of the first photos taken in southwestern Manitoba. The

photographer was Humphrey Lloyd Hime a photographer and surveyor

recruited to provide a photographic record of an exploring expedition.

The

trees grew because the prairie fires stopped, and because cultivation

altered the drainage. The trees, in turn, further altered drainage.

Altered drainage likely changed the nature of the rivers, and

streams. But, underneath it all, if you get away from the roads and

highways, from the population centres, from the well-tilled fields, you

will find the land much as it was.

It

was, by most accounts, harsh, yet inviting. It is difficult to get a

real picture because the accounts left are so subjective. The

impressions of the first European settlers were colored by their hopes

and dreams. They recount what to us might seem incredible hardships

with a matter-of-fact sort of shrug. One gets the feeling that they

sometimes reported only the highlights - and that they accepted from

the outset that the hardships came, literally, with the territory.

I

think that most of the “pioneers”, like the early fur traders, were so

entranced by the newness and the openness of the place that they tended

to ignore the loneliness and the harshness of the climate. They were

caught up in the excitement of their individual endeavours - leaving

the old behind, striking out towards the new. They were just too busy

and too distracted by their dreams to pay much attention to trivial

details like weather and lack of amenities. And they kept coming.

Not

all of them stayed, but many of them thrived.

By

1876 the survey was making its way westward, ahead of the first

European settlers who were to arrive at Grand Valley, just above the

Rapids noted at the top centre of this map, and at Millford, near the

junction of the Souris and Assiniboine.

Surveyor's

maps published annually between 1879 and 1882 show that the southwest

corner went from being empty - to being nearly full. Well, not quite

full - it took a few more years for the dust from the Manitoba boom to

settle. While most of the land had been claimed and/or purchased by

1882, it took another decade to separate the speculators from the

homesteaders, the buyers from the actual settlers.

The

little square sections on the map filled up. The names were shuffled.

Many newcomers found that the well-marketed campaign to attract

settlement had oversold the attractions of the new land and decided it

wasn’t for them. Some learned that farming wasn’t for

them.

Their names were replaced by the newcomers. This slowed and the

population stabilized. Many prospered.

Then

the towns sprang up as increasing income caused the need for services

to skyrocket. Many of the first towns didn't survive the transition

from the era of rapid expansion to the era of entrenchment and economic

growth. They had been situated along the first highways - the

riverbanks. And although the exact locations were chosen with an eye

towards the coming railway, that factor involved guesswork, and a good

dose of optimism. The new towns of the 1990's were based on actual rail

lines not proposed ones, and there were many of them. No one wanted to

travel far to deliver their produce, or to purchase supplies, and with

the spread of the rail lines, they didn't have to.

The

cycle of increased production leading to increased purchasing spiraled

through the first few decades of the new century, and after a sobering

interlude in the thirties, renewed its march into the early forties.

Then

the next change began. Increasingly large and mechanically

sophisticated farm machinery made it possible for one family to farm

thousands of acres. Increasing costs of production made it seem

necessary to do so. The townships (36 sections or square miles of land)

that once supported from fifty to a hundred families now were home to

fewer and fewer. Rural depopulation began. And like the spiral of

supply and demand that created the rural towns, a new, downward spiral

left buildings abandoned on every other old farm site, and empty fields

where towns once stood.

Drive

through western Manitoba, and you will see fields of wheat larger than

the entire farm I once called home. That field can be harvested in a

few hours by a combine costing more than our half- section farm was

worth. A hog barn staffed by just a few men produces more pork per

month than an entire municipality would ship to market in years. The

era of corporate agriculture began and our pioneer past has become even

more remote.

But

it would be so nice to stand on a hilltop and see the land as it was in

those days before the ox and plow were replaced by the

tractor,

and before the crooked dirt trail was replaced by the straight smooth

pavement.

Map of the Province of Manitoba

and Part of the District of Kewatin and

North West Territory (1876).

Begg,

Alexander: Ten years in Winnipeg (1879)

Bryce,

George: Holiday Rambles Between Winnipeg and Victoria (1888)

Bryce,

George: John Black, the Apostle of Red Rivber

Bryce,

George: Manitoba: Its infancy, growth, and present condition (1882)

Butler,

William Francis: The Great Lone Land

Carle,

Frank Austin: The British Northwest (1881)

D'Artigue,

Jean: Six Years in the Canadian North-West

Dawson,

McDonell: The North-West Territories and British Columbia (1881)

First

Days, Fighting Days : Women in Manitoba History

Girard,

Senate Hearings / CPR West Railway Line, 1877

Grant,

George M.: Sanford Flemings Expedition Through Canada in 1872 (1877)

Hill,

Robert Brown: Manitoba: History of itsEarly Settlement...(1890)

Hind,

Henry, Youle: North-West Territory: Reports of Progress (1859)

Macounn,

John: Manitoba & the Great Northwest

McClung,

Nellie: Clearing In The West

MacDougall,

W.B. MacDougall's Illustrated Guide, gazetteer and practical hand-book

for Manitoba and the North-West, 1882

McKenzie, Nathaniel : The men of the Hudson's Bay

Company, 1670 A.D.-1920 A.D . 1921.

|

|

|

|

|