Chapter

4: Laying the Rails

The task of

building a railway across the vast prairies was a mixed blessing.

True, the terrain

offered few obstacles, no mountains, only a few deep river valleys….

and long stretches of dry, flat, terrain. But the distances were truly

immense, and the materials all came from far to the east.

Wood was in short

supply on the prairies.

Today it might be

easy for us to forget the sheer effort required, the thousands of trees

to be felled, ties to be cut, rails to be forged; the huge amount of

material to be transported and assembled. The National Dream was in

addition to being an undertaking of incredible optimism and foresight,

an enterprise that relied heavily on brute force and manpower.

The first task

was surveying the line. Great care was taken to follow the “path of

least resistance”.

Surveyors

near

Brandon – Archives of Manitoba

The goal was to

go around hills rather than over them, and always to find the easiest

crossing of any valley or creek.

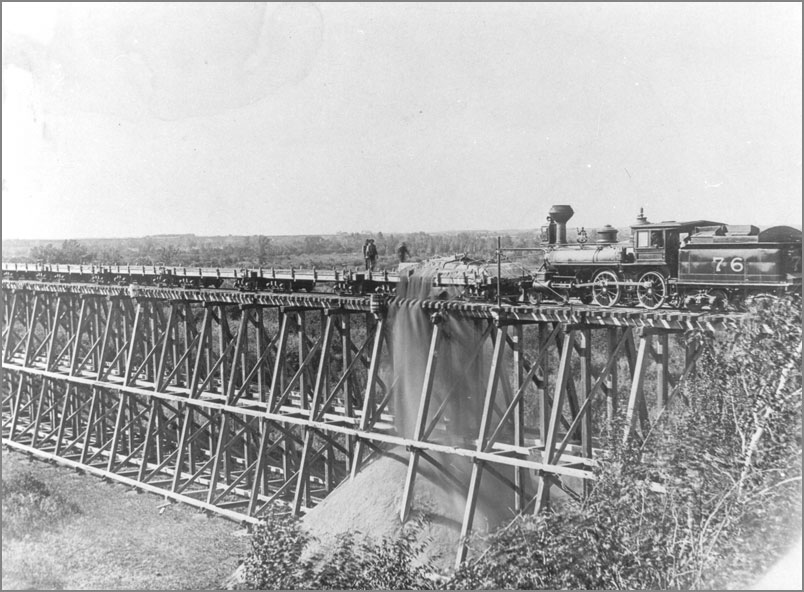

The CPR

Bridge at

Millford – Archives of Manitoba

Creeks and rivers

were crossed with wooden trestle bridges that were later filled in for

stability. One advantage of the CPR route through Westman was that it

avoided deep valleys like this crossing of the Souris River on a branch

line south of Brandon.

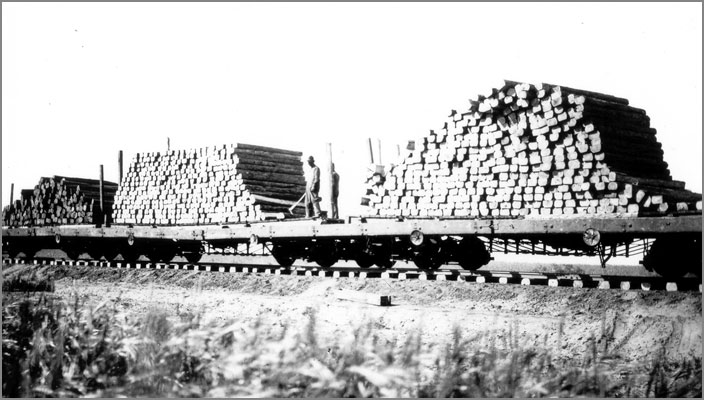

Ties – Archives

of Manitoba

A flat, level bed

was the first construction task, followed by the laying of the wooden

ties, and the attachment of the steel.

Unloading –

Archives of Manitoba

On a good day

three to five kilometres of track could be laid. Brandon pioneer

Beecham Trotter said ten kilometres was the record.

Placement –

Archives of Manitoba

Rails were

unloaded from flat cars and carried up the bank by hand, twelve men to

a rail, placed on hand cars, pushed to the end of steel and carried in

to place.

They were placed

4 feet, 8½ inched apart (standard gauge) and spiked into place.

The conditions

weren’t for everyone - turnover was high – especially as the nights

grew cold. Workers usually boarded and slept in rough two-storey

Pullman cars – with rows of bunks three deep on the upper level dining

on the main level.

In the summer of

1882, as the line pushed west from Brandon, 5000 men and 1700 teams of

horses were at work. Just three years and (1,568.2 km /973 miles) later

Van Horne, MacTavish & other officials were there at

Craigellachie, BC for the ceremonial last spike.

The construction

over the summer introduced thousands of lonely single men to the

fledgling city.

|

|