by Peter Kuch

MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1962-63 Season

|

As you may have heard, a cartoonist has little affinity for dates, historical or otherwise, but I appreciate that to a historical society, some semblance of a record must be forthcoming.

Possibly this is all that you will record officially of this treatise. If so, your evening may be a failure.

But to me, dates had little to do with the influence of Arch Dale as a cartoonist, for his brilliance in depicting the events of the early Western political scene proves to be as relevant today as it was in those days.

Arch was born in Dundee, Scotland, May 31, 1882. At the age of seventeen, he worked on the Dundee Courier, and later on the Glasgow News. He came to Canada, and homesteaded in the Touchwood Hills, Saskatchewan. In 1907, he submitted a cartoon to the Winnipeg Free Press. It was accepted, and on the strength of this, he got a job with the Grain Growers' Guide.

Then in 1910, he joined the Free Press for a short time. He then returned to Scotland for a trip, and while there, accepted a position on the Manchester Dispatch, and worked with "Poy", one of the best known cartoonists of his day with the London Evening News. He later replaced "Poy" with the Harmsworth Syndicate. He returned to Canada in 1913 to rejoin the Guide. In 1919, he married Claire Porter, and in 1921, he went to Chicago to work with the Universal Feature and Specialty Co., where he syndicated his DOO DADS. In 1927, he returned to the Free Press, and worked until his retirement twenty-seven years later. He died in the Spring of 1962, leaving behind a brilliant commentary of his times, and a daughter Julie who has carried on as an artist with the Winnipeg Free Press.

Now that facts and dates are behind us, I can proceed with the most important aspect of Archie Dale, the man. Through his reminiscences. and other sources, I feel that Archie was indeed a product of his times. His stories of the plight and working conditions of the women and children in the jute mills and coal mines around Dundee, his native city, were indescribable. His reflections of life in the slums of Glasgow of Sauchiehall Street, and the fights there on Saturday nights (so fierce that the police had to patrol there in squads for their own protection), and the poverty all around ... his reflections on these things were so grim that, years later, when someone remarked what tremendous fighters the Scots were, Archie replied, "Why not? ... they've had lots of practice."

Those early years, I feel, gave Archie Dale a deep understanding of the frailties of human nature, and a deep sympathy for the underdog. The one thing he could not tolerate was "intolerance" itself. Having made up his mind to seek greener and (hopefully) free-er fields, he decided to emigrate to Canada where two former bachelor friends had invited him to stay and homestead with them in Touchwood Hills in Saskatchewan.

I could not possibly do justice to some of the stories Archie spun of his life as a homesteader, for only he could give them the right flavour in the telling.

But one episode that I recall occurred because of typhoid due to bad water. Typhoid was rampant, and they decided to dig a well. Archie was delegated to handle the windlass while his friends took turns digging. It wasn't too easy handling buckets filled with mud, and finally, one of them overturned "accidentally" (as Arch said) over the head of the one who had been complaining over Archie's slowness. The enraged friend started up the ladder with dire threats, but Archie, with great presence of mind, spotted a small mallet and, as his friend's head appeared, Arch tapped him gently on the head, but hard enough to cause him to drop back down to the bottom where lie quickly cooled off. Fortunately, as Archie remembered, it wasn't too long after this that he received his call to come to Winnipeg. Once here, he wandered from the Grain Growers' Guide to the Winnipeg Free Press, then over to Scotland and then back to the United States.

He seemed to be conducting an endless search for success and happiness in his chosen field. At last, in 1927 (and now finally a man with a wife and daughter to look after), he settled down with the Free Press where Fate, it seemed, had finally chosen the right time and the right place for Archie Dale.

It was 1927, a year when Canada could well have been termed an affluent society. The inflationary curve was heading upward with the female skirt. Social Credit was an unfertilized germ in the mind of Major Douglas ... the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation would have been laughed out of existence. Possibly the only real fact in existence in those disaster-headed days was that Arch Dale had settled finally at the Winnipeg Free Press. This dour Scot with the whimsical pen, who didn't know a politician from a leprechaun, was launched headlong into the most exciting era of Canadian politics. Completely incapable of understanding the barest elements of personal finance Archie found himself beating ideas out of his fertile brain to prick the bubble of funny money. It was probably one of the greatest mysteries of the Winnipeg newspaper world of those days how an immigrant lad, fresh from successive disappointments, could cut through the issues of the day so clearly, and with such great force, that political greats cringed before the acid of his pen.

It must be recorded that, while Archie hit hard at many public figures, there was a kindliness and sense of humour behind his caricatures which even the victims were quick to recognize. (If I remember correctly, Aberhart was about the only figure that Arch thoroughly disliked ... and this feeling was mutual).

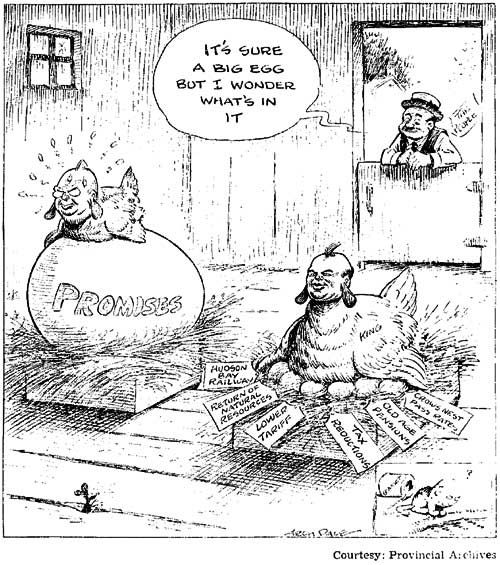

His personal favourite, I feel, was Mackenzie King ... but his favourite subject was Prime Minister Bennett, who gave him tremendous scope.

Throughout these years, Archie Dale remained totally oblivious to the mantle of fame that had descended upon him. Never once was his head turned, as the influence of his cartoons spread across the land. When his idea was safely down on the drawing board, approved by John W. Dafoe or George Ferguson, he would move off to the world he loved best around a glass-loaded table, to join pithy companions whom he held in much hisher esteem than the political pundits he caricatured.

Source: Provincial Archives of Manitoba

It was easy for Archie Dale to find an enemy in Prime Minister Bennett. The very nature of the Conservative Prime Minister was diametrically opposed to all of Archie's images. It was easy to correlate the exterior of Mr. Bennett with the privileged class. It was a simple matter to depict Mr. Bennett's exterior appearance with protectionism. Yet, in spite of this, Mr. Bennett remained an avid Dale fan, and requested many of his originals.

When this great era of cartooning is examined, many of you will wonder how a single mind could originate five ideas a week. Probably this is the question asked most often of a cartoonist, including myself. The fact is that a cartoonist does not write editorials, nor does he do the research necessary for a continuous string of editorials. But a cartoonist does read all the editorials and news stories each day, from all the papers at his disposal and, from these, originates a cartoon idea that will be approved or rejected by the editor.

Archie Dale, as you probably know, had the greatest galaxy of editorial writers of his period at his elbow, day after day. He attended editorial conferences with the great John W. Dafoe, Grant Dexter, T. B. Roberton, J. B. McRae, J. B. McGeachy, and a host of others. He also had the freedom of action, possible only under a great publisher like the late Victor Sifton.

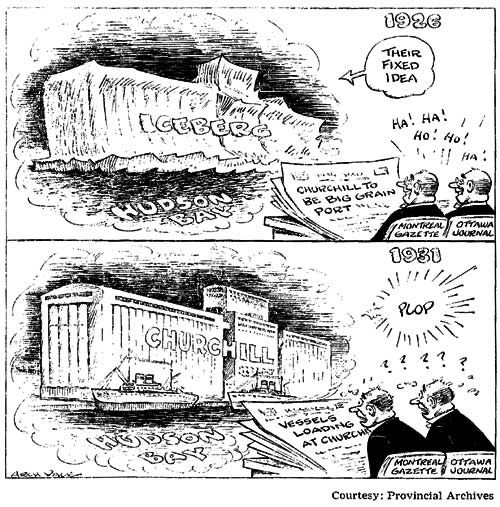

From these daily contacts, Archie absorbed and interpreted the Free Press attitude toward Bennett tariffs, toward the Conservative weakening trend on freight rates, towards the heavy unemployment of the '30s, and failure of the Conservatives to cope with the problem. But it must be remembered that his graphic invective was also aimed on many occasions at the Liberals.

I had the privilege of observing Arch personally during some of the best periods when Liberal policy was under fire from the Free Press. The most famous period, I believe, was when Jimmy Gardiner, then Minister of Agriculture in the Liberal government, signed the United Kingdom Wheat Agreement following the Second Great War. Archie acquired the editorial tone easily - remember he had slugged it out unsuccessfully on a Saskatchewan homestead - and kept up an embarrassing cartoon tirade against Gardiner and Liberal policy.

I said that I was privileged to work with Archie during his last years at the Free Press. Specifically, this was from 1945 to 1954, when I succeeded him as the editorial page cartoonist. Thus, I feel at least partially qualified to describe a typical Dale day. It started at ten a.m, when he arrived at the office. Sometimes, we would carry on a reasonably incoherent conversation for several minutes before he tried to jell an idea for the day's cartoon. Then, with the habitual hand-rolled stub of a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, he would head for the editor's office. He was soon back at his desk muttering good solid Scot's oaths at the perversity of his editorial colleagues for their seeming lack of attention to him, or their mild criticism of his ideas. He would make many sortees back and forth, until finally the editor would put his approval on the idea. Arch would then get back to his drawing board. He would first pencil in his idea ... then ink in the finished product. Tobacco siftings littered the drawing-board, which was always an untidy mess. But through the litter, the forms took shape ... the idea took form, and another barb was headed for the page. One of the mysteries that baffled me continuously was how the cigarette was always half-smoked. I don't recall ever seeing him light a fresh cigarette.

With the cartoon on the way to the engraver, Archie disappeared daily to gather new strength from the grass-roots for the day ahead. I think it would be unfair to suggest that the main attraction was beer. It was, rather, that the world of politics and social strata were unreal to him, and he had to return to the world he knew and understood, when he had freed his mind of his higher calling.

Arch, in the time I knew him, had developed a few idiosyncrasies. He hated drawing girls ... and, whenever he had to include them in a cartoon, he would turn to me, or someone around, and have us pencil in our version of a pretty girl. This was rather amusing since, despite his claims that he couldn't draw them, I checked back in the files and found that his early versions of the female form were just as seductive as any of our later efforts.

At other times, he would protest that he could never draw George Drew. Invariably he would come to me to pencil in a caricature of Drew, but when he penned in the finished cartoon it was always his own figure.

William Aberhart, the Social Credit founder in Alberta, was one of Arch's favourite targets. He pinioned Aberhart with devastating effect on his A plus B Theorem. He followed him around with his promised $25-a-month dividend, and Archie rose to unprecedented heights when Aberhart threatened to pass legislation to muzzle the press. There are many people here, who will remember Archie's work, centered around Doe Sawbones, Old Man Grouch, and all the other immortal Doo Dads, but you will also remember that the creator of these happy, little people was also a powerful force in shaping the Western farmers' discontent into a powerful and potent political group which became a dynamic factor in the farmers' battle against freight rates, injustice in the grain trade and high tariffs. Throughout the Bennett era, the Aberhart era, the King era, Archie threaded the cartoon tone of a violent Canadian political history. His record of these years is on permanent file in the Winnipeg Free Press, and may well have helped to mold the trends of these hectic years. I think this will become apparent when I show the slides. These will fix the dates firmly and much more adequately than I could by talking about them. But it will be apparent to you how, from the gateway city in far-away Western Canada, the happenings and events in Ottawa could be brought to life and influence a nation; how a cartoon produced in a paper here, thousands of miles from Berlin, could be reproduced in Berlin newspapers as a symbol of hatred.

I would like to express my gratitude for the opportunity you have given me today, to present this brief resume of the life and times of Archie Dale, whom I loved and revered, and who preceded me in the cartoon chair that I hope I shall never leave.

Source: Provincial Archives of Manitoba

I would be quite wrong to close without stating that I do not intend to imply that because Archie Dale's barbs were mostly against the non-Liberal parties, that these parties were always wrong. This would be an injustice. It is simply that Archie grasped his pen in a Liberal stronghold, and that other parties supplied the background. In this great game of political cartooning, Death was the loser when Archibald, a brilliant and beloved cartoonist passed on, for, as long as the files of the Winnipeg Free Press live, so will Archie Dale remain interwoven with your lives and mine.

Page revised: 22 May 2010