Manitoba Pageant, Spring 1976, Volume 21, Number 3

|

The group of derelict brick houses stand in a small clearing staring with vacant eyes across the scrabble of weeds at the row of towering spruce; more spruce crowd behind them casting deep shadows and a peculiar stillness weighs the air. Close by, at the foot of a long hill, there is a jumbled mass of masonry resembling the ruin of a Roman viaduct. A little river steals around and beneath the great blocks to run silently away over granite steps.

This was all that remained of Old Pinawa; thus it stood for many years largely forgotten and seldom visited. During the summer of 1969, the brick houses were demolished and according to unconfirmed rumor there may be some scenic development of the site.

Here was the first hydro-electric development of the Winnipeg River for the purpose of serving the needs of a growing Winnipeg. For close to fifty years, it was a busy and self-contained community. Then the towering spruce formed a neatly clipped hedge and the scrabble of weeds was a smooth expanse of lawn. The brick houses and the row of frame dwellings, long since removed, were alive with warmth and family life and bright with flowers. There was a school, a post-office and general store; there was a large garden to supply fresh produce and sheep grazed in the fields; a herd of cattle supplied milk. Religious services were given by an Anglican minister and a Roman Catholic priest from Lac du Bonnet. Medical needs were met by a doctor from the same centre.

It was a way of life which seems idyllic in contrast with the strident present. Separated from the nearest centre, Lac du Bonnet, by the river and ten miles of corduroy road, the one hundred or so inhabitants felt little sense of isolation. There were many recreations. In summer there was swimming and tennis, fishing, picnics and hiking. In winter, tobogganing, snowshoeing, skating and curling.

Pinawa is an Indian name meaning ‘sheltered waters,’ a name as apt for the Channel as Indian names traditionally are. In 1911, Government surveyors named the stream Lee River, a reasonable English equivalent. In general usage, however, that portion upstream from the powerhouse site is still referred to as the Pinawa Channel and the downstream portion retains the name of Lee River.

In the late 19th century, Winnipeg was a rapidly expanding boom town known as the ‘Chicago’ of Canada. An interesting account, relevant to the electrical development of the early days, may be found in an article in the Manitoba Hydro publication Image of Autumn 1964. According to this account, the Light first came on in Winnipeg when the Hon. R. A. Davis, proprietor of the famed Davis House on Main Street, illuminated the front of the premises with an arc light. The year was 1879 and, quoting from Image, ‘this took place six years before Edison’s first incandescent lamp—and exactly three years before Alexander Graham Bell spoke the first complete sentence over a telephone.’ Here was the beginning of Winnipeg’s well-deserved reputation as the City of Lights. The famed arc lights of Paris (all sixteen of them at first) were not in use until 1878.

As the population of Winnipeg mushroomed, the necessity for electrical power became evident to the enterprising and far-sighted. The potential of electricity was unimagined by the average person at the turn of the century. The Winnipeg Electric Street Railway Company which operated a steam plant in Winnipeg the capacity of which was 7000 h.p. had, before the turn of the century, been investigating the possibilities of hydro-electric power to fill the demands which were bound to come. The Winnipeg River had been surveyed for its potential and land purchased in the Seven Portages area (Seven Sisters) as early as 1897.

This great river had first been surveyed by LaVerendrye’s son from Kenora to Lake Winnipeg, its contours mapped and its many falls measured. LaVerendrye had named it the Maurepas River in honour of the French Minister of Foreign Affairs.

With falls to choose from, one wonders at first thought, at the site chosen for this initial development. The late Mr. K. C. Fergusson of Great Falls, who became Superintendent of WESR Co. hydro plants in 1922, gave the explanation. The Pearson Engineering Company of New York was hired to survey for the likeliest site. Working after freeze-up, unaccustomed to -30 degree temperatures, they found that the Seven Sisters area was frozen over but the water was running in the Channel. Accordingly, it was recommended that the Pinawa Channel site be developed which, it was felt, would give a monopoly on hydro power. The project got underway. A franchise was granted in perpetuity and financial backing was obtained from London, England. Hugh L. Cooper of the Pearson Engineering Company was chief engineer and, it should be noted here, this same gentleman built the first hydro plant in Russia on the Dnieper River and was a sponsor of the Passamaquoddy Tidal Development of the Bay of Fundy, a project which never got underway. Walter Whyte was assistant and resident engineer.

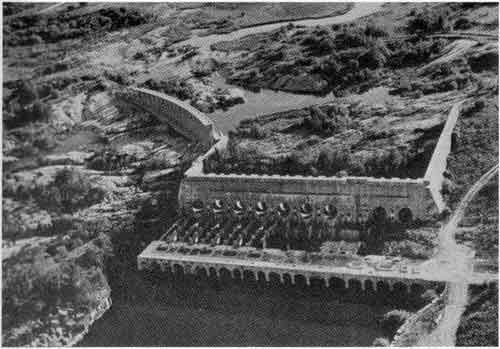

Construction was begun in April 1903. The Channel has never been more than a large creek so a diversion dam 1800 feet long was built at the junction of the by-pass and a control dam below that, both eight miles above the site of the power house. The railhead was at Lac du Bonnet and at that time there was no bridge across the Winnipeg River. The tons of heavy equipment were towed across the river on barges by a steam tug operated by Harry Nystedt during open water. The dock was located near the present location of the grain elevators. In winter, the equipment was hauled over the ice. Miles of corduroy road were constructed on the other side, one going past Simonson’s house and the other following the trans-mission lines. Anyone who has ever encountered muskeg will appreciate the difficulties involved in moving heavy equipment over such terrain and may well imagine the consternation when one generator went off the road and into the swamp. According to Mr. Fergusson, this became the ‘Jonah’ of the plant, slipping a cable on another occasion and smashing a wall, and causing some flooding in the power house another time. This is Precambrian Shield country and great rock cuts were necessary throughout the Channel to the control and diversion dams, an arduous and delicate under-taking. At this time, the going wage for labourers was ten cents an hour for a ten hour day. The rock drillers received fifteen cents an hour.

The official opening of the Pinawa Dam was a milestone in the history of Manitoba. The following despatch is quoted from the Winnipeg Free Press of 29 May 1906:

Lac du Bonnet Power Is Ready

The first hydro-electric plant of any size between Sault Ste. Marie and the west slope of the Rockies. It is the first of many proposed hydraulic sites for the Winnipeg River which Ishram Randolph, the Chicago expert, states is capable of almost one million H.P.

When work began, three and a half years ago, plans were for a plant producing 15,000 H.P. but since then, Winnipeg has forged ahead and the plans are for 30,000 H.P. with cost of $3,000,000.

Controversies have raged over the respective merits of other power sites on the river.

The Street Railway Company is now developing 7,000 h.p. of steam at their station on Assiniboine Avenue and it is this that the present development will supplant.—Work on the receiving station on Mill Street has been completed. At the present time, it is the intention to generate 10,000 h.p. but it will take only a few weeks to double or triple this if necessary.

At the power house, the energy is generated at 2,200 volts. From the generators it is wired to the transformer station where the voltage is raised to 60,000 volts which is economical for long distance transmission. It is sent as 3 phase current to Winnipeg over a special transmission line (double circuit) which is one of the features of the development work. At Winnipeg, another large transformer station has been installed, where the current is ‘stepped down’ to different voltages and forms of current for local distribution.

Dam—40 feet at highest elevation, 22,000 cubic yards of concrete—one part cement, three parts clean sand and five parts broken stone.

Dam is in three sections. In the centre, the section is 200 feet in length through which the intake pipes pass to the wheels. To the right, there is a wing wall running at right angles for 160 feet upstream and then deflecting to an angle of 45 degrees to the north for another 120 feet. On the south side, there is a similar wing wall for 105 feet from the end of which is carried the over-flow dam—500 feet in length, which is used for regulating the height of water in the forebay. When the water rises to the top of the overflow dam, the surplus flow escapes by this avenue to the river below and allows floating ice to escape.

The power house and transformer station at the river form one big building about 700 feet in length.

Pinawa Channel School and log cottages of W. E. St. Rly. Co. at Pinawa, 1914

The official ceremonies took place on 31 May 1906 with many dignitaries present and following are excerpts from the account of that day carried by the Winnipeg Free Press again:

Power Turned On At Lac du Bonnet

Lt. Gov. Sir Daniel McMillan yesterday inaugurated the great enterprise which the Winnipeg Electric Street Railway Company have had under construction for two years for developing energy on the Pinawa Channel of the Winnipeg River, and the opening of which really marks a new era in the development of Winnipeg —The four generators, each with a capacity of 2,500 h.p., will give the Company 10,000 h.p. from the Winnipeg River. By the end of September, the Company will have another four generators with a capacity of 5,000 h.p. each.—The buildings are all of fire-proof construction. Part of the power house remains to be completed. However, the immense work of cutting a channel through the ledges of rock that projected across the Pinawa and the building of an immense dam with reinforced concrete is done and will control water in volume large enough to generate power in accordance with the engineer’s plans.—Sir Daniel McMillan commended the Company on the undertaking and said it had required `courage and enterprise to enter upon the undertakings of the magnitude of that which they had just seen’. He also said that the growing importance of Winnipeg was testified by the need for harnessing the power of this great river and compared the event to being second only in importance to the arrival of the first locomotive.—Mayor Sharpe said the concrete work was the best in Canada.

With regard to Mayor Sharpe’s words, it is worth noting that some years after the dam closed down in 1951, the site was used by the Army for demolition experiments. The great blocks of concrete gave way but did not disintegrate and they lie there today, mute testimony to the excellence of the original construction.

The first power from the new hydro-electric plant flowed through the transmission lines to Winnipeg on Saturday, 9 June 1906. Forty-five years later, redundant because of the greater hydro-electric complexes which have completely tamed the Winnipeg River, the last switch was turned off at 17:58 hours on 21 September 1951. The members of the last operating staff at Pinawa were: George Cobb, operator, H. Lundquist, oiler, J. Ventz, oiler, and L. Peterson, cleaner.

Comfortable quarters for employees at water power plant, Pinawa, 1908

Once the name Pinawa was synonymous with the first great step forward in Manitoba in the use of natural resources scientifically for the service of society. It is singularly appropriate that Atomic Energy of Canada, Ltd. chose to perpetuate the lovely old name by giving it to their atomic reactor complex and townsite in the Whiteshell, another first in Manitoba concerned with harnessing another kind of energy for the benefit of man-kind.

* * *

We are indebted to the late Mr. K. C. Fergusson of Great Falls for much of the information in the foregoing article.

See also:

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Pinawa Hydroelectric Power Dam (RM of Lac du Bonnet)

Page revised: 26 February 2014