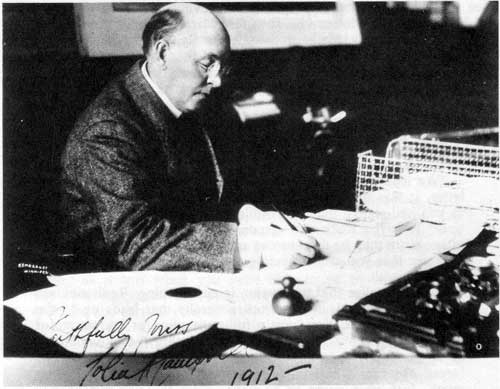

by W. Leland Clark

History Department, Brandon University

Manitoba Pageant, Winter 1974, Volume 19, Number 2

|

The Hon. Colin H. Campbell, M.L.A. for Morris and Minister of Public Works in the Rodmond P. Roblin Ministry, was stricken by a severe illness on February 15, 1913, the very day on which the session of the Manitoba Legislature was prorogued. Hoping to benefit from the traditional cure of rest and sunshine, the Minister travelled to Kingston, Jamaica, where he, unfortunately, almost immediately suffered from an attack of paralysis. Following a considerable amount of time spent in the care of medical authorities in the Eastern United States, the Minister and his ever-present wife, Minnie Julia Beatrice Campbell, journeyed overseas in the continuing search for medical relief. There, they spent the winter of 1913-1914 and what proved to be the majority of his remaining days. Despairing of hope for a full recovery, the Hon. Colin and Mrs. Campbell returned to Manitoba in the late summer. He died shortly thereafter on October 24, 1914, at the relatively young age of fifty-four.

While Colin Campbell was absent from Manitoba, several Manitoba politicians wrote with varying degrees of frequency in an effort to keep the absent Minister informed of developments within his home province. In view of the scarcity of primary sources for that particular political era, the letters written to Colin Campbell during his period of absence are of value and interest to the historian. The fact that several of these letters were written by Premier Roblin in what proved to be a crucial stage in his political career means that they are even more of interest to the reader today.

Premier Roblin wrote several times during a period of time that extended from July 9, 1913 to August 21, 1914. The nature of his letters would vary as he became more aware of the gravity of Campbell’s illness. Thus, on July 9, 1913, Premier Roblin wrote a cheerful, reassuring letter that said virtually nothing, probably on the assumption that the Minister would soon return and there would then be time for serious political discussion. After the predictable comments on Campbell’s health and an expression of hope that “the trip that you are about to take will end in your complete restoration ...” [1] Roblin turned to politics in an almost “breezy” fashion:

Everything is moving along here in the same way ... I am going in a few minutes to Elm Creek; expect to dig a ditch or build a road to suit some of my friends and constituents before I return.

The weather is splendid: crops, [2] I think, are better than they were last year—better paying crops ...

The tenders have been received for the new Parliament Buildings: only two came in, Lyall and Tom Kelly. They are practically together, but Kelly is a few thousands dollars the lowest. The amount is, in round figures, $2,800,000.00 ... [3]

We are going on well at the Agricultural College: the buildings are progressing finely. We will move in this fall undoubtedly ...

Everything is splendid here. The party united enthusiastic and in fact aggressive. Am just starting Provincial organization. [4] Have made Fulcher the general English organizer and Alderman Stafanik for the Ruthenian or foreign element. Fisher is for the present acting as secretary, not doing any outside work ...

Your lists were well looked after, although there is no possibility of an election being held on them unless some very unforeseen thing happens ... [5]

Premier Roblin’s next letter of September 9, 1913 was also full of confidence and reassurance. The harvest was underway and it was “undoubtedly the best in the history of Western Canada.” [6] The Parliament Buildings were under construction and they were “sinking the caissons now.” [7] The political scene still remained calm for, as Roblin noted, “The Free Press has not had any spasms for several days, but I suppose it will break out in a violent one soon, as it is impossible for them to remain passive for any length of time.” [8] Finally, Roblin noted some concern for his own health (he had taken the baths at the Elmwood Sanitarium [9] for his lumbago), and that he was delighted with the news that Colin Campbell was expected to be back at his duties in four or five weeks.

Before those few weeks had passed, there was to be another Roblin to Campbell letter, dated September 25, 1913, containing the first ex-pressed concern for the political future of the Government.

We held a Council Meeting this morning, and I read your letter. It was quite disappointing, as we had counted definitely, as you had stated, that you would return in October. Mr. Coldwell [10] feels the work and responsibility of his dual position is rather more than he feels he can satisfactorily discharge, but they all agree that you are absolutely right in not taking any chances on your health.

We also realize that the session is approaching. Redistribution must be introduced, in fact work generally that leads up to the inevitable election. You have a full conception or knowledge of what all this means, and you also realize that the Government, as at present, is not any stronger than it ought to be. Your forced absence is certainly a great loss to us. We feel it very much. Just what ought to be done under the circumstances is very difficult for us to decide. [11]

Campbell’s continuing ill health and the approaching general election combined to cause considerable anxiety for Premier Roblin and his colleagues. As Roblin indicated in his next letter of October 6, 1913, the gravity of the situation was increased by the fact that Colin H. Campbell was generally regarded as the second in command to the Premier.

Since I wrote you last we have had many and serious Council meetings. Your statement that you would not return until next summer completely upset every member of the Government, including myself. You know the extent to which myself and colleagues depended upon you in the past, particularly when the House was in Session. No other member of the Government except myself ever pretended to have courage or knowledge to justify leadership.

For this reason, and in view of the fact that I have already two or three times in the past been unable to be present in the Session, and I am even now in not any better health than I ought to be, it has caused us to study the situation carefully. This was forced on us more particularly from the fact that the next Session will in all probability be the last before the General Election, and will necessarily be, if the usual tactics of the Opposition prevail, a bitter one. If anything did happen you can understand the condition the House would be in. In fact, every member of the Government say they cannot or will not go on without some man taking your place who is at least quasi qualified for leadership. It is a very sad and heart rending thing for me to say after our long years of closest and most cordial relations possible, but it is forced upon me, and I am sure you will, with that usual good judgment of yours, accept the situation philosophically.

In a word, it has been decided that we must take in another man to take your place. They will not convene the House as the Cabinet is now constituted. The names discussed are Aikins, Montague, W. J. Tupper, Sanford Evans, in the respective order in which they are set down. I, therefore, think that you had better send me your resignation as a Cabinet Minister, so that I can strengthen the situation as best I can. Realizing that no matter who I get, it will never be as satisfactory and as strong as it was when you were able to sit by my side and not only supported me when necessary, but to pick up the standard and carry it yourself when I was disabled.

I have not disclosed this fact to anyone, although John Haig [12] has a pretty good idea of the situation, as you sent him a copy of the letter you sent myself and colleagues, and he discussed it with some of the other members as well as myself, and also felt, in view of the attitude taken, that something would have to be done ...

My suggestion is that if you do not feel that you can stand the excitement incident to political life, that you hold yourself available to the Lieutenant-Governorship, [13] which will be vacant soon after you return, and which would give you every claim for honors from His Majesty. This, I am sure, could be arranged, although I have not told Rogers [14] or a living soul of my difficulties or of your condition.

I repeat that I am worried beyond expression at your continued ill health and your inability to take your old place. I am delighted that you are making progress, and if you come back able to take a place in the Government I shall certainly make provision for the Government party to secure the services of your splendid ability in the future.

I do not know what I can write more. I am so depressed at having to write this way that I have not heart for anything, but I am sure you will sympathize with me and send your resignation as early as you can. In fact, I would like for you to cable me on receipt something like the following—“Agree, Mailing”. I want to look the ground over and get my man as quickly as possible, and get an election. I do not know where the seat can be found, because I would advise you not to resign your seat in any case, and the probability is we would call a Session in December, as it will possibly be three or four months drawn out from what I hear, and if we hold an election in the summer we want all the time for organization that is possible. [15]

That the Minister resigned promptly in response to the above request is evident from the Premier’s next letter of November 10, 1913, in which he referred to the resignation received about a week before. Campbell’s resignation as Minister of Public Works had been followed by the immediate appointment of Dr. Montague [16] to that post. There still remained the problem of finding a seat in the Legislative Assembly for the new minister.

Lyle of Melita wishes to resign, as does Dr. Grain, Riley and Aimé Benard, at least they have all offered him their constituency. I just this morning had a letter from Mackenzie of Morris, saying that the Liberals would allow the Doctor to be elected by acclamation. They evidently think that you have resigned your seat. We expect a fight wherever we go. [17]

The sincere sadness of a Premier who had experienced the distasteful task of requesting the resignation of his principal lieutenant was apparent in this letter. In addition there was an awareness that his own personal role in Manitoba politics was nearing its end.

I may say that the acceptance of your resignation was one of the saddest things l have had to do in my life. It leaves me entirely alone insofar as the original Cabinet is concerned and as a member of the Legislature. I realize that it is only a matter of time, and possibly a very short one at that, when I too will have to withdraw. I wish from the bottom of my heart that I was out of office at the moment, and free from its cares, its worries and its responsibilities. I realize, however, that I cannot do that just now. I am, as you properly forecast, not at all in good health, and how soon it may entirely incapacitate me no one can foretell. [18]

The seat which the Roblin government selected for Dr. Montague was that of St. Andrews and Kildonan. The by-election there in late 1913 proved to be one of the most controversial in Manitoba’s history. When Roblin reported on it to Campbell, who was by then seeking the recuperative benefits of the Cairo sunshine, the final results of that by-election were not yet known. The by-election had been, the Premier wrote

... a wicked fight. The personal attacks on Dr. Montague were something exceeding anything I have heard of or seen in this Province before. They made every attack on him that was possible in connection with his private and public life, and did it by way of pamphlets and fly sheets printed in every language spoken in the division. [19]

While the Premier did not discuss, to any extent, the methods employed by the Government party in that much disputed by-election, he did note that bad weather had hampered some of their activities. Thus, he wrote that “Saturday, election day, was mud to the axles. I fancy there were 20 motor cars out of business as a result of the weather. We had over forty cars down there, but the mud road was so bad they were scarcely able to do anything only on that portion of it that is macadamised.” [20]

When Roblin wrote next on January 9, 1914, the challenge of the by-elections had been successfully overcome, [21] and the Legislature had been in session since December 11. While the Premier reported that the session had not as yet “excited any interest”, [22] the major problem then before the Government (but not yet before the Legislature) was a matter of considerable significance. Re-distribution was to precede an election in 1914 and there were many factors to be considered.

We have not got our re-distribution worked out yet but I am working on it every day. I have them in from all over the country, and lopping off and adding on makes considerable difficulty, and some of the members want to get rid of certain portions and to add some others which the parties who have them do not want to give up. However, we have decided upon some things.... For instance Avondale and South Brandon are to be merged into one, we are taking off a row of townships from Avondale and adding it to Deloraine, in which there is about 200 conservative majority; that should fix Reid [23] permanently ...

So far, there has been no proposition to change Morris ... However, after your letter, which indicates that you do not hope to contest it again, we will have another conference with Haig and others, and see what can be done to benefit everybody.

Winnipeg is to have six seats, divided into three districts of two each, Class A and B, the same as Toronto. We tried to work out your scheme of the whole city, but the committee after two weeks deliberation decided it was too dangerous ... [24]

This letter of the Premier’s also carried much news of home to the absent colleague in far-off Cairo. It had been an unusually pleasant winter, [25] the notorious Jack Krefchancko (sic) [26] had been arrested for the murder of a Plum Coulee bank manager, and Sir James Whitney [27] was seriously ill in New York City. The Premier noted as well that many residents of Winnipeg had left, or would be leaving, for Cairo where, it was anticipated, they would visit with the Campbells. [28] Finally, there was a further disquieting comment by the Premier as to his own health:

I may say I have not been very well myself; was in bed for a week, including Christmas. The same old trouble. I may have to go over and spend some time with your German doctor, as my heart seems to be very tired at times. [29]

Roblin wrote again just ten days later in response to a letter just received from Campbell. As with the previous correspondence, this letter was friendly and informative. However, there was less of political significance on this occasion. The fact that this letter was written so soon after the earlier one of January 9, 1914, could be the explanation. One suspects, however, that the relationship between Roblin and Campbell was slowly changing as it became increasingly evident that they would never be cabinet colleagues again.

There was, however, still political news of a rather general nature.

The Opposition never were as mild as they are this Session. I think there is a strong movement to unhorse Norris. [30] The Free Press has not mentioned his name editorially in three months. I am told from Ottawa that they are bound to drive him out. I shall make every effort to keep him where he is. I think he is necessary for our good, and ensures success. [31]

There was also a report on one of Campbell’s favorite pieces of legislation:

We have had some considerable discussion on your Children’s Protection Act, on the Truancy Bill, and are amending it with very strong clauses to cover all the points that are necessary for so-called Compulsory Education. [32]

Finally, there was a somewhat patronizing reassurance for the ailing politician that he could still be of value to his party.

You are quite right in assuming that I would be glad and all the others as well, to have the benefit of your advice in Council on all matters pertaining to public affairs here. You can be assured that you will be one of the most welcome around the Council board, no matter what your official position is, when you are able to do so ... [33]

As time passed so did the close relationship that had existed between the absent Campbell and the Manitoba Government. The Premier wrote his last letter on April 21, 1914, some three months later. In this letter Roblin clearly was writing to someone who was then quite removed from the political scene.

It did me good, and still does me good to look at the old familiar signature that I have seen on so many public documents, Orders-in-Council, etc. It is most pleasing to hear that you have made such a splendid recovery. [34]

There was rather depressing news of old friends.

A great many of them since you left have been called to the great unknown. Tomorrow, we bury Sir William Whyte. [35] He died in California, and his body reaches the City to-night. Many others have died that you know, among them Mr. Litchfield, who had charge of the McIntyre estate for so many years ... [36]

Inevitably, politicians writing to politicians must refer at some point to politics. This last letter was no exception, and in it is to be found the still present optimism for the future.

Judging by reports I am of the opinion that they [37] will have less in numbers in the new House than to-day. Certainly they will in the country districts. Winnipeg is somewhat uncertain, always is, by virtue of the large number of voters. The election cannot be held before the latter part of July, and may not be held until the fall. [38]

Finally, there were a few words on an issue that would prove to be most significant—and more damaging to the Roblin government than the Premier foresaw.

I delivered an address in Neepawa on the temperance question a few days ago. I understand you get the Telegram, so you will have seen it. It has cleared the air, steadied our friends, and thrown the other camp into consternation. [39]

The election results of July 10, 1914, presumably caused more “consternation” in the Conservative party than they did in the “other camp”. There is no record of any letter from Roblin to his ex-colleague after that fateful date and it remained for an old friend and the ex-Premier, Hugh John Macdonald, to convey details on the political misfortunes of the Conservative party.

At the present moment, the Government have a majority of four seats and there are three deferred elections yet to come off in the added territory. Dr. Montague who sits for St. Andrews and Kildonan had only a majority of three and a recount has taken place. I believe that there will also be several re-counts as there are two of the Grits, Macpherson of Portage, and Malloy of Carillon who have only seven to the good, so that it is really impossible to know yet what majority Sir Rodmond can count on. [40]

While Hugh John would be well aware of the thesis that elections are rarely won or lost on a single issue, he was quite certain as to the major cause of this particular setback:

It was, of course, mainly through the Coldwell amendments. [41] I very much feared that they hurt us, for having been through the long fight on the school question, I dreaded its revival and felt sure that it could not be touched by the Government without doing immense harm. [42]

Macdonald further suggested that some Government candidates had perhaps too readily shared their Premier’s self-confidence:

Hugh Armstrong was defeated by seven in Portage, mainly through over-confidence, I am told, and Albert Prefontaine lost his seat by the same majority through the same cause. [43]

The political future was, Macdonald concluded, full of uncertainty and he found the prospects personally disturbing:

... I am very much afraid that a man of his [44] temperament will find it difficult to carry through the next session with such a small majority without being driven by the badgering of the Opposition into his grave or the lunatic asylum. His health, I am afraid, is not all that his friends could wish it to be, and I look forward with a certain amount of alarm to the next meeting of the House, for I have always received so much kindness at Sir Rodmond’s hands that I naturally dread anything that I think may have an injurious effect upon him. [45]

The Campbell’s return to Winnipeg a few months before his death on October, 1914, terminated the correspondence of the preceding months. The historical significance of that correspondence lies both in what was said and what was not said. Premier Roblin, for example, had expressed initial concern as to the strength of his Government. His “right bower” was to be absent during important months preceding the 1914 General Election. The Premier also expressed concern for his own health (as did Hugh John Macdonald after that election) and, on one occasion, he seemed to envy Campbell’s detachment from the strain of office.

On the other hand, the Premier did not display any real awareness of the significance of the issues that were before the Legislature and would soon be before the electorate. He wrote without any apparent doubt that he, and the Government, were successfully resolving the questions of temperance and compulsory education. The Grits, he confided in Campbell, were divided and Norris’ position as leader was insecure.

The Government was perhaps relying on the traditional techniques of electioneering. “Ditches were being dug” and redistribution had been presumably completed satisfactorily. The Government was, indeed, optimistic about its electoral future. There was no expressed awareness of what the 1914 election was to bring.

One might suggest that Premier Roblin purposely underestimated the significance of these political problems in order to avoid alarming his ailing colleague. He had not, however, refrained from expressing his earlier concern when he wrote of his own health and the weaknesses of the Cabinet.

One can conclude, therefore, that Premier Roblin was unaware of the extent of the political opposition that was developing in Manitoba when he wrote his last letter to “My Dear Campbell” on April 21, 1914. Whether he remained unaware as his Government went to the polls on July 10, 1914, is unknown. It was the expressed opinion of Hugh John Macdonald that he did. If one does conclude that the Roblin Government was largely unaware of its own weaknesses on the eve of the 1914 General Election, there remains the difficulty of explaining such unawareness. Could part of the answer be the absence, during those crucial months preceding that election, of Roblin’s “right bower”? One suspects so.

1. Rodmond P. Roblin to Colin H. Campbell, July 9, 1913, Colin H. Campbell papers, Correspondence May-September 1913, Public Archives of Manitoba (hereafter cited as P.A.M.).

2. The frequent reference to crops and harvest conditions undoubtedly reflect both the political and economic significance of agriculture in Manitoba in 1913-1914.

3. The reference to Kelly and the Parliament Buildings contract does not indicate any “special” relationship between Kelly and the Government.

4. The implication is that Roblin regarded party organization as his own personal responsibility.

6. Roblin to Campbell, September 9, 1913, Colin H. Campbell papers, Correspondence May-September, 1913, P.A.M.

10. The Hon. G. Coldwell, M.L.A. for Brandon and Minister of Education, had been Acting Minister of Public Works in the Hon. Cohn Campbell’s absence.

11. Roblin to Campbell, September 25, 1913, Colin H. Campbell papers, Correspondence May-September 1913, P.A.M.

12. John T. Haig was a prominent Winnipeg Conservative and, evidently, a close friend of Colin Campbell.

13. Sir James Aikins would become Lieutenant-Governor in 1916. Aikins, M.P. for Brandon since 1911, was one of those mentioned earlier as a possible successor to Campbell. He did become leader of the Conservative party in 1915 after Roblin’s resignation.

14. The Hon. Robert Rogers was then Minister of Interior in the Borden government. Matters of patronage for Manitoba were clearly his responsibility.

15. Roblin to Campbell, October 6, 1913. Colin H. Campbell Papers. Correspondence, October-December, 1913. P.A.M.

16. Dr. Montague has been listed as the cabinet’s second choice in the letter of October 6. There is no explanation as to why Montague was appointed rather than James Aikins, the expressed first choice.

17. Roblin to Campbell, November 10, 1913, Colin H. Campbell Papers, Correspondence October-December, 1913, P.A.M.

18. Ibid. It would appear that Roblin’s poor health might well have led to retirement in the near future, irrespective of any question of political impropriety.

19. Roblin to Campbell, December 1, 1913, Colin H. Campbell Papers, Correspondence, October-December 1913, P.A.M.

20. Roblin to Campbell, December 1, 1913, Colin H. Campbell Papers, Correspondence October-December 1913. P.A.M.

21. Roblin reported that Dr. Montague had won the St. Andrews and Kildonan by-election by a margin of 418 votes. In addition, the Government party had also won a by-election in Macdonald constituency, with the majority of 923 being “a very considerable increase over the last one.” Roblin to Campbell, January 9, 1914, Colin H. Campbell Papers, Correspondence, 1914, P.A.M.

23. J. C. W. Reid was the Conservative M.L.A. for Deloraine. In the 1910 General Election he won the seat by a margin of six votes over his Liberal opponent, R. S. Thorton. Presumably. Roblin was attempting to strengthen Reid’s position although the phrase “fix Reid permanently” is somewhat ambiguous. In any event, Reid lost the seat in 1914 by a majority of 204 votes.

25. The Premier notes that he had that day, for the first time, abandoned his summer overcoat for winter attire.

26. Krafchenko’s arrest, his later escape, and his eventual execution, was of much interest to Manitobans in 1913-14.

27. Sir James Whitney, Conservative Premier of Ontario, had been seriously ill since December. He died on September 25, 1914.

28. It would appear that Cairo met the needs of winter-weary Manitobans in pre-World War days as does the southern United States and like areas now.

30. T. C. Norris, M.L.A. for Lansdowne, was elected House Leader in 1909 and Liberal party leader in 1910 on the eve of the election.

31. Roblin to Campbell, January 19, 1914, Colin H. Campbell Papers, Correspondence, 1914, P.A.M.

32. Ibid. The amendment in question would fail to convince the electorate that the Roblin administration was taking the necessary steps to ensure a universal and unilingual educational system. This failure proved to be a major issue in the 1914 General Election.

34. Roblin to Campbell, April 21, 1914, Colin H. Campbell Papers, Correspondence 1914, P.A.M.

35. Sir William Whyte was vice-president of the CPR when he retired in 1911. He had been a prominent citizen of Winnipeg for many years.

37. The Liberal opposition would win 21 seats in the 1914 General Election. They had 13 members in the House at the time when Roblin was writing this letter.

40. Hugh John Macdonald to Hon. Colin H. Campbell, July 17, 1914, Colin H. Campbell Papers, Correspondence 1914, P.A.M.

41. The Roblin Government insisted that the Coldwell Amendments of 1912 were designed only to clarify certain sections of the School Act. Many critics believed that the Amendments were designed to re-introduce certain aspects of separate schools into Manitoba.

43. Ibid. The letters suggest, but do not prove, that one of the major factors in the Roblin Government’s setback in 1914 was its failure to perceive a fundamental change in electoral attitude.

45. Ibid. This is an interesting comment in view of the fact that so little is known of the relationship between these two men. Macdonald might well have envied the political success of Roblin who replaced him as Premier in 1900 while he, Macdonald, was to end his political career in the futile attempt to defeat Clifford Sifton in Brandon.

Page revised: 20 July 2009