by E. Gwyn Langemann

Parks Canada, Calgary

|

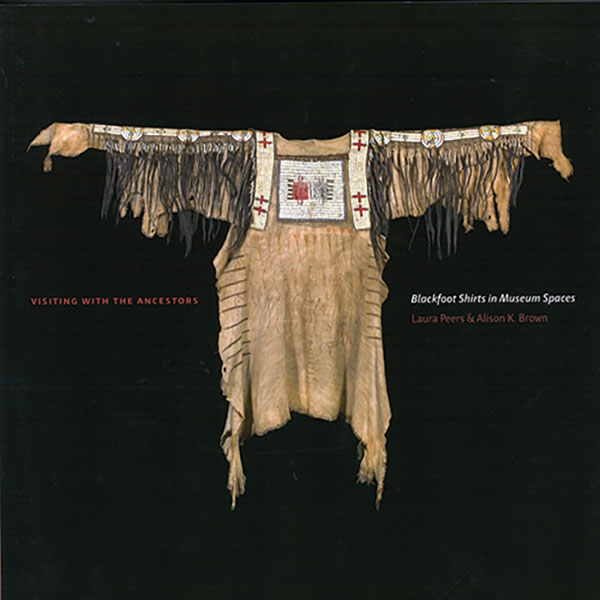

Laura Peers and Alison K. Brown, Visiting with the Ancestors; Blackfoot Shirts in Museum Spaces. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2015, 218 pages. ISBN 978-1-77199-037-0, $39.95 (paperback)

In 1841, Sir George Simpson (Governor-in-Chief of the Hudson’s Bay Company) and his secretary Edward Hopkins visited Fort Edmonton during an extensive inspection tour, where they were presented with five Blackfoot hide shirts and pairs of leggings. The circumstances of acquisition are not clear. The Fort Edmonton journals from this period have not survived, but Simpson’s diary notes an unusually large encampment and a visit from nine Blackfoot chiefs. This was a period when trade relations with the Blackfoot peoples were not straightforward, and the shirts were likely a formal diplomatic gift made by the chiefs to Simpson, in order to establish a relationship. Some 200 objects collected on this tour were kept by Hopkins and displayed in his Montreal home. He retired to England, and after his death in 1893, they came into the keeping of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University.

In 1841, Sir George Simpson (Governor-in-Chief of the Hudson’s Bay Company) and his secretary Edward Hopkins visited Fort Edmonton during an extensive inspection tour, where they were presented with five Blackfoot hide shirts and pairs of leggings. The circumstances of acquisition are not clear. The Fort Edmonton journals from this period have not survived, but Simpson’s diary notes an unusually large encampment and a visit from nine Blackfoot chiefs. This was a period when trade relations with the Blackfoot peoples were not straightforward, and the shirts were likely a formal diplomatic gift made by the chiefs to Simpson, in order to establish a relationship. Some 200 objects collected on this tour were kept by Hopkins and displayed in his Montreal home. He retired to England, and after his death in 1893, they came into the keeping of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University.

This collection is unique; there are few surviving examples of such early shirts. Three are hairlock shirts, adorned with locks of either human or horse hair, and panels of intricate quillwork; one shirt also has painted war honours. The fourth has long hide fringes and quillwork, and the fifth is a plainer ‘working’ shirt. When two Blackfoot elders visited the Pitt Rivers Museum in 2003 for another purpose and saw the shirts, they immediately began to consider how to bring them home. They had never seen such shirts before. These shirts are not merely ethnographic objects. Hairlock shirts are powerful, sacred beings, given to the people to commemorate a relationship with the Above Beings. Their origin story has Sun giving one to Scarface, to commemorate his war victory over dangerous cranes, and teaching him that hairlocks are added to a war shirt to mark war coups.

This absorbing book describes the process and impact of bringing the five shirts back home to southern Alberta for a visit in 2010, where they were hosted by the Glenbow Museum in Calgary and the Galt Museum in Lethbridge. The Glenbow had an established relationship with the Kainai, Piikani, Blackfeet, and Siksika communities, and indeed has pioneered a policy of unconditional repatriation and a formal collaborative approach with the Blackfoot for understanding and maintaining the collections. [1] The Galt Museum, near the Kainai and Piikani reserves, used this visit to begin a relationship.

Blackfoot elders and ceremonial specialists wanted relationship building to be at the core of this account. The background chapters briefly consider the Blackfoot world, traditional clothing, the origin and role of hairlock shirts, and the relationship of the Blackfoot with the fur trade. The central chapters consider the process of setting up the visit, the relationships between the museum community and the Blackfoot communities, the rippling impacts on all participants, and the ongoing dialogue and learning since the visit. The overarching narrative of the book is by Peers and Brown, but they include substantial quotes from many people to illustrate the visceral and emotional impact of seeing and touching the shirts.

Contemporary Blackfoot had not seen hairlock shirts. Hardly anyone knew the ceremonial protocol or had the rights to handle these sacred objects, and opinions varied on whether the shirts should even be handled and displayed. In the end, it was decided that the community and youth would benefit from this opportunity, and ceremonialists worked out a new relaxed protocol so that the shirts could provide a bridge between the ancestors and the coming generations. The Pitt Rivers Museum also relaxed some of its protocol, and allowed a much greater degree of handling than usual. In addition to the people who visited the public museum exhibits, some 550 people from the Kainai, Piikani, Siksika, and Blackfeet communities participated in smaller sessions where they could closely examine and handle the shirts.

I reviewed an earlier book by Peers that describes a similar encounter, where Haida came to the Pitt Rivers and British Museums to visit Haida objects. [2] These are similarly formatted books, presenting an encounter between a source community and objects that have long been in a museum’s care. The earlier book had more discussion about the theory of encounters and about museum staff learning to accept the Haida need to touch and handle the objects. In contrast, museum staff planned the Blackfoot shirt visits around this need, providing ample opportunities for handling. Visitors were able to try on replica versions of the shirts, made by Sylvia Weasel Head. More significantly, this time the objects went home to their communities. I think this happened for several reasons: Peers and Brown already had established relationships with the Blackfoot communities through their own earlier research, in which they had been mentored by Glenbow staff; the Glenbow and Galt provided the loan a safe and suitable home that the Pitt Rivers Museum and the Blackfoot were both comfortable with; and the Blackfoot, used to their dealings with Canadian museums, were more insistent on an actual return. For me, the Blackfoot shirts volume is the more satisfying read, because it jumps past the theory, and focusses on the actual visit home, the relationships, and the ongoing conversations and learning on all sides.

A chapter considers how the shirts continue to inspire students, teachers developing curriculum, ceremonialists, quillworkers, seamstresses, and artists in the Blackfoot communities, as well as the museum staff. Ramona Big Head, then a teacher at the Kainai high school, says, “[P]eople started asking questions and we were being led to people who knew what they were talking about...and it’s like we opened up a box of knowledge that we didn’t realize we had.” The impacts will be long term, awakening interest and dormant knowledge that may take time to flourish. Frank Weasel Head noted that Blackfoot youth can struggle to see a way forward to identity and achievement in education, business, or service. “Our history is oral. So this was their education, this was their certificate. So we can show young people: hey, you want to be like this, you want to be able to wear this? You better achieve it! That’s the other impact of the shirts. I don’t look only at the spiritual.” One example of the spiritual benefit is that Kainai, Piikani, and Siksika combined their knowledge and used one of the museum shirts to transfer the rights to hairlock shirts to several people, thereby reviving a dormant ceremony.

The Blackfoot have gone through troubled times since 1841, and it is unlikely that these shirts would have survived in the community. Many Blackfoot recognize an important role for museums in preserving things, but this role of necessity is evolving into one of mutual learning and support. The shirts came home for a reason. There is a chance for the communities to restore cultural confidence and knowledge from the objects and beings that have been preserved in museums. Narcisse Blood asks, “[W]ho are you preserving them for?” Canadian museums, living with the source communities as neighbours, are developing answers that include improved access and repatriation. In Alberta, there is legislation that applies to repatriation of sacred objects from the Royal Alberta Museum and the Glenbow Museum collections. British museums, so far away and with collections from such a multitude of source communities, are developing different answers, and emphasize a responsibility for preserving items for universal benefit.

Peers and Brown explicitly recognize that the Blackfoot shirt project came out of the context of the relationship and repatriation work of the Glenbow. However, there is as yet no mechanism for repatriating the shirts from the Pitt Rivers Museum, and no institutional appetite to do so. The final chapter in this book explicitly addresses the question of why the shirts were not repatriated, showing that the authors are well aware of how uncomfortable and unresolved this question is for both the Pitt Rivers Museum and for the Blackfoot. The successful encounter and the powerful community voices presented here should build a case with the Pitt Rivers Museum for increased access to collections for their many source communities.

Successful encounters between museums and Indigenous communities arise from the personal relationships that are built up and sustained over time. I read this book acutely aware that four people intimately involved with the Blackfoot shirt project have recently passed away: Piikani elder Alan Pard (the only person with rights to the hairlock shirts at the beginning of this project), Kainai elders Narcisse Blood and Frank Weasel Head, and Glenbow Director of Indigenous Studies Gerald Conaty. All of these people had mentoring relationships with the authors. All had mediating roles, interpreting the protocols of their own communities to the other, bringing together the museum and Blackfoot communities because they could see the value of these exchanges. What will maintain these relationships, now that the individuals are gone? It will take more than occasional visits home by the important objects.

In 2017, Bob and Priscilla Janes endowed four scholarships for Blackfoot students at the University of Lethbridge, in honour of these four men. Alison Frank is one of the first recipients, and at the scholarship announcement, I heard her speak eloquently about charcoal drawings she made of these Blackfoot shirts. Stitch by stitch, quill by quill, she drew these shirts larger than life to learn them by heart, and to immerse herself in a conversation with the ancestors. Her encounter with these shirts opened a path of engagement with her culture and education. This is the reason we should be working to make these encounters easy and accessible to people in their own communities, and not an occasion so uncommon that it deserves a book.

The book is handsomely produced, with a generous number of colour plates. The single map, however, does not reference most of the places and geographical features discussed in the cultural and fur trade background chapters. Two scenic photographs show key places in the cultural landscape of traditional Blackfoot territory, but the significance of these features is not discussed anywhere.

1. Gerald T. Conaty (ed), We Are Coming Home; Repatriation and the Restoration of Blackfoot Cultural Confidence, Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2015.

2. E. Gwyn Langemann, Review of C. Krmpotich and L. Peers, This is Our Life: Haida Material Heritage and Changing Museum Practice, 2013. Manitoba History, 79 (2015): 54-55.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 31 March 2021