by MaryLou Driedger

Winnipeg, Manitoba

|

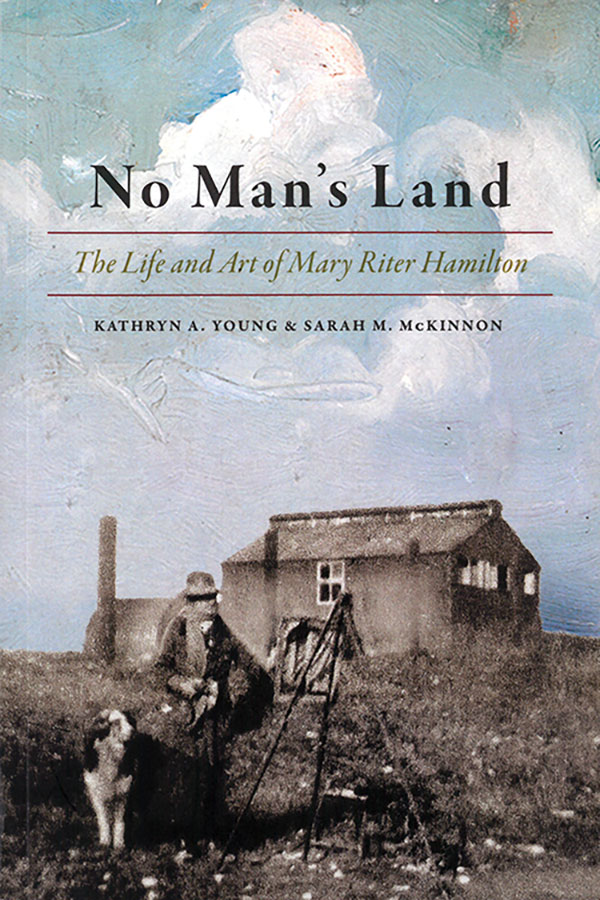

Kathryn A. Young and Sarah M. McKinnon, No Man’s Land: The Life and Art of Mary Riter Hamilton. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2017, 272 pages. ISBN 978-0-88755-811-5, $27.95 (paperback)

Easter Morning by Mary Riter Hamilton has been on display regularly at the Winnipeg Art Gallery since I started working there as a guide five years ago. In the painting, a young girl in a dark red apron, black dress and snowy white cap sits serenely on a short wooden bench. Her hair is neatly parted in the middle, and she has an endearing cleft in her chin. She is holding a sprig of greenery and is fin-gering a rosary. She seems comfortable in her stocking feet, but we can see the pair of wooden shoes she must have been wearing abandoned on the floor. It is an intimate, gentle portrait that exudes a sense of peace.

Easter Morning by Mary Riter Hamilton has been on display regularly at the Winnipeg Art Gallery since I started working there as a guide five years ago. In the painting, a young girl in a dark red apron, black dress and snowy white cap sits serenely on a short wooden bench. Her hair is neatly parted in the middle, and she has an endearing cleft in her chin. She is holding a sprig of greenery and is fin-gering a rosary. She seems comfortable in her stocking feet, but we can see the pair of wooden shoes she must have been wearing abandoned on the floor. It is an intimate, gentle portrait that exudes a sense of peace.

Easter Morning was my only connection with Mary Riter Hamilton until I read No Mans Land: The Life and Art of Mary Riter Hamilton, by Kathryn A. Young and Sarah M. McKinnon. Thanks to their exhaustive research, I now have a well-rounded picture of the life of a prolific artist.

Mary Riter was born in Ontario in 1868 and moved with her family to Manitoba when she was a teenager. Mary found work as an apprentice milliner. When her employer transferred to Port Arthur, Ontario, Mary went with her. In Port Arthur she met Charles Hamilton, who owned a dry goods store. In 1889, Mary became both his wife and business partner. During the next four years, Mary lost a child, and her husband died suddenly, leaving her a sizeable inheritance. Mary’s lack of family responsibility and her financial stability allowed her to pursue her artistic talents.

Mary moved to Winnipeg and opened a studio, where she taught and did her own work. She traveled to Toronto to study and successfully entered her paintings in contests and exhibitions. In 1901, Mary set off for Europe and spent the next decade studying there. Her work was exhibited in the Salons of Paris and was well received. In 1911, Mary returned to Winnipeg, and subsequently moved to Victoria, British Columbia. Over the next eight years, Mary did very well—teaching, exhibiting, making connections with influential people, and garnering lucrative financial remuneration for painting portraits. She was awarded impressive commissions.

Then, in 1919, at age 50, Mary decided to go back to Europe to paint abandoned World War I battlefields. Mary would create more than three hundred artworks in Belgium and France during the next six years. But she lived in deplorable conditions in these ‘no man’s land’ spaces. She often went hungry, and she suffered from serious health problems.

When Mary returned to Canada in 1925, she faced many obstacles trying to get her war paintings exhibited. In 1926, she donated them all to the Canadian Archives. The last twenty-five years of Mary’s life were marked by lost friendships, time spent in and out of psychiatric hospitals, and financial instability. She died in Vancouver in 1954.

The key question this book poses is what drove Mary to leave her safe comfortable life and thriving career to do war paintings and endure the hardships of post-war battlegrounds? Perhaps a clue can be found in a quote that introduces the book’s second chapter. It is from a newspaper interview that Mary gave in Winnipeg in 1906, after an exhibit of her work had been very favorably received. Mary said, “Of course I haven’t done anything yet, but I hope I shall some day.” Her words seem self-deprecating, considering that Mary had already taught countless art students, exhibited her work throughout Canada, and won prestigious prizes. She had even had an art piece featured on the cover of a French magazine.

Did she feel these accomplishments weren’t worthwhile? McKinnon and Young title the chapter about her battlefield painting years, “Art With a Purpose,” and explore why Mary felt her war paintings were more important than any of her previous work.

No Man’s Land is meticulously researched, with bibliography, notes, index, and appendix taking up nearly half its pages. Its scholarly integrity does not detract, however, from the engaging portrait of Mary the book provides. I am a fiction writer, and as I read this book, I considered what great short stories various episodes of Mary’s colorful life might inspire. The book includes a selection of artworks by Mary and a number of photographs of her. In some photos the marvelous hats that Mary and her friends wear pay tribute to Mary’s first job as a millinery designer.

The title of the book, No Man’s Land, was also the name of an exhibit of Mary’s work mounted in 1989 by author Sarah McKinnon when she was the University of Winnipeg art curator. Sarah worked on the exhibit with Angela Davis, a University of Manitoba graduate student who had written an essay for the Manitoba Historical Society about Mary Riter Hamilton. Sarah McKinnon and Kathryn Young have dedicated their book to Angela, who died in 1994.

Mary Riter Hamilton’s Easter Morning is in the permanent collection at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. It is a charming painting, but I have to admit that it wasn’t one of the artworks I usually stopped at as I toured visitors through the gallery. Now I will. That is not only because, thanks to this book, I will be able to tell them a great deal about its artist, but also because I now know what an important role Mary played in the opening of the gallery where her painting hangs. In 1906, Mary briefly returned from Europe for a Winnipeg exhibition. Journalists used Mary’s work as an example of how the arts might enrich citizens’ lives, and exhorted readers to consider opening a city art gallery. In May of 1912, Mary mounted another Winnipeg exhibit and, in press interviews, insisted it was time Winnipeg had an art gallery. In December of 1912, the Winnipeg Art Gallery opened.

Although Mary lived in Winnipeg for only brief periods during her life, she made a lasting contribution to the city’s artistic heritage.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 31 March 2021