by Christy M. Henry

S. J. McKee Archives, Brandon University

|

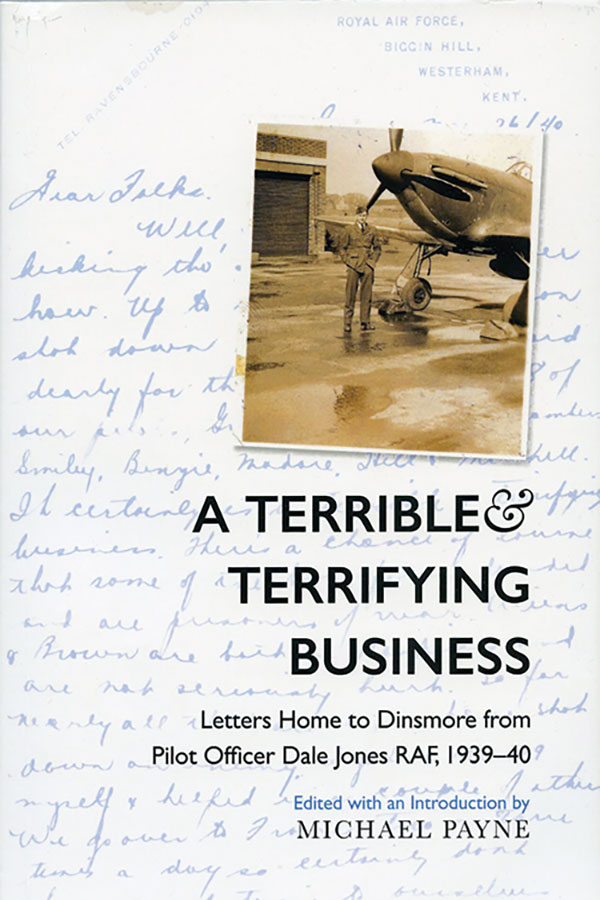

Michael Payne (ed.), A Terrible & Terrifying Business: Letters Home to Dinsmore from Pilot Officer Dale Jones RAF, 1939–40. Ottawa: YF Historical Research, 2016, 215 pages. ISBN 978-1-55383-425-0, $25.00 (paperback)

Michael Payne’s A Terrible & Terrifying Business presents a collection of letters by Pilot Officer Dale Jones (RAF 42131) sent home to his family in Dinsmore, Saskatchewan between 1939 and 1940. Written to both his parents, with asides to his two brothers, as well as his sister and her husband, the letters chronical Dale’s life from the time he applied to join the RAF in Canada, through his flight training and subsequent as-signment to 242 Squadron, the RAF’s “All-Canadian” squadron. It concludes with his death, fighting over Dunkirk in May 1940. The book would appeal to those interested in military and aviation history, as well as those interested in public and local history, particularly those with a connection to the Dinsmore area.

Michael Payne’s A Terrible & Terrifying Business presents a collection of letters by Pilot Officer Dale Jones (RAF 42131) sent home to his family in Dinsmore, Saskatchewan between 1939 and 1940. Written to both his parents, with asides to his two brothers, as well as his sister and her husband, the letters chronical Dale’s life from the time he applied to join the RAF in Canada, through his flight training and subsequent as-signment to 242 Squadron, the RAF’s “All-Canadian” squadron. It concludes with his death, fighting over Dunkirk in May 1940. The book would appeal to those interested in military and aviation history, as well as those interested in public and local history, particularly those with a connection to the Dinsmore area.

The letters are part of a larger archival collection held by the Saskatchewan Archives Board. The collection, which consists of correspondence, photographs, newspaper clippings and articles were saved by members of Dale’s immediate family and passed down to successive generations. The correspondence includes letters by Dale, letters by his parents that were returned after his death, and letters to his parents from fellow pilots. The photographs and clippings were collected in scrapbooks to document Dale and his fellow pilots in 242 Squadron.

Payne explicitly states that the letters offer no insight into the mechanics or strategies of war or the creation of 242 as an “all-Canadian Squadron,” which are the usual topics of military historians. Rather, he writes, “the material offers valuable information on the RAF’s recruitment and training of pilots from Canada, the attitudes of young RAF pilots to the war effort and their place in it, and the lives of these pilots when not engaged in combat .... Even more poignantly they reveal just how strong a hold home and the lives of the people left behind exerted on these young men” (p. 2).

It is hard to argue that Payne fails in his intended purpose of making the public aware of Dale’s letters. Nor can one argue that he misrepresents the value of those letters; the letters contain no grand revelations or insight about the war itself or the 242 Squadron. Instead, they represent one man’s experience as an RAF pilot leading up to and during the early part of the Second World War, exactly as Payne outlines in the early part of the book. Similarly, it is difficult to criticize the content of the letters themselves. Perhaps what can be argued is that, as one reads the book there is a growing sense of an opportunity missed by Payne. By choosing, not to engage in any significant analysis of the letters, and by instead presenting the letters ‘as is’ with minimal contextualization, he has left a part of the story unfinished.

An example of the letters sent by Dale Jones to his family.

The book is divided into roughly four parts. The introductory chapters provide helpful context for the letters themselves, both in terms of providing background information on RAF recruitment and training, as well as the history of 242 Squadron. Payne is explicit in stating that this information is only a brief and general overview, and it is sufficient for its purpose: the primary and secondary sources referenced in the footnotes provide the reader with further avenues to explore if they are so inclined, as well as additional information on people and events touched on in the letters. The introduction also highlights what Payne believes is the value of the letters. He does not make grandiose claims that the book cannot live up to. In reality, in its lack of detail or depth, the book is a supplementary read. Dale’s letters are one small aspect of a much larger topic, and as such, the book is most valuable as a text to flesh out the more formal record, or to add the human element to drier military and political analysis.

Dale’s letters, which make up the bulk of the book, are reproduced with only minor edits, a deliberate choice on Payne’s part in order to “allow Dale’s voice to be heard as clearly as possible” (p. 23). Dale is a competent writer, and though the letters contain little insight into his inner emotions, they do speak to his thoughts and impressions of RAF training, the war, and his fellow pilots. They also speak to his continued connection to and yearning for home. The appendices, which contain additional archival materials that touch on Dale’s death and the history of 242 Squadron, provide some closure, but Payne does a poor job drawing direct links between some of the information and Dale’s letters. The inclusion of a map showing the numerous locations mentioned in Dale’s letters would have also been helpful to give the reader a firmer grasp of Dale’s movements and activities.

The framework of the book is largely successful in presenting the materials in a clear and organized manner, but the lack of a conclusion or any kind of summary analysis of Dale’s letters in a broader context is frustrating. The decision to present the letters ‘as is’ in order to allow the reader to experience them as archival sources is fine, and in some ways allows the reader to form opinions and interpretations on their own, but without a substantial conclusion the story feels unfinished. The closest Payne comes to any analysis is in Appendix B when he investigates the validity of the recollections of Dale’s death by one of his fellow pilots.

Early in the book, Payne makes note of how Dale’s service and death had a significant impact on his family, and yet he provides little evidence of this aside from the family’s decision to keep Dale’s letters and compile scrapbooks about his military experience and death. There are no letters from Dale’s family members included in the book; Payne makes the decision not to include the letters Dale’s parents wrote to him after his death, reasoning that the letters make for difficult reading. While this may be true, excluding them is just another way that the story remains unfinished. Again, the footnotes provide some context and colour to Dale’s letters, but they also highlight the lack of information about Dale’s family. More information on what was happening to the family beyond Dale’s own brief references, would have rounded out Dale’s letters and feelings. Similarly, knowing more about Dale’s life prior to his decision to join the RAF would have grounded his decisions and feelings about his experience more firmly. Despite some small hints as to the family’s activities, the lack of family history or an exploration of additional existing family records compounds the feeling that Dale’s letters and the book itself are only a partial picture.

One cannot help but ask some additional questions about selection. Because Payne seems to have decided to present the materials in a passive manner, the reader is left wondering why these letters? Is it simply because they were available for publication? Is it because Payne has a particular interest in or connection to the specific subject matter—the history of Saskatchewan or aviation, the RAF or military history? To take it a step further, what was Payne’s reasoning for the including specific photos and clippings from the Jones family scrapbooks alongside certain text? In his biographical blurb on the back of the book, Payne is described as a part-time freelance historian and editor on projects “that help make archival materials more accessible to the reading public.” So if his interest is the promotion of archives, how do the photos and clippings—i.e., the visual component of the archival collection—help advance and support the content of the textual records? These criticisms stem from the missing description of the motivation behind Payne’s decisions. By largely choosing not to discuss his choices related to the records and their publication, Payne leaves the entire project unmoored. While he may have had no intention in engaging in an analysis of Dale’s letters or tying them to the larger body of scholarship, there was, nevertheless, a squandered chance to explore Dale’s experience in a greater context.

As mentioned, the value of Payne’s A Terrible & Terrifying Business is that it sheds light on one man’s wartime experience. Dale’s story is both unique to him, and yet all too familiar to so many other men and their families who wrote similar letters during the same period. In this way, Dale’s letters speak to both the common and specific experience of the war and, as such, they are a worthwhile resource and worth Payne’s efforts in bringing them to the public’s attention. That said, although Payne provides additional primary and secondary sources to complement Dale’s story, the lack of a conclusion or any substantial analysis of the material is a missed opportunity. The failures of the book lie not in the execution of the author’s original intent but rather in the lack of ambition in that intent.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 26 November 2020