by Paul Esau

University of Lethbridge

|

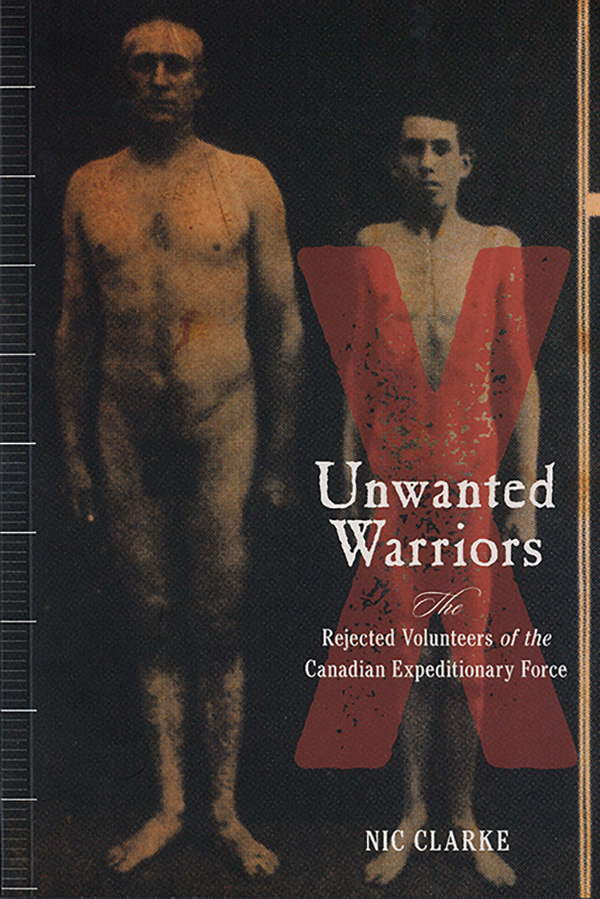

Nic Clarke, Unwanted Warriors: The Rejected Volunteers of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2015, 256 pp. ISBN 9780774828888, $29.95 (paperback)

What does an ideal soldier look like in the public imagination? What are the actual minimum physical requirements necessary for an effective soldier? These two questions have concerned many societies and many militaries, and they provide the competing concepts of appearance and function which clash in the heroic über-mensch of the recruiting poster and the decidedly less glamorous reality of military medical examinations. What a society expects its warriors to embody, and what physical attributes a military requires its recruits to possess are interconnected and yet distinct structures.

What does an ideal soldier look like in the public imagination? What are the actual minimum physical requirements necessary for an effective soldier? These two questions have concerned many societies and many militaries, and they provide the competing concepts of appearance and function which clash in the heroic über-mensch of the recruiting poster and the decidedly less glamorous reality of military medical examinations. What a society expects its warriors to embody, and what physical attributes a military requires its recruits to possess are interconnected and yet distinct structures.

Canadian War Museum historian Nic Clarke’s most recent work, Unwanted Warriors, explores this tension of expectation and function in the context of Canadian recruitment during the Great War. Clarke estimates that between 1914 and 1918, between 100,000 and 200,000 Canadian men were rejected as unfit for service in the CEF. Considering that Canada’s pre-war population was only seven million, this means a significant minority were forced to deal with the trauma of being labelled ‘unfit’ in a society that viewed disability as emasculating and even threatening. By analyzing the personnel files of 3,400 Canadian recruits deemed unfit for service either at Canada’s primary training camp at Valcartier, Quebec in 1914 or after having arrived in England, Clarke is able to build both an intimate understanding of the criteria of the medical examination itself, as well as the consequences of medical rejection upon the public and private lives of these men.

Clarke dedicates the first four of the book’s seven chapters to the evolving process of determining and implementing the physical standards which functioned as the basis of the Canadian military’s wartime medical examination. Although it is the rejected volunteers who are the explicit subject of the book, it is the mechanism and evolution of the medical examination itself which Clarke explores in the greatest detail. This is partly a practical concession—since it is only by successfully navigating several medical examinations that a recruit could become a true member of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF)—and partly a result of the ideological (rather than explicitly functional) foundations for many of the mandatory physical requirements evaluated by the exam. As the Canadian army’s understanding of and requirements for the Great War evolved, so too did the requirements for the Canadian recruit.

For example, Clarke stresses the transition from a dichotomous model in 1914 that classified recruits as simply ‘fit’ or ‘unfit’ to the hierarchical model of 1918 which recognized multiple levels of ability for different kinds of military service. Just as the militaries of the Great War had struggled to adapt to the new realities of industrial warfare, with its complex logistical and support requirements, so too Canadian medical examinations evolved to recognize that not all recruits needed to be capable of front-line combat. This “A-D” ranking system, first implemented in rudimentary form in 1916, gave medical examiners the flexibility to identify recruits’ potential ability rather than immediately disqualifying them based upon inability. As Clarke notes, “The victories at Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele and during the Hundred Days were achieved with many men who would have been rejected as unfit to serve in 1914”(p. 9).

Clarke also documents an overall decrease in physical requirements for Canadian recruits; a result, he argues, both of changing perceptions of fitness and the increasing manpower needed to meet promised expansions in the size of the CEF. Before the onset of hostilities in 1914, Canadian infantry had to be at least 5 feet 4 inches tall, demonstrate an expanded chest circumference of 34 inches, and have no reliance upon either dentures or glasses. By 1917, infantry height requirements had been reduced to five feet (although other branches had stricter requirements), and regulations allowed the use of glasses and dentures to augment vision and consumption, respectively. The latter two changes in particular had a pronounced effect upon the size of Canada’s recruiting pool, since 34 percent of Clarke’s 3,400-strong sample group from 1914 were rejected for either substandard eyesight (24 percent), or poor teeth (10 percent). Both the vision requirements and dental requirements were pilloried by civilian critics and rejected volunteers alike as being irrelevant to the business of war. In the words of an angry Scottish Canadian recruit appearing in a 1914 Punch cartoon, “I dinna want tae bite the Germans; I’m offerin’ tae shoot them”(p. 81).

The next most abundant reasons for rejection—varicose veins (7 percent), and varicocele (6 percent)—were also grounds for contention according to Clarke, illustrating how the ambiguity of medical requirements could leave the medical examiner considerable leeway to use his own discretion to evaluate recruits. Canadian recruiting regulations into 1917 stated that individuals with ‘marked’ varicocele were to be rejected, yet gave no description of how ‘marked’ the condition had to be before it became grounds for rejection. The examiner was also required to subjectively evaluate a recruit’s age and intelligence during the examination. Unwanted Warriors consequently shows that the evolution of Canadian medical examinations during the Great War was also a struggle to standardize and demystify the amorphous concept of the acceptable Canadian soldier.

In the last three chapters, Clarke explores the socio-psychological costs incurred by those men rejected for medical reasons, and their collective attempts to navigate those costs. As with any imaginary community, the handsome, masculine ‘soldier’ archetype of the Great War was partially defined by its opposite: the degenerate, perhaps ‘scrofular’, shirker. The glorification of the former led, by direct consequence, to the condemnation of the latter; a condemnation that was tangibly expressed in the confrontation of suspected shirkers by the recruiting officer and by the overeager patriot in the streets of Canadian cities. Clarke explains that since society evaluated potential recruits primarily on their visual characteristics, and since the most common reasons for medical rejection (poor vision, bad teeth, or circulatory conditions) were not visible, rejected volunteers were often lumped into the category of shirker despite their attempts to serve their country. Clarke documents several extreme cases where men killed themselves rather than live with the shame of having been rejected, and makes some preliminary connections between the popularity of eugenics ideas in early 20th-century Canada and the perception of the medically unfit as a burden to their nation. In this rather stark Darwinian sense, Clarke argues that to be declared unfit “was a direct assault on one’s self-worth, honour, and masculinity” (p. 119).

To combat these accusations, many rejected volunteers sought to differentiate themselves from shirkers by stressing that they had attempted to serve their country. In 1916, the Dominion government created a three-tier system of war service badges to help returning veterans or those rejected for service identify themselves to recruiters and the general public. Clarke argues that these decorations could be seen as either a badge of honour or a mark of shame, and were not entirely embraced by those rejected for medical reasons. Still, the formation in 1918 of the Honourably Rejected Volunteers of Canada Association proves that a significant number of rejected volunteers saw their status as potentially important, both for redeeming their place in a post-war society, and in gaining access to at least some of the government-mandated benefits enjoyed by returning veterans.

Clarke devotes his last chapter to those who actively pursued a qualification of medically unfit as a way to avoid donning the khaki while still maintaining an ‘honourable’ veneer. He highlights the numerous ways in which men sought to manipulate the system by feigning various ailments (often short-sightedness), or how civilians (generally women) could use accounts of their own illness or distress to have family members released from service. In this way the ‘casualties’ of the system could also find ways to empower themselves and manipulate their circumstances for personal advantage.

Unwanted Warriors is in many ways an exploration into a new theatre, and Clarke is conscientious in limiting the scope of his work to the concrete bones of both the examination itself and the testimony of the rejected recruits. Clarke weaves in the occasional popular source in the form of Punch cartoons, period literature, and even newspaper advertisements, serving as splashes of colour against the central analysis of Clarke’s 3,400 medical records augmented by subsidiary documents and personal letters. It is obvious that Clarke intends his work to be a foundation for more comprehensive research, since he nods to the influence of early 20th-century concepts of masculinity, disability, and nationhood upon these ‘unwanted warriors,’ without attempting to systematically elaborate upon said connections. In this Clarke is very much a military historian, and it will be left to the anthropologist and sociologist (among others) to fully explore this further.

Still, Unwanted Warriors is a well-researched and novel contribution to the history of Canada’s participation in the Great War. It provides a solid foundation for new research possibilities, and highlights a Canadian community which has long been confined to the historical sideline. Ultimately, Clarke’s workdescribes both the actions of these rejected volunteers and the evolution of the medical examination itself as attempts to redefine the concept of disability, and, in so doing, better reflect the needs of the Canadian military as well as the social value of those declared ‘unfit’.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 8 November 2020