by Dianne Dodd

Historian, Parks Canada

|

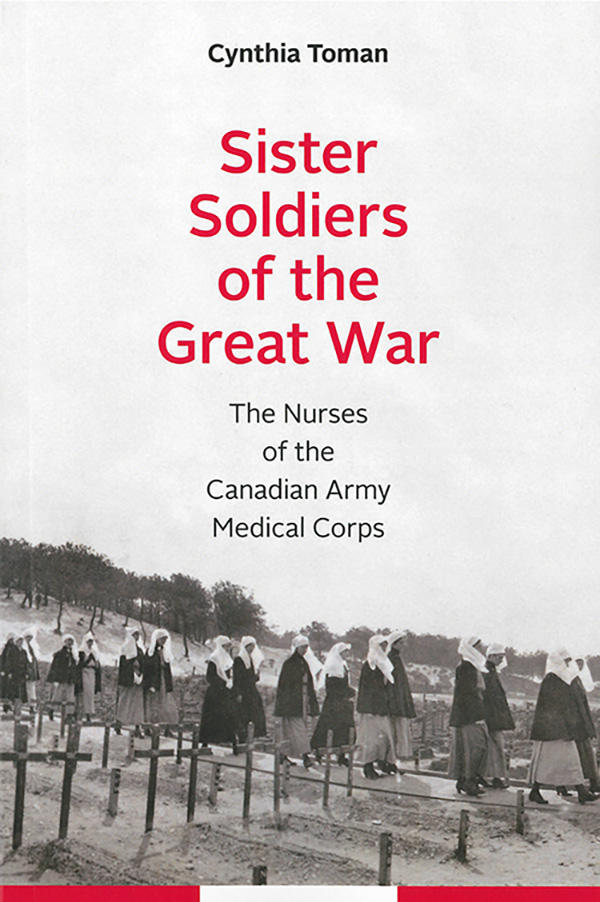

Cynthia Toman, Sister Soldiers of the Great War: The Nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2016, 312 pp. ISBN 9780774832144, $34.95 (paperback)

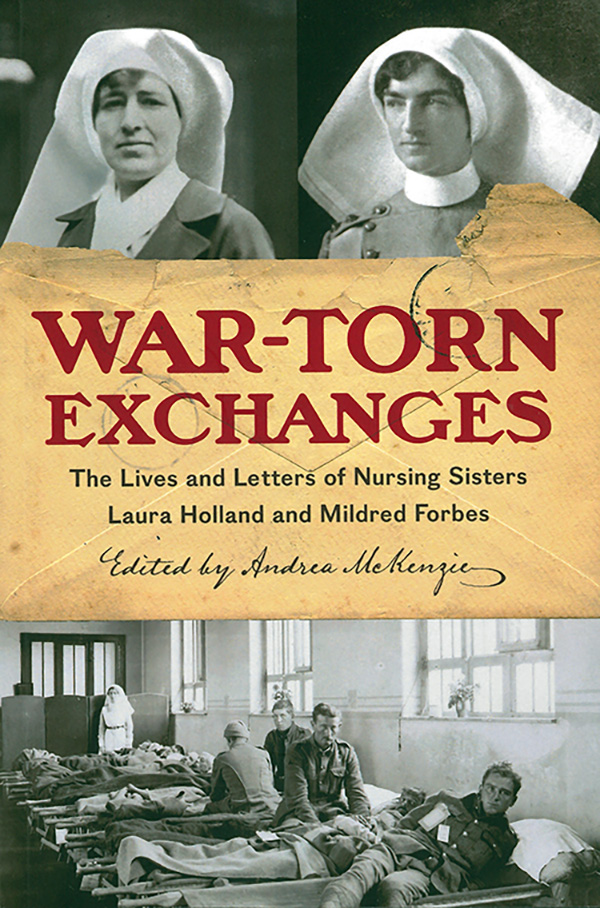

Andrea McKenzie (ed.), War-Torn Exchanges: The Lives and Letters of Nursing Sisters Laura Holland and Mildred Forbes, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2016, 268 pp. ISBN 9780774832540, $32.95 (paperback)

These two books from the University of British Columbia Press add immeasurably to the growing historiography on Canadian military nursing in the First World War, helping us to better understand not only nursing history and women’s history, but the military medical system in which nurses played an integral role.

These two books from the University of British Columbia Press add immeasurably to the growing historiography on Canadian military nursing in the First World War, helping us to better understand not only nursing history and women’s history, but the military medical system in which nurses played an integral role.

Toman’s comprehensive analysis uses qualitative and quantitative sources to move the field beyond the sometimes hagiographic approach of popular histories. Considering the few nurses whose stories have survived, Toman presents an impressive number of short biographical sketches. These, along with a demographic profile of the first women to serve in the Canadian military, reveal a great diversity of backgrounds. Sister Soldiers, through a painstaking analysis of attestation papers and military personnel files on all the nurses, also revises the long repeated estimate that there were 3,141 Canadian Nursing Sisters serving in the Canadian Armed Medical Corps. Eliminating duplications and errors, Toman corrects that number to 2,845, of which, interestingly, only 2,816 were actually trained nurses: apparently Matron-in-Chief Margaret Macdonald was not able to completely resist political pressures to take on non-nurses. Thus, included among the Nursing Sisters (a women-only title), were housekeepers, female physicians, and even a few wives of officers.

Building on some of her earlier work, which demonstrated that nurses identified as ‘soldiers’ and rejected the ‘ministering angel’ stereotype, Toman presents nurses as military personnel first and foremost. Even when working under harsh conditions—as in the Mediterranean where food and water were scarce, heat was oppressive, and dysentery, malaria, and other tropical diseases took a heavy toll—nurses were determined to stay as long as they were needed. In a chapter on sociability, Toman does not shy away from examining nurses’ relationships with others, providing a portrait of nurses’ social lives and friendships, including the travels they undertook during slow times, on leaves, or while waiting for reassignment. Medical officers, who often acted as ‘superiors’ (as they did in civilian hospitals), were members of a previously all-male military system, and were not always sure how their new female colleagues would fit in. Still, they functioned as friends, colleagues and fellow officers. Toman also sheds light on the role of orderlies, a hitherto shadowy force in the medical system. Orderlies were often older soldiers who were unable to do active service. They outnumbered nurses two or three to one, and did much of the grunt-work in the hospital wards. Often coming under the nurses’ authority, and/or receiving training from them, their resentment sometimes emerged. While the antagonism of British nurses—who persisted in treating Canadian Nursing Sisters as ‘colonials’—is well documented in the literature, this nurse orderly dynamic is part of the story hitherto ignored in the historiography.

Building on some of her earlier work, which demonstrated that nurses identified as ‘soldiers’ and rejected the ‘ministering angel’ stereotype, Toman presents nurses as military personnel first and foremost. Even when working under harsh conditions—as in the Mediterranean where food and water were scarce, heat was oppressive, and dysentery, malaria, and other tropical diseases took a heavy toll—nurses were determined to stay as long as they were needed. In a chapter on sociability, Toman does not shy away from examining nurses’ relationships with others, providing a portrait of nurses’ social lives and friendships, including the travels they undertook during slow times, on leaves, or while waiting for reassignment. Medical officers, who often acted as ‘superiors’ (as they did in civilian hospitals), were members of a previously all-male military system, and were not always sure how their new female colleagues would fit in. Still, they functioned as friends, colleagues and fellow officers. Toman also sheds light on the role of orderlies, a hitherto shadowy force in the medical system. Orderlies were often older soldiers who were unable to do active service. They outnumbered nurses two or three to one, and did much of the grunt-work in the hospital wards. Often coming under the nurses’ authority, and/or receiving training from them, their resentment sometimes emerged. While the antagonism of British nurses—who persisted in treating Canadian Nursing Sisters as ‘colonials’—is well documented in the literature, this nurse orderly dynamic is part of the story hitherto ignored in the historiography.

At the practical level, readers will learn details of nurses’ work in support of the Canadian Armed Medical Corps during the war, an element that is often missing because nurse memoires were more likely to comment on the nonroutine than the routine. Sister Soldiers provides a helpful ‘roadmap’ of the military medical system, showing readers where nurses could and couldn’t serve, and what kinds of work they did, both medical and surgical. Toman does this expertly, as only a former nurse can, and in this sense Sister Soldiers is an excellent complement to her earlier book on the nurses of the Second World War, An Officer and a Lady (UBC Press, 2007).

Toman’s Sister Soldiers quietly adds to the debate on the impact of the war on women, at least as it pertains to nurses. She approaches the subject of postwar experiences for nurses, many of whom tried to maintain their military connections by serving for as long as they could in Canadian hospitals for convalescent soldiers, though, sadly, most of these jobs were short-lived. Toman demonstrates that many nurses, despite their dedication to empire and the war effort, came to question the costs of war after it was over.

Some historians have linked postwar work and professional gains and even women’s victory in the long suffrage battle to women’s wartime ‘contributions.’ Others contend that the war left gender roles unchanged. Because nurses were perceived as being at the pinnacle of women’s war work, their experiences shed light on this question. Nurses were certainly proud of their place in the military, believing that they were paving the way for professional women in the military, and enhancing the standing of nursing as a profession. Much has been made of Canada’s Nursing Sisters being the first nurses, and hence the first women—not just in Canada but among western allies—to hold rank as officers in the military. Putting this in context, Toman explains that the military’s motivation in granting rank was to keep these women firmly under military control, and that their relative rank gave Nursing Sisters only limited authority within the hospital. And, like other women after the war, most nurses were dismissed after demobilization. Despite these caveats, Toman shows that nurses held a certain agency within their caregiving role within the military. And in the larger sphere, they also took political roles. For example, Nursing Sister Rachel McAdams, a trained dietician, ran for and won political office in the Alberta legislature during the war.

Complementing Toman’s book in a comprehensive but very different and more personal way, War Torn Exchanges is the wonderful, rich cache of letters written by two nursing sisters and close friends, Laura Holland and Mildred Forbes, and edited by Andrea McKenzie. Holland wrote primarily to her mother, while Forbes wrote to her childhood friend, Cairine Wilson, who would later become the first female Senator in Canada. These letters take us from 1915 to the end of the war. These remarkable, candid letters illustrate the effect of wartime conditions on two women in their early thirties, revealing much about their relationships with each other, and with their colleagues. Holland and Forbes served first in Lemnos, Greece, an island near the coast of present day Turkey, where the conditions were so dismal that they threatened nurses’ cohesion as a group, although not their resolve to continue serving. The hardships of these postings have long been known, but here we get a first-hand view of the daily effects of dire shortages and poor administration. With so little food available, a Nursing Matron’s leadership was judged, fairly or not, on how good she was at procuring food from local sources. Water shortages are brought to life in descriptions of nurses working for months without being able to wash their hair or take a bath, and in the demoralizing impact on them trying to take care of fevered dysentery patients. Holland in particular expresses her frustrations with the military hierarchy, which she blamed for much of these hardships. Such conditions took their toll on all military personnel, and we see the personal impact of the first nurses’ deaths from the vantage point of these two women. Both Forbes and Holland had varying degrees of dysentery in their first assignment, caring for each other as they best they could. Officers and orderlies, like nurses, also took sick.

After surviving Lemnos, the two nurses travelled to Cairo where they went sightseeing while waiting to be reassigned. From there, they travelled to Salonika, on the Greek mainland, where heat and malaria were their greatest enemies: Forbes was struck with malaria, and Holland described days in which the temperature rose to as high as 107 degrees Fahrenheit. Cooler nights brought respite, but when medical staff worked on night duty it was nearly impossible to sleep during the day, as tents, set up on a plain with little shade, became blistering hot. At both these postings, the two nurses were disappointed to be treating only the moderately ill, rather than more critical injury cases, as would have been the case in France.

These letters are also testament to the support these nurses got from home, as family and friends sent many gifts, often by raising money in their home communities. They sent treats, usually for the soldiers, but also included necessities (and treats such as Christmas cake) for the nurses. The letters reinforce other sources in suggesting that nurses usually put the soldiers ahead of themselves. The letters also reveal the impact of military censorship, and the ingenious ways in which personnel circumnavigated it, whenever they could. Maintaining the communications link with home was absolutely essential for morale. But serving overseas certainly did not free nurses from sharing worries about loved ones left at home. Rather, it added a greater measure of responsibility. For instance, when Holland’s nephew went missing, it caused great anxiety, and she and Forbes used their inside connections to gain information. When they eventually learned that the missing airman had been taken prisoner of war, the family was relieved for the news.

Next, the women travelled to Britain where Forbes was recalled to serve as Matron-in-Chief Margaret Macdonald’s assistant through a particularly difficult time. A political controversy over the use of Canadian medical personnel in support of British (rather than Canadian) troops had caused a major upheaval in CAMC’s administration. Holland nursed at No. 1 Hyde Park Place, a Canadian hospital for officers where she enjoyed a much more comfortable life than at Lemnos and Salonika. Forbes was a personal friend of Matron-in-Chief, and that friendship brought perks. Holland and Forbes were often entertained by Macdonald and her high ranking friends. More importantly, it also helped ensure that she and Holland could avoid separation during the war, a possibility that caused them some considerable anxiety. Holland even turned down promotions to stay with her friend and the two often combined their individual living spaces into one, to make it as a ‘home’ for themselves. Macdonald accepted the importance of female-based support networks and understood their need to be together, assigning them to the same place throughout the war. While she was in England, Holland learned that she, along with most of the nurses who had suffered through the horrors of Lemnos, would be accorded a Royal Red Cross, 2nd class. Although she was very proud to attend the ceremony at Buckingham Palace and to meet Queen Alexandra, Holland could not quite forgive Macdonald for not letting her share this special moment with her friend, Forbes. It appears that Macdonald was trying to avoid charges of favouritism toward her new assistant, and recommended Forbes for a medal later on during the war.

And finally, the nurses were moved to Casualty Clearing Station 2, near Ypres in France. Here, they would finally be plunged into the front line of nursing work. Casualty Clearing Stations were the closest nurses got to the front, and as CCS2 was such a busy one, it was a much coveted placement. Forbes and Holland arrived in mid-July 1917, just as the Third Battle of Ypres, Passchendaele got underway. Unlike Lemnos and Salonika where all the patients were medical, nurses here dealt with thousands of severely wounded and gassed soldiers. In what can only be described as assembly line medicine, the nurses cared for patients who had to be treated quickly, and then either returned to the front or moved further down the line to a general or stationary hospital, usually within 24 to 48 hours. To get an indication of the intensity of the work, this clearing station admitted 3,396 patients during the month of July 1917, and in a scant five days, from July 31 to August 4, they admitted 3,566. Although by war’s end Casualty Clearing Stations were becoming larger, the medical workforce averaged approximately thirteen to twenty four medical officers, twenty nurses and various orderlies. Forbes and Holland, along with their colleagues, would have worked flat out, with little sleep, as casualties arrived by motor and by trains. Sometimes patients lay on stretchers which overflowed the station, and some patients were left outside, even in the rain, until someone could see them. Holland and Forbes were not demobilized until the spring of 1919, and, before coming home, they cared for many victims of the Spanish influenza pandemic.

After surviving all that they saw and experienced, nurses, like soldiers, were changed persons. Echoing Toman’s observations of the group of nurses as a whole, the suffering these two nurses witnessed led to a certain disillusionment with the ‘costs’ of war. Illness also took its toll, especially on Forbes, but Holland went on to have a successful postwar career in which she combined nursing with social work, a decision that is foreshadowed in Holland’s wartime observations of gender and class inequalities in the military system.

Both of these books are eminently readable and provide an excellent window into nurses’ experience during the First World War—from clinical, military, and social perspectives. These books help us to understand who these people were, what they did within the military medical system of the First World War, and what it cost them.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 9 November 2020