by Andris Straumanis

Department of Communication and Media Studies,

University of Wisconsin-River Falls

|

|

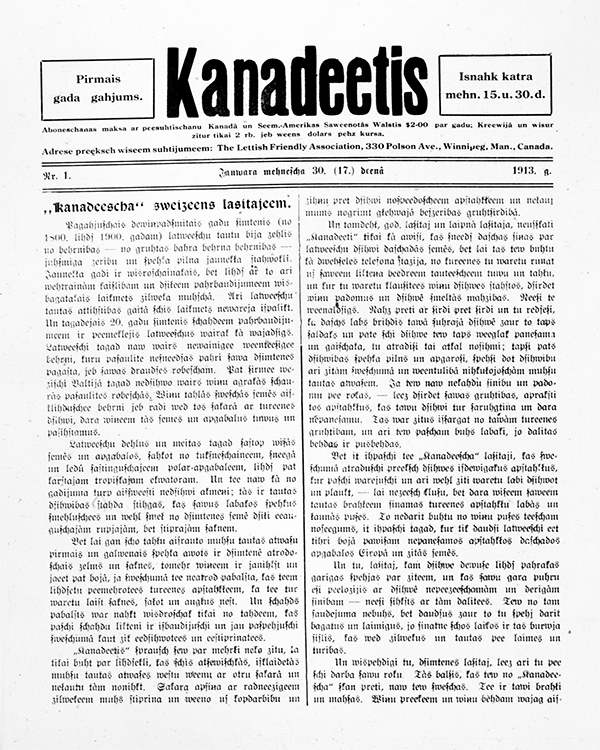

Front page of the first issue of Kanādietis (The Canadian), published in Winnipeg from January 1913 to July 1914. |

The first edition of Kanādietis [1] (The Canadian) promised much. A small, semi-monthly Latvian newspaper published in Winnipeg but meant for immigrants throughout North America, Kanādietis was an alternative voice to the sometimes shrill calls of the dialectically opposed radical socialist and Christian-nationalist press to which readers had become accustomed in the first decade of the 20th century. [2] The first issue, dated 30 January 1913, even ran advertisements from the two leading newspapers for North American Latvians—the increasingly radical socialist Strādnieks (The Worker) and the Christian-nationalist Amerikas Vēstnesis (America’s Herald)—suggesting that the Canadian paper and its editor harboured no ideological predisposition. However, the paper failed in its efforts to reconcile socialists and non-socialists and by the end of the year Kanādietis was forced to suspend publication, its editor hoping that economic hard times in Canada would improve enough to allow continuation. Only one more issue was published, in July 1914, and any promise for the future was cut short by the First World War.

The newspaper’s 23 issues, [3] besides providing a brief record of Latvian immigrant life in the western provinces of Canada, serve as source material for a case study of the role of the North American immigrant press. Beginning with the work of Robert Ezra Park in the 1920s, scholars of the immigrant press have debated whether the institution serves more to maintain ties with the homeland or to encourage integration into the host society. More recent scholarship suggests that the immigrant press serves a dual—and multi-dimensional—role, striking “a balance of assimilationist-pluralist functions”, according to scholar Stephen Harold Riggins. [4]

This article identifies the broad discursive themes that related to how the producers and consumers of Kanādietis might have used the newspaper so that—as communications scholar James Carey described the process—they might understand the ritual order of their society. [5] Carey argued that the process of communication can be viewed both as the transmission of news and knowledge and as a ritual likened to a religious service, “a situation in which nothing new is learned but in which a particular view of the world is portrayed and confirmed.” [6] Ritual also is part of a transformative process, as anthropologists Arnold van Gennep, and later Victor Turner, suggested. Van Gennep in his 1908 book, The Rites of Passage, [7] developed a model of ritual involving three stages: rites of separation, rites of transition (the liminal stage), and rites of incorporation. Van Gennep was concerned especially with how homogeneous or tribal groups use rites such as funerals, marriage, and initiation to make sense of change in social status. Turner expanded on the concept of liminality, seeing it as a liberating phase in the passage of an individual or a group from one social structure or cultural condition to another. [8] In the liminal phase, an individual or group is liberated from the social structure of the previous phase, passing “through a cultural realm that has few or none of the attributes of the past or coming state.” [9] In studies of European immigrant communities in North America, and specifically in research on the immigrant press, an underlying assumption often has been that immigrant communities over time inevitably acculturate—socially, economically, symbolically—from the “Old World” to their new, host society. The pages of Kanādietis reveal a tension between separation and incorporation as editor Jānis A. Šmits and other writers negotiated between nostalgia for their homeland and full absorption into life in a new country, while at the same time expressing desire for a cultural and social space that would allow them to maintain their Latvian identity.

In the history of the Latvian immigrant press in North America, Kanādietis is unusual, largely because it was the only known pre-First World War Latvian language publication in Canada. The newspaper also was notable for its attempt to hold to a middle road in the increasingly acrimonious war of words being waged south of the border, between Christian-nationalist Latvian publications following one path, and socialist publications following another. This article is the first detailed examination of Kanādietis and, as such, is substantially devoted to describing the life of the publication and of its editor. As an attempt to broaden knowledge of the Latvian immigrant press in particular and of European immigrant publications in North America in general, this article also poses several questions that should be considered within the context of the Latvian immigrant experience: Why did such a publication appear in Winnipeg, hundreds of kilometres from the largest North American colonies of Latvian immigrants? As a cultural product, what did the newspaper represent to its readers? Why, ultimately, did the newspaper fail to find a wide audience for its reconciliatory message?

In searching for answers to these questions, the research relied on a close reading of all issues of Kanādietis held by the National Library of Latvia in Rīga and by the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison. (Unfortunately, the pre-First World War Latvian immigrant experience in North America remains poorly documented. Few archival records have been uncovered thus far, and none of the records held by institutions in North America or in Latvia bear directly on Kanādietis. [10])

The migration of ethnic Latvians to North America prior to 1914 has received limited study. The late journalist and amateur scholar Osvalds Akmentiņš was the most prolific researcher, and published much of his work in the post Second World War émigré Latvian press. The research has focussed on the largest and most active urban and rural colonies [11] of pre-war immigrants in Boston; Philadelphia; Lincoln County, Wisconsin; and Alberta. [12]

Latvia, until 1918 part of the Russian empire, had a largely agrarian economy prior to the mid-19th century. Latvians as a class were predominantly peasants serving German barons, whose influence in the region had been established starting with the Christianizing crusades of the Teutonic Knights in the 13th century. Legal reforms during the 19th century eventually freed the Latvians from their subservience to the barons, although the Germans still controlled large tracts of land and held sway over the dominant Lutheran church. During the 1860s—the period of National Awakening—the idea of nationhood began to take hold in the region, fostered by cultural activity such as increased educational opportunities, the flowering of Latvian literature, and interest in Latvian folklore. Concurrent with the rise of nationalism was the industrialization of Latvia, increased migration from rural to urban areas, and growing class-consciousness. [13] The census of 1897 counted a population of about 1.93 million in the four provinces that would become modern Latvia. [14] Like other people in Central and Eastern Europe yearning for a better life, an increasing number of Latvians also began to turn their gaze westward and across the Atlantic Ocean.

Inequities in the socio-economic structure persisted, giving rise in the late 19th century to the leftist Jaunā Strāva (New Current) movement. The Latvian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party, the first Latvian political organization, was established in 1904. In 1905, discontent with working conditions and with land distribution led to a series of labour strikes in the main city of Rīga and bloody uprisings in the countryside. The Revolution of 1905, however, disintegrated by early 1906 and the German barons— against whom much of the rage had been directed— together with the Russian authorities organized punitive military expeditions against the Latvians. Thousands of revolutionaries fled their homeland to Western Europe, the United States, and Canada. Efforts on the part of nationalists to create a Latvian state, and on the part of socialists and communists to realize their ideology in the region, continued through the First World War. In November 1918, the nationalist Latvian People’s Council declared the country independent. Following nearly two more years of fighting Bolshevik and rogue German forces, Latvia in 1920 finally gained its sovereignty.

The arrival in North America of pre-Second World War Latvian immigrants generally is divided into three phases. Regular Latvian immigration to the U.S. and Canada is considered to have begun in the late 1880s and to have continued into the new century. Latvian immigrants of this period came to North America seeking their fortunes, fleeing conscription into the armed forces of the Russian czar, or pursuing religious liberty. Politically, the early immigrants could be divided into two broad groups, reflecting the ideological split in the homeland between the nationalists and the socialists. This division was represented in the first two Latvian newspapers established in America, Amerikas Vēstnesis and Amerikas Latviešu Avīzes (America’s Latvian News). Amerikas Vēstnesis, a nationalist and religious paper published by entrepreneur and community leader Jēkabs Zībergs and Estonian-Latvian Lutheran minister Hans Rebane, appeared in Boston in June 1896. Four months later the liberal Amerikas Latviešu Avīzes began publication, also in Boston. [15]

The second phase of immigration began after the failed 1905 Revolution. Immigrants of this period included many socialists who brought renewed vigour to the Latvian American left, while alienating others with their radical views. One estimate suggests that by around 1906 about 8,000 to 9,000 Latvians were living in the United States. [16]

With the beginning of the First World War, Latvia became a battleground between German and Russian forces. Latvian migration came to a halt until after the 1917 Russian Revolution, when several hundred revolutionary Latvian émigrés returned to their homeland to work for the creation of a Bolshevik government in Latvia as well as in the Soviet Union. A number of nationalist Latvian Americans also repatriated after the country declared independence in 1918.

The third phase of immigration from Latvia began after 1918 and continued as a trickle until the outbreak of the Second World War.

How many ethnic Latvians in all came to North America before the Second World War is difficult to determine. According to figures compiled by Francis J. Brown and Joseph Slabey Roucek and published in 1937, a total of 4,309 Latvians came to the U.S. before 1900, while 15,968 arrived from 1901-1936. [17] Until the 1930 census, the U.S. government lumped Latvians in with Lithuanians or Russians. In 1940, the census counted 34,656 people of Latvian origin, about 54 percent of them foreign-born.

The extension of railways into western Canada to serve the wheat economy and the promotion of settlement spurred rapid migration to the prairie provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. Winnipeg, considered the gateway to these provinces and described in 1909 by the writer Ralph Connor as “the cosmopolitan capital of the last of the Anglo-Saxon Empires” and “Empress of the Prairies,” [18] grew from 7,985 inhabitants in 1881 to 136,035 people in 1911. [19] Boom times in Winnipeg and the western provinces came to a halt soon after when heightened tensions in Europe in 1912 and 1913 led to a decrease in the British investment that had been fuelling the rapid growth. Railroad construction slowed, real estate values dropped, and unemployment rose particularly in cities such as Winnipeg. [20]

Beginning in the late 1880s until the outbreak of the First War, Latvian immigrants were drawn to a number of locations in the prairie provinces. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Latvians could read both glowing reports about opportunity in Canada, and cautionary stories of hard times. In February 1888, for example, the Jelgava-based Latviešu Avīzes reported on two young men who had set off for Manitoba. Wages in the province were good, land could be bought for next to nothing, and the climate was fine, according to the newspaper. At the same time, the newspaper noted that life in “America” (which in a broad sense included the United States and Canada) was far more expensive than in Russia proper, another destination for Latvian emigrants. [21] Another writer told the newspaper that Texas and Manitoba were the two places in America with the best soil, noting that Manitoba even had wine production. [22] A more skeptical note was struck by a Latviešu Avīzes writer in 1912, by which time a number of Latvian families had settled in Winnipeg and elsewhere in the province. “The life of the farmer is sad,” according to the writer, who had spent time as a farmhand in Manitoba. In cold weather the poorly constructed farm houses offered little protection and few of the Latvian farmers had managed to make their fortune. [23]

Some Latvians who migrated to Canada before the First World War came from the United States rather than directly from the Russian Empire, thus joining other immigrants to Canada who saw promise north of the border. [24] A few were secondary migrants from Latvian settlements in southern Brazil, such as five families that in 1910 travelled from Nova Odessa, via Great Britain, to Bird Island in northern Manitoba. [25] Contemporary estimates in the early 20th century put the population of Latvians in Canada at between 1,000 and 2,000 individuals. However, an examination of the 1916 Census of the Prairie Provinces suggests that the number of Latvians in Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan was closer to about 500. [26] The summer before Kanādietis appeared, an estimated 100 Latvians lived in Winnipeg, but by winter many had moved to farms in the Manitoba countryside. [27] The 1921 census identified just 381 individuals in all of Canada who were described as belonging to the Lettish (Latvian) language group. Of those, 150 were born in Canada, six were born in the United States, and 225 were born elsewhere. [28] Five years later, the prairie provinces were home to 661 Latvians. Manitoba alone had 405 Latvians, 85 percent of whom lived in rural areas. In Winnipeg, there were 51 Latvians, 30 of them female. [29]

As in many communities in North America, the Latvians of Manitoba were divided mainly between the secular socialists and the Christian nationalists. In Winnipeg, a chapter of the Latvian Association of the Socialist Party of America was founded in 1909. [30] Given the political course of the American Latvian socialist movement—and of other foreign-language groups—the Winnipeg local was gravitating toward revolutionary socialism, echoing the influence of post-1905 Revolution radical Marxists who gradually were gaining control of the national organization. This certainly was the case of another Latvian socialist club established in rural Lac du Bonnet in early 1914.

The dominant faith of religious Latvians was Lutheranism. Winnipeg had no Latvian Lutheran congregation, although the Estonian-born minister Johann Sillak (1864-1953) attempted to organize one. In fact, few Latvian congregations were formed in Canada before the Second World War, and the very first, the St. Peter congregation at St. Josephsburg, Alberta, lasted only from 1897 to 1905. In Sifton, Manitoba, the Martin Luther congregation was established in September 1900 but also did not last long. By the time Kanādietis appeared at the beginning of 1913, no clergy were regularly tending to Latvian Lutherans in Canada, but in October of that year the Rev. Wilhelm Otto Zahlis arrived in Manitoba to minister for the next four years in several Latvian and German communities. [31] Baptist ministers also tried to spur interest among Manitoba’s Latvians, but with little success. [32]

Despite objections from the socialists about the need for such an organization, the Winnipeg Lettish Friendly Association was founded 21 July 1912. [33] The association’s role was that of a cultural and community organization which, while class-conscious, was not willing to subordinate ethnicity and cultural maintenance to the struggles of labour. According to Akmentiņš, the goal of association was to unite all Latvians, to aid new Latvian immigrants, to furnish members with books and newspapers from the homeland, and to put on various events. The association also organized a choir. One of the association’s main activities—and financial burdens—was publishing Kanādietis.

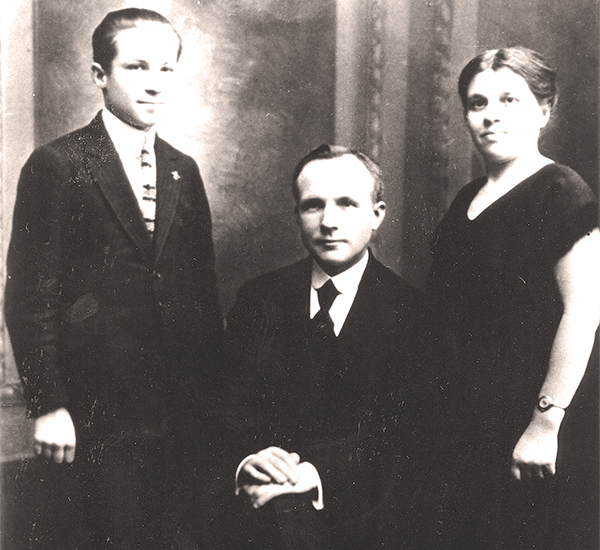

Jānis A. Šmits (1876–1942), centre, editor of Kanādietis with his wife Anna and son Rudolfs, photographed in Riga, Latvia in 1926.

Source: O. Kļaviņš / Viesturs Zariņš

The newspaper’s editor, Jānis A. Šmits (1876–1942), [34] was a man who seemed to embody the ideological struggles of his time. A religious individual, he eschewed the conservative, German-controlled Lutheran church of his homeland, gravitating toward Presbyterianism. At the same time, he was concerned about the plight of the working class, although he could not abide the dogmatism of the radical socialists who would come to dominate the Latvian revolutionary movement.

Šmits was born in Rudbārži in the Kurzeme region of western Latvia. Trained as a teacher in the local parish school, he worked from 1895 to 1905 first at his alma mater and then at schools at Ilmāja, Nīgranda, and Tāši-Padure, all small communities near the town of Aizpute. Caught up in the 1905 Revolution, Šmits like many other Latvians was forced to flee his homeland to avoid punishment and possibly death at the hands of Russian authorities. Manors owned by German barons were frequent arson targets of the revolutionaries. During November and December 1905, more than 400 manors were destroyed, including several around Aizpute. [35] According to his own retelling of events, Šmits was an unwitting participant in the revolution. [36] Asked by a colleague from a neighbouring district to explain how relative calm was maintained where he worked, Šmits one evening found himself leading a debate in Rudbārži between those who were ready to torch the local manor and those who saw nothing to gain from such action. When the manor nonetheless was set afire, fingers pointed to Šmits as the man who had led the fateful meeting where the attack had been discussed. The Russian authorities sentenced Šmits in absentia to death, and he fled to Great Britain. [37]

Like a number of other Latvians in Great Britain at the time, Šmits found work with Vladimir Chertkov, the exiled editor and friend of the great Russian author Leo Tolstoy. At Tuckton along the southern English coast, Chertkov had established the Free Age Press, which published translations of Tolstoy’s work. By the time of the 1911 Census of England and Wales, Šmits, his wife, and son were living in a home on Chertkov’s estate. Chertkov opened the estate to a multi-ethnic menagerie of political ideologies, so that socialists, communists, anarchists and others found a place there, and he helped the Latvian socialists to publish their literature, which was then smuggled into Russia. Šmits, meanwhile, was drawn to religion and may have adopted Presbyterianism while at Tuckton. [38] Chertkov also was a strong supporter of the emigration to Canada of Doukhobors from Russia. [39] This no doubt played a role in Šmits’ own migration to Canada, where he moved his family in 1911 to teach in a Doukhobor colony in Saskatchewan.

From Saskatchewan, Šmits and his family soon relocated to Winnipeg, settling into a house on Polson Avenue in the old North End, a district teeming with East European immigrants. He studied theology and language at the University of Manitoba and also was involved with the British-Canadian Bible Society. In 1912, he helped form the Winnipeg Lettish Friendly Association. By mid-1913, Šmits was serving as manager of the Russian Reading Room in the Robertson Memorial Institute, part of a larger effort by the Presbyterian Church to reach out to immigrants from Russia. [40] While Šmits is remembered for editing Kanādietis, he also most likely was the author of an obscure pamphlet, Russians in Europe and in Canada, published by the Board of Home Missions and Social Service of the Presbyterian Church. [41] The brochure identifies the author only as “A Lettish Canadian”, but the content suggests it was penned by someone with knowledge and experience similar to that of Šmits—if not by the man himself. [42]

Kanādietis, as far as is known, was the only publication produced by Latvian immigrants in Canada prior to the Second World War, although they also were readers of a number of newspapers and periodicals published in the United States and the homeland. [43] A Baptist newsletter, Strautiņš Tuksnesī (A Brook in the Wilderness), appeared in Edmonton, Alberta, in 1942 and continued publication until at least 1944 or 1945. [44] Many more publications appeared with the arrival of the post-war Displaced Persons generation of Latvians, most of them in eastern Canada.

Kanādietis belonged to a tier of smaller Latvian publications in North America. The most widely distributed publications, all based in Boston, were the Christian-nationalist Amerikas Vēstnesis (1896-1920), closely aligned with the Lutheran German Missouri Synod; Strādnieks (1906–1918), the mouthpiece of the Latvian Association of the Socialist Party of America; and Proletāriets (The Proletarian, 1902-1917), affiliated with the Latvian Federation of the Socialist Labor Party. [45] As a local newspaper primarily serving the interests of the Winnipeg Lettish Friendly Association, Kanādietis might be viewed as a parochial publication, much like the various periodicals Latvians produced in places such as New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago. [46] However, its readership—and perhaps its influence—spread beyond Winnipeg and the prairie provinces.

Physically, Kanādietis was a small newspaper, normally running eight pages. Pages were numbered continuously from issue 1 through the final issue in July 1914, a total of 188 pages. The first page of each issue usually featured a poem and an essay or a story. The essay or story usually was continued on page 2, although sometimes another essay or story might be featured. Pages 3 and 4 were reserved for continuations, from previous issues, of various other essays, stories, or informational articles on topics such as homesteading regulations or the status of workers in Canada. Page 5 might feature a short article on personal health or other topics. Pages 6 and 7 contained news sent in by “correspondents” in various Latvian colonies in Canada, the United States, and even such distant locations as Scotland, Brazil, and Siberia. These items ranged from short reports of organizational meetings (usually of the Winnipeg Lettish Friendly Association) to colourful vignettes of family and community life. Page 7 also might carry reports gleaned from newspapers in the Baltic provinces as well as from around the world. Page 8 was mostly reserved for the few advertisements Kanādietis managed to get, as well as for answers to readers’ queries and the occasional editor’s note. Dozens of writers submitted their work to the newspaper, but their identities often were shrouded by noms-de-plume. Among the most published were Teodors Rolands, Augusts Skupiņš, and Kārlis Žagata (Charles Schagat). Rolands was a bricklayer who lived in Lac du Bonnet; Žagata, a merchant who lived in Edmonton; and Skupiņš lived in New York City, according to immigration and census records. Šmits also used the newspaper to publish part of his English-language primer for Latvian speakers, a project he had started while living in England and would only be able to finish when he returned to Latvia. A year’s subscription to the newspaper cost two dollars in Canada and the United States, but only two rubles or one dollar in Russia and elsewhere. Depending on demand, the intention of the publishers was to eventually grow Kanādietis into a weekly newspaper. [47] The circulation of Kanādietis has not been determined, although one critic of the newspaper claimed the newspaper distributed only about 150 copies. [48] By comparison, the publishers of Strādnieks in mid-1915 were striving to increase the newspaper’s subscribers to 2,000 and to move to thrice-weekly publication. [49]

Although in later months its relationship with Strādnieks would sour when the Boston newspaper ran a scathing critique of Kanādietis, the first issue was printed in the former’s shop in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, because the Gothic type Kanādietis had ordered had not arrived on time. [50] Likewise, the second issue was delayed and was combined with the third because the type still was delayed. Further, editor Šmits explained, subscriptions were slow in coming. As a result, the paper could not afford to hire professional typesetters but instead had to rely on local Latvian women who had never even seen a printing press operate. [51] Lack of subscription revenue continued to be noted by Kanādietis throughout 1913, although only in the end did the editor put the blame on Canada’s economic downturn as one possible reason for the newspaper’s financial misfortunes. [52] Advertising revenue also must not have been great. No rate data were published in the paper, so it is not possible to determine potential revenue, but few issues carried much advertising.

As editor, Šmits combined Christian religious belief with a sensitivity for working-class struggle, although the pages of Kanādietis did not suggest dogmatism on his part nor even hint at the Presbyterian faith he had adopted. In the first issue, the editor asked readers to view the publication not just as a newspaper, but as “a telephone station for the soul” from which they could share experiences and help each other. He wrote:

The goal of Kanādietis is nothing more than to be the resource through which the disparate, scattered scions of our people can be brought together and not be allowed to wither away. Contact with people related to us makes us strong and unites us in cooperation and struggle against the oppressive conditions of life and prevents us from sinking into hopeless, cowardly despondency. [53]

Whether the newspaper in its short existence accomplished its goals is not for this researcher to judge, but the publication certainly attempted to describe and ameliorate those “oppressive conditions of life”. Through news reports and dispatches from correspondents in various Latvian immigrant colonies, through short stories and poetry, and through essays, the editor of Kanādietis embraced a discourse that was governed by three overriding themes. One, which I have termed paradise lost, lamented the loss of homeland (whether voluntarily or not), the inability to return there, and the difficulty of finding happiness in the immigrants’ new home. Another, reconciliation, sought through cultural criticism to deal with the rift between socialist and secular Latvians on the one hand, and nationalist and religious Latvians on the other. Finally, the theme of search for spiritual community spoke to the inability—at least in the eyes of editor Šmits—of either radical socialism or blind religious faith to touch the souls of the majority of Latvian immigrants who appeared trapped between these two extremes. Early issues of Kanādietis eagerly spoke of the potential of Canada as a destination for new Latvian immigrants, but seen in the context of the stated goals of the Winnipeg Lettish Friendly Association, I suggest that these articles were not evidence of a separate theme, but rather a subset of the search for community: The more Latvians arriving in Canada, the greater the potential that the spiritual community could be realized.

Several essays, poems, and short stories addressed the theme of paradise lost. In one example, the rough outlines of immigrant Latvian discourse—as well as an indication of the polarity of ideologies—were revealed in the first and second issues of Kanādietis in a short story by a writer from Alberta known only as Pastarītis (The Youngest Child). “Dzimtas vieta” [54] (“The Home Place”) appeared to take place in rural, western Canada and depicted the chance meeting of Pēteris Krūze, a young, idealistic social democrat, and Jānis and Maija Bērziņš, Latvian immigrants who had come years earlier to start a new life as farmers. Jānis Bērziņš, in town to pick up supplies, spies Krūze in a railroad depot carrying a copy of Strādnieks. Bērziņš invites him home to meet his wife and to spend the evening. In the course of dinner conversation, the ideological tension between Krūze and the Bērziņš couple is developed. Krūze accepts the existence of only two classes: the capitalists and the workers. The Bērziņš couple sees the world in more nuanced terms. To them everyone, in essence, must struggle to find happiness. Although the couple appears religious, their faith is more philosophical than sectarian. In their garden are the graves of their two young children. Jānis Bērziņš relates to Krūze, before the latter’s departure the following day, that he and his wife can never return to their homeland, because their “home” is this plot of land in which they have buried their children. Their struggle is not with those who control the means of production, but with life itself.

Other examples of the theme of paradise lost included a love story about a young Latvian immigrant pining for his betrothed back in the homeland; [55] a poem expressing sorrow for the homeland never to be seen again; [56] and another love story with an old oak tree symbolizing the roots of the homeland to which the immigrant cannot return to reclaim his love. [57]

Although fictional, the Bērziņš couple and Krūze might be seen as archetypes of the Latvian immigrant, a theme developed by Šmits in a two-part essay examining social relations and how they change for Latvian immigrants. [58] Šmits suggested that four types of Latvian immigrants could be discerned: 1) those who did not have deep roots in the homeland, seemed ashamed of their ethnicity, and who dressed and acted like “Americans”; 2) those without deep roots in the homeland but who could not easily acculturate, “like ripe apples…within which the worm has begun its terrible work of extermination”; 3) those with deep roots in the homeland, who dream of one day returning, no matter how well-off they might become, and 4) those who came seeking fortune and live by the motto, “Where I prosper, there is my homeland.” In a sombre tone, the editor wrote his analysis of immigrant life, focussing on the pain felt by the third type of Latvian immigrant:

The years pass. The children of immigrants become men. The men begin to grow old. Life moves forward, but Death does its work as well. Death’s scythe has already plowed down a few good immigrants. For the living, their former dear, strong ties to the homeland are severed one by one. Little by little their hopes of once again finding the paradise of youth disappear, vanish. It is not possible to live if life does not have value and if one does not know for what and for whom one should live. [59]

Certainly the Bērziņš couple would fit this characterization, and so might the social-democrat Krūze, for whom it might not yet be too late to find paradise. While lamenting the fate of this group of immigrants, Šmits urged his readers to come together to help one another. He continued:

We can forget and care not for those people whom we left behind in the homeland, but we should never forget our brothers in fate who did not have the fortune to find for their new lives in a foreign place such favorable conditions as we. Let he who is on sound footing therefore not forget to lend a hand to those who have not yet found and cannot find for their lives such a firm support. Under current conditions the emigrants’ contact with and assistance to one another is the surest path from such a hopeless life. [60]

To heal the pain of paradise lost, a number of articles in Kanādietis urged reconciliation of the various elements of Latvian society in North America. Among Šmits’ own writings, perhaps the most important was the series “Amerikas latviešu garīgais stāvoklis” (“The Spiritual Condition of America’s Latvians”), which ran from 30 March until 15 October 1913. The series, which also focussed on the search for spiritual community, was an exercise in cultural criticism aimed at pointing out the faults of both extremes of the American Latvian socio-political spectrum. Much attention in the series focussed on Amerikas Vēstnesis and Strādnieks as symbols and as messengers of the sectarianism Šmits suggested was dividing Latvian immigrants rather than uniting and strengthening them. Šmits wrote, “We will endeavor here to find those foundations of spiritual life on which America and in particular Latvians seek balance in their lives and on which they construct their lives.” [61] Latvian immigrants, he added, were not enamoured of the elitism of Strādnieks, whose editors Šmits advised should keep in mind the oft-mentioned idealistic goals of socialism and forget the paper’s provincialism, a reference no doubt both to Strādnieks’ editorial stance as a party newspaper and its geographical location in Boston. Amerikas Vēstnesis, meanwhile, was criticized for its narrow and intolerant attitude toward any religion other than its own brand of Lutheranism, a situation that Šmits argued retarded the spiritual development of readers.

The themes developed in Kanādietis revealed how Šmits and the other writers navigated the early stages of ritual transformation. The loss of paradise—the yearning for the homeland—described the rite of separation, while the attempt to reconcile different ideologies and the desire for a new spiritual community suggested the rite of transition, or the liminal phase. Latvian immigrants in western Canada, some of whom had been there for two decades and others for just a few years, were engaged in a familiar process to try to make sense of their lives in new surroundings. However, the newspaper’s contribution to that process was hindered and ultimately thwarted by the opposition Šmits and the Winnipeg Lettish Friendly Association faced from the radical socialists in Winnipeg and Lac du Bonnet, who actively worked to disrupt the efforts of the association, even suggesting a boycott of the newspaper.

That the socialists had influence in Latvian communities in Canada is undeniable, as they established a number of clubs. In 1914, the Winnipeg chapter of the Latvian Association of the Socialist Party of America had 18 members, while the newly established Lac du Bonnet chapter had 17. Across western Canada, chapters were also operating around this time in Medicine Hat, Alberta; Port Arthur, Ontario; and Vancouver, British Columbia. Chapters had formed in 1909 in Fernie, British Columbia, and Montréal, Québec, but it is not known if they were still active in 1914. A Latvian socialist group also existed in Toronto.

Of course, the socialists read Kanādietis, but they were not about to support it by taking out subscriptions, and the vitriol against the newspaper continued for years. When Šmits sought to renew his “swindle sheet” in 1914, it was the socialists of Lac du Bonnet whose attack “completely killed it”, recalled a former member of the local club writing a decade later. [62]

If reconciliation was indeed the goal, an attack against Kanādietis by the socialist Strādnieks in the spring of 1913 must have stung Šmits and others associated with the newspaper. In a review, Strādnieks chastised Kanādietis for its seemingly lukewarm political stance, saying the Canadian paper glossed over the Russian czar’s acts of terror as if they were merely examples of government discipline, hoped in vain for amnesty for Latvian revolutionaries, and carried little political news. [63] The essays and editorials in Kanādietis “are without end, like Canada’s forests,” Strādnieks added. “They chatter about how new immigrants grow old, and Death’s scythe plows down the aged. Who would have thought it!” Worse yet, Strādnieks continued, were the literary offerings in Kanādietis:

The stories are noteworthy for their sentimentality. One almost has to cry while reading them: there are the crosses of children’s graves at the end of a farmer’s field, the emigrant fiancés longing for their brides and shocking scenes when these fiancés trot to the railroad station…to send their fiancée a ticket. All this leaves a “powerful” impression on the experienced reader.

The boosterism of Kanādietis toward life in Canada also was questioned. Accusing the paper of petty bourgeois behaviour, Strādnieks particularly questioned the accuracy of wage rates for seamstresses quoted in Kanādietis, figures that suggested these Canadian workers made more money than their American counterparts. This was the only point on which Kanādietis formally responded, citing Canadian government figures that backed up its contention. [64] Not surprisingly, after the Strādnieks critique, advertisements for the socialist newspaper no longer appeared in Kanādietis.

A second attack came in September, penned by someone familiar with the socialist local in Winnipeg and with Šmits. The writer accused Šmits of being a hypocrite for seemingly supporting progressive ideals while at the same time criticizing Strādnieks for its editorial stance. Furthermore, Kanādietis used poor grammar and jargon. The newspaper’s core group of writers were “unrecognized geniuses” who had found a venue for their work after they had “unsuccessfully bombarded the wastebaskets of newspapers and calendars in the Baltics.” [65]

Although some potential subscribers of Kanādietis may have rejected the newspaper outright because it was not a socialist publication, one observer—a self-described supporter of socialism—came to the newspaper’s defence in the 15 July 1913 issue. “Having read a number of Kanādietis issues, I have come to the conclusion that it is a completely progressive and nonpartisan newspaper,” A. Balods wrote. He suggested that the Winnipeg socialist club itself had become too partisan, accepting as true socialists only those who belonged to the party, which of course needed only one party organ—Strādnieks. While Strādnieks certainly had an important role among Latvians throughout North America, Balods wrote, Kanādietis also could play a part. Rather than attack it, readers should support it by submitting worthwhile and progressive articles. Only if the newspaper rejected those articles, Balods concluded, should readers boycott Kanādietis. [66]

While Šmits’ dream of unifying the Latvian community through the pages of Kanādietis was beginning to fade, his wider religious work among Russian immigrants also experienced challenges. In May 1913 Šmits began working for the Robertson Memorial Institute, a mission established by the Presbyterian church to reach out to immigrants in Winnipeg. He ran the institute’s Russian reading room and taught English, but initially encountered opposition from the immigrant community and, for a while in 1914, saw his classes boycotted. As in his critique of duelling ideologies in the Latvian community, Šmits pointed to the rift among the Russians. “The Russian papers in America are the organs either of the Orthodox Church or of the extreme Socialistic parties,” he wrote, and acknowledged the early problems he faced at the institute. “The work has created alarm and the people have been forbidden to enter the reading-room.” [67] Peter George Bush, in his study of the Presbyterians’ mission work in Canada, noted that during the time Šmits worked in the institute, only four Russians became converts and joined the Robertson Memorial Presbyterian Church, although “his ability to act as translator, employment agent, and cultural interpreter made him a valued member of the Russian community.” [68]

Discord between Šmits and the socialists did not end with Kanādietis. A month after the newspaper’s final issue appeared in July 1914, a correspondent for Strādnieks analyzed the structure of the Lac du Bonnet community, which included two lending libraries, a socialist club, and a cultural association named Druva. The writer particularly criticized Druva for its failure to address issues of concern to the working class, unlike the local socialist club. The writer observed that Druva was organized similarly to the Winnipeg Lettish Friendly Association and was influenced by Šmits and his ill-fated Kanādietis. [69]

In June 1915, Šmits—in his capacity as manager of the Presbyterian Russian Reading Room in Winnipeg—wrote a letter to the editor of the Manitoba Free Press. The letter addressed “the unintended wrongs practiced in Winnipeg by the public authorities which inflict much suffering on the poor Russian working men here, in the country of their allies of whom they are so proud.” At issue were job assignments on the railroad given out in employment offices. Šmits claimed that because some of those working in the offices were Austrians or Jews, they discriminated against Russians (the Austrians because the Austro-Hungarian Empire was at war with the Russian Empire, the Jews because of how they were treated in the Russian Empire). The letter drew a rebuke from R. Stallit, who questioned Šmits’ background and his apparent anti-semitism. Referring to Šmits as “Herr Schmidt”—intimating that he was German—Stallit asked “[t]o what race does he belong” and “[s]ince when does he defend the Russian bureaucracy?” Stallit, who suggested he was personally familiar with Šmits, wrote that “a good deal, if not all the sins of the Russian Government have been due to Teutonic influence, and to the machinations of Herr Schmidt.” Šmits responded with a brief history lesson about Latvians’ struggle under the Germans, adding that Stallit had misread his intentions. “I do not ask for special favors for the Russians, nor do I wish to see either the Jews or Austrians treated worse than at the present time,” Šmits wrote. “My only desire was to avert some abuses of the Russians which are caused by the partiality of the officials dealing with them.” [70]

If Šmits earlier had been open to reconciliation with the socialists, by 1920 it appeared he had turned his back on them—as they had on him. Having repatriated to his homeland, Šmits wrote a commentary for the newspaper Latvijas Sargs in which he attacked Latvian socialists in America, observing that “they have always been the most acrimonious opponents to Latvian sovereignty,” desiring instead that Latvia become part of the Soviet Union. On a personal note, Šmits wrote that when he was preparing to return to Latvia, he had reached out to former socialist friends of his, offering that they come with him or that he at least could bring letters to the homeland. Their responses to his offer, Šmits wrote, were only full of condemnation for his decision. [71]

The aftermath of the October 1917 revolution in Russia was seen by some Latvian emigrants in North America as an opportune time to return to the homeland. Some wanted to help build the new Soviet state; others saw the potential of an independent Latvian republic. Šmits and a number of other Latvians sailed to Vladivostok in hope of making their way home but, due to fighting across Russia, found themselves in limbo. [72] Šmits worked in several teaching jobs, including at the Far Eastern Institute. He stayed in Vladivostok until April 1919, perhaps timing his return with that of the withdrawal from Russia of the Canadian Expeditionary Force that was part of an allied effort to thwart the Bolsheviks. [73] He reunited with his wife and son waiting in Manitoba—returning to a radicalized Winnipeg that was primed for the General Strike about to erupt in May. Šmits briefly helped raise money for his homeland, serving as corresponding secretary of the Lettish Relief Committee in Winnipeg. He wrote an article for the Winnipeg Free Press, describing the Latvian people and their aspirations, as well as appealing for donations in cash and goods from Canadians to aid the newly independent country. [74] But Šmits had had enough of what he perceived were the radical political leanings of his countrymen in North America, observing in an October letter to the Latvian Information Bureau in London, England, that “almost all are ill with the fever of bolshevism.” Unable to find suitable employment and sensing that by staying in Winnipeg he could not be of further assistance to the homeland, Šmits determined again to return to Latvia, this time via England. [75]

In November 1919, the family finally repatriated to Latvia, where Šmits took a teaching position in the port city of Liepāja. In 1922, he was made director of the new Rīga English Institute, part of the Ministry of Education. [76] Šmits continued to actively teach and publish as well. He wrote books about the English language, took part in lessons broadcast over radio, and led tours to England for students. [77] However, the Soviet takeover of Latvia in June 1940 led to changes in the institute he had directed for almost two decades. By order of the people’s commissar of education, the Rīga English Institute in October 1940 became the State Language Institute of Rīga (Rīgas valsts valodas institūts), also offering courses in French and Russian. [78] Although Šmits continued in his role as director, it soon became clear that he would not last. Just days after the education commissar’s order was published, a brief story appeared in the youth communist newspaper Jaunais Komunārs noting the “unacceptable events” that had occurred in the opening days of the institute’s new academic year. The director (in other words, Šmits) had “openly announced that he does not feel suited to the new conditions and is incapable of leading the institute in the spirit of the new times.” [79] Further, he had failed to arrange for a representative of the Latvian Communist Party to speak to students. The “most responsible” students, the article concluded, were ready for radical change in the institute.

As German troops advanced into occupied Latvia, the Soviets in June 1941 deported an estimated 15,000 persons to Siberia, including Šmits and his wife, who were separated in Rīga and shipped to different locations. Šmits was sent first to Solikamsk, but died in 1942 on the way to Krasnogorsk. Anna survived. She was sent first to Narimskij kraj, but later moved to Prokopevka and then to Novokuznetsk. In 1960, she was allowed to emigrate to the United States, where she joined her son Rudolf’s family in Chevy Chase, Maryland. [80] Rudolf, who had previously worked in the American Legation in Rīga, had moved to the United States before the war and from 1936-1940 served as a secretary in the Latvian Legation in Washington, D.C. He then joined the Library of Congress and worked on a number of projects, including the Cyrillic Bibliographic Project. [81]

It is perhaps a fitting irony—or a self-prophetic last gesture of desperation—that Kanādietis disappeared at the end of 1913. In the final issues of the year the newspaper attempted to draw some closure to the problems that Šmits and his supporters had been writing about all year. Friction between the Winnipeg Lettish Friendly Association and the socialist local, hinted at or mentioned in passing throughout the year, was addressed directly by Šmits in the 30 November issue. [82] Concurrently, however, the paper suggested hope for the future unity of Latvian immigrants in Canada, at least in Manitoba. The Winnipeg Lettish Friendly Association, apparently somewhat unilaterally, decided to create a co-operative association between Winnipeg’s urban Latvians and the rural Latvian colonists of Lac du Bonnet. Kanādietis naturally gave much coverage to the progress of incorporation, but after discussions in late 1913 the plan must have foundered, perhaps because the Lac du Bonnet Latvians were skeptical. No record exists of a co-operative association actually having operated among the Latvian immigrants.

It is doubly ironic that Kanādietis, which had defended itself against Strādnieks over the issue of Canada’s favourable economy, in the end admitted that tough times in Winnipeg and elsewhere—along with lack of a strong subscriber base—were the paper’s undoing. When the two women who worked as the publication’s typesetters announced that they could no longer continue in Winnipeg, Kanādietis was forced to suspend operations.

Six years after the newspaper folded, Šmits remained convinced that Latvians in North America needed an alternative voice. In a letter to Andrejs Saviņš, who in 1919 established the organization Lettish Bureau “Latvia” in New York and whose work also was criticized by the leading newspapers on the right and the left, Šmits complained that neither Amerikas Vēstnesis nor Strādnieks provided readers with what they needed: a venue where they could freely express their thoughts and gain objective news. [83] However, the former newspaper editor, who had sought to lead readers in the transformation of Latvian immigrant life but had failed in the endeavour, could only offer his colleague best wishes.

1. Kanadeetis was the spelling of the newspaper’s name in the old, Gothic orthography used by many Latvian publications well into the 1920s. In the new, Latin orthography, the spelling would be Kanādietis. Throughout this article, I have adopted the Latin orthography for spelling of Latvian titles and names.

2. For a brief overview of the Latvian immigrant press of this period— and one of a very few scholarly treatments of the subject—see Edgar Anderson and M. G. Slavenas, “The Latvian and Lithuanian Press,” in Sally M. Miller, ed., The Ethnic Press in the United States: A Historical Analysis and Handbook, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1987, pages 229–245.

3. Technically, only 22 issues appeared, because issue 2/3, published 28 February 1913, was a double issue.

4. Stephen Harold Riggins, “The Media Imperative: Ethnic Minority Survival in the Age of Mass Communication,” in Riggins, ed., Ethnic Minority Media: An International Perspective (Newbury Park, California: SAGE Publications Inc., 1992), page 4.

5. James W. Carey, Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society, Boston: Unwin Hyman Inc., 1988, page 34.

6. Ibid.

7. Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1960.

8. Victor Turner, Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1974; Turner, From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play, New York: PAJ, 1982.

9. Turner, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969, pages 94–95. For a further elaboration, see Ronald L. Grimes, Rite Out of Place: Ritual, Media, and the Arts, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

10. For example, papers of the socialist Boston Latvian Workingmen’s Society and the communist Latvian Workers Union of America (which include minutes of the Vancouver Latvian Workers Society) are held by the Latvian State Archives in Rīga, while the papers of the Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Church of St. John in Philadelphia are held by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. This is not to say that other records of early Latvian immigrants do not exist. The author has been directly involved in acquisition or is aware of the existence of at least two Midwestern US collections pertaining to the pre-Second World War period. Meanwhile, the minutes of the Latvian socialist club of Lac du Bonnet, Manitoba, were discovered recently and are now in the hands of an independent scholar.

11. In Latvian press reports, settlements of Latvian immigrants were called kolonijas, or colonies. The word does not appear to have carried with it the deliberateness usually associated with colonization. In North America, only the farming settlement in Lincoln County, Wisconsin, could be considered a “true” colony in that deliberate efforts were made to create a concentrated Latvian community. In Canada, Latvian settlements such as the one at Lac du Bonnet, Manitoba, developed somewhat organically.

12. General coverage of Latvian immigration is found in Vilberts Krasnais, Latviešu kolōnijas (1938; rpt. Melbourne: Kārļa Zariņa fonds, 1980); Osvalds Akmentiņš, Latvieši Amerikā, 1888–1948: Fakti un apceres, Lincoln, Nebraska: Vaidava, 1958; Maruta Kārklis, Līga Streips, and Laimonis Streips, comp. and eds. The Latvians in America, 1640–1973: A Chronology and Fact Book, Dobbs Ferry, New York: Oceana Publications Inc., 1974; Akmentiņš, comp. Latvians in Bicentennial America, Waverly, Iowa: Latvju Grāmata, 1976; Līga Dūma and Dzidra Paeglīte. Revolucionārie latviešu emigranti ārzemēs, 1897–1919, Rīga: Liesma, 1976; Akmentiņš, Vēstules no Maskavas: Amerikas latviešu repatriantu likteņi Padomju Krievijā, 1917–1940, Three Rivers, Michigan: Gauja, 1987; and Akmentiņš, comp., Raksti par latviešu presi, Dorchester, Massachusetts: The author, 1990. For Canada, see Pauls Kundziņš, Latviešu immigrācijas sākumi Albertas provincē Kanadā un Kārļa Pļaviņa sēta, Three Rivers, Michigan: Gauja, 1979; Jane McCracken, The Overlord of the Little Prairie: Report on Charles Plavin and His Homestead, Edmonton: Alberta Culture, 1979; Ausma Janitens-Birzgalis, Latvians in Alberta: A Study, Calgary: The University of Alberta, 1980; and Akmentiņš, Latvieši Albertā/Latvians in the Province of Alberta, Canada, Dorchester, Massachusetts: The author, 1985.

13. Arveds Švābe, “History of Latvia,” in Edgars Andersons, ed., Cross Road Country—Latvia, Waverly, Iowa: Latvju Grāmata, 1953, pages 305–306.

14. By 1914, the population grew to more than 2.5 million, but the ravages of the First World War, which included migration of tens of thousands of refugees to the heart of the Russian Empire, reduced the population to 1.59 million by 1920. Returning refugees boosted the population to 1.85 million by 1922. “Iedzīvotāju skaita pieaugšana kopš 1800. g.,” Latvijas statistiskā gada grāmata, 1921 (Rīga: Valsts statistiskā pārvalde, 1922), p. 2.

15. Krasnais, Latviesu kolōnijas; Akmentiņš, Amerikas latvieši; Dūma and Paeglīte, Revolucionārie latviešu emigranti ārzemēs; Kārklis et al., The Latvians in America.

16. Kārklis et al., The Latvians in America, pages 5–6.

17. Francis J. Brown and Joseph Slabey Roucek, eds., Our Racial and National Minorities: Their History, Contributions, and Present Problems, New York: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1937, pages 262–270.

18. Ralph Connor, The Foreigner: A Tale of Saskatchewan, New York: Grosset & Dunlap, Publishers, 1909. Ralph Connor was the pen name of Presbyterian minister the Rev. Charles William Gordon (1860–1937). Although the novel is about a Galician settlement in Saskatchewan, the staging point for the characters’ migration to the province is Winnipeg.

19. Jean R. Burnet and Howard Palmer, “Coming Canadians”: An Introduction to a History of Canada’s Peoples, Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1988, page 30. Among marketing schemes used by the Canadian government was the organizing of junkets by small-town and rural US newspaper editors, according to Robert England, The Colonization of Western Canada: A Study of Contemporary Land Settlement, 1896–1934, London: P. S. King & Son, 1936, page 68.

20. W. L. Morton, Manitoba: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1957), pp. 329-331. See also Alan F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874-1914 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1975); Artibise, Winnipeg: An Illustrated History (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 1977); and Jim Blanchard, Winnipeg 1912 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2005).

21. "Jelgavas notikumi," Latviešu Avīzes, 3 February 1888, p. 4.

22. J. Fischers, "Vēstule iz Amerikas," Latviešu Avīzes, 1 June 1888, p. 1.

23. Sm., "Par latviešu kolonistu dzīvi Ziemeļamerikas Savienotās Valstīs," Latviešu Avīzes, 28 August 1912, p. 1. See also a warning about being taken in by immigration agents’ advertisements, K. Žagata, “No Kanādas,” Dzimtenes Vēstnesis, 20 June 1909, p. 6.

24. For background on immigration to Canada, see, for example, Burnet and Palmer, “Coming Canadians”; England, The Colonization of Western Canada, and W. G. Smith, A Study in Canadian Immigration, Toronto: The Ryerson Press, 1920.

25. Anna V. (Gulbis) Turton, The House Beside the Rock Hill, Swan River, Manitoba: self-published, 2010. The book is the story of the author’s parents, who were among those Latvians who lived in the Bird Island settlement.

26. Attempts to identify ethnic Latvians in census records of the period can be frustrating, and thus the number of individuals could indeed be much more than 500. An ethnic Latvian born in the part of the Russian Empire that become modern Latvia might identify himself or herself as Lettish or Russian—or even Canadian. In Alberta, the Medicine Hat News in 1912 reported that the “100 or so” Latvians in the city were angry with the chief of police, who had categorized them in the 1911 census as German rather than Russian. “These people say they are more Russian than they are German, but prefer being considered Canadians, as the majority of them are naturalized Canadians,” the newspaper reported. “Lettish People Very Angry,” Medicine Hat News, 22 October 1912, p. 8.

27. Celmlauzējs, “Kā latvieši dzīvo svešās zemēs,” Kanādietis, 30 January 1913, pp. 7-8.

28. Dominion Bureau of Statistics, Origin, Birthplace, Nationality and Language of the Canadian People: A Census Study Based on the Census of 1921 and Supplementary Data, Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics, 1929, page 51.

29. Bureau of Statistics, Census of Prairie Provinces, 1926: Population and Agriculture, Ottawa: F. A. Acland, 1931, pages xxxviii, 82, 84, 86, 89, 91.

30. Dūma and Paeglīte, Revolucionārie latviešu emigranti ārzemēs, p. 295.

31. Jēkabs Zībergs, Svētdienas skolas lasamā grāmata (Cambridge, Massachusetts: J. Sieberg, 1920), pp. 226-227, 230-231. The congregations were formed during tours by the Rev. Hans Rebane of western North American Latvian colonies in 1897 and 1900. Akmentiņš, Latvieši Albertā/Latvians in Alberta, p. 32. The page is a reproduction of an undated article, “Eksperiments ar 4000 latviešiem” (“An Experiment with 4,000 Latvians”) published during 1969 in the Toronto-based exile Latvian newspaper, Latvija Amerikā.

32. The Rev. Michael Lodsin (1862-1918), a Latvian Baptist minister working among immigrants at Ellis Island in New York, in 1912 described visiting his brother in rural Manitoba, where he led several religious meetings among residents: “At some of them they had no Christian worker, pastor or priest for ten or twelve years, and some are very hungry for God’s word, while others have been hardened; these meetings were usually held by night because the people have too much to do by day.” “Colporter Missionary Lodsin’s Trip to Western Canada,” Missions: A Baptist Monthly Magazine, 3:6 (June 1912), p. 493.

33. In Latvian, the association was known as Vinipegas Latviešu sadraudzīgā biedrība. J. Šmits, “Pirmā latviešu biedrība Kanādā,” Tēvija, 30 August 1912, p. 1. See also "Ziņojumi," Kanādietis, 15 June 1913, p. 81.

34. Šmits the Kanādietis editor has been confused with Jānis J. Šmits (John J. Schmidt, also known as Šmitu Jānis), a minor Latvian writer known for his literary sketches. The latter immigrated to the United States in 1904—when the former was still teaching in Latvia—and eventually worked for the Chicago Public Library, where he prepared guides to the Latvian and Russian collections. For details, see Teodors Zeiferts, Latviešu rakstniecības vēsture, 3. daļa, III izdevums (Vaidava, 1959), p. 334. In his compilation about Latvian writers, Alberts Prande, Latvju rakstniecība portrejās (Rīga: LETA, 1926), p. 264, erroneously conflated the two Šmitses into one person. Neither must the editor of Kanādietis be confused with another Jānis Šmits (John Schmidt), who was editor of the leftist literary journal Jaunais Prometejs (The New Prometheus), a short-lived bimonthly that appeared during 1927 in Boston. His writings had been published earlier in Latvian anarchist periodicals under the pseudonym Rucelis.

35. K. Beierbahs, Aizputes karš: Revolūcjas masustāsts 1905.g. (Rīga: self-published, 1933).

36. Šmits, Jānis, 1876-1941. “Autobiogrāfija, atmiņas par dalību 1905. gada revolūcijā, avīžrakstu rokraksti. 1905-1930.” Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection, National Library of Latvia, Rīga.

37. In March 1906, the official Russian-language newspaper for Kurzeme published a supplement listing the names of 79 persons sought by authorities. No. 1 on the list was the teacher from Tāši-Padure – Šmits. Курляндские Губернские Ведемости, 19 March 1906. See also “No Tāšu-Padures,” Mūsu Laiki, 13 March 1906, p. 2, and “Aizbēguši un tiek meklēti,” Mūsu Laiki, 31 August 1906, p. 2.

38. Šmits was referred to as a Baptist in R. Endrups and A. Feldmanis, comp., Revolucionāro cīņās kritušo piemiņas grāmata, 2. sejums, 1907-1917 (Moscow: Prometejs, 1936), p. 395.

39. Charlotte Alston, “Britain and the Tolstoyan Movement,” in Rebecca Beasley and Philip Ross Bullock, eds., Russia in Britain, 1880–1940: From Melodrama to Modernism, Oxford University Press, 2013, page 64; Elina Thorsteinson, “The Doukhobors in Canada,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 4:1 (June 1917), pages 3–48.

40. Vadim Kukushkin, From Peasants to Labourers: Ukrainian and Belarusan Immigration from the Russian Empire to Canada, Montréal: McGillQueen’s University Press, 2007, pages 316–317. Echoing the tension in the Latvian community, Kukushkin noted how the reading room’s free access to newspapers and journals attracted Russian workers, which “became a source of permanent concern for the nearby Russian Progressive Club.”

41. A Lettish Canadian, Russians in Europe and in Canada, The Board of Home Missions and Social Service, no date.

42. Akmentiņš, Latvieši Albertā/Latvians in Alberta, p. 33. Edgars Andersons, ed. Latvju Enciklopēdija 1962-1982 (Rockville, Maryland: American Latvian Association, 1990), p. 569. Passport nr. 182197 for Jānis (Andreja d.) Šmits and page 84 of the registry for the apartment building at 11 Kuģu Street (Kuģu n. 11) in Rīga, both held by the Latvian State History Archives, confirm some aspects of the Šmits biography.

43. It is, however, interesting to note that a wartime ban on publishing newspapers and periodicals in “enemy languages,” issued as an order-in-council in September 1918, just a month-and-a-half before the armistice, included the Livonian (another term for Latvian) language. Smith, A Study in Canadian Immigration, pages 147–148.

44. Akmentiņš, Latvieši Albertā/Latvians in Alberta, pp. 105-106.

45. Circulation figures for these publications are scarce. Strādnieks, the largest newspaper, at this time was published semi-weekly.

46. See Anderson and Slavenas, “The Latvian and Lithuanian Press, ”and “Vēl daži vārdi par laikrakstiem,” Amerikas Latvietis, 9 June 1966, p. 3.

47. “Jauns latviešu laikraksts Amerikā,” Liepājas Atbalss, 29 December 1912, page 2.

48. Pilsētnieks, “Iz Vinipegas,” Strādnieks, 23 September 1913, p. 2.

49. Organizācijas komiteja, “2000 abonenti līdz 1. jūnijam,” Strādnieks, 30 April 1915, p. 1.

50. “Redakcijas gala vārds pie ‘Kanādieša’ pirmā numura,” Kanādietis, 30 January 1913, p. 10.

51. “Redakcijas atbildes un paskaidrojumi,” Kanādietis, 28 February 1913, page 28.

52. Kanādietis, 15 December 1913, page 180.

53. “‘Kanādieša’ sveiciens lasītajiem,” Kanādietis, 30 January 1913, p. 1.

54. Pastarītis, “Dzimtas vieta,” Kanādieties, 30 January 1913, pp. 2-4; 28 February 1913, pp. 15-19.

55. Juris Dzirkstele, “Kura tā īstā” (“Where Is My True Love?”), Kanādietis, 15 March 1913, pp. 30-31. The story continued in subsequent issues.

56. [Ringantis?], “Ilgas,” Kanādietis, 30 March 1913, pages 37–38.

57. Teodors Rolands, “Senie zvani,” Kanādietis, 30 April 1913, page 54. The story continued in subsequent issues.

58. “Latviešu emigrantu dzīve un izredzes,” Kanādietis, 28 February 1913, pages 13–14; 15 March 1913, pages 29–30.

59. “Latviešu emigrantu dzīve un izredzes,” Kanādietis, 28 February 1913, pages 13–14.

60. “Latviešu emigrantu dzīve un izredzes,” Kanādietis, 15 March 1913, p. 29.

61. “Amerikas latviešu garīgais stāvoklis,” Kanādietis, 30 March 1913, p. 37.

62. Čāgans, “Sarkanais karogs Kanādas mežos,” Strādnieku Rīts, 5 December 1925, p. 8.

63. “Laikrakstu apskats,” Strādnieks, 22 April 1913, p. 2. The author of the review, which was based on a reading of the first four issues of Kanādietis, is not known, although it likely was Editor Jānis Ozols (1878-1968). Known also by the noms-de-guerre Zars and Hartmanis, Ozols in Latvia had been a founder of the Latvian Social Democratic Labor Party and of the underground socialist newspaper Cīņa (The Struggle). He arrived in the United States in 1907 and served as editor of Strādnieks from 1909-1913.

64. Several months passed between the attack by Strādnieks and the official response, “Kanadieša atbilde Strādniekam,” Kanādietis, 30 October 1913, pp. 152-153. Kanādietis did, however, publish one poetic response soon after the attack, A. Skupiņš, “Pirmais sviediens no ‘St.,’” Kanādietis, 15 May 1913, pp. 63-64, and a brief comment from the editor, “Strādnieka uzbrukumi,” in the same issue, p. 66.

65. Pilsētnieks, “Iz Vinipegas,” Strādnieks, 23 September 1913, p. 2.

66. A. Balods, “Ko ļaudis klusībā spriež par ‘Kanādieti,’” Kanādietis, 15 July 1913, p. 97.

67. A Lettish Canadian, Russians in Europe and in Canada, The Board of Home Missions and Social Service, no date, pages 22–23.

68. Peter George Bush, Western Challenge: The Presbyterian Church in Canada’s Mission on the Prairies and North, 1885-1925 (Winnipeg: Watson & Dwyer, 2000), pp. 197-198. In the book, Šmits is referred to as John Andreyevitch Schmidt.

69. Ar., “Iz Lac du Bonnet latviešu kolonijas (Kanadā), ” Strādnieks, 14 August 1914, pp. 3-4. The author of the analysis most likely was Jānis Kļava, whose nom-de-guerre was Arķietis. Kļava ran a farm at Lac du Bonnet and was a founding member of the local Latvian socialist club. Before his arrival in Canada in 1912, Kļava had lived in Brazil, where he worked with the short-lived Latvian socialist newspaper Biedrotājs (The Organizer). When the radical socialist leader Fricis Roziņš returned to Latvia in 1917, he chose Kļava to take his place in the editor’s chair at Strādnieks. See Adolfs Uralietis, “Bijušie Ufas latvju kolonisti Brazīlijā,” Krievijas Cīņa, 25 May 1926, p. 2, and Čāgans, “J. Kļava (Arķietis),” Krievijas Cīņa, 6 January 1927, p. 3.

70. John Schmidt, “A Matter of Justice to the Slavic People,” Manitoba Free Press, 3 June 1915, pp. 9, 12; R. Stallit, “A Reply to John Schmidt,” Manitoba Free Press, 8 June 1915, p. 9; John Schmidt, “A Matter of Nationality,” Manitoba Free Press, 16 June 1915, p. 9.

71. J. Šmits, “Jautājums uz jautājumu,” Latvijas Sargs, 16 April 1920, p. 2. Šmits’ commentary was a response to an 11 April 1920, article in the newspaper Sociāldemokrāts that criticized the young Latvian Foreign Ministry about delays in processing citizenship papers for two prominent Latvian socialists living in the United States.

72. For an overview of the Latvian exile community in Vladivostok and the broader Russian Far East in the post-First World War period, see Aldis Purs, “Working Towards ‘An Unforeseen Miracle’ Redux: Latvian Refugees in Vladivostok, 1918–1920, and in Latvia, 1943–1944,” Contemporary European History, 16:4 (October 2007), pp. 479-494, as well as Aldis Bergmanis, “Latvieši Tālajos austrumos un atgriešanās dzimtenē 20. gadsimta 20.-30. gados,” Latvijas Vēstures Institūta Žurnāls, 2010:3(76), pp. 68-124.

73. Benjamin Isitt, From Victoria to Vladivostok: Canada’s Siberian Expedition, 1917–19, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010, examines the controversial and confused nature of Canada’s involvement in the Russian Far East following the Bolshevik revolution.

74. J. A. Smith, “Free at Last, But Starving,” Winnipeg Free Press, 13 September 1919, page 36. The article was reprinted in Alberta as “An Appeal for Help,” Medicine Hat Daily News, 25 November 1919, page 10.

75. Letter, J. A. Smith to Latvijas Informācijas Birojs, 27 October 1919, p. 157. lieta, 1. lp., fonds 2575, Latvijas diplomātiskās un konsulārās pārstāvniecības ārzemēs, Latvijas Valsts vēstures arhīvs, Rīga.

76. “Izglītibas ministrijas angļu valodas institūts, Rīgā,” Nedēļa, 20 March 1925, page 13. See also entries for Šmits in P. Kroders, ed., Latvijas Darbinieku galērija, 1918–1928, Rīga: Grāmatu Draugs, 1929, page 214, and P. Šmits, ed., Latvijas vadošie darbinieki, Rīga: Latvijas Kultūrvēsturiskā apgāde, 1935, pages 428–429.

77. Šmits and two faculty members of the Rīga English Institute in 1927 began language lesson broadcasts over state radio (“Angļu valoda pa radio,” Iekšlietu Ministrijas Vēstnesis, 25 October 1927, page 1). Beginning with the 21 September 1934 issue of the weekly magazine Atpūta, Šmits offered a “Basic English” course based on the work of C. K. Ogden. Also in 1934, Šmits published the book Angļu valoda Latvijā: iesācēju kurss. It was one of at least three works dealing with aspects of the English language in which Šmits was involved. In June 1938, Šmits accompanied 123 institute staff and students on a tour of Great Britain (“Latviešu skolotāji un studenti apmeklē Vindsoras pili un Itonas koledžu,” Rīts, 2 July 1938, page 1).

78. “Izglītības tautas komisāra pavēles,” Latvijas PSR Augstākās Padomes Prezidija Ziņotājs, 5 October 1940, page 1; “Pārkārtojumi mācības iestādēs,” Padomju Latvija, 5 October 1940, page 12.

79. “Nepieļaujami notikumi Angļu valodas institūtā,” Jaunais Komunārs, 14 October 1940, page 6.

80. Details about the Šmits family’s life during and after the Second World War were provided by a number of sources. Especially helpful were a two-part series based on a letter from Rudolfs Šmits to the historian Osvalds Akmentiņš, “Viens no daudziem,” Londonas Avāze, 11 October 1985, page 3, and 18 October 1985, page 3, and an interview with Anna Šmits after her arrival in the United States, P. L., “Divdesmit pieci rubļi pa visu vasaru,” Laiks, 26 November 1960, pages 1–2. See also Akmentiņš, Latvieši Albertā/Latvians in Alberta, page 33; Edgars Andersons, ed. Latvju Enciklopēdija 1962–1982, Rockville, Maryland: American Latvian Association, 1990, page 569; “Latvieši brīvajā pasaulē,” Laiks, 23 September 1960, page 4; and Half a Century of Soviet Serials 1917–1968. A Bibliography and Union List of Serials Published in the USSR, no date. Retrieved 8 April 2014 from http://www.loc.gov/ rr/european/bibs/smits.html.

81. “Death of Staff Member,” Library of Congress Information Bulletin, 1 December 1972, page 515.

82. “Vinipegas nodaļas latviešu soc. demokrāti un Vinipegas latv. sadr. biedrība,” Kanādietis, 30 November 1913, pages 165–166

83. J. A. S., “Vēstule Nr. 10, no Vinipegas, Kanādā,” Vēstules iz dzimtenes un svešuma un Latviešu Birojas programma, No. 2 (15 January 1920), page 11.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 7 August 2020