by E. Gwyn Langemann

Parks Canada, Calgary

|

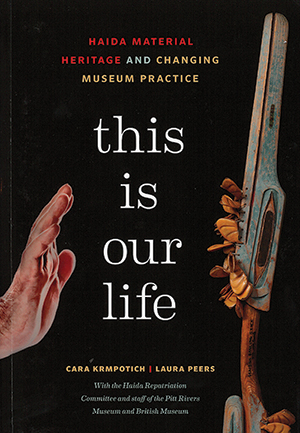

Cara Krmpotich and Laura Peers, with the Haida Repatriation Committee and staff of the Pitt Rivers Museum and British Museum, This is Our Life: Haida Material Heritage and Changing Museum Practice. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013, 292 pages. ISBN 978-0-7748-2541-2, $34.95 (paperback)

Objects are powerful. Beyond the impact of their physical selves, they are also archives, imbued with intangible meaning about the skills needed to make them, the situations they were used in, the stories they explicitly convey, and the deeper stories that underpin every culture. They may even be living beings, in need of care and nurturing. Ethnographic museum objects are loaded with all the heavy baggage of colonial relationships and cultural loss, but may also serve as a springboard for cultural renaissance in their living source communities. One role of museums is to bring people and objects together. In the past this has been for didactic reasons, but increasingly it can also be for mutual learning.

Objects are powerful. Beyond the impact of their physical selves, they are also archives, imbued with intangible meaning about the skills needed to make them, the situations they were used in, the stories they explicitly convey, and the deeper stories that underpin every culture. They may even be living beings, in need of care and nurturing. Ethnographic museum objects are loaded with all the heavy baggage of colonial relationships and cultural loss, but may also serve as a springboard for cultural renaissance in their living source communities. One role of museums is to bring people and objects together. In the past this has been for didactic reasons, but increasingly it can also be for mutual learning.

There is a growing literature examining changing museum practice as it concerns relationships with living source communities. This book is an example of one particular encounter, told with skill and understanding and from a variety of viewpoints. It details a meeting in 2009 between staff of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, staff of the British Museum, and a Haida delegation visiting a significant collection of Haida objects currently in the care of these museums.

Since the mid 1990s, the Haida Repatriation Committee has been researching Haida collections and vigorously pursuing repatriation of their ancestral remains from museums in Canada and around the world. Visits to these museums are also an occasion for the Haida to bring their living culture to the public in the host country, by putting on dances and feasts. In this case, the Pitt Rivers and British museums were ready to set up a longer-term relationship, and eager to learn more about the objects and how to care for them.

Many people were involved, and their perspectives are presented in their own words in multiple side bars dotted throughout the narrative. This kaleidoscopic approach will satisfy some readers and irritate others. I found myself longing to actually hear the multiple voices as a radio documentary. The overarching narrative, however, is written by two curators from the Pitt Rivers Museum.

The book is divided into three main sections: preparation for the visit, the moment of encounter, and reflections after the visit. Unusually for this sort of book, considerable attention is paid to the preparation stage; curators and conservators describe how they prepped and documented such a large collection, and the logistics and sensitivities of such a large group viewing. The Haida describe how they chose their delegation. The encounter is theoretically framed within the idea of establishing a contact zone, or a third space, in which people can set aside an unequal or polarized relationship and interact respectfully. Haida participants describe both the sorrows of encountering objects long lost to the community, and the joys of discovery. All find it surprisingly emotional. After the visit, visual and digital records are shared, and curators and conservators from the two museums visit the Kay Llnagaay cultural centre at Skidegate in Haida Gwaii. The hope is now to maintain the established relationships, to continue mutual learning, and eventually to arrange a loan of objects to the Kay Llnagaay. It is clear that all participants were changed personally and professionally by such an intense visit. It is less clear how the museums themselves were changed as institutions.

Peers and Krmpotich spend considerable energy defending the decision to allow the Haida to handle and even use some of the objects; rattles are shaken, hats are worn, gambling sticks are played with. For conservators trained to preserve items for posterity, this is a very large step. But part of their learning process is the realization that there are other ways of looking after items properly; some objects need to be sung to, fed, or handled to ensure their well-being. The authors also discuss changes to cataloguing methods, to bring in the commentary from the Haida. The “changing museum practice” referred to in the title seems to refer to such practices, that validate Haida knowledge as equal to curator knowledge. But changes to museum governance are, so far, very limited and can be at odds with the expectations raised by these newly-generated relationships.

I came to this review as an archaeologist, from a professional community that also grapples with questions of “whose past is it?” It is no longer possible to do an archaeological project on the Northwest Coast without serious and substantial involvement of the First Nations. Through their work during the establishment of Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, my archaeological colleagues at Parks Canada were instrumental in establishing a good relationship between the Haida Nation and the Government of Canada. The repository for archaeological objects from Gwaii Haanas is at the Kay Llnagaay museum, not with the larger Parks Canada collections. Archaeology, as one means of exploring the long relationship between people and the landscape, and illuminating their deep history, is important to many Haida. Museum objects are equally important.

Repatriation is given a very narrow definition by Peers and Krmpotich, specifically referring to human remains. “Knowledge repatriation” sessions like the one described in this book are increasingly common in the United Kingdom, but museums there are deeply uncomfortable with the concept of actual “object repatriations.” In Canada today, the relationship between museums and First Nations is profoundly different from what it was a generation ago, although it is still an evolving relationship. [1] First Nations are directly involved as curators and experts, museum objects have been repatriated through long-term loans, and communities have developed cultural centres to promote the reintegration of these objects. This is explicitly the goal of the Haida delegates too, but this outcome is not even considered as a possibility by Krmpotich and Peers. Imagining the future best museum they ask, “What would it be like if projects such as the Haida research visit were part of the regular, ongoing work of museums, rather than one-off special endeavours? What if such engagements were not seen as ‘hijacking the museum’ ... but were written into core future plans and institutional mission statements?”

An example of just such an integrated approach is the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, where First Nations participation is a formal part of ongoing museum practice. There is an explicit Memorandum of Understanding with the Kainai (Blood) Mookaakin Cultural and Heritage Society to promote and preserve spiritual doctrines and observances, along with language and other cultural practices. To support these goals the Glenbow has unconditionally repatriated several hundred sacred objects to various Blackfoot source communities. [2] Unconditional repatriation was a controversial strategy, but one of enormous importance to the communities, that led to a change in provincial legislation. Frank Weasel Head notes that things started to go right with the community once these objects were back home, and when people were again caring for these spiritual bundles. For the Glenbow, the unconditional return of objects was a strong moral imperative and has led to a lasting relationship between the museum and the communities on many fronts. It is no longer remarkable to have First Nations visitors using the Archives, or bringing their families in; Elders have been made Fellows of the Glenbow to honour their contributions, and Glenbow staff have been made honourary Chiefs and given names.

Laura Peers was mentored by Gerry Conaty early in her career, working with the Blackfoot on a project of “visual repatriation,” returning images of ancestors and objects. [3] More recently Peers facilitated the loan of a collection of Blackfoot shirts from the Pitt Rivers Museum to the Glenbow and the Galt Museum in Lethbridge, resulting in an encounter with the Kainai and Piikaani communities very similar to the encounter with the Haida. Blackfoot people greatly appreciated the chance to handle the shirts, but the shirts returned to Oxford. Frank Weasel Head asks, “If you don’t understand something, why keep it? When they are held in a museum, they aren’t in the community and they don’t fulfill their purpose.... We treat them as living things. They are here to help us, not just spiritually, but in our everyday life.” Weasel Head has enlarged his conception of repatriation over the years, coming to see it as not just bringing back sacred items, but as using the items to help with “a repatriation of a way of life that was taken away from us.” [4] Nadine Wilson echoes this bittersweet feeling, divided between gratitude that a Haida chief’s headdress is there in the Pitt Rivers for her to see, but then asking, “What are they doing here? This is such a waste! Nobody gets to see them. We can’t learn from them.”

Nika Collison notes, “Like us, [the people working in the museums] inherited the right and the responsibility to do things differently—to make things right.” The encounter was a respectful one, with everyone involved working very hard to make it a chance for learning and healing and a chance to turn any anger from the past into a positive energy. Some of the younger Haida write about how the objects they saw and handled have inspired their own creative energy; the Haida delegation made a point of including novice carvers and weavers as well as Elders and language speakers. Many of the participants write movingly about how fundamentally they were changed by the encounter.

At the end of this story, however, the objects are still at the Pitt Rivers and the British Museum. However interesting this encounter was, and however productive as a first step, access to the Haida objects is still controlled by the museum, and the relationship is unequal. The book’s cover shows a hand reaching towards a carved rattle, but not actually grasping it. What will it take for the Pitt Rivers Museum to move past visual and knowledge repatriation, and take the next step in a fully respectful relationship?

1. Victor Rabinovitch, “Making Amends; How reforming museum practices is helping revive aboriginal spirituality,” Literary Review of Canada, vol. 23, no. 5, 2015, pp. 3-4.

2. Gerald T. Conaty, editor, We are Coming Home; Repatriation and the Restoration of Blackfoot Cultural Confidence, Athabasca University Press, 2015.

3. Alison K. Brown, Laura Peers, and members of the Kainai Nation, Sinaakssiiksi aohtsimaahpihkookiyaawa; Pictures Bring us Messages: Photographs and Histories from the Kainai Nation, University of Toronto Press, 2006.

4. Conaty, We are Coming Home, p. 189.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 24 July 2020