by Sheila Grover and Greg Thomas

Winnipeg, Manitoba

|

This article is from the recently published book 100 Summers on Lake Winnipeg: A Resort History of Victoria Beach by Greg Thomas and Sheila Grover. In describing the history of the cottage experience at “VB,” the article looks at the layout of the original cottage lot grid, early cottage architecture and furnishings, as well as daily life and train travel to and from the lake. It is part of a larger popular history which traces the resort history of Victoria Beach from its inception to the present day. To purchase copies of 100 Summers, visit their website at www.vbhistory.ca. Eds.

For some cottage dwellers in the planned community of Victoria Beach the experience may not have been altogether positive. The original cottages are just that: modest, boxy and often old-fashioned, if not actually primitive. They are situated on lots 75 feet wide (23 metres) packed into busy avenues that churn with kids and adults, bikes and dogs. Crows wake you early in the morning. It’s so dark at night that you can’t see your hand in front of your face. You are not allowed to drive your car in the summer months. There are bats. There are skunks. Did we mention the bugs? The poison ivy?

But for those who share the founders’ vision, it is a little slice of heaven. Situated along the shores of Manitoba’s Lake Winnipeg, with white sand beaches, sparkling water and an infinite horizon, the summer resort is a leafy peninsula in an ancient boreal forest brimming with ecological diversity. Intense development of cottage lots along the winding lanes has created a community where socializing is made easy. Engaging in community life is as simple as choosing an ice cream cone at the Moonlight Inn, buying fresh bread at the bakery, and groceries at the general store. It means participating in kids’ games, bridge or yoga, playing golf or tennis, or simply dangling a fishing line over the pier—these are experiences we value. We appreciate the interaction with nature because it isn’t urban, it’s natural. It may not always turn out perfectly, as anyone with road rash from a night-time bike crash can tell you, but it’s how we like it, if only for a precious few days or weeks in the summer.

Auld cottage and yard at Victoria Beach, 1925

Source: Auld Family

The original cottage development, which is now defined by the restricted area where cars are not allowed in summer, evolved from a campsite on Pier Point and followed the shoreline north. As surveyed within the Victoria Beach Company plans, the cottage area formed a grid of eight avenues crisscrossed by three (later four) roads leading to beaches of the same name: Arthur, Patricia, King Edward and later, Alexandra, to continue the royal lineage. Connaught Beach was a later addition. This grid was laid over a horseshoe-shaped land form mainly looking west across the expanse of Lake Winnipeg. The area developed incrementally in response to the demand for cottage lots. Early on, Arthur Road was the primary axis to Sunset Boulevard. Running east-west, this road was the link from the permanent settlement to the east, right down to the shore at its western terminus. Arthur Road continued beyond 8th Avenue as a path running through thick forest to the local school and beyond to the year-round properties. It broadened to a wagon trail, then later a road and is now the final approach of Highway 59 and the entrance to the vehicle parking lot. Arthur Road crosses 8th Avenue, which runs due north and is a sectional boundary in the original purchase of the Company from the Crown. [1]

Roads were cleared from the dense forest on an ‘as need’ basis. If you examine the original plan, it appears that the avenues run straight on the grid but this is not the case. Winding roads were an integral part of the original vision of a picturesque country village. The roads were cut to accommodate heavy glacial erratic boulders (which can be seen on any avenue) and large clumps of trees to form gently wandering routes with as little loss of vegetation as possible. Local labourers did the heavy work, using hand tools and wagons pulled by horses. It was strenuous employment, best done by strong young men employed throughout the season under the direction of the Company. The roads themselves were pure sand by the time the crews were finished, and in dry periods they cast up a great deal of dust.

There were many wagons making deliveries in the beach during the 1920s, as well as Reeve Sprague’s own Model T Ford. To reduce the spread of dust, and to keep people safe, especially children, ‘inside paths’ were cut through the bush within the road allowances which had wisely been set aside along each block. The forest has reclaimed many of these paths, but vestiges remain in secret places between cottages. These small paths, and other informal trails developed by cottagers, acted as shortcuts to the water pumps and beaches. They stitch the community together and are well known to locals as ‘skunk paths’ or ‘witchy paths’.

Roads were oriented to the lake to facilitate access to the beaches and lake views. In the earliest years of development (1916 to the early 1920s) lots along Sunset, First Avenue and Arthur Road were acquired and cottages constructed. This was followed by the opening of the other avenues and, where they intersected with Sunset, one can still find some of the oldest cottages. Within the practical constraints of clearing the roads, individual lots were made available as new owners identified their choice of lot on the Company’s map, at a price point they were willing to pay. Hop scotching between the lots acquired, the Company owned extensive properties under the names of their brokers.

Donaldas: a quirky name for quirky little structures common in the early years of VB. Half-tent, half shed, they owed their origin to the military for field use. Much more comfortable than camping in a traditional tent, donaldas measured approximately 10 x 10 feet. They featured roofs of canvas and walls of beaverboard and screen, with 2 x 2 segmented framing over a raised wooden platform. They served new property owners for a summer or two before they could erect their permanent cottage. Unable to withstand a winter snow load, donaldas had to be collapsed in the fall but might later be refitted as bunkhouses. A few were later adapted with solid wood walls and have survived to the present.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

Once a lot was purchased, its new owners were allowed to camp there for a season. A few hauled in railway boxcars, while others erected half-tents with canvas walls over a raised platform, the iconic ‘donaldas’. This allowed the owners to arrange for the permanent cottage construction while enjoying their new summer property. Lots identified for new construction had to be cleared of enough trees, stumps and rocks for a site to build on, and the building footprint levelled. For the first three decades, the Victoria Beach Company controlled both the supply chain of building materials and the contracting of most cottage construction, which explains the similar look in many of the older cottages. Initially, most cottages were built of rounded logs, either tamarack or spruce, locally sourced and somewhat resistant to insect bores. Fortunately, many of these old beauties remain, scattered throughout the restricted area and sometimes disguised with a frame addition built over and around the log portion.

The next cottage genre to emerge was frame construction, under a hipped roof, and commonly made of B.C. fir brought by rail to the Company’s lumber yard near the railway station. This wood was economical, sturdy and highly adaptable. Frame cottages were constructed over a post-on-pad system well-suited to sandy soils and relatively easy to level if the cottage sags in one direction or another. Early cottages were generally small, simple in layout, often incorporating whimsical details and designed to accommodate future expansion. Shiplap exterior siding, fir partitions, three-inch fir flooring either painted or covered in ‘battleship linoleum’, stone or brick fireplaces and chimneys, and expansive casement windows, were typical design elements. A fancy entrance with stone steps was considered a design upgrade. Work was done by local crews clad in overalls who soldiered on without electric tools. Each rafter was sawn on the spot, each wall and fireplace built by hand; each outhouse dug deep using only a shovel.

Victoria Beach benefitted from the expertise of two main builders with their supporting crews. First on the scene was James Paulson, who arrived from Balsam Bay before the resort development took hold. Besides clearing the first roads, Paulson worked with contracted surveyors to lay out the cottage lots. James Paulson later turned over his business to nephew Oscar Paulson and Alex Jonsson, who both carried on building successfully for many decades. Another Company contractor in the mid-1920s forward was Albert Larson, a carpenter raised in Sweden where wood-working was elevated to a high level of craftsmanship. After building grain elevators as a young man, Larson worked on many cottages in the beach, lived on 8th Ave., raised his family here and participated fully in the local community. Following his death in 1979, he was buried in the VB cemetery. [2] Anyone fortunate enough to own an old cottage from these master builders can consider themselves lucky.

Several other builders also worked in the resort, but on a more limited basis. Even before the railway stopped running in 1962, the Company released its tight grip on real estate sales and rentals, as well as the supply of building materials. The construction business had developed new methods and materials resulting in a greater variation in cottage design in the post-war period. From the late 1950s onward, cottages remain almost exclusively wood frame construction but tended to be larger with features such as decks, bigger kitchens, living rooms and even bathrooms. Pre-fab units and factory-made components sped up building while keeping costs for recreational property accessible for many people. Decks and screened verandas came into common usage during this time.

Besides minimum lot dimensions, there were requirements defining a 30-foot setback from the road and 10 feet from the sidelines and rear of each lot. There was also a minimum standard of design, and latrines prescribed for each new cottage construction. [3] No guest houses were allowed nor any commercial structures, and only one single-family dwelling per lot permitted, although bunkhouses were tolerated as overflow sleeping quarters. Any outbuildings must be behind the cottage. National fire codes regulated the installation of wood stoves as well as the construction of fireplaces to safety standards which were overseen by the Municipality’s building inspector from 1919 forward. Roofs were likewise constructed to exacting specifications for snow load support. These regulations, placed as caveats on property titles by the Victoria Beach Company, were designed for the protection of the community as well as to insure an acceptable standard of building construction. The Municipality generally adhered to building codes as they were refined and upgraded since the early 1920s until formal municipal planning replaced them in the 1960s, and this has served the community well.

Outhouse / biffy / backhouse / outside closetIn 1927, provincial standards suggested ‘outside closets’ should be “constructed in a workmanlike manner, should be fly-proof and placed at the far end of lots. They are not to be nearer than 20 feet from any dwelling or other occupied buildings. The doors must be self-closing and the sills and bases should be well banked withearth to prevent flies and insects from getting into the closets. The seats should be provided with self-closing covers.” |

In the 1920s, lots could be purchased for $250 in many avenues in the beach. A simple cottage might set a family back upwards of another $300 to $500. While these prices seem laughable today, they were not in those days. Banks had little interest in providing mortgages for summer residences but the Company was usually able to offer building loans. For the cottage-owners themselves, recreational property was a major investment that required careful saving. Cottages were frequently rented out to offset the cost, arranged through the Victoria Beach Company’s office at 317 Portage Avenue in Winnipeg or in the Company’s office at the beach.

In the first four decades of resort development, the Victoria Beach Company’s control of the supply chain even impacted the choice of paints available to cottage owners. Colour options of the durable lead paints reflected availability, or perhaps the rural roots of the founders, where farm colours in primary shades could brighten a yard over dreary winter months, or help to identify the barn or outbuildings in poor weather. Other cottages wore the brooding industrial maroon of the CNR line, mute testament to their owners’ place of employment. Once cottager owners had access to a broader palette, many responded with variations of earthy shades in colours that blend with the natural environment, while others kicked it up with saturated hues that pop in the sunshine and contrast with the verdant surroundings.

Cottage living room, 1940s.

Source: Beech family

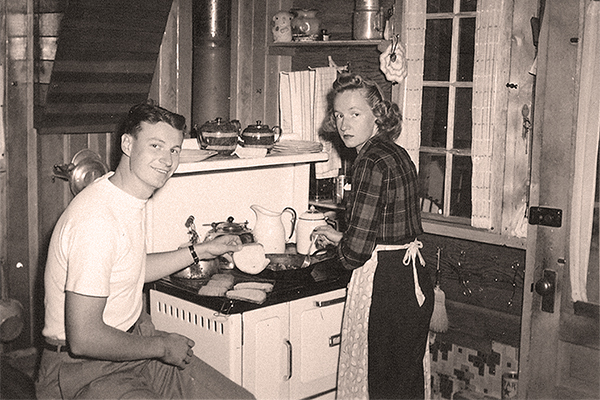

Cottages consisted of three distinct zones: a kitchen/eating area with a cook stove, a living area and sleeping quarters. A screened veranda was a coveted luxury, perhaps added later, and brought the outdoors in, minus the mosquitoes. Bear in mind that because people usually had only two weeks vacation and the concept of recreational property was new, seasonal cottages were occupied by owners only a limited number of days each year. As most cottage residents lived quite simply, cottages were modest in scale and features. Early cottages were fitted out with basic furnishings, possibly purchased new or recycled from their city homes. A certain raffish ambience was appreciated and possibly even cultivated. Mismatched crockery, diminutive metal beds, dark, lumpy furniture and the ubiquitous ‘Toronto couch’ were the norm but no one thought much about it. Woe betide any guest who sniffed at the decrepit furnishings because traditions set in very early and cottage owners were loath to change.

A novelty postcard illustrated the young and old who lived, worked, and played at Victoria Beach through the years.

Source: Rob McInnes

If there is one style of furniture that could be said to typify Victoria Beach early on, it would be the sturdy oak Craftsman style, which was readily found in the Eaton’s catalogue for the first decades of the cottage boom. White wicker as well captured the breezy (and suggestively British) style of a summer home and was both economical to purchase and inexpensive to ship. Open shelving on built-in cupboards was common, allowing the artistic arrangement of a few nice pieces. Paintings were modest in scale and often depicted pastoral scenes or references to First Nations life in hopelessly romanticized settings. The Union Jack often fluttered in regatta flags or was tacked to the wall, this in the days before there was a Canadian flag. Aladdin lamps, fuelled by kerosene, perched on small ledges and side tables. Brass hammered plates, horse harness tack and other relics from rural days past were popular. Fireplace tools had to be functional and sturdy and were usually jammed into woodboxes by the stove or fireplace. Hooks or even nails pounded into the wall stood in for storing clothing in lieu of full closets. Metal hangers responded to the marine micro-climate by rusting and staining textiles left on too long.

What’s on your window ledge?bones of fish or birds and small mammals |

As cottages were occupied almost exclusively in the summer months, cottage windows opened wide, integrating structure with landscape and ushering in the cooling breezes. Windows were fitted with good quality screening against the many insects. In response to the warm weather, interior partitions stopped short of the ceiling to promote air flow and, effectively eliminate privacy. Cooking was done on the wood stove, which had to be fired up frequently even on the hottest days. Stoves and fireplaces also provided welcome warmth when the weather turned. A wood pile could be found in the rear of every property. Some cottages had cold-storage pits under the kitchen or out the back door, but most cottagers relied on regular ice delivery, hauled in from the wagon or truck with giant tongs, to keep their iceboxes cool enough to preserve perishable food.

Water reached the cottages in a number of ways. Initially people had to haul it from the lake in pails. As early as 1920 the Municipality built a pumphouse at the foot of 8th Avenue to draw water from the lake. [4] Lightly treated, this water flowed through a network of pipes to public taps, to be used as wash water. Deep cisterns, found in several locations throughout the beach, were filled with drinking water that individuals pumped to the surface and into the pail. Eventually, water was piped to individual properties and hooked up for a fee plus an annual rate. Hauling pails of water from public pumps was a job for kids when possible, but meeting neighbours at the pump for a chat was also a welcome event. Many cottages also had eavestroughs to capture water from the roof into a big galvanised metal rain barrel located at the rear of the cottage. A line and tap ran this water into the cottage. While not fit to drink, stored rainwater was used to wash clothing and dishes and was especially wonderful for washing one’s hair. Outhouses, often called biffies, provided sanitation for all but a tiny number of cottages where a bathroom was installed.

Laundry, particularly for those with babies in diapers, remained an onerous task. A few cottages had hand-cranked wash tubs in the early days, later followed by an array of decrepit Maytag ringers featuring heavy rubber rollers to trap fingers. For those who could afford it, there was the Rumford Laundry Service available well into the 1940s, with local pick-up and delivery. Quinton Cleaners and Launderers, locally owned by the Quinton family, also advertised their services in the city. Most families, usually women, heated water in a reservoir or big pot on the wood stove and used the kitchen sink to hand wash the laundry. Swimming remained the best way to keep clean. Outdoor showers, much coveted in Victoria Beach, continue the joyous tradition of bathing in the great outdoors.

Many of the best services came right to the door. Pedlars sold a healthy variety of local products such as fresh berries, vegetables and pickerel fillets. Crescent Creamery brought milk products to the cottages early each morning. Deliveries were made in horse-drawn wagons, a delight for city children who were allowed to climb aboard for the trip along their own block. Wood and ice delivery were the domain of the older teens, working for the Andersons and Ateahs.

With all the dray services, there were many horses within the district, and a good number of cows as well to provide milk for the local families. The livestock needed pasture and stabling, especially in summer when they were working hard. Land at the foot of Bayview could be counted on as pasture most years, behind makeshift fencing, with children collecting their own cows for milking each morning and evening. The marsh immediately south of here dried out so much in the 1930s drought that all the land from what is now Pelican Point to the rail line became a vast meadow for grazing the livestock. In the shoulder seasons, livestock was often left to roam, to find their favourite areas, which was often on the old RCAF field.

While fire is a critical threat to any forested community dominated by a building stock of wood, for most of the year cottages slumbered within a closed loop of security. From cottage closing, as early as September when the trains went to a reduced schedule, until opening in May or June, there was little threat to the buildings. The roads were not plowed in winter and the trains were infrequent. There were neither electrical lines to catch fire nor water lines to freeze and flood. Break-and-enters out of season were rare. While storms can cause trees to crash through a roof or flatten an outbuilding, the results would likely be localized and would not cause a fire. That is not to say that cottages were immune to natural forces such as lightning, or human mishaps related to smoking or overheated stoves.

Stone FireplacesMany VB cottages feature beautiful stone fireplaces. In new construction, the fireplace would be built first to anchor the cottage erected around it. Skilfully constructed from weathered rocks gathered on the beach, the fireplaces are functional time machines as the softly-rounded rocks had long tumbled in sand and ice in the lake. The specific sources of the fireplace rocks were proprietary and the stone masons seem to have toiled anonymously during the cottage contractors’ formative years. In the post-war period, John Ateah specialized in stone fireplaces crafted with great skill and an artistic sense of colour and placement. |

As mice try their utmost to gain entrance to cottages in the fall, the discovery of their droppings or mouse damage in the spring is common. Birds and squirrels occasionally descend open chimneys and cannot retreat, which can wreak havoc over a winter. One family opened up their cottage one winter day, surprising a pine marten that had found a comfy spot on the top bunk where it was dining on soda crackers. When the humans suddenly appeared, the marten slithered up an interior wall and beat a hasty retreat. Skunks are prone to dig nests for their litters under cottages and bears are especially fond of barbeques and garbage bags, or pet dishes innocently left on a deck. Wasps may nest under eaves and carpenter ants find the nice, dry cottage wood irresistible. The closer a cottage is to the lake, the denser the infestation on its screens by fishflies, which arrive every July all in a rush. Cottage dwellers may feel they walk a line between communing with nature and being overwhelmed by it.

Murray Auld feeding a chipmunk, 1941

Source: Auld family

Land around the lake peninsula undulates gently, depositing soil here and there over the sandy loam and generating a diverse array of trees and bush that changes from block to block. After clearing vegetation for construction, cottagers later set about to shape their own landscape. Letting a bit of sunshine into the lot was understandably a priority. As roaming cattle and horses remained an issue for many years, those who put in gardens often protected them with fences and gates, as anyone coming from a farm would do. Trees and bushes were isolated and pruned into borders and features, paths and flower beds were developed and architectural elements such as stone birdbaths, pergolas and woodsheds erected. Courts for playing croquet and badminton may eventually be installed, or a basketball hoop erected. The larger glacial boulders tended to stay where they were while growing luxurious coats of lichen and moss. Hammocks, swung between trees, symbolized a leisure that contrasted starkly with city life.

Travelling to the beach on the train had its advantages. You took your belongings by suitcase or trunk, or in a big roll secured with rope, to Winnipeg’s Union Station. While baggage could be brought and stowed in advance, passengers arrived to meet the scheduled departure in a streetcar, taxi or automobile. The station bustled with activity as trains arrived and departed, carrying excited passengers of all ages. The fare to the beach was set for a round-trip, but canny passengers could sell their return ‘stub’ if there was a willing buyer on the other end. While relaxing to a point, the ride north took place in the oldest rolling stock that the CNR owned: ‘rattlers’ that bumbled along at low speeds behind huffing coal-burning steam engines, with seats in the railway’s sombre maroon upholstery that carried a particular cachet from ages past.

Meeting the train at the Victoria Beach station, 1925.

Source: Auld family

The train’s first stop was Transcona to collect railway families who travelled on passes. After crossing the Red River, it chugged along to East Selkirk, Libau and Scanterbury [5] (with stops as needed) before arriving at Grand Marais and Grand Beach, where some of the cars were side-tracked. Following possible stops at Belair, Hillside and Albert Beach, the train moved slowly along the unstable road bed through the marsh, and arrived, bell clanging, in the Victoria Beach station up to about five hours after departure. ‘Through trains’ were much preferred in the summer months as they reduced travel time to about two and a half hours. ‘Newsies’ sold papers, candy and cigarettes in the coaches and on the platform. Cottager Dr. James Mitchell recalls the train ride as great fun for children, but adds one sobering memory. Kids would poke their heads out the windows, enjoying the breeze until a hot coal cinder from the steam engine blasted them in the face. [6]

Large baggage carts jostled on the platform to unload the luggage and commercial supplies. Local transfer services awaited the carts adjacent to the platform in their wagons and later, their trucks. Meanwhile the engineer would oil parts of the steam engine, and refill its water tanks from the wooden tower up the track. Then, if all went well and the engineer was in a good mood, children were allowed in the passenger cars. The train backed into the ‘Y’ siding in the bush past Bayview to turn around for the return journey. Excited kids were theoretically obliged to sit properly on the seats and could drink water from white cone-shaped paper cups. This was the northern terminus of the CNR line; its ‘End of Track’ sign was anchored in a pile of cinders under the present-day spruce tree near the play structure on the Village Green.

The train schedule regulated the daily rhythm of life at the beach. The VB railway station, painted white with green trim, and built to a CNR standard plan, was identical to the one in Grand Beach. It featured a passenger waiting room and a large baggage handling area, all beneath broad eaves. The station master’s rooms on the second floor included a gable window that offered a clear view of the track. A pyramidal roof covered the station and gave it a dynamic, welcoming appearance. The broad wooden platform was the gathering place where guests and family members arrived and departed, where plans were made and services arranged for. Immediately across from the platform and its lovely flower garden were the stores and the commercial services. It was here that one could arrange for wood or ice delivery, have an ice-cream cone, pick up groceries, meat and bakery goods, order wood or shingles and arrange for it all to be delivered. Friday night’s Daddy Special train turned into Sunday night’s sad farewell, at least for the working man.

Beech family kitchen with wood-burning stove, 1940s.

Source: Beech family

During the summer months, dawn comes early, and the birdsong begins in earnest. ‘Sleeping in’ may not have been so much a foreign concept as an impractical reality in a small cottage with half-walls. If morning coffee or toast was to accompany breakfast, the stove had to be lit. Hauling water for dishes and laundry, restocking the wood pile, sweeping out the sand and rinsing the straw from the ice block delivered to the back door were routine jobs. While meal preparation, getting groceries and mail, cottage maintenance and repair, chopping and piling wood could fill a cottager’s morning or be shared among assorted family members, there was usually plenty of time for leisure as well. Adults may garden or pick berries, take a canoe out on the water, explore, read or pursue hobbies. Kids often had many playmates and a range of options for activities. The beach itself was a great gathering place for young and old, as it provided shared space for visiting, sunbathing, playing, swimming and beachcombing. As cottagers settled into their summer retreat, it was hoped that their skin bronzed, their feet toughened, their legs strengthened and their minds relaxed.

First generation cottage development in Victoria Beach took place during Manitoba’s years of liquor Prohibition from 1916 to 1923. [7] Definitely the resort investors never expressed any predilection for a beer parlour or a bar within the beach. While some of the summer population would be earnest teetotallers, alcohol was part of many cottagers’ social interaction. ‘Happy hour’ became a popular event possibly after returning dry from an afternoon swim or a round of golf.

While weekday dinners were mostly simple affairs, the weekend might feature a roast from Kilpatrick’s Butcher Shop. A useful array of tinned foods from the local grocery stocked kitchen cupboards. Cooked food was prepared on the stove, which required someone, usually the woman, to come up from the beach to light it, stoke it to the right temperature, prepare and put on the meal. Barbeques did not make an appearance until the 1960s although some fire pits did exist. When the dishes were done and the stove burned down, it was time to light the kerosene lamps, from fuel purchased at the grocery or lumber yard. Aladdin lamps came in a variety of styles using combustible fuel and textile wicks. They cast a beautiful golden glow but it was a struggle to read by them. The weekly cleaning of soot from their glass chimneys was a kid’s job. Evenings were ‘grown-up time’ on the veranda, when older people and parents could kick back, visit and perhaps have a game of Scrabble, a singsong or a game of cards.

IceBefore electric refrigerators, cottagers kept perishable food cool with ice. Kitchen iceboxes held ice within enamel compartments lined with sheets of zinc. As the ice melted through the day, it dripped into a pan underneath that needed to be emptied frequently. Harvesting ice was a dangerous and labour intensive business undertaken by local men during the winter. Sam Ateah’s memoirs recall sawing huge blocks of ice from the lake, hauling them on sleighs, and storing the ice packed in sawdust topped with straw in the ice house at the foot of 8th Avenue, or at the Ateah icehouse at the northeast corner of the Ateah quarter-section. Sam and his helpers (teen-age boys) delivered the ice on their daily rounds, for many years on a horse-drawn wagon and later on his truck. Ice deliveries were done in the morning, followed by a sweep-out before picking up cartage from the noon train, and then on to wood (and later propane) deliveries. By the late 1940s, the Department of Health monitored the storage and handling of ice for public health, forcing one local ice house operator to relocate the ice house farther away from a cattle barn for fear of contamination. |

Taking tea with one’s friends remained a pleasurable pastime for many, but ‘tea’ could translate into a cold beer, a sandwich on the lawn or even a gin and tonic. Because access to a summer place was much less common, people staying in cottages were often generous in sharing lake time with city friends and extended family. This was especially true during the war years when cottagers opened their places to servicemen on brief furloughs and to the families of troops serving overseas. Perhaps it was easier to have guests come for a stay by train (this, arranged by post or phone calls within the city). Perhaps life was kept more simple and expectations more modest.

One young girl and her two sisters were each allowed three or four friends to stay in the cottage for ‘their week’ to share in a summer holiday with children who would not otherwise get out of the city. [8] Tents on the lawn could accommodate overflow and provide young children with their first camping experience. Bunkhouses were the domain of teens; sneaking out at night signalled a passage into one’s teenage years. Beach friendships tended to be firm and intense while beach romances sometimes evolved into beach marriages. Beach rivalries, especially with local teens, could be volatile and sometimes violent. Where teens may rough it up in the Clubhouse yard after the dances, adults entered pitched battles on the baseball diamond on Sunday nights, locals against summer residents, after the train had departed. [9]

Rainy days may refresh a dusty summer but too many in a row drove parents and kids to distraction. Books, puzzles, hobbies, crafts, games, playing instruments, building forts and playing cards wiled away many hours in the years before TV and electronic games. People were more inclined to make their own fun, and some of that was creative, verging on eccentric. Weekend warriors on 4th Ave. strung rope across Alexandra Road for their games of ‘caveman tennis’. Local teens formed a glee club, the ‘VB-ites’, with performances at each other’s homes or the Clubhouse. Elaborate ceremonies and plays were staged, with roles for children and pets.

Sunny days provided numerous distractions. Walter Thomas, and later the Trainor’s Shamrock Ranch, offered riding horses for hire. Captain Thomas also piloted excursions to Grand Beach or north to Black River on his sloop, the Valtannis. Grey-bearded labrador Trixie and her family hosted annual dog parties where neighbouring dogs had to wear costumes and their excited young humans were treated to popsicles and cookies. ‘Golf ball runs’ involved building serpentine routes with drawbridges and trapdoors down the shoreline banks. Bird-watching and star-gazing seemed to happen spontaneously. Exploring on foot or perhaps on bikes is as likely today as it was in summers past. Bonfires on the beach were popular for late-night gatherings for teens, and skinny dipping just might follow.

Postcard of the Patricia Beach slide, 1920s.

Source: Mark Stople

Then, when day is done, cottagers young and old find their way to bed and sink into the darkness. When there was little moonlight, and before electric lighting, the district grew extraordinarily dark and devoid of most human noise. Lake breezes ruffle the leaves and stir the waves, in a range of intensity up to almighty winds that sway the treetops and pounding surf that can be heard throughout the peninsula. The birds begin early.

During the railway era, most residents of the resort community were gone by the end of August to pick up their city lives. Kids returned to school and parents, presumably refreshed from their holidays, settled back into their daily lives. Few cottages were used beyond the Labour Day weekend. Closing down the summerhouse became an annual ritual of individual servicing: removing the foodstuffs, securing windows and doors, possibly with shutters, draining any waterline and taps, blocking the chimney and storing the bikes. The wagon or truck was summoned to load the cargo and reluctant cottagers for the journey to the train station to end the season for the ‘summer people.’

1. Section 10 Township 20 Range 7E, Department of the Interior Lands Patent Branch, Fiat for Patent 98997, 31 March 1910.

2. From the Beaches to the Falls, John Albert Larson, 1888–1979, p. 397–98.

3. Rural Municipality of Victoria Beach (RMVB), Minutes of Council, By-Law 9, 1919, and 39, 1923.

4. RMVB, Minutes of Council, 1920. Locations for water wells were chosen by a government expert hired by the municipality.

5. See advertisements in the Manitoba Free Press, June to September, 1916–1925.

6. James R. Mitchell, “311 First Avenue: Some Personal and Happy Memories of Life at Victoria Beach, 1921 to 1960”, a personal memoir.

7. George Siamandas, “Manitoba Bans the Bottle—The 1928 Liquor Act”, Time Machine. Siamandas.com.

8. Ella McGregor Carmichael, oral interviews, 2012.

9. George and Dan MacKay and Allison Bloomer, oral interviews, 2012.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 26 September 2021