by Diane Dodd

Parks Canada, Gatineau, Quebec

|

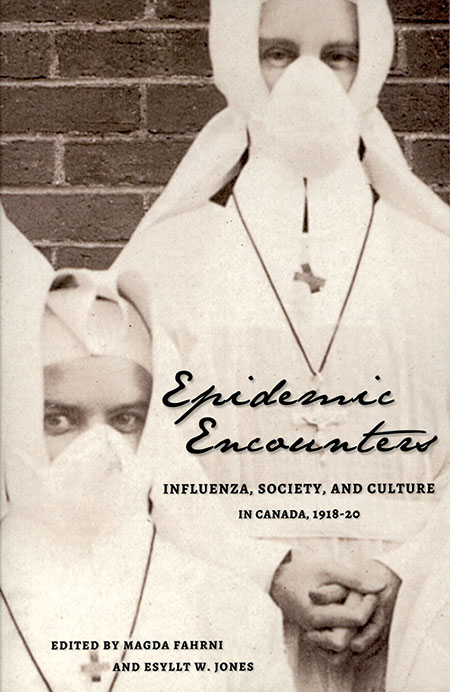

Magda Fahrni and Esyllt W. Jones, eds., Epidemic Encounters: Influenza, Society, and Culture in Canada, 1918-20. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012, 290 pages. ISBN 978-0-7748-2213-8, $34.95 (paperback)

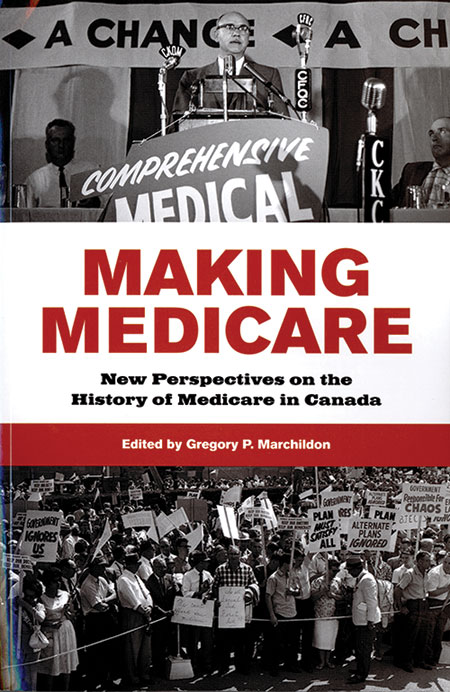

Gregory P. Marchildon, ed., Making Medicare: New Perspectives on the History of Medicare in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012, 336 pages. ISBN 978-1-4426-1345-4, $39.95 (paperback)

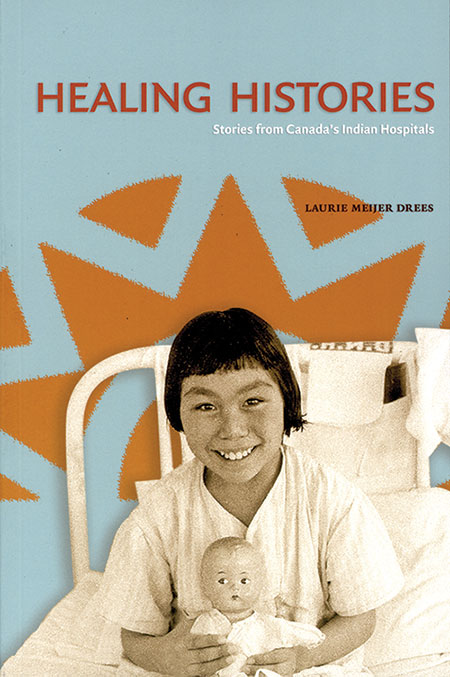

Laurie Meijer Dress, Healing Histories: Stories from Canada’s Indian Hospitals. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2013, 244 pages. ISBN 978-0-88864-650-7, $29.95 (paperback)

All three of these new volumes contribute to our understanding of the history of health care in Canada, particularly the way that social, political and eco-nomic factors impact the health of Canadians. Magda Fahrni and Esyllt W. Jones’s collection, Epidemic Encounters: Influenza, Society, and Culture in Canada, 1918-20 provides a nuanced and multi-faceted exploration of a long neglected topic in Canadian historiography. Like many historians, I came to an interest in this pandemic through the porthole of the First World War. In researching the commemoration of some sixty military nurse/war casualties, at least a third of whom had died from the flu, I sought in vain for any definitive treatment of the topic in Canada. Why had this pandemic, one of the worst in modern history, been so long draped in obscurity? The most obvious answer is the war itself. Happening at the end of a horrific conflict that killed over 60,000 Canadians, the flu seemed to add yet another tragic footnote to that sad story. The postwar rush to commemorate the soldiers, who in the nationalist language of the day had made “the supreme sacrifice,” perhaps sapped Canadians of their will to mourn the flu’s victims. Soon the Great War was being portrayed as a turning point in Canadian nation building, making flu deaths somewhat ordinary and unheroic. In a field long dominated by the anecdotes of popular history, this volume on the Spanish flu pandemic in Canada goes a long way toward filling a major gap in the literature.

All three of these new volumes contribute to our understanding of the history of health care in Canada, particularly the way that social, political and eco-nomic factors impact the health of Canadians. Magda Fahrni and Esyllt W. Jones’s collection, Epidemic Encounters: Influenza, Society, and Culture in Canada, 1918-20 provides a nuanced and multi-faceted exploration of a long neglected topic in Canadian historiography. Like many historians, I came to an interest in this pandemic through the porthole of the First World War. In researching the commemoration of some sixty military nurse/war casualties, at least a third of whom had died from the flu, I sought in vain for any definitive treatment of the topic in Canada. Why had this pandemic, one of the worst in modern history, been so long draped in obscurity? The most obvious answer is the war itself. Happening at the end of a horrific conflict that killed over 60,000 Canadians, the flu seemed to add yet another tragic footnote to that sad story. The postwar rush to commemorate the soldiers, who in the nationalist language of the day had made “the supreme sacrifice,” perhaps sapped Canadians of their will to mourn the flu’s victims. Soon the Great War was being portrayed as a turning point in Canadian nation building, making flu deaths somewhat ordinary and unheroic. In a field long dominated by the anecdotes of popular history, this volume on the Spanish flu pandemic in Canada goes a long way toward filling a major gap in the literature.

It seems appropriate that the collection should begin with Mark Humphries’ article detailing the role that the military played in hastening the spread of the disease across Canada. With a disregard for the health of civilians normally seen only in national emergencies, military authorities sent a special force destined for Siberia by train, from east to west. Filled with sick soldiers, it left the disease behind in the communities it passed through. As this and other articles in the collection note, the military continued to enforce conscription at the height of the pandemic, despite public protests. Humphries also looks at the public health legacy of the pandemic. While influenza was not initially a reportable disease, it soon became one, and other new public health measures were put in place in its aftermath. With a similar focus, Heather MacDougall compares the Spanish flu pandemic with the 2003 SARS epidemic, noting that the Spanish flu served as a catalyst for the establishment of the Federal Department of Health in 1919, and the SARS epidemic led to the creation of the Public Health Agency of Canada in 2004.

This collection breathes much-needed fresh air into the stale notion that the Spanish flu was no respecter of socio-economic class, place of residence, or ethnicity. Indeed its history reveals the opposite. For example, Francis Dubois, Jean-Pierre Thouez and Denis Goulet demonstrate differentials in mortality and morbidity according to class, region and ethnicity in Quebec. Similarly, D. Ann Herring and Ellen Korol analyze flu deaths during the autumn of 1918 in two areas of Hamilton, Ontario, showing that those living in the industrial, working class wards in the northern part of the city were more likely to die from influenza than those who lived in the more affluent wards in the south. Not surprisingly, Aboriginal populations were the hardest hit, as Karen Slonin shows in her analysis of two Manitoba communities: Norway House and Fisher River. She finds that Cree inhabitants of Norway House had a mortality of 18%, and Fisher House 13%, compared with a death rate of only 0.6% among non-Aboriginal Canadians. Disruption of marginal subsistence activities and lack of basic care—someone to keep the fire burning and provide food and water—aggravated the impact of the disease.

This collection breathes much-needed fresh air into the stale notion that the Spanish flu was no respecter of socio-economic class, place of residence, or ethnicity. Indeed its history reveals the opposite. For example, Francis Dubois, Jean-Pierre Thouez and Denis Goulet demonstrate differentials in mortality and morbidity according to class, region and ethnicity in Quebec. Similarly, D. Ann Herring and Ellen Korol analyze flu deaths during the autumn of 1918 in two areas of Hamilton, Ontario, showing that those living in the industrial, working class wards in the northern part of the city were more likely to die from influenza than those who lived in the more affluent wards in the south. Not surprisingly, Aboriginal populations were the hardest hit, as Karen Slonin shows in her analysis of two Manitoba communities: Norway House and Fisher River. She finds that Cree inhabitants of Norway House had a mortality of 18%, and Fisher House 13%, compared with a death rate of only 0.6% among non-Aboriginal Canadians. Disruption of marginal subsistence activities and lack of basic care—someone to keep the fire burning and provide food and water—aggravated the impact of the disease.

Serious academic study of the Spanish flu has also been limited by the relative lack of available medical options—there were no heroic discoveries, and no great men or women of science who appeared with a magic pill or vaccine to defeat it. Indeed, ordinary nursing care, which as Linda Quiney points out was often provided by untrained nurses, was arguably the most effective remedy. As individuals fell ill with the flu, which hit otherwise healthy young people the hardest, pneumonia and/or other complications often ensued and led to death, sometimes in days. But first, patients exhibited frightening, un-flu-like symptoms, such as cyanosis (bluish discoloration due to lack of oxygen in the blood) and bleeding from nose, ear, and eyes. Long-term rest following the initial onset of the flu was critical to recovery. While difficult for the poor and economically marginal, rest was nearly impossible for nurses and doctors who often worked to the point of exhaustion caring for the sick. As well, they were continually exposed to the disease, thus suffering a higher mortality rate than that of other Canadians. Several authors also tackle the social meanings of the disease, adding a richness and complexity to the collection. Magda Fahrni examines letters from members of the Montreal public in which they express everyday concerns such as keeping businesses open in order to make a living. Others expressed their opposition to the continued recruitment of troops during the pandemic. Utilizing the concept of modernity, Mary-Ellen Kelm analyzes the “flu stories” of her own family, and of other, particularly Aboriginal, British Columbians. Esyllt Jones explores one family’s renewed interest in spiritualism as they coped with the loss of a child, attempting to speak to her through séances.

The Spanish flu was one of a number of events that con-vinced many Canadians of the need for improved access to basic medical care. A collection of essays, edited by Gregory P. Marchildon, contributes to a better understanding of the history Canadian health care by exploring the political achievement of Medicare. This book adds to the historiog-raphy of a topic long dominated by Malcolm Taylor’s 1987 work, Health Insurance and Canadian Public Policy: The Seven Decisions that Created the Canadian Health Insurance System. It also takes its place among recent explorations of social programs such as old age pensions, mothers’ pensions, and unemployment insurance, which were also shaped by the quintessentially Canadian wrangling between federal and provincial governments.

The Spanish flu was one of a number of events that con-vinced many Canadians of the need for improved access to basic medical care. A collection of essays, edited by Gregory P. Marchildon, contributes to a better understanding of the history Canadian health care by exploring the political achievement of Medicare. This book adds to the historiog-raphy of a topic long dominated by Malcolm Taylor’s 1987 work, Health Insurance and Canadian Public Policy: The Seven Decisions that Created the Canadian Health Insurance System. It also takes its place among recent explorations of social programs such as old age pensions, mothers’ pensions, and unemployment insurance, which were also shaped by the quintessentially Canadian wrangling between federal and provincial governments.

The collection’s greatest strength may be in detailing the many lesser-known precursors of national health insurance in provinces other than Saskatchewan—and in demonstrating that there was indeed nothing inevitable about the form that Medicare ultimately took. It is with some reason that most Canadians associate the history of Medicare with Saskatchewan where economic depression, drought, and a small, geographically dispersed population accented the need for public funding in support of medical care. Aleck Ostry traces Medicare’s history from Saskatchewan’s early 20th-century Municipal Doctors’ scheme and early programs of hospital financing, to the first provincial hospital insurance plan created at the end of the Second World War. Following the inauguration of similar programs in other provinces, a national hospital insurance program was created in 1957, followed by an insurance plan covering medical services in 1966. Through the story of the Swift Current Health Region, C. Stuart Houston and Merle Masse link the development of Medicare to the “famous co-operative spirit of the people of Saskatchewan” (p. 145). Still in Saskatchewan, Gordon Lawson examines the “myth” that doctors’ protests, culminating in the 1962 doctors’ strike, led the Saskatchewan CCF to capitulate to their demands, thereby entrenching fee-for-service payment in Canada. The authors take a step back in time, arguing that as early as 1945 the Saskatchewan CCF ignored recommendations from its own Health Services Planning Commission. They did so in the interests of political expediency, and as the authors argue, were never committed to placing doctors on salary, although their counterparts nationally, and in Ontario, were.

Focussing on the political and policy aspects of the Medicare story, Penny Bryden examines the inner workings of Lester B. Pearson’s Liberal Party who developed Medicare as a campaign platform while in opposition. They later implemented the measure as a single-payer plan rather than permitting the participation of private insurance carriers. In doing so, they incurred the wrath of Ernest Manning in Alberta and W. A. C. Bennett in British Columbia. As Robert Lampard notes, Alberta’s Hoadley Commission (1932-1934) established by the United Farmers of Alberta, called for a plan with local control and provincial subsidies, and contributory/voluntary as opposed to universal/compulsory coverage. Although influential, the Commission’s recommendations were never implemented by Manning’s incoming Social Credit government, due to the need to comply with federal cost-sharing conditions. In British Columbia, as Marchildon and Nicole O’Byrne note, the health insurance system evolved under the Bennett government: from a voluntary system with private, non-profit insurers to the federal universal, single-payer system.

This collection also provides a nuanced and detailed account of other precursors to Medicare, that is, the models not implemented. These stories serve as a needed counterweight to the iconic status of Saskatchewan as the “birthplace” of Medicare. At the national level, Heather MacDougall chronicles an early attempt at establishing health insurance by J. J. Heagerty of the federal Department of Health, who sought to combine funding for public health (preventive medicine) with diagnostic and treat-ment services. However, in working too closely with the Canadian Medical Association and neglecting the voice of workers, farmers and other supporters of health insurance, the scheme was unable to overcome the inevitable federal- provincial hurdles. Most of Medicare’s younger siblings grew up amid the harsh realities of local, geographically isolated communities. For example, as Gordon Lawson and Andrew F. Noseworthy note, Newfoundland established its own cottage hospital system in the 1930s, staffing hospitals with salaried physicians, and housing nurses in these buildings. This system in turn had roots in earlier efforts by the Grenfell Mission and Newfoundland Outport Nursing and Industrial Association (NONIA) to provide medical and nursing care to residents of the outport communities thinly stretched along Newfoundland’s extensive coastline. In a somewhat later period, in Quebec, Aline Charles and Françoise Guérard look at small, private, for-profit hospitals which were allowed to function in a contractual arrangement with the government through the 1960s and 1970s, after the introduction of hospital insurance.

Adding colour to the debate on Medicare, Felicity Pope analyzes political cartoons on the topic from the end of the Second World War until the introduction of the Canada Health Act in the 1980s. The collection concludes with fascinating personal accounts by political leaders, campaigners, a physician, and a researcher who fought to bring Medicare into being. Their testimonials speak to the acrimony surrounding Medicare in general and the 1962 doctors’ strike in particular.

Laurie Meijer Dress, in Healing Histories: Stories from Canada’s Indian Hospitals, examines the “healing histories” from Indian Hospitals run by the federal Department of Indian Affairs from 1945 to the 1970s. This social history, relating primarily to long-term tuberculosis patients, tells the story of the hospitals through the voices of nurses, the institutions, patients (many of them children) and their families. Their stories give expression to the fear, alienation, and familial and community disruption that Aboriginal patients often experienced due to the long-term hospitalization that was deemed appropriate for the treatment of tuberculosis prior to the implementation of antibiotics. Dress and her interviewees make the point that the hospitals, in separating children from their families, communities, and culture, effectively served the same purpose as residential schools in trying to assimilate Aboriginal children into the dominant white Euro-Canadian culture. Dress and some of her interviewees point a finger at the federal government for using hospitals to this end. While the book shows us that many patients, long separated from families and communities, never returned, there is no overarching portrayal of victimization. For example, the stories include several patients who did return to their communities and found improved health through traditional Aboriginal medicine. Other patients grew up and took work in local communities, and/or in the hospitals themselves, a few even managing to obtain health-care training.

The patients’ voices constitute the strength of the book; however, the author could have featured them more prominently and distinguished them more clearly from those of nurses and other hospital personnel, which are scattered throughout the book. Indeed it is not before the second half that one finds an actual account by a patient. Nurses’ voices, primarily those of Aboriginal nurses, are certainly of interest, but their perspective is quite different from that of the patients. A thematic approach organized around the content of the stories might have provided greater insight into their respective experiences. Instead, the author has organized the interviews, which she has supplemented with introductory notes, into six sections in accord with the institutional relationship of the interviewees. As well, the author’s voice is often mixed in with those of the interviewees, whose stories are presented through a diverse array of formats including first-person testimonials, question-and-answer format, poetry, and even a play. Sometimes it is unclear who was speaking. Despite these quibbles, this reader found some gems in this collection, which deals with an important subject.

In their own way, all three of these books add to our understanding of the social, political, and economic underpinnings of good health for all Canadians. They constitute an essential read for students of health care, nursing, medicine, social welfare policy, political history, Aboriginal history, and perhaps many other fields besides.

Page revised: 3 April 2020