by Gordon Goldsborough

University of Manitoba

|

I approached this book, written for the centenary of the Alpine Club of Canada’s founding in March 1906, with two questions: “What would prompt anyone to establish a mountaineering club in a flat place like Winnipeg?” and “What motivates people to climb mountains?” After reading it, I am not sure that I found satisfactory answers but I did learn about little known aspects of Manitoba’s past, and what today’s climbers are up to.

I approached this book, written for the centenary of the Alpine Club of Canada’s founding in March 1906, with two questions: “What would prompt anyone to establish a mountaineering club in a flat place like Winnipeg?” and “What motivates people to climb mountains?” After reading it, I am not sure that I found satisfactory answers but I did learn about little known aspects of Manitoba’s past, and what today’s climbers are up to.

The Alpine Club of Canada was founded by Arthur O. Wheeler, a surveyor with the Topographical Surveys Branch of the federal Department of the Interior, along with Winnipeg resident Elizabeth Parker, originally from Nova Scotia, who served as the first Club secretary. It seems the Club was intended to foster opportunities for people to enjoy the mountains of Alberta and British Columbia that had been made more easily accessible by the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. (The CPR played a major role in promoting awareness and interest in the mountains, employing Swiss guides to assist novice climbers at its mountain hotels.) The Club’s original constitution had a distinctly conservationist agenda; it was to be “a natural trust for the defence of our mountain solitudes against the intrusion of steam and electricity and the vandalisms of this luxurious, utilitarian age; for the keeping free from the grind of commerce, the wooded passes and valleys and alplands of the wilderness.” (8) Headquarters were in Winnipeg, staffed by Elizabeth Parker, her assistant Stanley H. Mitchell, and Jean Parker, her 22-year-old daughter who served as librarian. The office moved to a new clubhouse at Banff in 1909, near its present location in Canmore.

This volume is an anthology of articles, some of which were published elsewhere, others being original. They are organized chronologically into sections that loosely follow the wax and wane of the Club: “The Early Years (1906-1940)” describe the founding and early activities, largely in the Rockies; “Quiet Times (1941-1970)” concerns the life and death of prominent climbers like Elizabeth Parker and Alexander A. McCoubrey; “Rebirth and Growth (1971-1995)” addresses the resurgence of interest as new climbing areas in Manitoba were explored; and “Today and Beyond (1996-2006)” looks at present and future Club interests. The authors form a diverse group, from literary giants like Reverend Charles W. Gordon (Ralph Connor), who writes of his 1891 climb on Cascade Mountain in Banff National Park, to school teachers, students, lawyers, engineers, and others who are the modern Club members. As an aquatic scientist, I was surprised by the number of my peers who have played influential roles in Canadian mountaineering: Ferris Neave, who taught at the University of Manitoba in the 1920s and ’30s; renowned fisheries biologist William Ricker, whose son Karl wrote an excellent biography of Neave for this volume; Everett Fee, a research scientist and ardent rock climber now enjoying retirement near Banff; and former Winnipegger Robert France, who in his article about climbing Mount Manitoba in the Yukon, immodestly informs the reader—in two places—of his shared membership in the Order of the Buffalo Hunt with Mother Teresa and Pope John Paul II.

Perhaps due to the pioneering roles played by female climbers like Elizabeth Parker and Margaret Fleming (a Winnipeg teacher who spent summer holidays in the 1920s through ’40s in the mountains), it seems Club membership was not as exclusively male and WASPish as was the case for most “sporting” clubs of the early twentieth century. Women figure prominently in photographs throughout the book; Christine Mazur’s article “Fly on the wall” describes an exuberant climb by a group of women. An equally encouraging sign of diversity is Wayne Selby’s article describing le Club d’escalade de St-Boniface, the first francophone section of the Club. The Club’s attention was first focused on the western ranges, perhaps because they seemed massive and “wild” to those used to the comparatively “tame” mountains of eastern North America and Europe. It seems odd that appreciation for the excellent climbing opportunities afforded by the boulders and rock outcrops of the nearby Precambrian Shield were not realized by Manitoba climbers until the 1970s. More recently, climbing towers and walls erected in Winnipeg enable people to climb anywhere—even indoors!

This book is clearly intended for climbers first, and historians second. Several of its chapters contain jargon that is virtually incomprehensible to the uninitiated. A story about climbing in the Lake Louise area advises, for example, that “a 5.4 pitch in the Rockies is a chossy mess with less-than-spectacular protection.” (178) Some of the chapters are perhaps best described as quirky and the rationale for including them in this volume is unclear. Historians will also be frustrated by the fact that details about the Club’s past are sprinkled throughout the book, and there is no single chapter that provides a concise overview. (An article in the August-September 1994 issue of The Beaver might have helped.) Interesting photographs of climbing activities through the years are sprinkled liberally throughout, including at least two of climbers on their bums, displaying the wildly studded soles of their boots to the photographer.

I never found a clear answer to my first question, but I suspect it relates to the fact that, in the early twentieth century, Winnipeg was the sole prairie metropolis, where the wealthy and powerful members of the Club would naturally gravitate. On the question of what motivates people to climb mountains, I liked Hana Weingartl’s insight: “… I think it starts with learning to believe in yourself – trust yourself and your judgement and then you start to like the fact that you can actually do things and then for me it’s slowly moving to a spiritual part of life – especially with the big mountains. You realize there’s more to life – it’s kind of direct contact with it. There’s more to life than your physical existence. You feel pretty insignificant on a very big mountain.” (172)

When it was founded in 1906, the Club’s objectives were grandiose: “the promotion of scientific study and the exploration of Canadian alpine and glacial regions; the cultivation of Art in relation to mountain scenery; the education of Canadians to an appreciation of their mountain heritage; the encouragement of the mountain craft and the opening of new regions as a national playground; the preservation of the natural beauties of the mountain places and of the fauna and flora in their habitat; and the interchange of ideas with other alpine organizations.” (7) I had hoped the book would conclude with an analysis of the extent to which these objectives were achieved over the Club’s one hundred years but this anthology provides no such introspection. Instead, it ends with a salutary greeting from 16-year-old Afton McKee who shows that the Alpine Club of Canada is relevant to a new generation, something that at least bodes well for its existence for another century.

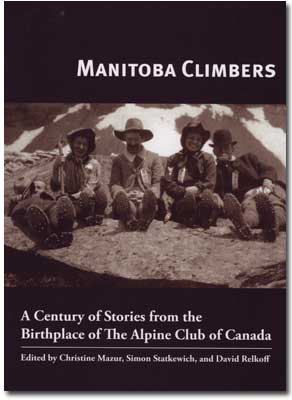

Members of the Dolomite Club climbing at Gunton Quarry, Manitoba, 1940s; top to bottom: Ferris Neave, Margaret Fleming, Marjorie Macleod.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Alpine Club of Canada MG10 D28, 1981-178.

Page revised: 29 June 2012