by Esme Keith

St. John’s Ravenscourt School, Winnipeg

|

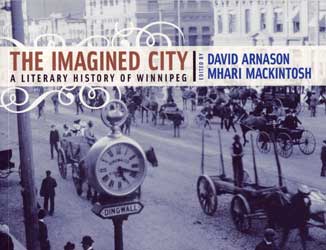

David Arnason and Mhari Mackintosh celebrate the city of Winnipeg in their collection The Imagined City, A Literary History of Winnipeg. They argue that “All great cities are known … by their representations in art” (ix), and they present their collection as an opportunity for readers to explore Winnipeg, as it appears in literature.

In this undertaking, the editors have set a challenge for themselves, searching for work that simultaneously represents Winnipeg and can also reasonably be described as “art.” They find lots of material that describes the city, but isn’t particularly notable as literature, and they include some good writing, as well as some work by established figures, in which Winnipeg makes a cameo appearance. However, on occasion they manage to uncover material with the double whammy of great writing and local resonance.

Carol Shields, Miriam Toews, Adele Wiseman, the city’s most celebrated writers are all represented, as they should be. The collection also contains some terrific, less familiar writers, chief among these Jack Ludwig. The selection from his story, “Requiem for Bibul,” bursts with energy and conviction.

However, some selections, like Margaret Laurence’s meditation on the nuclear arms race, don’t seem immediately relevant to the theme of this book. And other selections are so brief that they do not make the impact that a fuller quotation might. Ernest Thompson Seton, a writer whose stories reduced generations of children to puddles of woe, is represented only by a couple of pages from Animal Heroes. Removed from its larger narrative context, the selection loses much of the power available in Seton’s complete stories, although it does convey some sense of a rough and ready frontier life in Winnipeg.

Selections chosen primarily for their description of or allusion to the city, while informative, can make for dry reading. The very first piece, a selection from the fur trader and pioneer Alexander Ross, consists of two paragraphs describing houses and building materials in the Red River Colony.

Other nonfiction accounts, however, are more dynamic. William Francis Butler, the “advance scout (spy)” (p. 9) for Wolseley’s Red River Expedition, writes in the swaggering voice of a tough guy getting on with business. The brief account of his adventures makes lively reading. However, this selection also points to the most obvious failing of The Imagined City; that is, the collection’s circumscribed range. We hear Butler’s account of his work, but we hear no corresponding voice from his opponents. The Imagined City is under no obligation to present a series of arguments and rebuttals; and obviously, a hundred and fifty years of history can produce a staggering number of documents from which the editors must make their selection. But it is a definite loss that this book contains so little material by or about the French or Métis communities.

Sir William Francis Butler (1838-1910) wrote The Great Lone Land to describe his travels in the Canadian west in the early 1870s.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Personalities - William Francis Butler 1, N10492.

This absence is surprising given the editors’ evident concern to represent the many cultures of the city. As the editors point out in the Introduction, Winnipeg has a rich cultural mix, including French, Métis, First Nations, Scottish, English, Icelandic, and Eastern European populations. Several of the most gripping selections depict life intensely lived in one or the other of these communities. The North End, with its immigrants from Eastern Europe, is well represented in a number of different genres, including fiction by Jack Ludwig, memoir by Adele Wiseman, and poetry by Maara Haas. These are among the most involving of the selections.

Other material conveys the friction between cultures. Terms like “half breed” turn up regularly in the earliest pieces, reminding us of an age when racism was, if not more widespread, then more casually revealed. A chapter titled “City of Dreadful Night” includes several pieces addressing issues of violence, crime, and poverty, and, disturbingly, the majority of First Nations writers included in the collection turn up in this section. Given the absence of the Franco- Manitoban voice, it is a relief to find the First Nations represented. However, their segregation in a section dealing with civic misery raises its own troubling issues.

The dominant, enfranchised Anglo-Saxon community is also well represented. The different writers deal with a huge variety of topics, including social life in the Red River Colony, sports and entertainment, and the two world wars as they were experienced by citizens of Winnipeg.

But some themes recur frequently. One is an interest in asserting Winnipeg’s status within Canada or the British Empire, and maintaining its close connection with those larger entities. George Young, in his nineteenth century memoirs of Manitoba, quotes the first telegram sent from Winnipeg by a grateful Lieutenant Governor: “The first telegraphic message from the heart of the continent may appropriately convey on the part of our people an expression of devout thankfulness to Almighty God for the close of our isolation from the rest of the world” (18).

Other ongoing concerns are commerce and real estate. Stephen Leacock offers an economist’s perspective on supply and demand in Winnipeg, the comparative wealth of its citizens and the difficulty of transporting materials combining to create “the staggering prices paid for real estate while the place was still little more than a hamlet” (63). In The Magpie, by Douglas Durkin, the character Gilbert Nason is described in part by the house he lives in.

Douglas Durkin (1884-1967), author of The Magpie, fishing on the Grass River, no date.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, John A. Campbell Series IV, #17. N89.4.26.

Many of these selections tacitly insist that a city is, at heart, a physical entity. You know you are in a city, they indicate, if there are a lot of buildings and roads. A refinement of this view argues that a successful city has big buildings, and lots of them, and good roads, too. So Hugh MacLennan’s rather unconvincing, Hemingwayesque hero deplores Winnipeg’s failure to erect a skyscraper and so become one of the “cities of the world” (p. 137). And lots of people complain about the roads, though mud, rather than potholes, is the most common subject of complaint.

Another possibility is that a city is simply a place with a large, dense population, and in this regard, everyone can agree that Winnipeg measures up, although, especially in nineteenth century accounts, estimates of the city’s population seem to vary.

Aside from its cultural mix, one of the most striking aspects of the population of Winnipeg, as shown in these selections, is its transience. Pioneers pass through Winnipeg to buy supplies and move on to the homestead; churchmen visit Winnipeg as part of a tour through the territory; representatives of the Hudson’s Bay Company spend days in Winnipeg to work and socialize; journalists arrive in Winnipeg and file stories for their papers back east. People arrive: the Remittance Man from Britain, and the girl from the country. But people also leave again. Ludwig’s Bibul dreams of New York City, and many of the writers included in this volume stop in Winnipeg for a few months or years, and move on.

Before the Europeans, the First Nations used the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers as a meeting point and trading place, a place where people came together, did business, and departed. In many ways, from the evidence of these pieces, that is still a part of the city’s essential character.

Selections in The Imagined City are organized into roughly historical chapters: “The Early Red River,” “Boom Town Winnipeg,” and so on. In spite of the more or less chronological organization, an orderly, cover-to-cover reading of the book can be somewhat challenging because of the brevity of the entries, and the absence of editorial comment on individual selections. The editors provide a brief biography for each writer on his or her first appearance, and beyond that restrict themselves to a somewhat generalized Introduction. The volume is generously illustrated and includes an index and bibliography.

Page revised: 16 June 2012