by Brian Richardson

Ballinalacken, Lisdoonvarna, County Clare, Ireland

Number 46, Autumn/Winter 2003-2004

|

Friendship has many degrees. Ranging from acquaintance to deep kinship, it encompasses a huge swath of human emotional interchange but at core keeps one aspect, a bond of affection. Beyond that bond may lie anything from rivalry to close co-operation, self sacrifice to patronisation, patronage to hospitality, similarity and opposition, and so forth, ad infinitum. In the case of the friendship between George Simpson, Governor of The Hudson’s Bay Company in the mid-nineteenth century, and Andrew McDermot, free trader of the Red River colony, the spectrum covered included many of the above-mentioned qualities. The two men were close in age but of different countries and different aspirations. One might refer to Simpson as an Anglo-Scot, in which case McDermot would be seen as Old Irish, under the dominance of an English Empire.

Yet there are similarities in birth, at least as far as legalities go. McDermot family history mentions Andrew’s mother as the “natural wife” of Myles McDermot, Prince of Coolavin. Kitty (Catherine) O’Connor was the sister of Myles’ first wife who had died some time previously. The sisters were daughters of Charles O’Connor, a renowned Irish antiquarian who held the title of The O’Connor Don, which meant he was a direct descendant of Rory O’Connor the last High King of Ireland at the time of the Norman invasion in 1169. As Andrew always claimed to have been born at Bellengare House in County Roscommon that would mean he was born in the home of his maternal grandfather. The term “natural wife” would imply that the legal bonds of marriage had not been entered between Myles and Kitty and by law that would make Andrew illegitimate, or, more succinctly, a bastard. Not that this appears to have been a particularly great issue in either the McDermot or O’Connor households. There are two different years given for Andrew’s birth: 1789 and 1790; most commonly it is thought to be 1790. The newborn was baptized in the Catholic Church as Andrew Myles McDermot.

The birth of George Simpson in Lochbroom in the Scottish Highlands a few years previously, in either 1786 or 1787, was a far more opprobrious affair under the strict moral code of the Scottish middle class of the time as his mother bore him out of wedlock. However, it was his father’s family that took responsibility for him, and George was raised by his aunt, Mary Simpson. It is believed that he received an education in the parochial school as he grew toward early manhood, although that appears to be the extent of his formal schooling.

|

|

Andrew McDermot |

For a Catholic family in Ireland there was no formal education. Catholics had lost much of their rights in Ireland under the Anti-Popery Laws of the Eighteenth Century. In most cases only the old dominant families who converted to Protestantism kept their lands and position under the law. The Prince of Coolavin may have had a title but he had little in the way of estates to supply a living. Catholic families who had some financial resources often sent their sons to Europe to be educated. Andrew was not in such a fortunate position. His grandfather had died within a year of Andrew’s birth and his father died the following year; if Kitty continued to live at Bellengare there still would be little chance of her being able to afford sending Andrew abroad. Instead, like much of the Irish population, Andrew received his education in the hedge schools. These were schools conducted by scholars out of sight of the authorities, as education was prohibited to Catholics, and one’s learning depended upon the knowledge and abilities of the teacher. He must have had fairly decent tutelage, for he could write in English and was capable in mathematics. Of course, he also spoke Gaelic, which was the language of the people. He may even have had some grounding in the classical languages as many of the hedge schoolmasters had knowledge in that realm. Whatever degree of education he had it was enough to qualify Andrew as an Apprentice Writer with the Hudson’s Bay Company when he signed on in 1812 as a young man of twenty-two.

The route taken by George Simpson into the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company was rather more circuitous. He moved to London around 1800. His uncle Geddes McKenzie Simpson employed George at Graham and Simpson, the sugar brokerage firm in which Geddes was a partner. Through a merger in 1812 the partnership expanded to include Andrew Wedderburn. A shareholder in the Hudson’s Bay Company, Thomas Douglas, The Earl of Selkirk, was married to Wedderburn’s sister, Jean. Through that connection the Wedderburns became shareholders in the Hudson’s Bay Company and Andrew Wedderburn became a member of the governing board. It was with Andrew Wedderburn’s sponsorship that George Simpson was hired by the HBC. In 1820 Simpson was sent to observe matters in Rupertsland, where rivalry with the Montreal based North West Company had begun to seriously affect the trade of the HBC. This rivalry was not new, it had existed ever since the NWC had been formed in the latter part of the Eighteenth Century but had been increasing ever since 1810 when the HBC responded to the Montreal based company’s challenge to its monopoly. On his way west from Montreal Simpson met with the NWC partners at Fort William to inform them that Lord Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and The Colonies in the British Government, was calling for an end to the violence between the two companies. Wintering in the Athabasca, Simpson began directing his energies toward ways of bringing the ruinous rivalry to an end in his appointed capacity as Governor in Chief, and set out to examine as many aspects of the business as was possible. He also began instituting a change of tactics in HBC ranks, stopping bullying responses to the NWC and concentrating on economy and discipline. If experienced officers had suggestions he felt were viable they were appropriated and applied. Industry, not intimidation, was to be the way the company succeeded.

During the same years, Andrew McDermot had been demonstrating his business sense too. However, his abilities were apparent in the more direct employment of a Trader. Before he had even landed at York Factory on 26 August 1812 in his essentially clerical position of Apprentice Writer, Andrew had shown a quality of his character which may have had its root in the upbringing he had enjoyed as part of an old Gaelic chieftainship family. On board the Robert Taylor, upon which he had embarked in Sligo in the next county to his native Roscommon, McDermot had prevented a fight from breaking out between Irish settler labourers and the Scottish Shetland and Orkney employees. It appears he quickly learned the Scots Gaelic that was dominant on board. He had got to know many of the Scots settlers who had been sponsored by Lord Selkirk little knowing that someday he would himself settle among them as a merchant. Furthermore, the rations being fed the settlers were of low quality and scarcely of an amount to sustain them. When the settlers got up a petition demanding that the ship’s captain increase the rations they were desperate. In support of their cause McDermot signed the petition. It is possible that he even helped draught it, as it is unlikely that any of the Settlers could write in English. Whatever the case, it may be that as an officer, albeit a very junior one, his signature may have gone a way toward impressing the captain that a passenger mutiny could well erupt if the food question were not addressed. This sense of standing up for the disadvantaged could well have come from a background of clan responsibility. Shortly after his arrival in North America at York Factory for his first assignment Andrew was sent to Red River by York boat, doubtlessly arriving before the settlers who had to make much of their way on foot.

By the time Andrew McDermot was to meet George Simpson he had changed posts several times and had climbed in rank to Trader In Charge and had shown an aptitude for native languages. In this he may well have been aided by his young wife who had a Cree grandmother, a Saultaux mother, and an Orkney Scots grandfather. Young wife is a very apt description, for when Andrew took Sarah McNab as his country wife in 1814 she was but twelve years old. By the time she was fourteen she had given birth to Marie, their first child. This was the same year of the clash between settlers and Metis at Seven Oaks at which McDermot’s friend and countryman, John Bourke, disappeared. It appears to have also been a year when the effects of a volcanic eruption were having an impact on crops in various parts of the planet. It is likely that when Simpson was touring the company operations in 1821 that the two men met.

It was in March of 1821 that the rivalry between the London and Montreal based companies had come to an end. A merger of the two was agreed upon and the new company emerged as The Hudson’s Bay Company. Keeping the old company name meant holding onto the charter granted by Charles II, monarch of the kingdoms of the British Isles, in 1670, which essentially gave the HBC a trade monopoly of the area of the entire drainage of Hudson’s Bay. Although the King’s geographic knowledge of the area was as limited as that of the company partners, he had unknowingly given them control of the entire northern Great Plains and vast stretches of the Canadian Shield. (Unbeknownst to the native population who inhabited the territory and who had no concept of the claim or its subsequent implications.) The newly merged company could now claim the monopoly without interference. Simpson was faced with the task of integrating the operations of the former rival companies, eliminating redundant posts where the companies had both operated, and reducing excess staff numbers. This meant that he had a larger workforce from which to choose the most efficient officers, workers, and transporters. Naturally, this meant inspecting as much of the operations of the merged companies as he could. He used a “Character Book” as a way of noting the abilities of the staff. His entry for Andrew McDermot was recorded in 1822, which makes it likely that he visited Thieving River where Andrew was posted in 1821 and his term ran from September to the following August when he moved to Netley Creek, much closer to Fort Garry. “ Sober, steady and honest. Deficient in education but a good trader. Has intimated his intention of retiring next season to Red River.”‘ That was how George Simpson assessed Andrew McDermot.

Simpson had a swift canoe, crewed by voyageurs who prided themselves on their speed and distance, and he enjoyed arriving unexpectedly at company posts in order to find the officers and men at their routine, unadjusted by news that the man to whom they were responsible was due to visit. No doubt his unexpected arrival did not overly concern McDermot. It is likely that the Governor would have dined at the Officers” Mess with Andrew and his assistants. It may even have been that he enjoyed McDermot’s hospitality, for McDermot carried a tradition of family pride in hospitality, a characteristic of honour among the old Irish clan chieftains which was to manifest itself over the years.

It is a curious note that Simpson takes in describing McDermot as “sober” in his character book of 1821-22, for apparently Governor Simpson was not. It well may be that the Governor enjoyed drinking with the trader during, and after, dinner and the conversation when the Governor was in his cups may have given his more sober host information he would not normally hear.

For a time, like the Norwesters, HBC men were encouraged to form liaisons, or “country” marriages, with mixed blood or native women as a way of connecting to those who trapped the furs that were the core of the company’s trade. As McDermot was apparently quite fluent in some of the native languages [2]—probably Cree and Ojibwa—he may have attributed some of his knowledge of these tongues to Sarah, his wife. Certainly Simpson recognized the usefulness of the women of the country, as contacts with the native community and as sexual partners, but he appears to have seen them purely in a utilitarian sense. [3] (Simpson is known to have referred to his own country wives as “bits of copper”.) It is likely that he saw McDermot’s country marriage in this light. Nevertheless, this first meeting was to lead to further contact developing between the two men.

Since McDermot had intimated to Simpson his intention of leaving the company the following year, and because Andrew reportedly stated that he saw little opportunity for promotion within the HBC, he clearly saw other possibilities in independence. The shrewd businessman in Simpson no doubt filed this information away, for he was to avail of these circumstances some years later.

As he later claimed, in spite of Simpson making him an offer with some sort of promotion if he would renew his contract, he had determined to retire from company service and find his own way. [4] When McDermot left the company service, not renewing his contract in 1824, the family moved to Red River, the area close to The Forks where the Assiniboine and Red Rivers conjoin. This was the locale where the Selkirk settlers, with whom he had crossed the Atlantic, had made their farms and where many of the retired officers went in the wake of the merger. As Alexander Ross, the chronicler of the settlement’s early years, wrote

Mac did not hesitate to spend on an outfit of horses, carts, and employees, to try his fortune on the plains. He went on his first jaunt to learn buffalo hunting actively and commercially, in the year of his arrival at Red River. Having secured his interest among the hunters, he branched into other lines. Not only was he doubling his money on every buffalo hunting trip, but he set up a shop in Red River and became an extensive importer from England and the United States. [5]

The Hudson’s Bay Company post at York Factory at the time of Andrew McDermot’s arrival in August of 1812.

Painted by Peter Rindesbacher. Source: National Archives of Canada

As the last year of his contract was spent at Pembina, by the U.S. border, where the Buffalo Hunt was centered, it may well have been an easy decision. McDermot was acknowledged a fine horseman and appears to have had a good companion on the hunt in Jock Wilkie. In fact, his experience with the hunt and his eye for horseflesh stood him in good stead. If one is to ride on the buffalo hunt one needs to know how to ride well and apparently Andrew did. This skill may have been learned on the plains of Roscommon in his youth, for the Irish have a long-standing passion for horsemanship. Even to this day many towns and villages in Ireland stage local horse races.

The newly constructed Fort Garry on the west side of the Assiniboine close to The Forks was a walk through dense wood, through which the buffalo came down to drink out of the Red River from the plains just beyond, as Sarah was later to describe. [6] Here Andrew set up a store and began to construct the home which was to be known as Emerald Grove. That same year daughter Jane was born.

To judge by the comments of his friend and neighbour, Alexander Ross, McDermot did not take long to become a successful businessman in the growing colony:

By his address and accommodating qualities, aided a little by no lack of Irish wit, he soon drew public attention to his business. He was everybody’s man, and formed the centre of attraction: for he could lend a horse, change an ox, or barter a dog, as circumstances required. If a stranger, of whatever rank, chanced to visit the place, although he kept neither inn nor hotel, yet accommodations for both man and beast were always ready. A house to let, a room to hire, and every want supplied. If a contract was contemplated, or an enterprise proposed, or if money was wanted, who but McDermot was the man to do the good turn? Such being his character and services, ten years had not elapsed before he overstepped all his competitors in the settlement, as he had done in the plains. Uniting the resources of the plains with his affairs in the settlement, he stands at the head of both, in point of popularity and enterprise. It is a common saying here “that the bush he passes must be bare and barren indeed, if he does not pluck a leaf off it. His discriminating knowledge of men is proverbial; nor is it confined to men alone; as a judge of horses, he stands unrivaled. [7]

American traders were moving into the Pembina area. The HBC saw this as a threat to their trade in the region. While the company itself could not legally trade in U.S. territory, an independent trader could. McDermot as an independent merchant was already dealing in pemmican and was on good terms with the settlers. If the company had some way of dealing with the needs of the settlers without tying up their own traders, whose primary occupation was the fur trade, it would be advantageous to have somebody outside the company carry on that trade. Of course, because of the HBC monopoly McDermot was not permitted to deal in furs. However, Simpson saw an advantage that could deal with the settlers and certainly solve the problem of the American traders’ incursion just below the border. With McDermot’s contacts in Pembina from his final company posting he was the ideal person to license to trade in furs, especially as the HBC would pay for whatever he traded there. The HBC would import the trade goods McDermot needed in the annual supply ship from London to York Factory, and Simpson would have a man he trusted opposing the new trade threat. Andrew was in business in furs, thanks to a curious blend of opportunism and trust.

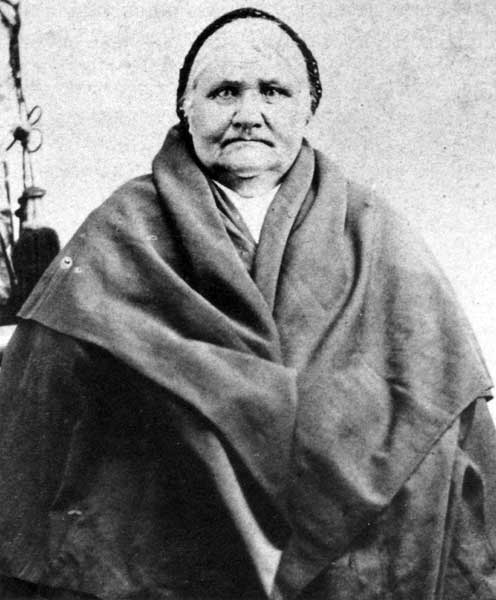

Andrew McDermot’s wife Sarah McNabb, no date.

Source: Thomas Sinclair Collection

It can well be imagined that some of the less formal discussions about this new arrangement took place at Emerald Lodge and possibly at the Governor’s quarters at Fort Garry. Simpson was now Governor of the Northern Department of company activities and was applying his vigour and business sense to the development of the profitability of his charge. Mac, as both Simpson and Alexander Ross called Andrew, was as hospitable as ever and had a generous hand while pouring drinks for his guests. (There is a delicious irony that two Scotsmen would call their fish friend by that most Scottish appellation of “Mac”; an irony probably not lost on either of them.) One can only speculate on the content of the conversations between McDermot and Simpson but circumstances of birth and social position must have entered into their exchanges. The fact of McDermot’s noble Gaelic lineage would not have been lost on Simpson, a man who clearly had aspirations of class distinction. After all, his friend and sponsor, Andrew Wedderbum, who had since changed his last name to Colvile, was the brother-in-law of an Earl. On the other hand, the Irish were very much reduced in the eyes of the British. It would appear that Simpson was the type of Scot who sought acceptance in English terms. Even his note about McDermot’s education in his character book betrays a certain patronizing attitude. Behind this attitude there may have been a certain rivalry, for McDermot was of an old established family, even if it was in reduced circumstances, and Simpson was not, even though the Simpson family was quite respectable.

The arrangement worked satisfactorily. McDermot’s trade prospered south of the border and as the years passed his business interests increased in scope. He included freighting by operating a fleet of Yorkboats under his supervision and there are several references to him traveling in them up to Norway House and other destinations. [8]

He has been described in those times as “a most energetic man, always busy, always on the move, constantly to be seen going about the numerous buildings which he gradually erected about his home, always singing snatches of Irish songs. He was very fair, wearing his light hair rather long.” [9] Emerald House was added to at various times and has been described as a rambling building with a remarkable wine cellar, which was quite surprising for a man with as abstemious reputation as McDermot had. In those days the chimneys were made of mud, a not uncommon material of construction in the settlement at the time. However, it was comfortable, and, as there was no hotel in the colony, visitors often enjoyed the hospitality of the McDermots and their ever-expanding family in their ever-expanding house. Whenever Simpson was resident at Fort Garry he would have had reason to be in contact with McDermot, certainly for business reasons but perhaps also to enjoy McDermot’s hospitality and his wine cellar. Simpson was very much a man of his time when it came to the consumption of alcohol, as it was viewed as manly to be able to consume large amounts and Simpson was always challenging himself and his constitution.

With Fort Garry as the plains headquarters of the trade Governor Simpson had based himself in the region. Although he had a disparaging view of native and mixed- blood women, he had not withheld himself from the pleasures of liaisons with them. He even had some children from these convenient couplings, but for a man with ambitions rooted in the gentile respectability of the Great Britain of the nineteenth century such “going native” was not sufficient. So, Simpson determined to find himself a respectable “white” wife back in the home country. The one whom he chose was his eighteen year old cousin, Frances, daughter of Geddes McKenzie Simpson, the uncle who had given him his start in business. They married in 1829 and arrangements were made to sail back to Montreal. Of course, George had no desire to confront Frances with his dalliances at Red River, so he settled his country wives and their children with various company members, made sure they were provided for, and ensured that no country wives of any officers or friends were admitted into his British wife’s company. He also decided to move his headquarters downriver, north of the St. Andrew’s rapids. The new location was to be called Lower Fort Garry and constructed of stone. Work commenced on it in 1831 with stonemason Duncan McCrea, some of whose descendents still live in the area.

Andrew McDermot’s store in the Red River Settlement. Photographed in September 1858.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

After their canoe journey from Montreal, the Simpsons were established at Red River. Residing with the family was George’s cousin, Thomas Simpson, who was employed as his confidential secretary. However, there may have been a certain amount of mistrust between the cousins, as Thomas was not given access to George’s private papers—not much confidentiality there. Perhaps, because George was an illegitimate member of the family Thomas may have carried certain attitudes, which, even if he took care not to be obvious, may have been evident to one as aware of his position as the Governor was. The minor imperialism of Simpson evidenced itself in his transportation. The carriage made by Le Blanc, who was working on the stone fort, and outfitted for the Governor with a coat of arms emblazoned on the side, certainly betrays some ostentation. The governor would ride in tandem with his wife in the narrow conveyance, often at a very fast pace. [10]

In spite of the friendship between McDermot and himself, Simpson did not invite Sarah McDermot into the social circle he created about Frances. While Frances may have agreed in principle with the purely white nature of her company, she apparently found most of them boring, particularly the wife of William Cockran, the opinionated, energetic Anglican missionary. She preferred the company of Mary Jones, wife of the Reverend D. T. Jones. The Joneses gave grand parties rival only to those given by the Governor. [11] In early 1831 Frances was being attended by Dr. Todd, as she was ill with her first pregnancy. [12] It appears to have been a pregnancy that required much rest and medical attention. She delivered George Junior on 2 September 1831.

Simpson had bought two or three horses, one in particular purchased by a fellow named McMillan at Pembina, in which he took pride. (This was likely James McMillan who had accompanied Simpson on a rapid canoe journey to the West coast in 1824.) The birth of a son, particularly a legitimate one, made the Governor feel in his prime. Only twelve days after the birth (14 September) he raced his Pembina horse against Tommy, McDermot’s champion, and, on this occasion, won. [13] It is not difficult to picture his boasting rights being employed to the maximum after the victory. It may have been a spur to McDermot too. The license to trade in furs granted to McDermot by Simpson appears to have been well in place at this time and some of the rivalry may have been exacerbated by the fact that the McDermots were doing rather well. Unfortunately for the Governor, the swagger was reduced the following 24 April when, returning from Easter Sacrament at Middle Church, Frances’ firstborn died almost at the moment of Frances’ arrival home. [14]

The exclusion of Sarah McDermot from the society of Mrs. Simpson must have meant that McDermot too was not a family guest of the Simpsons. In fact, following the Governor’s example some of the new officers joining the company sought wives in the “old country” and the practice of marrying the “countryborn” was discouraged. One can almost hear Simpson saying to McDermot, “ It is time to exchange the copper for some silver.” Considering the durability of Andrew’s and Sarah’s union, this attitude of Simpson must have been an annoyance to McDermot. However, his license to trade in furs was dependent upon the Governor’s good will and McDermot may have kept his own counsel on this matter. Like Simpson he was able to separate his business from his private life. Even the rivalry in the horse race reveals Simpson’s need to show his superiority to McDermot and again as a reflection of his manliness in defeating the local champion horse and rider.

A new problem facing Simpson arose in 1835 as, unbeknownst to many of the colonists, Lord Selkirk’s estate sold the settlement to the Hudson’s Bay Company that year. With the retired officers and families gravitating to Red River and the construction of a new and larger Fort Garry the settlement had grown. By this point had established his permanent headquarters at Lachine, Quebec, and Frances was now living in London to regain her strength after her disastrous years at Red River It became clear that some sort of civic administration was necessary. Rather than having to add such administration directly to his duties the Governor created the Council of Assiniboia for that purpose. Among the claims of the first settlers McDermot managed to acquire more land. Besides his land holdings McDermot’s position in the community obviously was one of prominence and he was invited to join the council along with the Bishop of Juliopolis, Chief Trader Donald Ross, Sheriff Alexander Ross (McDermot’s neighbour and friend), and Dr. John Bunn (Sarah’s cousin). Of course, Simpson’s trust played a factor in his invitation too. On 12 February 1835 the council met and Andrew McDermot was appointed to the Committee for Management of Public Works with Robert Logan and Alexander Ross.

Reportedly, Simpson said to McDermot, “You were made for the fur trade, Mac. You can walk snowdrifts like a wolverine, you can run like antelope, and you can stand the cold like a husky dog. Stay with us, and we will put you on the committee and keep you on it, and do well for you in the matter of pay.” [15] No doubt Simpson felt he needed McDermot’s loyalty and the appointment can be viewed as an unstated bribe. His own private business interests were expanding in Lachine and he needed responsible men rooted in the colony to see to its governance without the necessity of his presence. This would also leave him free to pursue his principal function, that of running the business of the company efficiently; civil governance was an unfortunate offshoot of the colony.

Alexander Ross, Red River’s first historian, no date.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

For Simpson family life resumed more normalcy when Frances came from England to join him. Over the years they produced four children, a son and three daughters. In 1839 he was appointed formally in the job he had already been doing for some years. Well integrated into Montreal society and the Anglo-Scottish business community, Simpson got involved in banking and railroad development, as well as mining, all expanding ventures in the increasingly industrial age of Queen Victoria’s reign. He managed to give sumptuous banquets with business and political figures in attendance and those contacts were put to use in service to the HBC. Nor did he stop traveling. How much time for family life he managed is moot. He was certainly a good provider if not a particularly nurturing husband and father.

After twenty-two years as man and wife Andrew and Sarah finally got married in the Anglican church, a far cry from Simpson’s way of dealing with country marriage. Apparently the minister presiding was William Cockran who never succeeded in persuading McDermot to join the Anglican Church. It is a comment on McDermot’s feelings about the proselytizing prelate that he only became a member of the Anglican flock the year after Cockran died. The McDermot family continued to grow and so did Emerald Lodge. When his daughter Helen (Ellen) married Thomas Bird a house was constructed for them in Emerald Grove on the grounds close to where Thomas ran McDermot’s grist mill. (The current Mill Street in Winnipeg takes it name form that mill.) Family life was close and comfortable The neighbourhood in which Emerald Grove was situated seems to have been conducive to raising a family. Alexander Ross and his family was close by at Colony Gardens. James Sinclair’s family was next to the Rosses. The Logans were just a bit further along to the north on the bank of the Red River. The families grew up together and the children knew each other well, visiting back and forth. [16] Harriet Sinclair remembers visiting the McDermot household with a maidservant one evening in the Eighteen Forties to see a magician. The price of admission was one buffalo sinew, a commodity which could be peeled for use as a strong thread. Having duly paid the fee Harriet saw the buffalo hunter, Desjarlais, put a watch under a hat and then lift the hat to show the watch had become a potato. He pulled reams of ribbons from the hat and did all sorts of awesome illusions. It may well have been the first vaudeville performance at Red River and it took place in the McDermots’ kitchen. McDermot had the touch of an impresario as well as a merchant. [17]

So during these years both Simpson and McDermot succeeded in their enterprises, albeit on different scales, each according to his nature. The societies in which each lived were evolving. Industrialisation in the east and the growing development of the Canadas was well underway. The isolation from other “white society” was diminishing for Red River as the Americans pushed further north up the Mississippi and the city of St. Paul became a terminus for steam driven riverboats. Slowly a Red River Cart trail developed through the efforts of men like James Sinclair and Peter Garrioch, which allowed for export and import beyond the HBC jurisdiction. Connecting to St. Paul the independent traders grew financially and influentially. This did not go unnoticed by the inhabitants of the settlement and with the arrival of American traders at Pembina the independent (or underground) trade increased, particularly in furs. The company noticed this activity and began to seek ways to suppress this challenge to its monopoly.

“McDermot’s from Bannatyne’s house”, painted in 1857. In the background is Upper Fort Garry at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

Even though James Sinclair was contracted by the HBC to freight goods in 1842, it was only a few years later that he and McDermot were being viewed by Chief Factor Alexander Christie as ringleaders of the movement toward free trade. Christie was also Governor of the Colony and had been so previous to his absence from Fort Garry for several years. He now decided to try and stop the insidious (as he saw it) whittling of the company’s monopoly. In his letters to Simpson he refers to free trade as an “evil” and similar depraved behaviour. [18] In a proclamation on 7 December 1844, Chief Factor Christie states that company ships would not receive, at any port, goods addressed to anyone unless that person lodged at the company’s office at Upper Fort Garry a declaration to the effect he had neither directly or indirectly trafficked in furs. In essence he had managed to withdraw permission for McDermot to send and receive goods via the annual company ship. In fact, Chief Factor Duncan Finlayson (who was married to the sister of Frances Simpson) cancelled the shipping contracts of McDermot and Sinclair in 1845. Letters between the two traders and Christie reveal a growing disgruntlement, while still remaining civil. In fact, Christie protests in a letter, in response to an accusation by McDermot, that he bears him no personal animosity and regards them still to be friends. At the same time Christie’s communication with Simpson villainises the two men. There was plenty of bluster in these mails and one can imagine some of the personal interaction, particularly as Christie would write a letter to McDermot after a meeting in the street. It is from the correspondence [19] that one can sense how McDermot would walk a fine line between what his license permitted and what he did. This was a particularly Irish characteristic of those (and later) times when English law did not sit well with the population. Rationalisation over skirting the law had become a fine art with the Irish, its best known proponent was a sixteenth century courtier at Queen Elizabeth’s court, Lord Blarney, who could make a profound speech at the end of which nobody would really know what he had said; leading Good Queen Bess to comment at one point on the circumlocution of a courtier to the effect of “Enough of your Blarney, my Lord!”

Simpson was, of course, aware of the actions taken by Christie and Finlayson, but when approached by McDermot concerning the latter’s license to trade he managed to diplomatically imply that his hands were tied as Christie had convinced the Committee in London to allow him take the actions he had and the Governor could hardly counteract without compromising his position in the company.

American traders like Norman Kittson were encroaching on the company’s range and there was a suspicion that Sinclair and McDermot were trading furs to the Americans around Pembina. Sinclair raised a petition in protest in a series of points claiming that the inhabitants rights as citizens were being ignored by the company. Christie countered by stating that they had the same rights as citizens in Great Britain and Scotland and so to look for nothing extra in the settlement.

When Christie accused McDermot of holding an “unlawful meeting” at his house McDermot disagreed. It was simply a meeting in which Abbe Georges Belcourt, had brought forward the notion of a petition to Parliament in London requesting an examination of the HBC’s right to govern and suggesting that as citizens the inhabitants of Rupert’s Land might enjoy the same rights as other citizens. Belcourt claimed that citizens of a democracy are allowed to petition government concerning their rights. McDermot claimed that at no point did the petitioners say they wished to usurp the government, while Christie argued that because the HBC was given control over the territory by Royal Charter any meeting which opposed company rule would therefore be treason against British government. In disgust with this view McDermot offered his resignation to the Council of Assiniboia.

As Christie grew more adamant about stamping out this “illegal” trade he pointed out to Simpson that even the local magistrates were unwilling to prosecute “illicit” traders for fear of disturbing the equilibrium of the settlement. [20] He had stated before that it would be better to have an independent force to help police the trade. “It might be necessary to introduce into the Settlement a body of disciplined troops for the purpose of giving still greater effect to our authority.” [21] So, when Christie learned in a letter from Simpson that the 6th Regiment of Foot was to be dispatched to the colony in the summer of 1846 [22] he was delighted, particularly as he appeared to think there was rebellion brewing.

Annie McDermot, the daughter of Andrew McDermot and wife Sarah McNabb.

Source: Thomas Sinclair collection

The troops were not simply dispatched to police the trade. Tensions with the United States had been growing over the Oregon territory and because of the company’s interests and posts in that region, Simpson had been involved in that sphere. There was a concern that rising Métis nationalism, which was tied into the free trade movement, might look to the Americans for support. So, there were several factors for sending troops to Red River. Whatever the cause, the soldiers were now stationed in the settlement. In spite of no longer having shipping rights on company ships McDermot still managed to conduct a profitable business. It helped that the Anglo-Irish commander of the troops, Major Crofton had recommended that they patronize McDermot’s store. Christie was appalled that McDermot was profiting so much from the very troops the Chief Factor had hoped would suppress McDermot’s business. So considerable was the profit that year that McDermot sent £2,000 to the friend who scrupulously handled his investments, George Simpson. [23]

The point was not lost on Simpson. The Governor had hoped that the newly promoted Lt. Colonel Crofton, who was viewed as a good administrator and one impartial to HBC influence, could be appointed as Governor of the colony. However, Crofton did not enjoy his assignment and on 16 June 1847 he handed over command to Major Thomas Griffiths and set out for Montreal and England. Simpson did not see Griffiths as suitable for the task of the governorship. Besides, the boundary dispute in the Oregon territory which had been a persuasive factor in convincing the Colonial Secretary to send the troops to Red River, had now been settled. It was clear the seasoned soldiers could better be used in other parts of the Empire and would soon be withdrawn. Despite the fact that the “illicit trade” seems to have been reduced with the presence of the military, on the other hand, the economy of the colony had expanded with the troops. In fact, Alexander Ross estimated that “during their short stay, the circulation of money was increased by no less than Fifteen Thousand Pounds Sterling; no wonder they left the colony deeply regretted.” [24]

McDermot may have made his money from the soldiers, but he also did get some recompense for his losses during the dispute on his license to trade. An understanding was entered into which he not only received some payment, but he was once more allowed to use company ships to import and export. He was also persuaded to rejoin the Council of Assiniboia and was duly sworn in on 15 January 1847.

The entire Free Trade issue came to a head two years later. This time McDermot remained behind the scenes. Some felt he did so because of the return of his shipping rights and his rejoining the council. As a member of council he may have felt it advisable to not be directly involved. No doubt he discussed the situation with James Sinclair, who had recently returned to the colony after delivering Belcourt’s petition in England for perusal by the parliamentary minister responsible. The climax of the situation arose when Adam Thom, Recorder of Rupertsland, senior magistrate position, prosecuted Guillaume Sayer and three companions for trading furs outside the company’s bailiwick. The trial raised the ire of the Métis and under the leadership of Louis Riel Senior about four hundred armed men marched on the courthouse where the trial was taking place. After much wrangling Sinclair was allowed to represent Sayer. While the Métis surrounded the courthouse the trial proceeded. Although there were troops stationed at Fort Garry they were Chelsea pensioners and had already proved troublesome to the colony. Besides, their commanding officer, Major Caldwell, was on the bench of the court that day and was not in a position to summon them. Although the defendants were found guilty, which satisfied Chief Factor Ballenden that the principle of the HBC monopoly was maintained, the jury recommended mercy as Sayer and the others had acted in the custom of the country. This was taken as a sign by Riel that the trade was now free. Perhaps under the company charter it was not, but in reality it was.

In the years that followed, the Red River settlement went through a further series of developments. Life in the McDermot household had changed as well. Having given birth at least sixteen times—not all of whom survived—Sarah was no longer bearing children. McDermot had been appointed a magistrate, although he rarely sat on the bench. In 1851, citing the demands of his business affairs, McDermot resigned from the Council of Assiniboia and as a Magistrate. Although, another factor had changed family life. The death of their eldest child, Marie, in Oregon meant that their father, Richard Lane, was now left with the task of raising young children alone. It was decided to send them across the Rockies to the McDermots where they would be better cared for in the home of their grandparents. Although in his sixties, and Harriet still a youngster, McDermot was still responsible for young children. There were other reasons for McDermot stepping down from local governance. The current colony Governor, Major Caldwell, had managed to alienate most of the council by his manner. His removal had already been petitioned of the Rupertsland governor, and the exasperation of all with him had certainly reached a high degree. After the Sayer trial Simpson, who was now Sir George, having been knighted for his services to exploration, was eager to be rid of direct involvement in Red River and had Eden Colvile (son of Andrew) appointed Governor of Rupertsland. Personal contact with Simpson would have by now become virtually non-existent for McDermot. Nor was he so reliant on company ships anymore as the route to St. Paul could bring goods more rapidly than the annual ship. With his business now diverse enough to be run by his children and their spouses McDermot’s business, as well as social contact, with Simpson had little urgency. Time and distance had diverged their paths.

One story which illuminates their friendship however was reported by the U.S consul, James Wickes Taylor. Although there is no date given for a prank he played on McDermot, it is likely that the Eighteen Fifties were the years when he sent three young men to “Old McDermot” bearing a bottle of brandy by way of introduction. As was his wont, McDermot entertained the gentlemen but soon twigged to the fact that something was afoot, particularly in the way they set about consuming alcohol and inviting their host to keep up with them. He poured liberally into their glasses, but did not dispense such generous portions to himself. Nonetheless, by the time the last of the guests had slipped beneath the table in slumberous state, McDermot was still clear minded. However, in his telling the story to Dr. Cowan and Consul Taylor, when they asked if the liquor had affected him, he replied, “Oh no, I was all right, but when I got up there was something wrong with my feet. I could not get them straight. But I was not drunk. Oh no, I was quite sober. You see, I knew they were trying to make me drunk.” It came out later that Simpson had wanted them to get McDermot drunk and get some information out of him, perhaps the way McDermot had when Simpson had been his guest years before. Simpson would have loved to have got one up on his old chum and rival in that way, but McDermot hadn’t lost his keen eye for finding out what others were hiding.

Simpson died of apoplexy in 1860 nine days after having entertained the Prince of Wales on his estate. To hobnob with royalty would certainly have been an apex of his career in Simpson’s eyes and so he departed this life having achieved this goal. Frances had predeceased him by several years.

Sarah predeceased her husband. When McDermot died six years later in 1881 he could look back at a life in which he had arrived to see the prairie being broken for farms in the midst of a wildemesss, and left it as part of Canada railways and steamships connecting it to the wider world, the fur trade which had brought him no longer a major part of the life of the colony, and the buffalo which had fueled the trade brought to the verge of extinction. He had lived a full life.

The descendents of both Simpson and McDermot continue to live in Manitoba. Both lines, interestingly enough, of mixed blood lineage, for it appears that Simpson’s Manitoba descendents are from his country wives. It is curious that one man had circumnavigated the world and the other had settled in one piece of country never to leave again, and yet their friendship had endured in its own course for many years. Each in their own way became leading citizens in the places where they established their homes; Simpson in the older city, McDermot in what was to become a city of which he was a cornerstone, his name attached to this day to an avenue at the center of the city where the northern boundary of his property once lay.

Upper Fort Garry

Source: Archives of Manitoba

1 . Hudson’s Bay Company Archives (hereafter HBCA), Archives of Manitoba, B. 229/f/12, George Simpson. Character Book 1821-22.

2. John S. Galbraith, “George Simpson,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

4. “Andrew McDermot,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. XI, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press) pp. 545-54.

5. Alexander Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress and Present State (London, Smith and Elder and Co., 1856).

8. Robert Logan file, January 1830 - December 1831. Box 442. HBC Archives. “ June 19 1831: McDermot with boats Passed Norway House bound for York Factory / Sept. 23 1831: Passed Norway House with boats bound for Red River.”

9. Gail Morin. English Ancestors of Andrew McDermot. http://www.televar.com/gmorin/mcdermot.html

10. Manitoba Legislative Library, M9, Winnipeg Free Press, 15 March 1930. Thomas Simpson to Donald Ross, 12 March 1831.

13. Manitoba Legislative Library, M9. Winnipeg Free Press, 15 March 1930, Thomas Simpson. Letter to Donald Ross, 15 September 1831.

14. Manitoba Legislative Library, M9 Winnipeg Free Press, 15 March 1930, Thomas Simpson to Donald Ross, 1832.

15. Alexander Ross, The Red River Settlement.

16. Mrs. William Cowan (Harriet Sinclair) in W. J. Healy, Women of Red River, Peguis Publishers Ltd.

17. Mrs. William Cowan (Harriet Sinclair) in W. J. Healy, Women of Red River, Peguis Publishers Ltd.

18. Alexander Christie to George Simpson, Red River Settlement Papers, Archives of Manitoba, MG 2 B5-2.

19. Alexander Christie to George Simpson, 21 April 1846. Red River Settlement Papers, Archives of Manitoba, MG 2 B5-2.

20. Alexander Christie to George Simpson, 31 December 1845.Red River Settlement Papers, Archives of Manitoba, MG 2 B5-2.

22. George Simpson to Chief Factors and Traders, 15 July 1846. Published in Winnipeg Free Press, 26 April 1930.

23. Dictionary of Canadian Biography Vol. X.

24. Dictionary Of Canadian Biography see John Crofton.

Page revised: 19 September 2010