MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1958-59 season

|

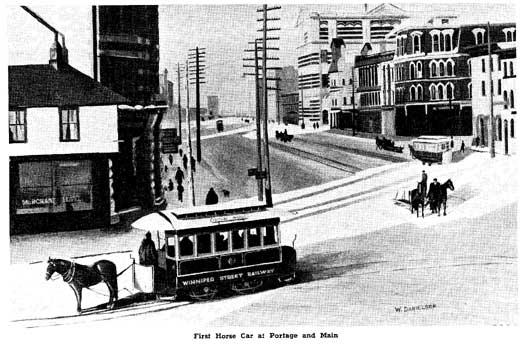

First horse car at Portage and Main

Transportation in the early days of Winnipeg was a tedious, time-consuming process. The city spread outwards like a fan from the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. These waterways were its early avenues of transportation, bearing, first - frail birch bark canoes: then the sturdy York boats, the barges, flatboats and river steamers.

On land it was wearisome travelling. Indian and animal trails that roughly paralleled the windings of the rivers became Main Street and Portage Avenue. About the middle of the Century - 1840-1850 - foot travel gave way to the ox-cart. More familiarly known as the Red River Cart, the primitive, two-wheeled vehicle, held together by rawhide and pegs, was a boon to the early travellers. It carried almost half-a-ton of freight over almost any kind of terrain. Crude and undeviatingly slow, yes, but a practical and progressive step in the early story of Winnipeg’s transportation.

The Red River cart was followed, briefly, by the stage-coach, but on 10 March 1878, Mr. Ira M. Carpenter, of the Blakely & Carpenter Minnesota Stage Co., arrived in Winnipeg to start closing out the stagecoach era. This mode of travel had seen only seven years of life, bridging the gap between the Red River cart and the coming of the railroad. The first stage had arrived in Winnipeg on 11 September 1871. The first train from St. Paul, via Emerson, steamed into the Station on 7 December 1878. Mr. Carpenter realized months in advance that the stage would be obsolete with the arrival of the “iron horse.”

Winnipeg, incorporated as a city on 8 November 1873, with a population of 1,869 became a key factor in the line of communications opening up the West. Yet, only a short time after incorporation, it took all the determination and fighting spirit of Mayor F. E. Cornish and a special committee composed of Messrs. McMicken, Bathgate, Ashdown, Belch, Luxton and Bannatyne, to save the city from relegation to the status of a wayside town. Their resolute efforts and tax concessions resulted in the C.P.R. bringing its main line from east to west through Winnipeg, thus ensuring the City’s future status.

It was inevitable then that Winnipeg would mushroom out into a thriving centre and would require extensive transportation facilities for itself and its suburbs.

The layout of Winnipeg could hardly be said to have been planned. Rather, it just straggled into place along the old trails. When the pioneers did attempt to shape it into an organized area they tried to arrange the streets like spokes from a wheel-hub and only partly succeeded. It created problems that still live with us today.

The first attempt to provide public transportation was premature and a failure. It was a one-day attempt made on 19 July 1877. A horse drawn omnibus operated between the Old Customs Building at Main and McDermot and Point Douglas, where the C.P.R. Station now stands. The editorial epitaph read, “It was ahead of its time.”

But, four years later, Winnipeg started taking a new look at transportation. People were pouring into the new City. A Mr. Albert W. Austin was focussing attention on the need for public transit. He organized and incorporated a Company known as the Winnipeg Street Railway Company. When the stock books were opened on 28 April 1881, they were subscribed within an hour. Prominent citizens were the leading backers, such men as A. Calder, J. H. Ashdown, David Young, Hugh Sutherland, and many others.

Albert Austin was a son of James Austin, founder of the Dominion Bank. Young Albert had expansive dreams. Two things above all, he wanted to do.

First: He wanted to move the city to the shores of Lake Winnipeg, where the water was clean and fresh; not like the disease laden water of the Red and Assiniboine, which was delivered in tank carts to the people.

Second: He wanted to run street cars along Main Street.

His youthfulness was against him. In 1880, he had only passed twenty-three birthdays and was too young to be listened to. So, Winnipeg continued to thrive between the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, even if a few more people did die from typhoid. Thus ended his first dream.

As to his second dream - to run street cars on Main Street - it took continual prodding to get the harassed City Fathers to the point where they gave their assent. They had plenty of other troubles. In April 1882, ice had swept away the bridge over the Red River at Broadway. Swarms of home-seekers had descended on an unprepared city. It had been necessary to rush in 1500 tents and seven car loads of ready-made houses to cope with the influx.

Perhaps it was to get rid of a nuisance, rather than their recognition of the transportation needs, that caused the Council finally to grudgingly yield a franchise. So, on 27 May 1882, the Winnipeg Street Railway was incorporated. The agreement stipulated that one mile of track must be laid within six months.

Mr. Austin easily met the deadline and on 20 October, the first horse car made a trial run. Success crowned the effort, despite the fact that the first car was derailed by a piece of wood across the tracks. It was easily replaced, despite being large enough to seat twenty-four passengers, and carry another two dozen standing. The ride was rough by today’s standards. Shock springs had not yet been invented, and the jolting and jarring was aggravated by mud dragged and dropped onto the rails by other vehicles crossing over, or even running along, the right-of-way.

On 21 October, a regular service began, utilizing four cars. When winter set in, sleighs were operated. Twenty fine horses bore the strain of hauling the citizenry of Winnipeg.

The first route was along Main Street, from the City Hall to Fort Garry, located at Broadway and Main Street. It was shortly after extended north to the C.P.R. tracks.

It could hardly be said that Winnipeg’s mass transportation era opened with a rush. The speed of the cars was restricted to six miles an hour.

Fares were ten cents cash or fifteen tickets for a dollar. In the winter the fare on the sleighs was only five cents.

The agreement for this service called for not more than thirty minutes between cars. Actually a five to seven minute service was given when four cars were in operation. When only two cars ran the service ranged from ten to fifteen minutes between cars.

The honor of driving that first street car went to a James Wilson, who signalled the beginning of Winnipeg’s first organized transportation with a loud “Haw” and a crack of his whip, to the accompanying cheers and cries from the enthusiastic crowd gathered to witness the auspicious event.

The first Street Railway Superintendent was George A. Young. The first Engineer was George McPhillips.

The stable of the Company was located on Assiniboine Avenue between Main Street (which had just been straightened when Fort Garry was demolished) and Fort Street. There was a two-storey roundhouse at the east end. Shelter was there for the horses. The cars, however, had to stand out on the rails due to the quagmire-like condition of Main Street or, risk being marooned when needed most. These soggy conditions resulted in many other vehicles using the tracks and caused the newspaper to comment: “The inveterate practice obtains of vehicles driving on the rails to the annoyance of the car drivers and the danger of passengers.”

Speaking of danger to passengers, the Free Press, on 15 December 1883, reported: “A horse-car horse developed blind staggers - a disease like insanity in a human being. The horse became ridiculous, snorted, reared, kicked, bit the conductor, then ended up by tipping the car over and trying to climb a lamp-post.”

A few months later a runaway horse-car horse was only captured when it tried to enter a store, through the window. No mention is made of any injured passengers.

Mr. Austin, a civic-minded man, courteously gave the Fire Department leave to use his road, where the ties were laid close together to prevent the horses from sinking their hoofs into the mud. It was not uncommon to see the straining, frothing steeds, hauling the rattling, red fire engines over the flat-tied roadbed in answer to the clanging summons from the Grace Church Firebell. The use of the tracks often gave the firemen the extra few minutes necessary to quench a potentially disastrous fire.

In 1883, Mr. Austin extended his service and ran a track along Portage Avenue. On 11 November, the first car ran along the new tracks to Kennedy Street as the Free Press put it “Harness and Whipple tree sang a song of progress.”

Later, in 1884, when the old Parliament Building was erected on Kennedy Street, south of Broadway, new car lines were constructed along Kennedy Street to Broadway. The same year, new tracks were built on Main Street from the north side of the C.P.R. tracks to St. John’s Avenue.

Now it was possible for sight-seeing Winnipegers to board a car at the Parliament Building, ride down Kennedy Street, Portage Avenue and north on Main Street to Higgins Avenue. There they left the car, crossed the C.P.R. tracks and presented their transfers on the car at the north side and rode along Main Street to St. John’s Avenue.

Winter weather was of major concern to the Street Railway Company in those early days. There were no “Sweepers” nor “Rotary Plows” to clear the tracks. Rails had to be abandoned once the snow and freeze up came.

Then the sleighs took over, with straw spread on the floor to help keep the feet warm. The driver, of course, was in the vestibule and exposed to the raw elements. When spring returned, the cars took their place again. There are several news items in the early years dating the clearing of the ice and winter’s rubble from the tracks. Even then, on the odd occasion, the weather played tricks. On 11 April 1884, a weekend blizzard strangled car service and it took a gang of men a full day to clear the rails on Main Street and Portage Avenue.

It is interesting to note that even in modern times, as recent as the late twenties, there is a real parallel for the spring of 1884. There had been a lovely spring. The weather was warm, the trees bursting into foliage, the snow had completely disappeared. Then, almost without warning, a howling blizzard buried the streets under a heavy layer of snow. The snow was so deep the cars could not break through. The “Sweepers” and the “Rotary Plow” had been put into storage at Fort Rouge, the motors had been taken out to be readied for the next winter. It was three days before the snow-fighting equipment, hurriedly rehabilitated, could get the street cars back to anywhere near normal operation.

But, to return to 1884. Main Street, that Spring, was a soggy morass. Pedestrians walked the tracks to keep out of the gumbo. It was such a boon to them, and such a nuisance to the car drivers, that Mr. Austin asked the City for a $1,000 bonus to compensate him.

I am not able to find that he ever received the bonus but, one thing seems certain, his request wakened the City Council to the long overdue need for the paving of Main Street. On 13 September, that same year, thirty-six cars of blocks and timber, together with sand and gravel, arrived in Winnipeg to start the job. On 7 October, Mayor Logan laid the first block.

But, street cars continued to profit because of Main Street’s condition for many years. A newspaper report of 1889 called special attention to that fact.

In the meantime, the Municipality of Kildonan raised $3,000 by private subscription in an effort to have the street railway extend its lines out there.

The next five years showed that the street cars had come to stay, but Mr. Austin was not satisfied. Winnipeg was growing and faster transportation was needed. Reports had come out from Richmond, Va., that they had started running an electric trolley line and the trolley cars attained a speed of thirty miles an hour. Immediately, Mr. Austin started hammering at the City Council to allow him to bring similar transportation to Winnipeg. From 1888 to the end of 1890, he pleaded, cajoled and demanded that he be allowed to run electric cars on Main Street. The static City Council, fearful of overhead wires, afraid (or so they claimed) that people would be electrocuted, refused to give him their permission. “Minneapolis had tried trolleys,” they said, “and horror of horrors - a horse had been killed!”

But, Winnipeg was growing and even the die-hards began to realize that something constructive had to be done about mass transportation. Finally, reluctantly, the City Council gave a guarded assent, not to run cars on Main Street, but to try them out “In the bush of Fort Rouge!”

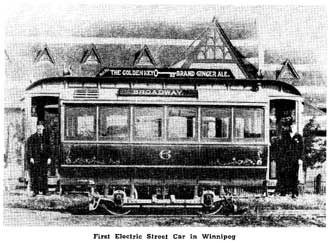

It wasn’t much, but it was a start. So, on 28 January 1891, from the spot where history indicates LaVerendrye first pitched his camp, the first electric street car in Winnipeg made its first trip. The car had to be hauled by horses over the Main Street Bridge. But, it was on the tracks on River Avenue and ready for its first run at 7:30 a.m.

At 7:31 a.m., Acting Mayor T. W. Taylor pushed home the switch to send the car on its way. Free rides were given that day to small boys and fat aldermen alike. The crowd cheered lustily as the car’s carbon lights flashed into life, dimming forever the weak, flickering light of the old oil lamps.

That first electric car was the first Edison car to be manufactured and operated in Canada. It was sixteen feet long and had two fifteen horsepower motors. At the time, many people thought the trolley was “just a passing fancy.” They were sure that cars operated by storage batteries would soon replace this contraption that needed overhead wires to make it run. Nevertheless, they accepted it.

On Dominion Day of that year, Winnipeg was all set to enjoy the holiday. Everyone who could, of a population now in excess of 25,000, was out to celebrate. It had been expected that a fleet of eight cars and trailers would be ready for the main event - a bumper picnic to Elm Park - but a strike delayed delivery of six cars. The job of carrying over 2,000 people fell on two cars and three trailers. Everybody wanted to travel between twelve and three. By crowding the cars inside, outside, on the platforms, roof and steps, two hundred and fifty passengers were carried each trip. The heavy loads overheated the journals. The cars were delayed waiting for them to cool out. Nevertheless they got the people to the Park. Then, at three-thirty, it started to rain, and, it continued to rain for three-and-a-half hours. Women in white picnic dresses were soon showing; every feminine feature. The people rushing home were squeezed beyond the usual delightful summer squeezing. It became a great day for rain, mud and mosquitoes. Mothers with babies abandoned their baby carriages and pushed into the cars. Enough perambulators were left behind to stock a store. Mr. Austin considerately had them gathered up and taken to his office where they were later claimed by their rightful owners. While it had been the Canadian Forresters who planned the picnic, it was undoubtedly the novelty of the electric cars that attracted the crowd.

Mr. Austin had proved that the trolley cars were a success. He was the pioneer. But, like many another trail-breaker, he failed to receive the benefits. In the franchise flurry that followed his success, legal battles kept him off the main streets of Winnipeg.

When, on 1 February 1892, the City Council passed by-law 543, giving James Ross and William McKenzie the exclusive right to operate electric street car service in Winnipeg, it was the fatal blow to Mr. Austin’s third dream.

On 26 July 1892, the first electric street car ran on Main Street, and the Winnipeg Electric Street Railway Company was born.

The first car, with Motorman William McDonald at the controls, started from the north side of the C.P.R. tracks, ran north on Main Street to Selkirk Avenue and west on Selkirk Avenue to the Fair Grounds at Sinclair Street. The roadbed was good and the car ran at a maximum speed of seven miles an hour. Passengers on that first trip included Mayor Macdonald of Winnipeg, the City Council, the Exhibition Director and the Press. The “No Smoking” regulation was evidently not in effect that day for Mr. G. H. Campbell, General Manager of the W.E.S.Ry.Co. handed out the best brand Havana cigars.

Horse-car in front of City Hall, 1885

The first Car Barn was on the south side of Portage Avenue, near Carlton Street. The first Barn Foreman was Mr. J. Wilkinson.

The office was on the east side of Main Street between Water and Notre Dame East, where a public parking lot now stands. Mr. Johnston was Office Manager, and Charlie Abbott was Ticket Clerk.

Mr. T. W. Glenwright was the Chief Conductor-a title that was later changed to Roadmaster, and eventually to Superintendent of Transportation. Murdock McDonald was Track Foreman.

Power for the Company was supplied by the Manitoba Electric & Gas Light Company from their Gas Works Plant.

The franchise granted under by-law 543 called for service to be in effect by 1 December 1892, on a Belt Line operating from Portage and Notre Dame, along Notre Dame to Sherbrook (then Nena Street), to Logan Avenue, east on Logan to Main Street, south on Main Street to Portage Avenue. Service was to be provided on Main Street from Higgins Avenue to Main Street Bridge, and from Sutherland Avenue to St. John’s Park. Portage Avenue was to have service from Main Street to Maryland Street. Selkirk Avenue had the inaugural service to the Fair Grounds.

The Council also had the right to demand a new line anywhere within the City Limits provided a population of at least four hundred persons over five years of age lived along each half-mile of line and within a quarter-mile of each side.

The new Company set out to meet the conditions. On 5 September, the same year, the first electric car ran on Main Street south of the C.P.R. Tracks. It ran from the City Hall to the C.P.R. Station - a trolley car and two trailers - then back along Main Street to Broadway. The newspaper report of that day reads: “The sound of the gong caused people to line Main Street from the C.P.R. to Broadway to watch the inauguration of a new era.”

It was a clear day. A Union Jack fluttered from the trolley pole. Waiting for the trolley to move off, a horse car, dwarfed by the modern vehicle, stood on a parallel track. The driver absently fondled the rein as he watched the over-capacity crowd jammed into the cars and overflowing onto the run boards. Perhaps he knew that the days of his service were numbered.

By 15 September, electric cars ran along Portage to Hargrave Street. On 12 November, the Belt Line began operation, and service was extended along Portage Avenue to Maryland Street.

By 1 December, Main Street had its service from Main Street Bridge to St. John’s Park, with that break at the C.P.R. tracks where the people scurried from one car to the other, dodging between passing trains and tripping and stumbling over the steam railway tracks.

Broadway had service too, from Main Street to Osborne where the old Fort Osborne Barracks was located.

To enable people to distinguish their cars the Main lines had special signs.

Broadway cars had a round Blue Light on the front of the roof. The Belt Line cars had a Red Pane of glass on the top front. Main Street cars had a Green Light.

Other lines had route signs.

The rolling stock of the Company consisted of seventeen single truck cars, helped out by six open trailers for summer use.

This was a period of competition. There were four car tracks on Main Street. Mr. Austin, striving desperately to keep his Company alive, ran his horse cars on the two inside tracks. The electric cars used the outer ones.

Overhead switches on the trolley wires were a source of continual trouble. Trolley poles left the wires more often than they stayed on at these switches. The poles, made of wood, frequently broke and caused long delays.

Thinking of this reminds me of a day, not many years ago, when a trolley came off at Portage and Main. It was right in the rush hour. The trolley base broke and the emergency crew arrived and started to clamber up to the roof of the car. As they reached the roof, a man on the street gave a startled yell! “My God,” he shouted, “Now they’re loading them on the roof!”

To get back to the old days; the trolley rope had to be tied to the brake handle inside the vestibule. The back window was always left open so that the conductor could lean out and put the trolley back on after its frequent de-wirements.

It was a common practice for passengers to “accidentally on purpose” pull the trolley off. Then, while the conductor was putting it back on, the passengers would move around in the car and how was the poor man looking for fares to tell who had and who had not paid?

The conductors carried a large punch which rang out when a fare was registered. If the punch knocked against anything or fell to the floor it was put out of commission - a fairly common happening as old records of the Company show. Fare collection was primitive. The tickets were cancelled by punch marks and cash fares punched on a cardboard. Fareboxes soon replaced this method.

Shovels, brooms and switch-irons were essential equipment in the winter. A stove in the centre of the car gave the only heat. The floors were covered with straw. Even gentle snowfalls gave trouble. The snow was like an insulation on the rails and often the conductor had to poke the switch-iron between the wheel and rail to make contact. The resultant blue-white flashing was blinding to watch. After heavy snowfalls, the crews had to dig their cars out of the drifts with shovels. During blizzards, horse-drawn plows cleared the tracks ahead of the cars.

The crew had no protection from the elements. The vestibules were open and motormen had to scrape ice and frost from the windows continuously to keep a “peep-hole” open. Heavy coats, thick, lined mitts, warm caps, and grey felt dolges lined with red flannel were standard wear.

Horse cars had the advantage those first winters. They could be put on runners. Electric car axles, brittle in the severe cold, broke easily. One can imagine the derision of the horse-car drivers as they passed stalled electric cars. Bitter rivalry raged between the two Companies. The citizens were partisan and jeers and gibes often led to hectic battles.

The riding public profited from the competition which led to a price war. Tickets sold at fifty for a dollar. The horse-car Company started it, the Electric Railway followed suit. There was even talk of a one cent fare.

The cut prices lasted as long as the legal battle for the franchise rights, which didn’t end until 1894.

But, costs were low in those days. The tracks were open and the paving charges almost nil. Regular motormen and conductors worked for ten and one half hours a day, six days a week. They were paid thirty-five dollars a month. Spare-men received five dollars less. The top wage averaged about fourteen cents an hour.

The year 1893, reported by the press as a “Period of Rapid Expansion,” actually seems to have been a period of waiting. Waiting to see what success existing lines attained - waiting to see the results of the price war between the two Companies - waiting to see the result of the legal battles over the franchises. That it was a slowed-down period is shown by the fact that a new by-law, modifying the conditions of by-law 543, was passed giving a one year extension to the construction period for additional lines.

For the W.E.S.Ry. Co. the year was not a complete failure financially, despite the two cent fares. Gross revenue showed a profit over gross operating expenses of $2,485, and rolling stock had increased to twentyeight cars.

17 March 1894 marked the final decision of the Privy Council, in the franchise dispute. It was in favor of the W.E.S.Ry. Co. The newspapers commenting said: “Mr. Austin has a host of friends who will sympathize with him in defeat, but all are happy that a final decision has been given. They now look forward for an improved service, possibly embracing Norwood, St. Boniface and St. James.”

But, it was a harsh spring. On 23 March, a terrific blizzard hit Winnipeg and strangled traffic. On 21 April, the Street Railway Co. had to keep a snow plow going all night to prevent the deep slush from freezing inches deep over the rails. The same day, angry North Winnipeg residents, tired of the procrastinations of the City Council, took matters into their own hands and cut a deep ditch under the street car tracks on Main Street, about where Manitoba Avenue now is, to run off water lying like a lake on the west side of Main Street. The water ran in the ditch like a mill race.

On 28 April, Mr. Austin and the W.E.S.Ry. Co. agreed to amalgamate. By 2 May, the terms had been agreed on. On the same date, the price war ended and car tickets returned to the charter rates of five cents cash (ten cents after eleven p.m.). Tickets were twenty-five for a dollar or six for twenty-five cents. Workmen’s tickets sold for eight for twenty-five cents, good up to eight a.m. and from five-thirty to six-thirty p.m. Childrens tickets were ten for twenty-five cents on school days.

On 12 May, the horse-car era ended. The W.E.S.Ry. Co. bought out Mr. Austin for $175,000. Among other things, the Company became the owners of River Park and about forty acres of land on Osborne Street, where the South Car House was later built. They also took over the four double-truck electric cars that Mr. Austin had been operating on River Avenue and to Elm Park. Car No.’s 40, 42, 44 and 46 were the first double-truck cars to run in Winnipeg proper.

Besides this, the W.E.S.Ry. Co. acquired the power plant of the old Company at Main Street Bridge. They immediately made plans to transfer the generators from the Gas Works Plant to this location which was of the latest design.

The horse stables were kept for three months. The horses, eighty in number, were sold by private sale. Forty-two men employed by the old Company were paid off.

Shortly afterwards, the Car Barns were moved from Portage and Carlton to Main and Assiniboine, a location that has remained constant to the present day. Mr. John Thompson was the first Barn Foreman. The office, also, was moved to the little red building at Main Street Bridge; a building torn down in 1951 to make way for a flood control pumping station.

But, while it now had possession of the tracks from Main Street Bridge to Elm Park, the new Company was still not able to give through service from the city to that point. Main Street Bridge was not considered strong enough to carry a loaded street car. However, pressure was brought to bear on the Civic Works Committee and, on 26 May, they approved a trolley line over Main Street Bridge. City Council batted the issue around until 23 October 1895. Then, though still fearful that someone would be electrocuted, they passed by-law No. 1035 giving approval for experimental service over the bridge to start when the bridge was strengthened enough to make it safe.

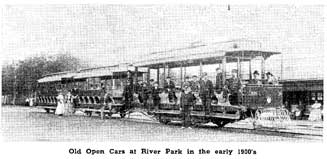

In the meantime, another Dominion Day had come and gone. It had been a fine day and ten cars and trailers carried load after load of holidaying Winnipegers to River Park and the newly-opened Fort Garry Park which centered around the gate of the old Fort at Main and Assiniboine.

By now, the need for more power was becoming pressing. As far back as 1888, the City Council had been asked to build a power plant on the Assiniboine River. The City Engineer pronounced the plan feasible. But the rivers were still traffic arteries and Ottawa controlled the water rights. If a power plant was built, they demanded the construction of a channel for navigation, an undertaking more costly than the power plant. Finally, in 1895, the W.E.S.Ry. Co. built a Steam Plant between Fort and Garry Streets on the banks of the Assiniboine and relieved them of the issue.

The plant had ten two hundred and fifty h.p. generators. The Chief Electrician was Mr. Herb. Somerset; the Engineer, Jack Bell. The first Fireman was Nick Ottenson, who later became a familiar figure as supervisor of River Park.

As for River Park itself, the new owners set out to convert it into the City’s major attraction. They put in new sidings to prepare for the 1896 summer traffic. (There was no service to the park in the winter; cars turned back at River and Osborne). To attract campers the old horse-cars were scattered along the banks of the Red River in Fern Glen Park; an area between River and Elm Parks on both sides of the river and apparently named as such by local custom.

In the same year, the Company started reaching out into Elmwood. Tracks were laid on Higgins Avenue and over the Louise Bridge. These tracks had to cross several steam railway tracks along Higgins Avenue and the conductor had to flag the cars over all the crossings. One of the old timers told me about a small blue keg of beer that was accidentally left on one of the cars. The conductor must have been a rather shrewd chap. He spotted the keg of beer as he got off the car to flag a crossing. Realizing that someone would be looking for it on the way back, he transferred it to a car going the opposite direction. Not very honest? Well, when the conductor went to pick it up at the end of his day, the other crew placidly stroked their moustaches and informed him the real owner had found it.

In 1897, tracks were laid on Sherbrook from Portage Avenue to Cornish. Mr. G. H. Campbell, the first General Manager, retired and Herb. Somerset, Chief Electrician, took over the post. The same year, Mr. T. W. Glenwright retired as Roadmaster and Mr. R. R. Knox took over the duties.

Mr. Knox, in a summary of his years of service, brought to light an interesting adventure involving Mr. Glenwright. While the latter was in his office at Main Street Bridge, counting the money taken in on the street cars, he was shot in the cheek by a robber. The same robber was caught a few days later, tried, convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for shooting a man on the ice of the Assiniboine River near Osborne Bridge. Thinking the man was dead, the robber covered the body with snow. It was probably this last act that saved the man from bleeding to death for, he came to, attracted attention, was rescued and eventually fully recovered from his ordeal.

Mr. Knox, familiarly known to his associates as Uncle Dick, served the Company well and faithfully for fifty years, rising eventually to Assistant to the General Manager in 1919, a position he held until 1 January 1942. He had started at the bottom and held the positions of Chief Conductor, Roadmaster, Transportation Superintendent in between. He never could get any liking for the automobiles that filled the streets in his later years. He rarely rode in one. To and from work he rode in the front of a street car with the motorman, a familiar figure to every man on the job.

On 4 January 1898, the Manitoba Electric and Gas Light Company was purchased by the W.E.S.Ry. Co. for $400,000.

The same year, the first car finally ran over Main Street Bridge on its own power. Now people could ride directly from the C.P.R. to Elm Park. In spite of all the apprehensions of the City Fathers no one was electrocuted. Nevertheless, people still asked if it was possible, and one good old soul put the question to a motorman. “Will I be shocked if I step on the rail?” Maybe his breakfast had ruffled his feelings for he answered gruffly, “Not unless you put your other foot on the wire!”

Actually the only record of an electrocution came years later at Charleswood. One of the farmers out there saw his horse go down in front of a street car and swore the car had killed it. Investigation showed that the horse, shod with iron horseshoes, had stepped on the rail as the car slowed down to stop. Its other feet were in swampy, wet ground, and this resulted in its getting a shock severe enough to kill it. The Company bonded the rails and no similar mishap has happened since.

It was in 1898 that the first record is found of a street car being burned by lightning. In one of the worst storms in Winnipeg’s history, starting with furious rain, thunder and lightning, then turning to snow, a street car at River Park was struck by a bolt of lightning and burned on 3 October.

In December 1898, first efforts were made to fit cars with fenders. Several types were given tests in ensuing years. It finally boiled down to two types; the Slemen fender which could be taken off and carried to the other end and the gate type which was fixed to the front of the car. The gate type did not come into use until the one-man cars came onto the scene. It was quite a common quip that, in one case you were picked up first and then killed, and in the other case you were killed first and picked up after.

Other communities were now looking for street car service from Winnipeg. The Municipalities of St. Anne’s and St. Norbert applied for electric lines in May of 1899. In July, the Manitoba Legislature considered a petition for electric service on the east side of the Red River from St. Boniface to St. Norbert, and from St. Norbert to Winnipeg on the west side of the river, with a branch line to St. Anne’s.

Also in July, the Company increased its rolling stock by the purchase of six new cars for operation to Fort Rouge and Elm Park, giving a ten minute service.

The same year, Mr. Somerset retired as General Manager and Mr. Harry Cameron took over. One of the first things Mr. Cameron did was to announce that new car barns were to be built at Main and Assiniboine, almost on the site of the Street Railway Rink where Winnipeg’s first hockey game was played back in 1890.

A little more track was laid this year, along Sherbrook from Portage to Notre Dame where it connected with the Belt Line. Osborne Bridge was also spanned and there was a direct connection from Broadway to River Avenue. New track was being laid on Main Street.

During this year, the Fort Rouge and Broadway route, commonly called the Loop Route, was placed in operation. The route ran two ways; the Fort Rouge from the C.P.R. Station along Main Street to River Avenue to Osborne Street to Broadway, to Main Street and back to the C.P.R. The Broadway cars ran the reverse way.

It was this year that Tom Flood joined the Company. He was a track worker first then a motorman on the street cars for fifty years until 1951, when he retired.

Tom Flood started work laying tracks, in the first concrete that had been used on Main Street. His job was drilling holes in fifty-six lb. steel rails to hold tie-rods; the rods that kept the rails properly gauged for distance.

“I remember it as if it was yesterday,” he said. “The engineer figured we wouldn’t need ties under the rails when they were set in concrete and held by tie-rods. Well, after we got the job done, they ran the cars over the line.” An Irish grin spread over his face. “You never felt anything like it. That Toonerville Trolley idea must have started right there. The lurching, swaying and heaving was terrible. It was like a ship on a rough sea. The City Engineer, Col. Ruttan, made a rush trip to Chicago to find out how they laid rails there. When he came back, we had to tear up the concrete and put ties under the rails.”

In 1900, the Company offices were moved to the Montgomery Building (Queen’s Hotel) at Portage and Main.

The Northwest Power Company was purchased by the W.E.S.Ry. Co. on June 9 the same year, and its power plant was dismantled. The purchase price was $126,947.50. It was part of a long-range plan to concentrate the production of power under one company and eliminate uneconomic surpluses of electricity. All of Winnipeg’s needs could be supplied from the Assiniboine Steam Plant, and at this stage, it took only one two hundred and fifty h.p. generator to supply every requirement after midnight and the ten generators at the Steam Plant had never been used simultaneously.

On 25 July, the W.S. & L.W. Railway (Winnipeg, Selkirk & Lake Winnipeg) was incorporated, to run to West Selkirk and the western shores of Lake Winnipeg, subject to the consent of the Municipalities it ran through. Stock was $150,000. The first Directors were: Colin Inkster, Hector Sutherland, Morrison Sutherland, N. W. Watson, J.D. Evans and R. S. Sutherland.

More about this later.

At this time the wages of trainmen were nineteen cents an hour.

In the latter half of the year, the financial position of the Company was good enough to declare the first dividend of 1.25% per quarter and from that time until 1915 dividends were paid regularly at various rates, the maximum being 33%, per quarter, maintained for fifteen consecutive quarters beginning in 1911 and ending in 1914.

By 1901, the population of Winnipeg had passed the 52,000 mark. Mass transportation had become big business. The Company now operated forty-two cars and carried 3,500,000 passengers in the year. A new Manager was at the helm, Mr. W. Phillips, formerly of North Toronto and Niagara Falls. He was a man who did not waste words as indicated by an incident of a few years later and told to me by Elmer Snider who joined the Company in 1902. A conductor whom Mr. Knox had had to discipline flew into a rage and attacked him. Next day, with only one comment, “Use this next time.” Mr. Phillips handed Mr. Knox a box. In it was an inch-thick, round, ebony ruler.

On 14 June 1901, the first private auto arrived in Winnipeg for a Professor Kenrick. No one then dreamed that this was the first nail in the coffin of the street cars.

With an age of expansion looming ahead, the Winnipeg General Power Co. was incorporated on 1 March 1902, to generate power on the Winnipeg River, with an initial $3,000,000 investment. It seemed an overly ambitious undertaking for existing needs, but, so had the Steam Plant in 1895 and it was already outdated.

Now a new transit organization had come into being. Also on 1 March, the Suburban Rapid Transit Company was incorporated to run from the western boundary of the city on both sides of the Assiniboine River to a point at, or near, the Village of Headingly. It was a sparsely settled territory but eager to get service.

The question of boundaries for the new company evidently caused some wrangling for an agreement on this matter was proposed on 11 October 1902.

By now the W.E.S. Ry. Co. was finding its transportation system needed more supervision. The old carefree days were on the way out. The street car service had grown up. The first two Traffic Inspectors were appointed, Sammy Slemen and Chris. Christenson. The old-time crews were faced with stricter regulations. They were being driven from the facilities they had enjoyed in the old Queen’s Hotel at Portage and Main.

“You fellows don’t spend enough to use this place as an office,” the proprietor told them.

The story was the same at the Tecumseh Hotel near Higgins and Main.

Schedules began to have a greater meaning. Regulations were beginning to be enforced. Extensions were planned.

The car tracks on Portage Avenue were extended to Sanford Street (then Windsor Street). The Main Barns were completed at Main and Assiniboine.

And, in this year, the Company started paying that 5% gross earning tax. It was not onerous then. Costs were low. There was no auto competition; no snow removal problem. In fact, the users of sleighs and cutters preferred to have the snow left on the streets. Besides, the Company had agreed to pay this in order to get an added ten years on the franchise, extending the first franchise from twenty-five years duration to thirty-five years.

In 1903, trackage was extended through St. James to Sturgeon Creek. On 2 November, the first street car operated in St. Boniface. The cars themselves had to be hauled into St. Boniface without benefit of rails, due to trouble with the owners of the Norwood Bridge. Heretofore, the only links between Winnipeg and St. Boniface had been the ferry in the early days and a toll bridge later. Now the W.E.S.Ry. Co. had obtained a forty-year franchise to operate in the Town of St. Boniface. Tracks were laid south of Norwood Bridge on Marion Street to Des Meurons; along Tache from Marion to Provencher; along Provencher from Tache to Des Meurons.

First electric street car in Winnipeg

Reaching into Elmwood, the Company extended its lines over Redwood Bridge, along Hespeler and Kelvin to Midwinter Avenue to the Louise Bridge; a route known as Griffin’s Spur. At the same time, they sent tracks probing along what is now Henderson Highway to Linden Avenue in East Kildonan.

Work had finally started on the W.S. & L.W. Ry. line running from Inkster and Main to the Town of Selkirk.

At the end of the year, the Company moved its offices across Portage Avenue to number 218 and 220 Portage, formerly a hat shop and a hardware store; later the Royal Bank Building.

In the city, tracks were laid along Dufferin Avenue and a loop was completed servicing the Exhibition Grounds with tracks along Arlington (then Brown Street), Stella, Sinclair and Selkirk Avenue.

A loop was built to eliminate the need for the “Y” for cars at Main and Higgins, taking in the square block surrounded by Henry, Austin, Higgins and Main Street.

1904 followed the pattern of 1903. Progress was the keynote. Even undertakers utilized the street cars, the Free Press, on 15 March, reporting that the mourners used a street car in a procession from Thompson and Sons to St. James Cemetery.

But, weather could still defy mechanical progress. On 27 March, a blizzard which even the old-timers said was “unparalleled” stopped all service. Nevertheless, man always digs his way out and continues on.

On 26 July, the Winnipeg General Power Co. and the W.E.S.Ry. Co. merged and became the Winnipeg Electric Railway Co.

Through the summer, tracks were extended further into East Kildonan out to Bergen cut-off. Tracks from Sturgeon Creek were extended to St. Charles (French Church).

Tracks were laid over Maryland Bridge and along Academy Road to Stafford Street. Sherbrook Street tracks were extended along Cornish to Maryland Bridge.

Preliminary work started on the construction of a subway under the C.P.R. tracks at Higgins and Main; passengers were still scurrying over the tracks.

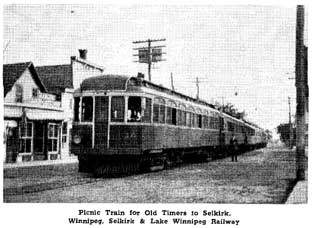

In the north-end the first service operated from Winnipeg to Selkirk. It was a steam railway, running from two to four cars, and carrying passengers, baggage and express. The first superintendent was Mr. F. D. Warren and the engineer on the first run was a Mr. J. Fingland. Mr. Norman Ross of 875 Grosvenor Avenue, Winnipeg, became engineer in 1905 and was also the first motorman on the first car to operate on the line when it was electrified in 1908.

There seems to be no existing history of a land transportation link between Winnipeg and Selkirk until the formation of the W.S. & L.W. Ry., except in excerpts telling of wagon, trading cart and horse travel along the Red River trail with the odd mention of bicycles in summer. In winter it was dog sled and sleigh.

Conversely there is quite a romantic history of water travel. Captain William Robinson, who came to Winnipeg in 1875, realized the possibilities of water transportation and gave up railway construction work to become a boat builder. He made Selkirk his headquarters but ran his boats through Winnipeg to the U.S.A. and from Selkirk to Lake Winnipeg. His flatboats and “logbooms” serviced all Canada as well as Winnipeg. This is the same Captain Bill Robinson who steered an expedition through 1000 miles of turbulent waters and cataracts along the Nile to the relief of General Gordon at Khartoum, unfortunately too late. He became President of the Northern Crown Bank and, when it was absorbed by the Royal Bank in 1918, he became a Director of the latter. He was a member of the Grace Methodist Church, Winnipeg Board of Trade, Manitoba Club, St. Charles Country Club, The Hunt Club, Canadian Club, Masonic Order, Board of Associated Charities, President of Associated Charities, in fact almost every prominent organization in the city.

Pioneering the steamboat industry on the Red River from Winnipeg to Selkirk in 1879, Capt. Robinson launched the steamer named after himself. In 1881, he launched the largest barge ever built in Winnipeg, also the steamer, Princess. By 1887, he had launched The Colville, The Ogema, The Lady Ellen, besides the barges, North Star, Wallace, and Saskatchewan.

Other boats were using the waterways, too. Steamboat transportation to the south, with Winnipeg at the northern terminal, actually predates the naming of the City by several years. It had a fifty-year history from 1859 when the Anson Northup steamed down the Red River until the Grand Forks ended steamboat transportation in 1909.

In 1872, the Hudson’s Bay Co. had plunged into river steamboat transportation. By 1874, they owned every boat that steamed up the Red, and, under the name, The Red River Transportation Co., ran regular schedules to Fargo from Winnipeg.

By 1878, the steamboat, along with the stage, was obsolete. Along the Assiniboine from the Red River to Brandon, river transportation continued for several years, but it was an outmoded form of travel. As a medium for mass transportation, the rivers did not fit into the scheme of things for the future.

The inauguration of the Winnipeg, Selkirk and Lake Winnipeg Railway tolled the elegy of river travel between Winnipeg and Selkirk. The steam railways drove the boats out of business to the south.

On 1 January 1905, the W.E.Ry. Co. obtained a thirty-six-year franchise with the Municipality of Kildonan.

On 26 October, the S.R.T. Co., operating from the western city limits, was purchased. The tracks on this line now extended to Headingly on the north side of the river.

Agitation for Sunday street car service which had been building up for years now ended in the City Council which voted it down.

1906 was a big year in Winnipeg’s transportation history. It marked the first transportation strike. On 30 March, 12,000 people gathered along Main Street as violence and disorder heralded the beginning of the strike. Two street cars were set on fire; one at Ashdown’s Store and one near the C.P.R. subway. The men wanted an increase in pay and the general public sided with the men. The Company brought in strikebreakers from the U.S.A. and housed them at the Seymour Hotel.

On 31 March, an Infantry Unit with a machine gun took up stations at Henry and Main. The N.W.M.P. under Lt. Col. Cameron loaded their rifles with ball cartridge. Mayor Sharpe read the Riot Act. There was some rioting and a police sergeant was hit over the head with a beer bottle. However, the crowd dispersed before the troops or N.W.M.P. charged. Eight days later, the Company granted a small increase in wages and the strike ended.

On 1 May, the Kildonan line was extended out to Foxgrove Avenue just north of the Knowles Home for Boys.

Service was inaugurated on Sargent Avenue on 1 June.

The new power plant at Pinawa started continuous operation on 13 June with a rated capacity of 15,000 k.w. It was so far in excess of the needs of the day that it became a common thing to hear the question: “What is the Company going to do with the power after they get it?” The Assiniboine Steam Plant was, of course, rendered obsolete, but, wisely, the Company kept it as a standby in case of emergency.

In the meantime, the W.S. & L.W. Ry. had been taken over as a subsidiary by the W.E.Ry.Co.

During the year, South Car House was built on Osborne Street with T. Tassman day foreman and E. Boughey on nights. Tracks were laid in Tuxedo to the City Park. Service was started on Pembina Highway from Corydon to Carlaw.

On 8 July, the vexing question of Sunday street car service was resolved. Eleven years after the first bill was shelved by the Legislature, service on the Sabbath was finally operated.

By 1907, there were sixty-nine miles of street car tracks in Winnipeg and its suburbs. New lines had opened up in the city proper and lines had been extended outwards in all directions. The steel rails were like the main strands of a spider’s web, drawing their sustenance from those who settled around them. There was no competition. Only a comparatively few individuals had a horse and buggy and a few had the new-fangled automobiles. The bicycle riders still used the old bicycle path out to Deer Lodge. All told, they were less than a drop in the bucket of transportation.

The Company bought sixty new cars and built its first single-end car. Air brakes were replacing the old hand brake. Tracks over Louise Bridge were extended to Talbot and Roland. Along Logan Avenue steel lines reached out to McPhillips Street. Street cars appeared on McGregor Street from Selkirk to Bannerman and along Bannerman from McGregor to Main Street. Arlington Street saw its first trolley cars operating from Portage to Notre Dame. The Sturgeon Creek Race track was favoured with a car line.

On 10 April 1908, the first electric street car operated from Inkster and Main to West Selkirk. Norman Ross was the motorman and L. E. McCall the first conductor and express messenger. The route followed the old Red River trail; a trail that had been used by Indians, explorers, missionaries, trappers and settlers. On board were W. Phillips, Winnipeg Electric Manager, and Superintendent Pettingill of Selkirk.

Transportation and the growth of the City kept parallel. Main Street received a face-lifting; concrete and asphalt replaced the cedar blocks. The C.P.R. subway at Higgins and Main allowed through service to the north end. Portage Avenue was growing up; Eaton’s big store was attracting crowds of shoppers. Elm and River Parks were entertainment centres with race track and professional baseball drawing the crowds. The Exhibition at Selkirk and Sinclair was in its heyday. Deer Lodge had Chad’s Hotel with bird and animal attractions. A big black bear out there could open a bottle of beer with its teeth and drink it faster than any man. Happlyland Amusement Park opened on Portage Avenue west of Home Street with a roller coaster as a major feature. Assiniboine Park opened to the general public in 1909. The C.P.R. had the world’s largest railway yards. The close-in flat-land was filling with homes, and, it was the street car rails that drew the suburbs in closer.

In 1909, the North Car Barn was built; a terminal for the Selkirk cars and a much needed storage place for the city vehicles. Another forty-seven cars had been added to the equipment. The next year, another twenty-six cars and three sweepers were added. Mass transportation was reaching upwards to its peak. The population of Winnipeg was 170,000 in 1910.

That the street railway was a major factor in the spread of the City is indicated by Mr. H. G. Stewart, Superintendent of Electrical Distribution, who recalls investigating a line of rails overgrown with scrub and poplar brush in the Silver Heights area. The rails were not laid by the Railway Company and were evidently “bait” in an early real estate boom.

In 1910, the Company was facing a second general strike of its trainmen. On 12 October, five men had been discharged for drinking while in uniform. The matter went to arbitration and the Board found in favor of the Company. On 16 December, the men went on strike to try to get their comrades back to work. It was the Christmas Season and the people were against the men. College boys ran the street cars and charged what they liked. The men lost the strike and many of them never got back to their jobs. The cars finally started running again on 1 January 1911, with many new faces at the controls.

Each year saw extensions and additions to the City lines, but by 1912, all the major routes had been laid out. In this year, the Mill Street Stand-by Steam Plant went into operation and the Assiniboine Steam Plant was dismantled. Street cars were operating wherever there was sufficient demand. Portage and Main was the heart of the system and rails radiated like wheel-spokes from this centre.

On 1 July 1912, the W.E.S.Ry.Co. obtained a thirty-year franchise with St. Vital.

One year later, on 22 July, a thirty-year franchise with Fort Garry was signed.

The transit company grew rapidly and built a sky-scraper to house its offices. From 1913 to 1955, this was the “Headquarters.” New cars were added to the fleet year by year. In 1914, war halted progress. By this time, Stony Mountain and Stonewall had been linked with the city by extensions to the W.S. & L.W. Ry. line. St. Vital had service out to Berrydale. There was service through Fort Garry to St. Norbert and the Agricultural College. Three hundred and twenty-three street cars were in service when the war made further purchases impossible.

By 1914, doors were being installed on the rear vestibules of the big cars. The pay-as-you-enter system went into effect.

Old open cars at River Park in the cearly 1920s

1914 provided the only instance where street cars failed to operate when demanded. That place was Arlington Bridge. The City had applied for service over this bridge and the Utility Board had ordered that tracks be laid. This was done. But service was impractical and unsafe. The men refused to run the cars over it. Only one trial trip was ever made. The bridge was too high for its purpose. It had been bought at an auction at Darlington, England from the Cleveland Bridge and Iron Works. The bridge had been built to span the Nile River in Egypt, but the people who ordered it failed to take delivery. It was transported over here and erected across the C.P.R. tracks at what were then Brown and Brant Streets in 1910-1911. The steep grade of its approaches was too much for the street car men.

Prior to 1914, there was comparatively little competition from the automobile. In that year jitneys commenced to operate in Winnipeg. By 1915, six hundred and sixty-three cabs were on the streets. These vehicles did not give a regular and dependable service. For the most part they operated in the rush hours only and on heavily travelled routes, charging a five cent fare. They greatly affected the revenues of the Railway Company, creating estimated losses in revenue of $374,377.00 in 1915; $284,582.00 in 1916; $367,079.00 in 1917, and $30,736.00 up to April 1918, when they were eliminated by the “Jitney Agreement.” The City passed a by-law setting a minimum rate of twenty-five cents per person carried in a taxi. This effectively stopped this type of competition.

In return for the elimination of the jitney competition the City demanded extensive improvements in the W.E.Ry.Co. rolling stock, and also major alterations in its power system to mitigate electrolysis. The Company also agreed to operate motor buses on Westminster Avenue as part of its regular city service. The Agreement called for the expenditure of $900,000.00 in three years. The transit company actually spent double that amount, or $1,800,000.00, and a further $500,000.00 for new sub-sections and the mitigation of electrolysis.

In 1916, automatic signals for passing tracks came into effect; the first one being at the St. James subway. Later they were installed on other lines.

When 1918 arrived there were three hundred and forty-one street cars, but 1 May of the same year marked the first step in the transition from rail to rubber. Four twenty-one-passenger gas buses operated on the Westminster route. The first bus driver was Mr. Jack Allen, a name perhaps better known to the racing, than the riding public, for, he later owned and ran several race horses at Polo and Whittier Parks. The next bus routes were Stockyards and Notre Dame.

A three-day strike in May 1918, and the six-week strike of 1919 are only mentioned in passing. Nevertheless, they showed the impact on a city’s economy that can result from the loss of mass transportation facilities.

On 19 May 1920, River Avenue, the route that had provided the beginning of electric street car service in Winnipeg, was abandoned. The same year a disastrous fire destroyed the Main Car House and twenty-one street cars.

From then on, the street cars began to give way. Short “feeder” lines and lightly used suburban routes converted to rubber. Economy measures transformed the street cars. Two-man cars became one-man cars, first in the outskirts, then reaching through the heart of the city.

Yet extensions were still taking place. Great Falls construction started in 1921, and the first power came through in 1923. Street car lines reached further out Academy Road to connect with the Charleswood route. Rails were pushed further out on Notre Dame. Bus service started on the Cathedral route. Sargent was extended to Valour Road. A bus service ran south from Berrydale and St. Mary’s to the Sanatorium.

In 1922, the Town of Transcona was linked to Winnipeg by bus transportation. That sprawling town to the northeast of the City had been born of the needs of the Canadian National Railway and had only a limited train service to Winnipeg. On 7 July 1914, the W.E.Ry. Co. had announced they were going to start work on a street car line to the town but the war stopped this program before it got started.

In 1922, Mr. Lange, whose home was in International Falls, but who ran a sight-seeing bus from the Royal Alexandra Hotel in the summer months, decided to put his bus to further use and tried operating a two-hour service to Transcona. At first it was a fizzle, but only because he ran on the same hours as the trains. He switched the times and business boomed. For a time the line was unnamed, but in October 1924, it assumed the name Transcona Transportation Co. and ran two to three buses.

The first regular driver was Mr. H. L. Erhardt.

In 1925, the Interurban Services was incorporated and bought out Transcona Transportation Co. On 5 August 1926, the W.E.Ry.Co. took over the line.

Due to law suits resulting from an accident at Smith and Graham, the Interurban Services went out of business on 12 January 1928 and the Transcona line became part of the regular bus service of the W.E.Ry.Co.

In June 1941, it was taken over by the White Ribbon Bus Lines under the management of Mr. William Dunn, a former W.E.Ry.Co. bus driver.

On 15 September 1925, bus service was inaugurated in the outskirts of Elmwood. A bus service started on St. Anne’s Road in St. Vital. On 3 December, the first street car ran over the modern Provencher Bridge giving a new link with St. Boniface.

It was also in 1925 that Winnipeg had its greatest unsolved robbery. The Street Railway payroll, some $87,500.00 in cash, was snatched in an unparalleled daylight hold-up. The perpetrators of the robbery have never been caught.

The same year saw one-man cars in regular service for the first time, although there was a one-man car that ran back and forth over Maryland Bridge for several years starting in 1904. No fares were collected on this car which operated purely as a convenience for people crossing the bridge.

In 1926, on 1 November, the Hudson’s Bay Co. opened its new store at Memorial Boulevard and Portage. The Boulevard was opened to street car traffic on 18 November.

It was the age of conversion for the Transit System. The mournful thirties saw the street cars give way more and more rapidly to buses. Even so, 1934 was the peak year for street car trackage with a high point of 121.15 miles. Then it started to shrink. From year to year, changes mounted up. In 1937, the last street car operated to Selkirk on 1 September, and bus service connected that town with Winnipeg. The W.S. & L.W. Ry. turned over its operations to the Beaver Bus Lines in 1948 and they have operated this line ever since. Stonewall service was discontinued in 1939 and its first bus service began on 6 May.

A new type of transportation began in the city in 1938. The first trolley coach ran on the Sargent route on 21 November. Buses were well-established but competition demanded more. There were 28,000 autos on the streets in the middle thirties and trackless trolleys were introduced to meet the challenge. At the inaugural ceremony the story leaked out “on the air” of the man who burst into the General Manager’s office to tell him the service was worse than in Biblical Times, then at least, the complainant said, “A man was able to ride into Jerusalem on his ass!”

The Second World War gave the street cars a respite. True, some city lines disappeared, such as William Avenue, Notre Dame West and St. Boniface. But now the Armed Forces needed all the raw materials. Throughout the war the crowded City taxed the transportation facilities to the limit. The peak was reached in 1946 when 105,000,000 passengers rode the street cars and buses.

As the halfway mark of the century was passed, the Manitoba Government exercised its right by taking over the power developments of the Company at Seven Sisters and Great Falls. The Transportation Utility became first the Greater Winnipeg Transit Company, then the publicly owned Greater Winnipeg Transit Commission.

On 19 September 1955, the street cars made their last run, giving way to the modern diesel, gas and trolley buses.

Two other phases of Winnipeg’s transportation history should not be overlooked. One is cab transportation. The other is suburban transportation by bus.

Our present taxicab industry is a development from the livery business of former days. The first by-law dealing with cabs was one regulating their stands, by-law 124, passed 17 May 1880. By-law 135, passed 7 March 1881, regulated the cabs themselves. On the same date a by-law to regulate Livery Stables was passed, but preceding this, a Mr. Landrigan had, on 9 May 1872, announced a cab service to start within a week. On 7 May 1874, the City Dray and Express Co. advertised they would transport passengers to any part of the city and vicinity. Livery men played a prominent part in the age of horse transport.

In its early days it was an individualistic business, mostly used by people of means and more or less luxurious tastes. It was a rather unstable business until 1935 when the Public Utility Board took over the licensing and regulating of the industry.

Yet as far back as 1899, which is the first year the City License Department has any record of, there were 138 licensed cabs, In 1917-18, 583 cab licenses were issued. Now it is restricted to 400 licenses. The industry has assumed the characteristics of a public utility in that it provides a service essential to the needs of a city. It is available to all who may demand it. The standard of its equipment has developed from the old-horse-drawn cab or hack to the modern auto in which public safety and convenience are major considerations.

The proper function of a taxicab was and is, in a special, rather than a mass form of transportation. It met demands that the rigid routes and schedules of street car and bus could not meet. Its mobility and convenience have been the characteristics that gave it a proper place in the City’s transportation.

It is this same characteristic that has brought the privately operated automobile into such great use.

In 1913, there were only 3,181 autos registered in Winnipeg. In 1953, there were 65,511. It was estimated this figure reached 92,000 in 1957. This is certainly a phase of transportation in Winnipeg that has changed the mass transportation picture very drastically. It has made people independent. They used to beg and demand car and bus lines along their streets - they were happy when a car or bus stop was in front of their homes. Now they demand that the buses be taken off their streets and the stops be placed at other locations. They want the street space for their cars - both to run on and park on.

Picnic train for old timers to Selkirk.

Winnipeg, Selkirk & Lake Winnipeg Railway

Finally, bus transportation from the city to rural points began in a quiet manner but expanded rapidly. It grew out of the tremendous advances in communication media which, in turn, made rural communities conscious of their isolation; a condition for which transportation was the most obvious cure.

The first regular rural bus service was started by Mr. Ira A. Moore, now a Provincial Government Highway Inspector. In 1922, he operated an International Speedwagon between Winnipeg and Portage La Prairie.

The same year, a bus service between Winnipeg and Teulon was started by the late Mr. Harry Pitts. In the Fall of 1924, Mr. P. C. Mallory used a seven-passenger car as a bus between Winnipeg and Carman. In 1925, Mr. Pete Homenick, who still operates the Red River Motor Coach Lines, established a regular service between East Selkirk and Winnipeg. In 1926 and 1927, he extended his service to Tyndall and Beausejour. By 1930, he had reached out to Lac Du Bonnet. Old Timers still recall Mr. Homenick’s old Model T Ford with the back cut out, that he used to park on Hargrave St. Rumour has it that Eatons in order to get rid of this eyesore, donated property for the first bus depot. Could be! Prior to this the Majestic and McLaren Hotels had been the bus terminals.

In 1926, Inwood and Chatfield were linked to Winnipeg by buses operated by the late Mr. Hurshman. It took him three days to make his first trip from Inwood. He had to lay logs in corduroy fashion to get over the worst stretches. He was a man to overcome obstacles-a true example of rags to riches, as illustrated by the fact that he attended his first Board Meeting of bus operators in ragged clothes, with the seat out of his pants and the barnyard on his shoes. When he retired to the West Coast because of ill-health he said “Goodbye” wearing a $125.00 suit and carrying a gold-headed cane.

In the Spring of 1927, two brothers, D. Brown and J. W. Brown, started a service to Carman with two seven-passenger cars. Later in the year, Mr. Garry M. Lewis, bought D. Brown’s share of the business and the Grey Goose Bus Lines was born. Service was extended to Morden in 1928, when Mr. Elmer Clay, an early partner in the Grey Goose Bus Lines Co., purchased the holdings of the other brother. Manitou and Notre Dame de Lourdes were linked to the Company in 1929. Crystal City followed in 1930. The next year Treherne, Glenboro, Killarney and Wawanesa were added to the network.

The Clark Transportation Company linked the northwestern part of the Province to Winnipeg, with buses running to Dauphin, Neepawa and Yorkton. The story is told that when this Company started they had a local firm build a bus body to put on a truck chassis. It was a great job, until they went to install the seats, and found they had no room for the aisle. They eventually solved the problem by making the body a foot wider.

In 1930, the Royal Transportation Co. under the late Allan Ramsay, gave Winnipeg service to Gimli, LaBroquerie, Steinbach and Emerson. The same year the Eagle Bus Lines was organized by Mr. Harvey Duguay and operated to St. Malo, later adding St. Anne and East Braintree.

Other bus lines connect other communities, with Greyhound and Moore’s being prominent names. But by 1936, the bus industry had reached its maturity, with a network reaching to all parts of the Province. And - the hub of the system is here in Winnipeg.

Year

Event

1877

Omnibus service attempted. Abandoned after one day. (Customs Building to Point Douglas.)

1882

21 October. First Horse Car (Main Street, City Hall to Broadway).

1891

28 January. First Electric Car (River Avenue, Main to Osborne).

1891

2 July. First cars to River Park.

1892

1 February. Winnipeg Electric Street Railway incorporated. First franchise to operate Electric Street Car service in Winnipeg. Street car lines placed in operation:

Main Street from Higgins Avenue to Main Street Bridge

Main Street from Sutherland Avenue to St. John’s Park.

Selkirk Avenue to Sinclair Street and Exhibition Grounds. (Terminal C.P.R.).

Broadway from Main to Osborne Street. (Terminal C.P.R. at Higgins Avenue).

(Old Fort Osborne Barracks.)

Portage Avenue from Main Street to Hargrave.

First car on Main Street 26 July. Service south of C.P.R. started 5 September.1893

Portage Avenue service extended to Maryland Street. Belt Line route in service-Notre Dame West, Sherbrook, Logan and Main Street. Tracks laid Osborne & Broadway to Osborne Bridge. Tracks laid St. John’s Park to Main and Inkster.

1894

Last Horse Car operated. (A. W. Austin Company bought out by W.E.S.Ry.Co. in Spring of year. Tracks laid on William Avenue from Main to Sherbrook.

1895

The Assiniboine Steam Plant commenced operating. River Park site bought by Company. South Car Barn site purchased by Company. (40 acres.)

1896

Tracks laid on Higgins Avenue from Main Street to Louise Bridge.

1897

Tracks laid on Sherbrook Street from Portage to Cornish

1898

First car operated over Main Street Bridge, giving through service from C.P.R. Station to River Park. Tracks laid Main Street Bridge to Norwood Bridge.

1899

Tracks laid on Sherbrook from Notre Dame to Portage. Also Osborne to River Avenue.

1900

Office moved from Main Street Bridge to Montgomery Building, downtown at Portage and Main

1901

Tracks laid River Park to Elm Park. 42 cars in operation. 3,500,000 passengers carried.

1902

Winnipeg General Power Company incorporated with $3,000,000.00 investment. First Traffic Inspectors S. Slemen and S. C. Christenson. Street car tracks extended along Portage from Maryland to Windsor (now Sanford). Main Barns built.

1903

Track extended through St. James to Sturgeon Creek. Service extended into St. Boniface

Griffin’s Spur-From Main Street via Redwood, Hespeler, Kelvin, Midwinter to Louise Bridge. Track in East Kildonan to Linden Avenue (Henderson Highway was then on map as Bird’s Hill Road).1904

Winnipeg General Power Company and W.E.S.Ry.Co. merged and became Winnipeg Electric Railway Company. Track in East Kildonan extended to Bergen cut-off (C.P.R.). Preliminary work started on subway for C.P.R. tracks near Higgins and Main. Tracks extended along Portage from Sturgeon Creek to St. Charles (French Church). Tracks laid Maryland Bridge and Academy Road to Stafford.

1905

Tracks extended from St. Charles to Headingly. S.R.T. became subsidiary of Co. Tracks extended along Main Street to North City Limits.

1906

Pinawa Plant in operation. South Car House built. First Sunday Street Car service approved. East Kildonan tracks extended to Foxgrove Avenue, East St. Paul. Two week long strike-Two Street cars burned by strikers. Winnipeg, Selkirk & Lake Winnipeg Railway (Steam) taken over by Company.

1907

Street car tracks in use in City and St. Boniface and suburbs - starting date of some lines not known: 69 miles, including 16 miles S.R.T.Co. Main Street from North Limits to Norwood Bridge. Portage Avenue from Main Street to Headingly. Bannerman Avenue, Main to McGregor, McGregor to Selkirk Avenue. Selkirk Avenue, Main to Sinclair. Dufferin Avenue, Main to Sinclair (Possibly installed in 1903). Loran Avenue to Blake Street. William Avenue, Main Street to Sherbrook (then Nena Street). Notre Dame West from Portage to Arlington. Sherbrook Street from Logan Avenue to Maryland Bridge. Broadway-Main Street to Osborne. Osborne Street and Old Pembina Street from Broadway to Elm Park. (Pembina Street is now Osborne Street.) Corydon from Osborne to Lilac, Grosvenor, Stafford, Academy to Maryland Bridge. Pembina Highway from Osborne and Corydon to Grand Trunk Pacific tracks. Arlington from Portage to Notre Dame. Higgins Avenue from Main Street to Curtis Street. Griffin’s Spur, Redwood & Main, via Redwood, Hespeler, Kelvin, Midwinter to Louise Bridge. St. Boniface - Main Street Bridge, Norwood Bridge, Marion, Tache, Provencher, to C.N.R. Station, Provencher and Des Meurons. River Avenue-Main Street to Osborne. Charleswood Line from St. James Street & Portage to Charleswood (Using C.N.R. tracks over St. James Bridge until 1924). Spur lines off St. Charles Line to Race Track on North side and St. Charles Country Club on South side.

1908

Tracks extended on Logan from Logan Avenue to make C.P.R. shops loop via Quelch, Gallagher and Blake Street. Tracks laid from Main and Euclid to Sutherland and Higgins. Tracks on Talbot frorn Midwinter to Roland Street. First electric car operated from Town of Selkirk.

1909

North Car House built. Tracks laid on Sargent Avenue from Sherbrook to Arlington. Tracks laid on Logan Avenue from Blake Street to Keewatin. Higgins Avenue extended from Curtis Street to Louise Bridge.

1910

New trackage-Marion Street to Traverse. Pembina Road from G.T.P.Ry. tracks to Lilac. McPhillips from Exhibition Ground to Logan. Notre Dame from Arlington to Wall Street.

1911

New trackage-McPhillips completed from Selkirk to Logan. Marion extended to Des Meurons. Princess Street from Higgins to Portage Avenue. Ellice Avenue, Kennedy Street and Sargent to Sherbrook. Selkirk Avenue from Sinclair to McPhillips.

1912

Mill Street Stand-by in operation replacing Assiniboine Steam Plant. New trackage-Work started on tracks to Stony Mountain and Stonewall. Mountain Avenue from Main to McGregor. Donald Street from Portage to Broadway. Arlington from Notre Dame to William. Des Meurons from Marion to Provencher. Broadway form Osborne to Sherbrook. Arlington Bridge opened (Known as Brown & Brant Street Bridge). (Only one street car ever operated over this Bridge due to steep grades. Men refused to run cars over it). Academy Road-Stafford to Guelph.

1913

Winnipeg Electric Railway Chambers built. Kelvin-Talbot route replaced Griffin’s Spur which was abandoned. Elm Park to Parker wye installed. Tracks laid on Academy - Guelph to Ash. Track completed to Stony Mountain. (WS&LW Ry.) Tracks laid on Pembina Highway from Elm Park to Agricultural College. Tracks laid on St. Mary’s Road to Berrydale.

1914

Tracks completed to Stonewall. (WS&LW Ry.) Clifton Loop installed. (Taken out in 1927.) Tracks laid on Arlington from William to Mountain. Tracks laid for Rifle Range spur, St. Charles. Tracks laid on Johnson Avenue, Kelvin to Levis. Tracks laid to St. Norbert on Pembina Road (Now Highway)

1915

Tracks laid on Marion from Des Meurons to Stockyards. During 1915 about 5,000 rail bonds were stolen off the Selkirk line from Kildonan to Mapleton. Trolley wire stolen from Rifle Range spur. After trial run over Arlington Bridge men refused to operate cars. (City Council had petitioned the Utility Board for service over the Bridge.)

1916

First automatic signal for passing tracks used at St. James subway.

1918

Morse Place line completed to Munroe from Johnson and Levis. 1 May. First gas bus operated on Westminster Route. (J. Allen was driver.) Tracks extended on Sargent from Arlington to Garfield. 1920-River Avenue street car line abandoned, 19 May. Bridges spur built (Back of Shea’s, Broadway and Osborne.)

1921

Great Falls construction started.

1922

Academy Road line extended from Ash to Lindsay Street.

1923

One man cars on Kelvin and on Pembina. Academy extended from Lindsay to Kenaston. Notre Dame West extended Wall Street to Midland Street. Bus on Cathedral, east of Main Street.

1924

One man cars on St. Norbert and Agricultural College routes, 2 September. 24 March - Bus service from Victoria to St. Charles. Academy line extended Kenaston to Doncaster Wye (Fort Osborne Barracks). Safety cars on Charleswood 3 March. On St. Charles & Headingly 24 March. Sargent extended Garfield to Valour Road. Bus service at the end of St. Mary’s Road.

1925

16 April - bus service Deer Lodge to Victoria Street. One man cars on St. Mary’s Road 2 April. East St. Paul 26 May. Sargent, Notre Dame and Arlington 11 June. Bannerman, 15 August, St. Boniface 24 August. First Street Car over Provencher Bridge, 3 December. First treadle door cars in service 13 December. Bus service on Talbot from Roland to Kent Street, 15 September. Bus service on St. Anne’s Road, 3 November.

1926

Bus service on River Avenue, 23 November. Memorial Boulevard opened 18 November. Car service to Broadway inaugurated. Hudson’s Bay Co. new store opened 1 November at Portage and Memorial Boulevard.

1927

16 May - Buses on Ellice Avenue. 16 May - Morse Place-Kildonan-Broadway converted to one man operation. 30 June - Bannerman cars running on McGregor Street only. Bus on Atlantic replaced car on Bannerman Avenue. 17 September - Bannerman cars discontinued. 18 September - Selkirk route now operating alternate cars to McGregor and to McPhillips. 11 October - Buses on Arlington. ? Corydon route extended from Lilac to Wilton.

1929

Notre Dame extended from Midland to Worth. Stafford extended from Grosvenor to Lorette. Pembina tracks extended Lilac to Carlaw.

1930

7 May - Headingly cars discontinued. 22 August - Headingly bus service discontinued. Cathedral bus replaced Atlantic bus - service both sides of Main Street.

1932

1 June - Buses replaced street cars on Logan, Main to Arlington. Buses as well as street cars on Agricultural College Route.

1933

22 May - Street cars off, motor buses on Sherbrook. 1 March - Buses replaced street cars on Mountain-Dufferin Loop. 16 November - Motor buses replaced street cars to St. Norbert.

1935

Motor buses replaced street cars on Charleswood, 16 September. Jefferson bus service inaugurated 23 September.

1937

Motor buses replaced street cars to Town of Selkirk, 1 September. Motor buses replaced street cars to North Kildonan and East St. Paul, 25 May.

1938

First trolley coach in operation on Sargent route, 21 November. Motor buses replaced street cars on Elmwood route, 6 November.

1939

Street car operation to Stonewall discontinued. (H. Henteleff started with bus 6 May. Motor buses replaced street cars on William Avenue, 16 December. Motor buses replaced street cars in St. Boniface 18 December. Motor buses replaced street cars on Notre Dame from Arlington to Keewatin on 18 December. Trolley coaches replaced street cars on Logan route, Notre Dame to Arlington to Logan to Keewatin, 18 December.

1941

Trolley buses replaced motor buses on Notre Dame from Arlington to Keewatin on 16 January.

1944

Motor buses replaced street cars in Fort Garry, 5 September.

1946

Trolley coaches replaced motor buses on Salter route, 21 January.