by Chris Vickers *

MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1944-45 Season

|

The notes which follow are the work of an amateur. I am fully aware of the possibility that all of the conclusions, speculations and suggestions made could be refuted by true scientific inquiry. This would not be unwelcome, for the main purpose in compiling the material was the hope that some day the National Museum of Canada and the various scientific institutions in the province would attack the intriguing problems of our archaeology. The University of Manitoba, the Manitoba Museum Association, the Historical Society of Manitoba, the Natural History Society, the Government of the Province of Manitoba and others should be aware of the rich story of our past, and should give earnest consideration to securing the necessary funds and properly trained personnel to interpret that story.

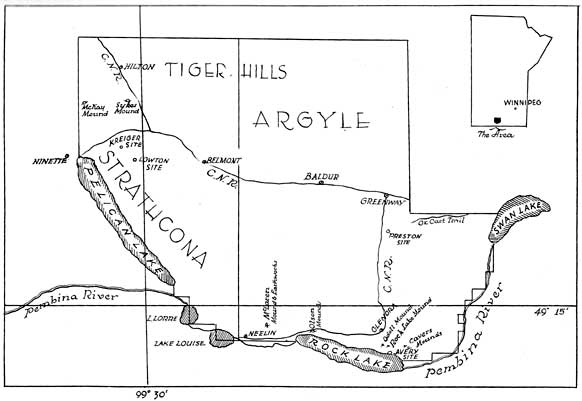

If any merit appears in what follows, most of the credit must go to many friends. To members of the Manitoba Museum Association who are always helpful and kind. To farmers who always give permission to examine sites on their land. To Dr. Douglas Leechman of the National Museum of Canada who very kindly revised the manuscript. To Mr. N. O. Finnigan, principal of the Baldur School, who prepared the map of the area, and to my son Ivan Vickers who has been my constant companion during many years of archaeological study and who at sixteen years is an equal partner in all our work.

Geographically speaking the area covered in this paper is encompassed in the rural municipalities of Argyle and Strathcona. These municipalities are in the south-central portion of the Province of Manitoba, about fifteen miles north of the international boundary, and at latitude 49.15 north and longitude 99.30 west. The chief topographical features being Rock and Pelican Lakes, which form in a large measure the southern boundary of the area, and the Tiger Hills which cover most of the northern portion from east to west. To the geologist the district has many points of interest. The deep wide valley in which the two lakes lie is part of the old drainage system of the glacial Lake Souris. The Tiger Hills are a terminal moraine of the ice sheet. The area between the two main topographical features is dotted with countless small lakes and water laden depressions. It is today, and likely always has been a hunter's paradise.

Only periods of severe drought could deplete its game resources. Since 1880 it has supported the white man with, on the whole, excellent returns from mixed farming. Judging from the archaeological remains found in the district, it is evident that the red man found it, for a time at least, equally inviting. The remarks that follow are not to be considered as a complete survey of its archaeology, they must not even be considered complete in regard to any one site, rather they are a report of progress, prepared in the hope that the bare outline here presented will stimulate further action by organized scientific institutions.

The direct historical approach combined with the Midwestern taxonomic method have, in the opinion of this writer, become effective tools in reconstructing the story of the past. M. W. Stirling of the Bureau of American Ethnology has well said, "Archaeology should primarily constitute an attempt to reconstruct ethnological and historical facts." To work from the historic to the prehistoric has been the principle that has guided our survey of the area. The belief was held that if the camps of recent hunting peoples could be isolated, then, in the words of Wedel, "a whole series of sites could soon be removed from the category of unknowns."

It is the misfortune of the archaeologist that most of southern Manitoba was occupied at the dawn of the historic period (early eighteenth century) by the nomadic Assiniboine. The camp sites of this tribe were often small and occupied for a limited time only, with the result that the material left for the modern worker is limited and frequently insignificant. It would seem safe to assume, however, that the Assiniboine hunters were periodic occupants of the area. This does not exclude the possibility of temporary occupancy by other Siouan tribes, particularly the Hidatsa, with an odd visit from the Cree. Documentation of part of this assumption will be found in the Journal of Alexander Henry the younger.

Writing under the date of October 14, 1800, he states: "I hired Nanaundeyea to go toward the Ribbone lakes [1] in search of the Crees and Assiniboines, and try to prevail upon some of them to come to our establishment. (Henry Thompson Journals by Elliott Coues Vol. 1, Page 119.) Additional reference is made on pages 119 and 120 in the following remark by Henry: "We observed a thick smoke toward the Ribbone lakes, which makes me believe my messenger will find the Indians there." With reference to particular sites, the writer is of the opinion that the Kreiger Site (S.W. 27-5-16) and the Preston Site (N.W. 26-4-13) were occupied by recent hunting peoples. Large, well-made arrow points and crude grooved stone hammers are characteristic of both. White contact material is present in the form of gun flints, glass beads and the lid of a copper kettle of the trade type.

There is not any doubt that these sites were occupied by some of the historic tribes within the historic period. To identify the tribe, however, is a problem beyond the resources of a single worker. Accurate and detailed study of the historic and protohistoric Assiniboine is an urgent need in the anthropological background of southern Manitoba. They were the first of the Siouan tribes to reach the great northern plains, and the possibility that our Manitoba mounds were built by a people directly ancestral to them is a speculation that awaits inquiry. Irrespective of the answer, the archaeology of the historic and protohistoric Assiniboine may well hold the key that will open wide the door to the prehistoric background in southern Manitoba.

On the level plain north of Rock Lake there are seven burial mounds and one extensive earthwork. These mounds are scattered along the whole of the north shore of the lake and extend westward above the valley of the Pembina River. The possibility of additional mounds is not precluded; part of the plain north of the lake is heavily wooded with a comparatively recent growth of poplar and oak; and the likelihood of further discovery is good. Most of the mounds have been partly excavated. This, so far as we can learn, was done mainly by curio hunters during the last two decades of the past century; and we have not been able to ascertain what material, if any, was removed. The only scientific excavations made were by Dr. Henry Montgomery in 1907 on the Rock Lake Mound above the summer resort (S.W. 14-3-13). A communication from the Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology is not clear on what was removed from this mound, it lists only a hammer as coming from Rock Lake; but there is a good possibility that some of the specimens in the Royal Ontario Museum, listed as coming from the Pilot Mound district, were from the Rock Lake Mound, as the village of Pilot Mound would likely be Dr. Montgomery's headquarters when in the Rock Lake district. While most of these mounds have had partial interference, the writer is of the opinion it was not extensive, and a rich harvest may yet await the trained archaeologist.

During the month of August 1943 the writer, together with some members of the Manitoba Museum Association, made a partial excavation of the most westerly of the Rock Lake mounds (S.W. 29-3-14). This was named the McLaren Mound after P. L. McLaren the owner of the farm. Several days of careful work through the heart of the mound revealed two bundle burials, one of a child about six years old, and the other of an adult person. Only fragmentary portions of the skulls were present; indeed, the skeletal remains were discouraging to the physical anthropologist. There were not any artifacts associated with the child burial. With the adult burial the following were found: a gorget of red catlinite (in form of a hatchet), a tube pipe of soapstone, a whetstone of some abrasive material, a polished disc with a number of faint notches at one edge, two crude knives, a snubnosed scraper (straight flake) and a broken projectile point. This mound is circular and measures about 55 ft. in diameter. The burials and artifacts were at a depth of 4 ft. 4 ins. below the upper surface of the mound, and appear to have been laid on the original ground level; it was constructed of black earth with a few stones. Almost directly above the burials, and close to the centre of the mound, a heavy post had stood; this was burned and charcoal was found throughout the entire depth. Birch bark was present, but the partial excavation did not reveal any pottery.

One hundred yards south of the McLaren Mound lie the McLaren Earthworks. These run in a southerly direction with a total length of 608 ft. They range in width from 19 to 35 ft. and in height from 2 to 4 ft. Test excavation at the south end of these earthworks revealed further human burials ruinously disturbed by badger burrowing. This end of the earthworks is apparently built mainly of camp rubbish; charcoal, shell and flint flakes are plentiful. There were a few grit tempered potsherds, and two fine artifacts, a knife and an arrow point, both of chalcedony.

At the east end of Rock Lake, there are two mounds known as the Cavers founds (S.W. 13-3-13), named after Mr. Douglas Cavers, owner of the property.

These mounds have both been slightly disturbed, but have yielded one interesting specimen. This is a complete miniature pot which was thrown out of one of these mounds by badger activity and recovered by Mr. Cavers about fifty years ago. This pottery vessel is now in the writer's collection. It is 3.1 inches high and about 3.3 inches at its greatest width. Dull buff in color it has an out, flaring rim with cord impressions on top and geometric incised lines oil the body of the pot. Of the other mounds in the area, the Olson and Odell Mounds await detailed examination. The seventh mound known as the Crayston Mound (S.E. 20-3-13) was examined by the writer during the autumn of 1941. Excavation through the middle revealed a cremated burial, some tube pipe fragments, a few artifacts and two pottery shards similar to those from the McLaren Earth works and the Avery Village Site discussed later.

The presence of these mounds postulates the close proximity of camp or village sites. This phase of archaeological research in the area, however, presents difficulties, due to the rough and often wooded terrain. Three sites (not plotted on our map) should receive careful investigation. One on the N.E. 33-3-13, discovered by Mr. Frank Brown of Glenora, and receiving surface examination only, does not hold much promise of being connected with the builders of the mounds. A second site located by A. E. Macklin of Glenora on the N.E. 24-3-14 may prove more interesting. It is less than half a mile from the Olson Mound; but the material recovered to date is too limited to furnish a basis for opinion. A third site holds equal promise, located on the S.H. 30-3-13 it is also close to the Olson Mound. Examination of material in the Macklin Collection, recovered by surface collection only, indicates some similarity in scraper and projectile types to those from the mounds and to those from the village site discussed in the next paragraph. There is also some material that looks confusing. The answer may lie in the fact that the site is on the same ground as an old buffalo pound, built of logs, and still partly visible in the early 1880's. This pound was likely the work of recent hunting peoples, and the possibility of a double occupation is evident. [2] Nothing indicating camp or village life has been found close to the most impressive of the Rock Lake tumuli, the McLaren Mound and Earthworks.

The most important recent discovery covering this Rock Lake Mound Building culture, is the location on a level table above the Avery Hotel, and below the Rock Lake Mound (S.W. 14-3-13) of an extensive village site. Several hundred pottery fragments excavated during the autumn of 1944 would seem to indicate it is one of the village sites occupied by the people who built the mounds. These fragments compare with potsherds recovered from the mounds and earthworks, and with the complete vessel mentioned above. All are grit tempered with geometric designs predominating, with simple cord impressions or straight incised lines furnishing the decoration. The range of other artifacts found on this site is quite extensive and similar to the limited number found in the mounds and earthworks. They include finely-worked snub-nosed scrapers, all made from flakes with secondary work on one side only. The arrow points are notched and triangular, the bone tools include large fleshers, awls and two broken harpoons. Several side scrapers, small knives and flake knives have been found, all of which reveal delicate secondary work. With one exception the larger knives are either triangular or oval and crude, the excepted specimen is a long curved blade of great beauty. In all of these smaller artifacts chalcedony predominates as the material employed. The larger artifacts include one ungrooved hand axe, several pebble hammerstones and one flat chipped quartzite stone that may have been used for a digging tool or hoe. One pastime is suggested by a cut and drilled bone, likely used in the cup-and-pin game; and ornamentation by the presence of mica fragments and bone beads. Excavations up to date have been limited but thorough; the material reveals an interesting cross-section of a fairly complex culture; and when we add to the above described material, arrow points of native copper and obsidian, we get an outline of an archaeological picture, which challenges considerable anthropological speculation. In concluding this portion of our remarks, it should be added that the mound pottery described by Montgomery (deep spiral groove from midbase to rim) has, so far, not been found.

In the northwest portion of the area, a few miles southwest of the village of Hilton, a second series of mounds is located. These are larger than the Rock Lake Mounds and contain multiple burials with the skeletal material complete. The most important of these mounds is the Sykes Mound (S.W. 15-6-16). It is located on a high hill locally known as Medicine Hill, Signal Hill, etc.; but we have preferred to name it the Sykes Mound, in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Sykes, the owners, whose consent to excavation was always readily given. This mound was partly excavated in 1933 and again in 1943 by a party from the Manitoba Museum Association. In addition to the skeletal material mentioned above, the excavation recovered a triangular projectile point, bone beads, a bone object that could have been used as a pottery marker or was perhaps part of a bone bangle, circular shell necklets and shell pendants. The pendants are similar to those illustrated by Montgomery as coming from the Westbourne Mound (see Montgomery 1908). Copper was apparently used by this prehistoric group, as copper stains are present on some of the bone, although artifacts or ornaments of copper have not been found. So far as the writer can learn pottery of any kind is absent.

Two miles west of the Sykes Mound is the McKay Mound. This was opened by the late Dr. D. A. Stewart of the Ninette Sanitorium, and has been visited by members of the Manitoba Museum Association. The skeletal material and artifacts removed are similar to those from the Sykes Mound. Between the two main tumuli there are a number of smaller mounds so far untouched. We know very little about the people who built the Hilton Mounds. Culturally they appear to have differed from the Rock Lake people. They leave the impression of having been much more artistic. That they were a highly organized group seems evident from the amount of labor involved in building the Sykes and McKay mounds, on the very crest of some of the highest elevations in the Tiger Hill country.

The most impressive of all the sites in the Rock and Pelican Lake area, is the Lowton Site on the S.W. 26-5-16. It is named in honor of Mr. Harry C. Lowton the owner of the farm, and was discovered by Mr. Frank Brown of Glenora who formerly lived in the Belmont district. The site covers an area of about 20 acres and, with the exception of some small groves of poplar, has been under cultivation for about three decades. During that time Frank Brown and other collectors have found several thousand artifacts of various types and a similar quantity of pottery fragments. The artifacts, particularly the projectile points and knives, display a high standard of workmanship. The pottery is almost equally distinguished.

The pottery is grit-tempered and ranges in color from a very dark grey, almost black, to a light buff. The bodies of the pots appear to have been roughened with coarse grass or a paddle. Some rims are plain, but the majority are decorated with cord or incised impressions. Outflaring rims are not numerous and there is some interior decoration. Immediately below the rim on many specimens there occurs a wide variety of cord impressions. Most of this decoration is geometric; two examples, however, in the writers collection have a rainbow cord design quite similar to historic Hidatsa pottery. One example shows an interior slip, two other specimens an attempt at crude effigies.

The majority of the projectile points are straight along the base, notched, triangular in form; and in most cases appear to have been ground along the base. A small percentage are leaf shaped, notched, with a base similar to the pre dominating type. A third type is mainly leaf shaped in outline, notched, with a concave, almost scroll-like, base. These latter points are beautiful examples of Stone Age workmanship. Less than two percent of all the projectile points from the site are un-notched triangular points. Snub-nosed scrapers are plentiful, some of them are flakes with secondary work on one side only, others have been flaked on both the upper and lower surface. Knives are present in a wide variety of types and show equal variation in quality of workship. The oval, triangular and long narrow knives of chalcedony are excellent examples. Drills and graving tools are also present. The material used in the production of the smaller artifacts is rich and varied in color; it covers almost the complete range of suitable stone, and includes obsidian. The bow and arrow was apparently the chief weapon used in securing food and in war; authentic lance points are rare, and the majority of the arrow points, though broad at the base, are small.

The larger artifacts include grooved hammers many of them quite small, pebble hammer stones, one ungrooved hand axe, four stone hoes and a pick-like tool found a short distance from the site but presumed to be part of the village site remains. Bone tools are scarce, only two authentic specimens have been found, one an awl found by Mr. Lowton and now in the Ninette Sanitorium, the other in the writer's collection appears to be the broken end of a gouge, shaped flesher. The inhabitants smoked, but only fragments of what appear to have been tubular pipes have been found; most of these are made of catlinite. Clam-shell fragments are scattered over the site, and one complete clam-shell scraper was found by the writer in May 1944. Another piece of carved clam, shell could have been used as a pottery marker. Further work in shell is found in a small shell ornament with incised lines representing a tree, in a circular disc of marine shell now in the Manitoba Museum, and in a partly broken circular gorget of marine shell, similar to the one illustrated by Montgomery as coming from a mound near Sourisford. There is not any trace of habitations; they are presumed to have been of a perishable nature; and fortifications of any kind arc apparently absent. The site is littered with broken bone, and flakes and chips of flint are plentiful. Burial sites of any kind have not been observed anywhere in the close vicinity.

The ceramic horizon in our prehistoric story does not carry us very far back through the centuries. Six to eight hundred years would appear to be the limit of time involved. The presence of birch bark in most of the mounds is sufficient in itself to exclude any great antiquity. This leaves a vast period of time with little, if any, archaeological material on which to base even a surmised reconstruction. Antevs places the beginning of the Post-Glacial epoch in this area at about 9,000 years ago. Doubtless sometime during the succeeding millennium ancient hunting people entered the district. Two Yuma-like points, another resembling the Brown's Valley type, still others showing evidence of weathering, suggest considerable age, but the data are meagre; and until further proof is found, it would seem safe to assume that any occupancy of the area by ancient hunters was occasional and perhaps not of long duration.

Conclusions of any kind may prove unsafe so early in the unfolding of an archaeological picture. It would seem reasonable to assume however, that the Rock Lake and Hilton Mounds, the Lowton and Avery Village Sites are prehistoric. The lack of white contact material, and the failure of early travelers like La Verendrye to mention any occupancy of the area, when he passed so close in the autumn of 1738, both fortify the assumption. The suggestion that the mounds were built by a Siouan people should receive consideration. Well-known American anthropologists like Swanton, Stirling, Bushnell and others have demonstrated that at least some of the Ohio Mounds were probably built by Siouan people, and suggest the possibility of the dispersal of the Siouan people out of the Ohio Valley, to the south and east; and to the north and west, carrying this cultural trait to far distant areas.

The writer suggests a Woodland affiliation for the Lowton site, its isolated location, cord-marked, grit-tempered pottery, paucity of bone tools and shell artifacts, prompting the speculation. Wintemberg placed the Belmont pottery (Lowton Site) under a Mandan classification (see Wintemberg 1942). This writer doubts the validity of this position, and is inclined to believe that the cord impressed pottery of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Lowton Site people were all derived from Woodland aspects in the east. The Hilton Mounds remain a mystery. The closest mound is four miles from the Lowton Site, this would appear to exclude any connection; yet their shell artifacts seem to indicate a Woodland background. In our opinion the Rock Lake pottery is also Woodland. It is almost identical. with Red River pottery from north of Winnipeg (Lockport), and appears to be part of Wilford's Red River aspect (see Wilford 1941 and Fewkes 1937). The answer to many of the problems surrounding our potterymaking, village-living, mound-building people will be found in the south and east, and comparison with known archaeological horizons south of the international boundary, is clearly needed.

The speculation made in Figure 1, that our prehistoric sites were abandoned for climatic reasons, has always, in the opinion of the writer, been a more reasonable assumption than to suppose that whole tribes were exterminated by war. The dates given are from a tree-ring record covering the State of Nebraska by Harry E. Weakly, climatic similarity in the great plains region being assumed. The Rock Lake and Hilton Mound people must have been highly organized groups. The building of mounds and earthworks with primitive tools demands organized government of some kind, it required the help of many hands either by compulsion or cooperation. The burial mounds, and the various traits revealed, indicate a deep religious outlook, with perhaps a complex ritual and intricate ceremonialism. There is nothing to indicate the method of transportation; it was before the day of the horse and if the dog played any part in their life we have still to discover it. Types of habitation can only be guessed at. They were probably made of perishable material, and traces of earth lodges, though diligently searched for, have not been found. The animal food of these prehistoric people is evident from the vast quantity of broken bone found on all the sites, and ranges from the bison to smaller animals and birds and fish at the Avery Site.

Artifacts found on all the sites suggest a well developed skin-working industry; if other material was used for clothing and shelter careful examination might reveal it. Careful excavation is required to establish what vegetable products, if any, were consumed. The presence of stone hoes at the Lowton Site, and a mano and metate at the Avery Site, suggest digging, gathering, grinding and perhaps a limited agriculture. Clark Wissler has said, "In the New World it was observed that the geographical distributions of agriculture and pottery were fairly coincident". How this rule applies to our Rock and Pelican Lake sites is only one of the many intriguing problems awaiting solution. The deep impression is left that these mounds and pottery-laden sites represent the frontier struggle, the fading trace, of a culturally important people who, as they moved into the northern plains, were forced to become nomadic bison hunters and to forget the traditions and customs of a richer past.

Antevs, Ernst 1931. Late-Glacial Correlation and Ice Recession in Manitoba. Mem. 168, Geo. Sur. Dept. Mines Ottawa.

Bryce, George 1904. Among the Mound Builders' Remains. Trans. 66, The Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba.

Bushnell, David L, Jr. 1934. Tribal Migrations East of the Mississippi. Smithsonian Misc. Coll. Vol. 89, No. 12.

Bushnell, David L, Jr. 1940. Virginia before Jamestown, Smithsonian Misc. Coll. Vol. 100, pp. 125-158.

Coues, Elliott 1897. New Light on the Early History of the Great Northwest. Henry-Thompson Journals. 3 Vols. New York, Francis P. Harper.

Doughty, Arthur G. and Martin, Chester 1929. The Kelsey Papers. The Public Archives of Canada, Ottawa.

Fewkes, Vladimir J. 1937. Aboriginal Potsherds from Red River Manitoba. American Antiquity Vol. 3, No. 2.

Haxo, Henry E. 1941. The Journal of La Verendrye 1738-39. Translated and annotated. North Dakota Historical Quarterly Vol. 8, No. 4.

Jenness, Diamond 1934. Indians of Canada. National Museum of Canada Ottawa.

Montgomery, Henry 1908. Prehistoric Man in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Amer. Anth. Vol. 10, No. 1.

Roberts, Frank, H. H. Jr. 1938. The Folsom Problem in American Archaeology. Smithsonian Rep. 1938, pp. 531-546.

Roberts, Frank, H. H. Jr. 1940. Developments in the Problem of the North American Paleo-Indian. Smithsonian Misc. Coll. 100, pp. 51-116.

Strong, Wm. Duncan 1940. From History to Prehistory in the Northern Great Plains. Smithsonian Misc. Coll. Vol. 100, pp. 353-394.

Swanton, John R. 1923. New Light on the Early History of the Siouan Peoples. Journ. Wash. Acad. Sci. Vol. 13, No. 3.

Wedel, Waldo R. 1938. The Direct Historical Approach in Pawnee Archaeology. Smithsonian Misc. Coll. Vol. 97, No. 7.

Wedel, Waldo R. 1940. Cultural Sequence in the Central Great Plains. Smithsonian Misc. Coll. Vol. 100, pp. 291-352.

Wedel, Waldo R. 1941. Environment and Native Subsistence Economies in the Central Great Plains. Smithsonian Misc. Coll. Vol. 101. No. 3.

Wilford, L. A. 1941. A Tentative Classification of the Prehistoric Cultures of Minnesota. American Antiquity, Vol. 6, No. 3.

Will, George F. and Spinden, H. J. 1906. The Mandans. Peabody Mus. Amer. Arch. and Ethnol., Harvard Univ.; Pap. Vol. 3, No. 4.

Wintemberg, W. J. 1942. The Geographical Distribution of Aboriginal Pottery in Canada. American Antiquity, Vol. 8, No. 2.

Wissler, Clark. An Introduction to Social Anthropology. Henry Holt & Co.

Wissler, Clark. The American Indian. 3rd. ed. Oxford University Press.

Wormington, H. M. 1944. Ancient Man in North America, The Colorado Mus. of Nat. His. Denver, Col.

1 Henry's Rib-bone Lakes, or Lacs du Placotte, sometimes corrupted to Ribbon or even Riband, were the names applied to Rock, Pelican and Swan Lakes by the fur traders in the early years of the nineteenth century.

2 Claude Crayston, a well-known farmer of the Glenora district, furnished the writer with data covering the buffalo pound. Mr. Crayston recalls seeing traces of it in his early youth, and his father, the late Joseph C. Crayston, frequently described the pound.

* Since this paper was read the Manitoba Government has granted funds to the Historical Society which are being devoted to archaeological work.

Page revised: 22 May 2010