MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1959-60 Season

|

Although the 49th parallel had long been named as the boundary line between the territories of Britain and the United States, from the Lake of the Woods to the summit of the Rocky Mountains, [1] no marker had been placed on any spot on its vast extent until Major Stephen Long was sent by the American government to find and mark the 49th parallel at the Red River.

Major Long and his party arrived at Pembina on August 5, 1823. They borrowed a skin tent which they pitched on the river bank near Mr. Nolan's house. A number of tent flies were put up near this, a flag staff was erected, and the place was named Camp Monroe in honour of the President of the United States.

A series of observations was made over a period of four days. Then the distance to the 49th was measured off and an oak post was driven into the west bank of the Red River. The American flag was raised and a salute was fired. This took place on August 8, 1823.

Thus the boundary at the Red River was first located but, in 1870, a new survey revealed that a proper and complete survey of the boundary was long overdue. The following letters tell something of the story of why and how it was begun. The first was written to the Secretary of the Treasury, Washington, D.C.

Customs House, Pembina, June 23, 1870.

Sir:

I have the honor to call your attention to the fact that the United States Military commission under Major-General Sykes, United States Army and Captain Heap, United States Corps of Engineers, while here this spring for the purpose of locating the new fort and military reservation, have made, by a series of careful solar and lunar observations, located and established the 49th parallel on the International boundary line upwards of 600 feet north of the old established post ... This change brings the Hudson Bay Company's trading post north of here within our lines on United States territory, which in case the last established location shall be recognized as the actual boundary line, would subject the whole of the said Hudson Bay Company's stock of goods on hand at said trading post and all future importations thereto to payment of duty. I therefore ordered a full inventory of all their goods and effects for the purpose of assessment of duty in case the said established line shall be recognized as the true boundary.

I would therefor, in view of these facts, respectfully request instructions in the premises, and beg to be advised as to which of the two different lines established I am to recognize as the true boundary line for customs revenue purposes.

I am. J.C.S.,

Collector.

In the reply he received, the zealous collector was advised to do nothing to disturb the existing conditions until a joint action of the two governments could be decided upon.

In a short time the problem was being discussed at a higher level of government. In August, the British Minister at Washington, Sir Edward Thornton, advised his government as follows:

Newburyport,

August 1st, 1870.My Lord

Some days ago, Mr. Fish [2] spoke to me in regard to the boundary line dividing the U.S.A. from that part of the British territory which now forms the new province of Manitoba. He said that Captain Sykes of the United States Army had lately made a careful survey of the line and discovered that it was really much to the north of where it was supposed to be; so much so that the Hudson Bay Company post near Pembina, which was supposed to be in British territory was actually in that of the United States.

As this state of affairs might hereafter lead to serious disputes, Mr. Fish thought that it would be advisable at some future time to appoint a mixed commission who would survey the line on the 49th parallel, and should mark the actual boundary. In the meantime he suggested that the government of Canada should appoint some person who might verify the observations taken by Captain Sykes, so that there might be no danger of a misunderstanding in the interval, and until the boundary might be authoritatively decided and marked.

I deemed it right to submit these remarks of Mr. Fish to Sir John Young [3] in a confidential dispatch, a copy of which I have the honor to enclose, so that his Excellency may cause such enquiries to be made as he may deem expedient.

I have the honor to be, with the highest respect, my Lord,

Your Lordship's most obedient, humble servant,

Edward Thornton.

In the following month, Adams G. Archibald, the Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba, in a letter to the Canadian government, expressed his views of the state of affairs at Pembina.

Fort Garry,

September 29, 1870.Sir:

In my dispatch No. 6 under the date of 27th instant, I had the honor to advise you that in anticipation of possible interference with the flat boats coming down the Red river with supplies of goods for this place, Colonel Jarvis, at my request, has dispatched a company of 1st Ontario Rifles to the Hudson Bay Post at Pembina.

I am glad to be able to report that many of the boats laden with goods have since come down in safety, and that I have good reason to believe the stationing of troops there has been very useful as a check against anticipated attacks.

The troops are at present encamped about half a mile this side of the Hudson Bay post at Pembina.

It seems that about the year 1850 the present general, then Captain Pope, under authority from the United States government, took observations to fix the exact spot where the 49th parallel crossed the Red river, and after spending several days in this service, erected a post on the bank of the river to mark the spot. This post is about a quarter of a mile to the south of the Hudson Bay company fort, and is still standing.

Sometime about 1860 the people of Pembina erected another post on the river bank about a mile from the first post. A man from this settlement [Fort Garry or Pembina] had put up a house close to the boundary line and was carrying on a trade in whiskey which was smuggled into the village of Pembina, and this post was put up and the local authorities claimed jurisdiction to it so as to drive the party away. This has been locally known as the "Whiskey Post", but beside its local object had no significance.

Last spring a corps of American engineers were sent out by the American government to lay off a military reservation in the neighborhood of the boundary line and a series of observations was made to fix the parallel. Eventually they put up a post which is about half way between the original post and the Whiskey post, but at such a point as to throw the Hudson Bay post into the American territory. I have no means of knowing whether they had any authority from their own government to run out the parallel Neither have I any means of knowing whether, when Captain Pope put up his post, he did so by joint authority, but whether or not, the same having been put up by United States authorities, it would seem to be admission of the boundary line, particularly when coupled with possession by us, and continuous recognition by both parties from 1850 to 1870, that it could not be disturbed except by mutual consent. At all events, no one party could have the right to establish a new line without the consent of the other and for all national purposes the original line must, I presume, be assumed to be the correct line, till changed by mutual consent.

Be this as it may, I have felt it my duty to report the facts as they were stated to me for the information of his Excellency, the Governor-General and for such action as lie may see fit to take.

(signed) Adams G. Archibald.

These various letters brought results, and after much correspondence, an arrangement was made to set up a joint commission to mark the boundary from the northwest point of the Lake of the Woods to the summit of the Rocky Mountains.

Canada at this time requested that Captain D. R. Cameron, son-in-law of Hon. Charles Tupper, be named Commissioner, and that the Secretary, Chief Astronomer and two assistant astronomers be sent from Britain. Actually forty-four men were sent.

The personnel of the commission was chosen as follows: Commissioner, Captain D. R. Cameron, R.A.; Secretary, Captain A. C. Ward, R.E.; Chief Astronomer, Captain S. Anderson, R.E.; with assistants Captain Featherstonehaugh, R.E. and Lt. Galway, R.E. Surveyors: Col. Forest, of the Canadian Militia, Mr. Russell and Mr. Ashe. A number of sappers from the Royal Engineers were trained in various trades which included: wheelwrights, blacksmiths, tailors, carpenters, shoemakers, four photographers and a taxidermist. Captain Herchmer was made commissary and arranged for great quantities of food, clothing, blankets, hardware, horses, wagons and building materials from Montreal, Toronto, Windsor, St. Paul, Breckonridge and Winnipeg to be got ready. A photographic outfit was packed by the Engineers School at Chatham, England; a library was selected which had a wide variety of books as well as games and stationery; woollen underclothing, saddlery, meat extracts and dried compressed vegetables were purchased in Britain; instruments were borrowed from the Admiralty and other good instruments were obtained; and tenders were invited to supply the iron markers which would be the final markers on the boundary. Professor G. M. Dawson was chosen as geologist and botanist, and the commission was rounded out by obtaining the services of Doctors Burgess and Millman, and veterinarian Boswell.

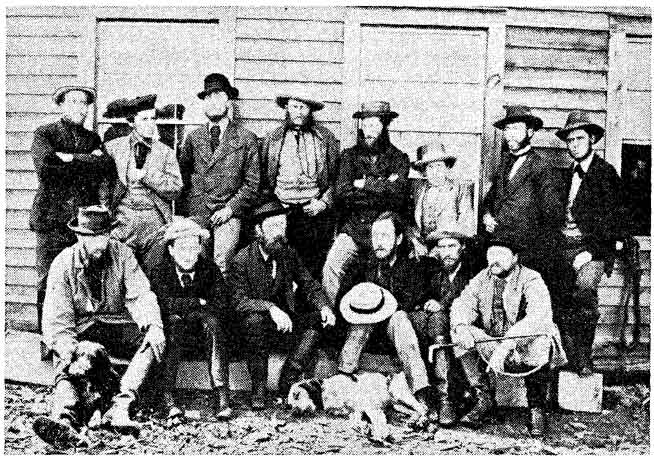

Officers of the British Commission

Standing, l. to r., Assistant Astronomers G. Burpee, W. F. King, G. Coster; Commissary, Capt. L. Herchmer; Capt. S. Anderson, R.E.; Prof. G. M. Dawson; Astronomer Ashe; Surveyor, L. Russell.

Seated, l. to r., Lieut. Galwey, R.E.; Capt. A. C. Ward; Commissioner Capt. D. R. Cameron, R.A.; Capt. Feathersionehough; Veterinary, Dr. Burgess; Surgeon. Dr. G. Boswell.

Finally, the men were warned that they might expect to be asked to perform many tasks which would ordinarily be outside the line of duty, and above all, they were never to show the least sign of contempt for the Indians, but must at all times welcome them into the camps and if asked, to state plainly the work they had been sent to do.

Captains Cameron and Ward left England in advance of the main party so that they could confer with the American commission, but were first informed that early maps indicated that the meridian from the north west point of the Lake of the Woods seemed to cut off a piece of land, leaving it in American territory. This land should be retained by Canada if possible.

The main party left England on August 11, 1872 under the command of Captain Anderson. The chief bulk of supplies came with them. At Quebec the party changed steamers to go to Toronto, at which place they took the train to Collingwood and travelled from there to Duluth by steamer. With the permission of the American government the party travelled up the St. Louis River - then by train to Moorehead. Here they were joined by the Commissioner and Secretary and the whole party marched to Frog Point by way of the old coach road. At Frog Point they embarked upon the steamer Dakota to travel to their final destination. September 20 found them camped just north of the Hudson's Bay Co. post of North Pembina. This place was described as consisting of a palisaded Hudson's Bay Co. fort, a log building used as the Canada Customs House and four or five log cabins.

Before winter set in, the commission moved into their permanent quarters located two miles down the river. This place was enlarged during the winter and was named Dufferin in honour of the Governor General of Canada.

The very first task was to take astronomical observations for latitude to determine the exact whereabouts of the 49th parallel at Red River. This work was hindered by a severe equinoctial storm which lasted two days and blanketed the country with several inches of snow.

It was found that the Hudson's Bay post was in Canadian territory, but the Canada Customs House stood just across the line. Strangely enough, this building was used by the Canada Customs for several years after this discovery was made.

Commissioner Cameron with Astronomer Anderson, and U.S.A. Commissioner Archibald Campbell with Astronomer, Major W. Twining travelled to the Northwest Angle to search for the Reference Monument. This monument had been erected by Dr. I. Tiarks in 1825, when Mr. Barclay was the British Commissioner. The monument was described by David Thompson as being a square crib of logs eight feet square at the bottom, tapering towards the top, and situated on dry land.

When this party reached the Northwest Angle it searched for days but could find no trace of the monument. Finally, Mr. James McKay arrived from Fort Garry and took two Indians with him to find the site. These Indians remembered old men of the tribe telling of the monument. When found, the site showed the imprint of the logs quite clearly, but was under eighteen Inches of water; the lake being unusually high. It was 210 feet from the newly surveyed spot. On October 18, a meridian was laid off by members of the two commissions.

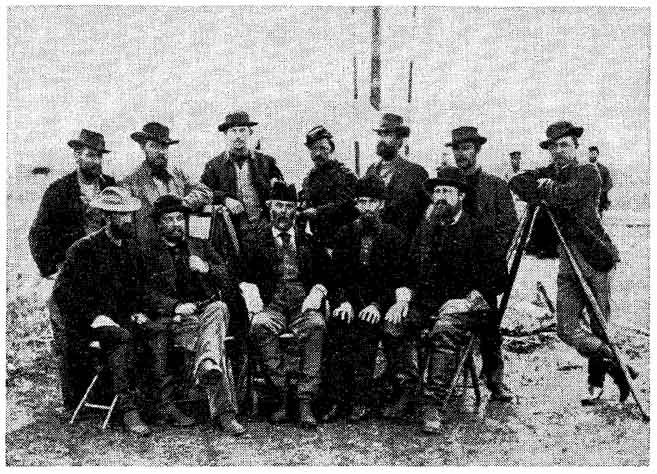

Officers of the American Commission

Standing, L to R, Mr. Bangs, secretary; Major W. Twining; Lieut. Green, surveyor.

Seated, L to R, Capt. Gregory, astronomer; Col. F. M. Farqueher, chief astronomer; Archibald Campbell, Commissioner. The six men at the right were escort officers.

Captain Cameron had been told to hold off signing any agreement, but he did consent to having the meridian surveyed and a vista cut. This line was sixteen miles long. It was found that the steamer landing, and that a half mile of the Dawson Road actually were in American territory.

The work on this small piece of land and between the Lake of the Woods and Red River was very difficult. Much of the land was swamp, and the men never knew when they would break through the thin crust of vegetation and be up to their armpits in slimy muck. Once into this, it was hard to climb out again. Besides this, the underbrush and fallen timber made travel with ordinary vehicles impossible, so man-packing of supplies and instruments was not unusual. When the frost set in, the footing was better but travel was still difficult. In a short time, however, supply depots were established and trails were opened between the camps.

The winter of 1872-73 was very severe. It was so cold that the astronomers complained that the instruments became so chilled that their accuracy was effected, and that they had to be taken apart and every trace of lubricating oil removed. Even then, they made the eyes of the men water so that they had trouble with their vision. Captain Anderson overcame this problem by having a small tent erected within calling distance of the observation tent, in which a small stove was kept burning so that the instruments and men could be kept warm.

Major Twining reported that in one part of the swamp he found that the September storm had put such a covering of snow on top of the rushes and reeds that the water underneath did not freeze at all, though it was icy cold. After getting a team of mules into it, and finding it very hard to get them out again, he had special sleighs made which could be pulled by a single animal. Then he sent men on snowshoes to make a road by tramping the snow into the water, where it instantly froze. The road thus made was not very safe, for every snow storm filled up the tracks, and if a load slipped off, or a man lost his footing, several hours were required to right the load or there was delay while clothing was changed.

In January, 1873, a very bad three-day storm occurred. Tales of a stagecoach full of passengers, and children on their way from school being frozen to death proved to be only too true. The same storm found two men of the commission on the prairie east of the Red River. They cut the horses loose, wrapped themselves up in all the blankets and robes they had and, lying in the bottom of their sleigh, waited out the storm safely. In March, the men were told to ask for lengths of green gauze to protect their eyes from snow blindness, because part of the swamp was a great expanse of glare ice.

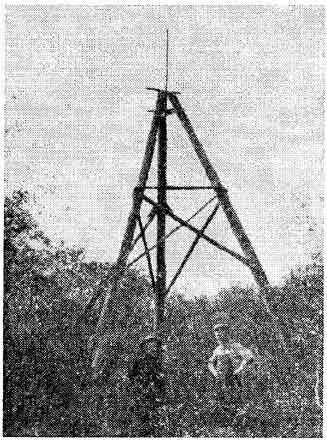

Old tripod at the head of the Northwest Angle inlet erected by the Boundary Survey of 1872-76. Photo taken in 1912.

All winter the work went on; the astronomical parties taking observations, the surveyors chaining and staking the line, the axe-men cutting the thirty-foot vista and the slow ox teams and faster dog teams constantly on the move with supplies.

The Spring of 1873 found them with all the surveying done and the line carefully marked with posts from the Northwest Angle of the Lake of the Woods to the Red River. The permanent iron posts were to be placed later. The parties all returned to Dufferin just before the spring thaw.

Now the work started west of Red River, and here the two parties worked together. The system was that the British would set up an observation station where they would shoot the stars for several nights, the Americans would set up a station twenty miles further on to do likewise, so that the parties were always passing one another and were never far apart. The surveyors then connected the stations and surveyed a strip of land six miles wide on each side of the line.

In order to save valuable time, Captain Cameron asked to be allowed to hire a corps of scouts, and this request was granted. These men were mostly metis from Pembina, and were a valuable asset to the force. They were given the work of riding in advance of the work parties to find good camp and depot sites; these sites were chosen with a view to adequate supplies of wood and water and were at suitable distances apart. The metis were to find and mark the best places to travel and were to report any unusual features. They were to report on the presence and on the friendliness or unfriendliness of any parties of Indians they might encounter, and were to try to make friends of them. They were to hunt for game when meat was required, and they were to keep the parties in touch with one another and with the headquarters. This last seemed particularly important as the distance to the headquarters became greater and the stories of hostile Indians grew more frequent. Notes in the Manitoba Free Press at that time blamed the stories of hostile Indians on the Hudson's Bay Company.

The scouts with one or two officers made five reconnaissance trips and campsites were established and depots built. An important depot was Wood End, at the third crossing of the Souris River, and, as the name implied was at the end of the wooded country. The second main supply depot was near Wood Mountain and from here arrangements were made to bring supplies, especially oats for the horses, from Helena, Montana.

The greatest hardship for the men in this land west of the Red River was the alkaline water. This made the men sick. In the Turtle Mountains there were so many stagnant pools that some of the men, who were engaged to do the cutting through the woods, were invalided.

The Summer of 1873 saw 408 miles of boundary surveyed and marked with posts or cairns of stone or mounds of earth, the vistas cut through the Pembina and Turtle Mountains and depots built. Oats were stored and hay was put up and stacked in carefully burned-over spots, as prairie fires were a fearful menace.

The parties started the field work in May of 1874 in the far west and here they met with a whole new set of problems. The telegraph book of Lieutenant-Governor Morris gives us an idea of some of these:

May 26, 1874. Whitford, Trader, cousin of Mr. James McKay, arrived. Reliable man. He reports Americans at Bow river again made a number of Assiniboines drunk February last and killed 55. He had wintered at the south branch and learned from persons present that Sioux chiefs had assembled Metis at Woody mountain to consult as to the propriety of stopping boundary survey. Metis refused to interfere, but Sioux in large numbers had crossed the Missouri to be ready to stop the commission if their chiefs decided to. He thinks both statements true. Think a confidential messenger should go in advance of Boundary commission and also of the police force to explain their objects. If authorized can send a reliable man and Sioux interpreter and believe may avert trouble. A. Morris, Government House, Fort Garry.

Another telegram reads:

June 22, Dufferin, to Lt./Gov. Morris: It is reported by Charles Grant, Point Michele, Pembina river, that Indians have assembled one hundred miles west of Wood Mountain settlement to stop Boundary survey until government has declared a satisfactory policy. D. R. Cameron, H.M. Commissioner.

A note after these messages states that five men with ten carts were sent with an agent in advance of the commission and the police.

Meanwhile, the work of the commission went on, but the men were advised to stay fairly close together-no one was to stray away from the parties at work, as the country was almost unknown and the Indians could be hostile.

West of Wood Mountain, a large herd of buffalo was encountered, with a very large encampment of metis following them. Captain Anderson backtracked on their trail and found the settlement of metis of which he had heard but which few white men had visited. The settlement was composed of about eighty families which had come originally from St. Joseph. They would not allow any of their members to act as scouts for the commission, but the men from Pembina were able to do the work even in the far west.

West of Wood Mountain, near the village of Val Marie, Saskatchewan, a large tract of land had been owned by the Montana Ranch Company. Early in the present century, the Winnipeg meat packing company of Gordon, Ironsides and Fares bought part of this ranch. This ranch had been partly stocked with Texas Longhorn cattle which had been driven up the famous Chisholm Trail. After the purchase by the Canadian company more of these cattle were brought up by train to this ranch.

At the Sweet Grass Hills rattlesnakes were seen for the only time and at one spot the battered bodies of twenty dead Crow Indians were found. They had supposedly been on a horse-stealing foray but had been discovered.

On August 18, after arduous climbing and much searching, the advance party discovered the monument on the summit of the Rocky Mountains. This had been erected by an earlier commission which marked the line from the west coast to the summit of the Rockies.

This last bit of surveying was very difficult because of the rugged terrain. One small piece could not be chained as it was so nearly perpendicular. But the work was remarkably well done and for the first time the boundary between United States and Canada was completely marked.

On August 29, Captain Anderson and his party started on the long trip back to headquarters at Dufferin. As he moved eastward, he was joined by all the other parties. The trip was made in forty-three days and covered 860 miles. The iron monuments were hauled during this season ready for a small party to install the next year.

From the beginning, life was not dull at headquarters. During the first winter, the men increased the capacity of the barracks and stables, and there was a constant going and coming of men and teams. The saloons of the frontier town of Pembina were patronized enough to cause the medical officer to list delerium tremens as one of the prevailing ailments. On April 1, 1873, one of the sappers was coming home, late and inebriated, from the town when his musket accidentally discharged. The result was that the man lost the sight of one eye. On another occasion, when the enlisted men were evidently returning to Dufferin from Pembina, they got into such a heated argument that finally the American militia was called out to quell the disturbance. Arrangement had been made with the Americans that their militia would come to the aid of the British enlisted men if hostile Indians threatened them seriously, but to subdue them on this occasion was a duty they did not expect. On one New Year's day, notices were posted to the effect that two men were fined a day's pay for being unfit for duty. Whiskey at seventy-five cents a bottle was no deterrent.

A strange thing was that, although there was a very large amount of medical supplies including several tents and one marquee, field kits to meet almost any emergency, teamsters and several ambulances, there was no hospital at Dufferin. Sick and well lived together. Fortunately no epidemic occurred.

The following letter tells the story of a man who was sent by Captain Cameron to go to Fort Garry to bring back $15,000 from the Receiver-General, Mr. Gilbert McMicken.

Dufferin, Manitoba,

December 21st.To: The Secretary of Her Majesty's N.A.B. Commission.

Sir: I have the honor to submit to your notice my statement of the case of a deficiency, to the amount of forty dollars, which was found in the sum of fifteen thousand dollars carried by me from Fort Garry to Dufferin, Manitoba. I went to Fort Garry on Sunday the Twenty fourth of November last year, at the request of the commissioner, to fetch the sum of fifeen thousand dollars from the office of Mr. McMicken, receiver general of that place. On the evening of the same day, I went to Mr. McMicken's private residence and handed him a note given me by the secretary, in which were the documents which were necessary for my obtaining the money.

Mr. McMicken promised to have the money ready for me early next morning as there was immediate necessity for it at Dufferin, and the stage was supposed to start at daylight or soon after. I presented myself next morning at an early hour and found that the clerk had not finished counting all the money, but that a good part of it was ready for me to count. The notes were of several denominations. I counted the one dollars and the twenty-five cent scripts and found the amount of each correct, when seeing that it was getting late, the clerk kindly consented to tell out to me the balance of the money, note by note, to save the time lost by my slowness in counting, and to enable me to catch the stage. He had told out some of the other notes - when I settled that it would be best to trust the amount being correct and to catch the stage which had already waited beyond its time of starting with all its passengers on board.

My reason for so concluding was this: Captain Cameron had desired me to make as much haste as possible, and to endeavor not to let it be known that I had such a large sum of money in my possession. To miss the stage was to lose two days, and I could not safely retain the money in my own keeping for that time in a place like Fort Garry where it was impossible to get a room to myself in an hotel.

Consequently it would have been necessary to count it all over again, at the same hour and under the same circumstances two days later. Besides this, attention would have been drawn, by my repeated visits, to the fact that I was taking money from Mr. McMicken's.

The clerk then put the notes into a satchel which I had brought. A number of the notes were in sealed packets, just as they had been received from one of the banks, the rest were simply tied in bundles with a string.

I hung the satchel round my neck with a strap and did not remove it, even at meal times, till I reached the Hudson Bay fort, where I went to tell the commissioner that the money had arrived.

After walking to Dufferin, I saw the satchel opened and the money counted. Four ten dollar notes were wanting out of the unsealed bundles. I did not unlock the satchel from the time I was in Mr. McMicken's office until I handed it over to the Secretary at Dufferin.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant, Geo. Coster.

The loss was not charged to Mr. Coster.

All the while work was going on in the west, it was also continuing in the vicinity of the Angle. As has been stated, Cameron was informed that the meridian from the Northwest Point seemed to cut off a piece of territory which should belong to Canada. Now the British Foreign Office decided to try to negotiate with the American government for the land. The opinion of the British government was that the American government should renounce all claim to it, as a matter of convenience to both countries, but that if she would not do this, Canada should state what sum she would be willing to pay for it.

Before making an offer, Canada wanted a full report on the worth of the area. Accordingly, an intensive study was made under the headings of mineral, timber, agricultural and fishing wealth. Every ridge and stream was traversed with painstaking care. The report, when it came, stated that the land itself was of little value, being mostly swamp and rock, but that its strategic value was great, having on it the landing stage. Accordingly, the Canadian government informed Lord Dufferin that she would be willing to pay $25,000. dollars for the land. This was by an Order-in-Council passed November 27, 1874.

Sir Edward Thornton was ordered to sound out Mr. Hamilton Fish, to see if an agreement could be reached. Thornton's first proposal was that America cede the land to Canada, with or without payment. This would cause the boundary to follow the Rainy River to its mouth, then follow around the south shore of the Lake of the Woods to its intersection with the 49th.

The second proposal was more complicated in that the maps made under the earlier commissions did not agree, one showing the boundary to be the mid-channel of the inlet which formed the Northwest Point of the Lake of the Woods, and the other the mid-water line, the difference between them meaning that Canada might, under the one, retain the landing stage but, under the other, she would not be able to do so. In searching the old maps and records, Captain Cameron could find no positive and final signed agreement in either case, so thought this a good basis for negotiation.

But the report of Sir Edward indicated that Mr. Fish showed great dislike for any proposal whatever that would entail the loss of any land. Mr. Fish said that he had consulted the President and cabinet on the matter and they were not in favour of making the change, "as they were sure the American people would not support the loss of even a small piece of land; this is a matter upon which the Americans are very touchy."

The matter was aggravated by the complications of dealing with three governments, and by the fact that the telegraph line at Pembina was sometimes out of use because of storms and prairie fires. At one time, Cameron had been told to sign an agreement, later, an order came telling him to hold off a little longer, but he had already obeyed the first order. So nothing at all was accomplished by all the careful examination of the land at the Angle or by the searching out of old records.

That was not the end, however, for now Captain Anderson was asked to report on the feasibility of constructing a canal from the Lake of the Woods to the mouth of the Roseau River, the purpose of which was to establish an all-Canadian water route from Lake Superior, through the Lake of the Woods, down the Roseau and Red Rivers, up Lake Winnipeg and up the Saskatchewan River for freight vessels. Some work had previously been done on the Lake Superior part of this route.

To find a course for this canal, Professor G. M. Dawson was sent to explore the old canoe route which had been the war road of the Sioux and Chippewa Indians, but had seldom been used by white men.

This route began with the Reed River, which was about ten miles from the 49th. This river runs westerly for about fifteen miles. The next stage was the portage through swamp - nearly eight miles long and worn into a rut by the canoes having been pulled through it then by the East Roseau River into Lake Roseau, then by the West Roseau to its mouth.

Since the Roseau crossed the boundary, and since the whole distance surveyed was 160 miles long, a shorter, more direct route was thought advisable. This would start just north of the boundary in Buffalo Bay and the first section would extend to the East Roseau, a distance of some seventeen miles with a fall of ten feet to be overcome by a lock. The second section would be from the East Roseau to Pine River, with the East Roseau to flow through a culvert under the canal. The third section, to be formed partly by embankment and partly by excavation, was a stretch from the Pine River to the Roseau River at Point d'Orme - a distance of twenty-six miles. The last part would follow the Roseau from this last crossing of the 49th to the Red River and the work would be mostly widening, with locks and dams.

The canal was to be made of wood and was to be thirty feet wide. But, after all the surveying and estimating was done, Captain Anderson gave his opinion that to find a new site for a landing at the Angle, with a new piece of road leading from it to the main part of the Dawson Road would be the most economical thing to do, but with the ultimate aim of building a railroad far to the north. This last solution would provide comfortable travel all year round and would be safer and more easily defended in case of hostilities with the United States, while the canal would be of use for only a few months each year.

At this point, the only remaining work was to find a spot to build a new landing stage, and although Mr. Fish was quoted as saying that Canada should be prepared to make great concessions if she wanted the piece of land in question because there was no other place a landing could be built, he was proved to be wrong. A poplar ridge north of the original stage was found to be suitable. A road was built which first lead north, then west, then south to join the old road.

With all the surveying and exploring done, there remained only the permanent markers to be placed. This was done in the summer of 1875 by a small party of workmen. Most of the men were dispersed, while the officers worked at their reports. A large amount of supplies were left and these were taken over by the newly-formed Mounted Police.

On March 18, 1875, Cameron wired the British government that the Canadian government wanted to buy the property at Dufferin. He was advised to sell at a price set by a competent valuer.

On May 5, 1876, the British government received a bill of exchange for £27,478, 16s, ld, in payment for the Canadian share of the cost of the commission.

This ended nearly four years of costly and gruelling work, which Dr. Coues of the American Commission neatly sums up in the following quotation from his book containing the Journals of Alex. Henry:

Thus it happened that, after more than a century of dispute, arbitration and survey, two nations have in and about the Lake of the Woods that politicogeographical curiosity of a boundary that at a glance at the map will show, that no one could have foreseen, and that would be inexplicable without some knowledge of the steps in the process by which it was brought about. Either nation could better have afforded to let the boundary run around the south shore of the lake from the mouth of the Rainy River to a point where the shore is intersected by the parallel of 49 degrees.

For the sources of information for this paper I wish to acknowledge the help given by the late Dr. Leslie Johnston, the British Society for the Advancement of Science, the Manitoba Archives, the Canadian Archives for microfilming a large part of the reports in the British Foreign Office, the University of Manitoba for allowing a travel grant which made it possible to go to study the microfilms, and I wish to thank Dr. Wm. Morton for his kind advice.

1. The Treaty of Paris (1783) had fixed the northwestern boundary as a line running from the northwest point of the Lake of the Woods to the Mississippi River; the negotiators relying on an old map which showed this stream as originating not far from Hudson Bay. After several fruitless efforts to settle the boundary, the Convention of London in 1818 did give a workable arrangement. This agreement reads: "It is agreed that a line drawn from the northwestern point of the Lake of the Woods, along the 49th parallel, or if the said point shall not be in the 49th parallel of north latitude, then that a line drawn from the said point due north or south as the case may be, until the said line shall intersect the said parallel of north latitude, and from the point of such intersection due west along, and with the said parallel, shall be the line of demarcation between the territories of the United States, and those of His Britannic Majesty, and that the said line shall form the northern boundary of the said territories of the United States, and the southern boundary of the territories of His Britannic Majesty, from the Lake of the Woods to the Stony Mountains."

2. Hamilton Fish. Secretary of State, U.S.A.

3. Sir John Young, Governor-General of Canada.

Page revised: 22 May 2010