MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1944-45 season

|

When the Icelanders began to flock to this continent in the early seventies of the last century, the movement may be referred to as their "second coming", for they did not come as strangers to a foreign shore. They came as a people who knew this land from a long way back because their forbears had found it many centuries before Columbus had explored its eastern shores; had tried to establish homes there; and had returned to it at intervals for several hundred years.

When the Icelanders began to flock to this continent in the early seventies of the last century, the movement may be referred to as their "second coming", for they did not come as strangers to a foreign shore. They came as a people who knew this land from a long way back because their forbears had found it many centuries before Columbus had explored its eastern shores; had tried to establish homes there; and had returned to it at intervals for several hundred years.

Details of these events had been preserved in the sagas and annals of Iceland and were familiar. They date back to the year 1000 A.D., when Leif Erikson [1], a viking born in Iceland, discovered the eastern shores of this continent and wintered on the Atlantic coast. A colony was founded and given the name "Vinland". While this attempt at permanent settlement failed eventually, Icelandic records [2], as well as Vatican manuscripts [3] at Rome, indicate that sporadic attempts at further occupation were made and that voyages from the Icelandic colony in Greenland were continued until well into the fifteenth century.

The second movement of Icelanders to this continent, which resulted in the founding of the first permanent Icelandic settlement on Canadian soil at Gimli, in 1875, began with a trickle as far back as 1856 when a couple of Icelanders left their homeland for Utah, arriving by covered wagon. There is record of a small party heading out for Brazil in 1863. Then in 1870, three young Icelanders passed through Quebec en route for Milwaukee where they formed the nucleus of an Icelandic colony still extant.

It was not until the year 1872 that an Icelandic immigrant entered this country with the idea of becoming a Canadian citizen. He was Sigtryggur Jonasson, a lad of 20 - descendant of one of the powerful families in the saga-age of Iceland. He found himself a job in Ontario, mastered the English language, and when his countrymen began to pour into the country, gave them direction and leadership.

The first families from Iceland reached Ontario in 1873 in a party of one hundred persons. Half of these went on to Wisconsin, but the remainder made a fruitless attempt to found a colony at Russeau, Muskoka.

The lot of these earliest arrivals was by no means a happy one. A still larger group, three hundred and sixty-five in all, which entered Ontario in 1874, found only intermittent and underpaid work at railroad grading, and fared so badly that first winter spent at Kinmount, that all babies under two died.

This party had originally intended to settle in the United States, but were persuaded by an agent of the Dominion government to give Canada a try-out under promise of special privileges. These were: a grant of sufficient suitable land on which to set up a colony; the same rights as other Canadians as soon as they had complied with residential requirements; and freedom to retain their language, customs and way of life for as long as they wished. Families from this group formed the majority of those who founded the colony at Gimli, while single persons from among them began the Icelandic invasion of Winnipeg.

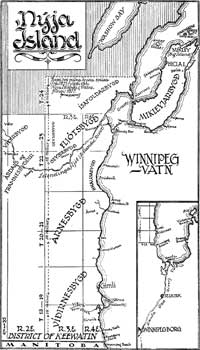

The colony-site, eventually chosen for them by their own representatives, was north of the Manitoba boundary (as it was at that time) and formed a strip along the west shore of Lake Winnipeg, six townships in length and extending 12 miles inland. It also included the whole of Big Island. The area was then part of the Northwest Territories, but later became known as the District of Keewatin. The land was covered with trees and shrubs, with natural clearings and marshes between. It had been selected because it offered building materials, fish and game to augment the food supply, together with a navigable waterway. That it was heavy land to work and offered only subsistence living because of distance from markets, does not seem to have been considered.

The settlers bound for this terrain reached Winnipeg on October 11, 1875. There were two hundred and eighty-five persons in the party-eighty men, one hundred and thirty-six women and sixty-nine children. These were the people who founded the first permanent Icelandic colony on Canadian soil. Their colony has another distinction which gives it a unique place in the pioneer history of Manitoba, in that it governed itself in all respects after the manner of a republic during the first twelve years of its existence.

Thirty-five single persons from the party remained in Winnipeg to find work and were the first Icelanders to take up residence in this city. The rest stayed only long enough to purchase supplies from the Hudson's Bay Company, and to load them on the house-boats on which they were traveling down the Red River and Lake Winnipeg to their destination.

The fact that they had credit with which to buy, they owed to the intervention of two men - John Taylor, an Easterner interested in their fortunes, and Lord Dufferin, the governor-general who had visited Iceland and liked its people. When Taylor failed to convince Ministers of the Crown that it was sound economy to help the Icelanders to get their colony started, His Excellency came to the rescue with a measure of success. Taylor was then appointed by the Government to accompany the colonists as their business agent.

The party was composed almost entirely of young people. The supplies they took to the colony included their personal belongings, boxes of books, quite a bit of scrap metal, a modest store of food, cooking utensils, tools, seed, and twine for nets. Livestock, for which they had saved the bulk of their credit, would have to wait until spring owing to the lateness of the season. In fact, when they reached the tarn on the south side of Gimli Harbor on the "last day of summer," winter was setting in with a vengeance.

There was no time to spread out on their farms as first intended. The men went ashore, felled trees and built thirty cabins within three weeks to house most of the party. Also a log warehouse to hold the extra supplies. A few families settled on farms in the immediate neighborhood.

The colonists called their new village "Gimli," and their settlement "New Iceland." The winter was severe, the houses over-crowded; there was sickness but there was also good hope and cheerfulness. Almost at once a committee of five was chosen to supervise the distribution of supplies and to look after welfare matters such as, health, sanitation, and fire hazards.

Here the first Icelandic newspaper in Canada was produced in longhand - five issues being circulated. Its name - if it had one- is forgotten.

In the spring the settlers spread north over the district and built their houses on farms, mostly along the waterfront; spaded up the soil to put in gardens; brought in a number of cows and oxen; and started the fishing operations which were to expand and grow into one of Manitoba's great commercial enterprises. The late summer brought them the first of many parties of new settlers, eleven hundred persons who were helped to locate on farms.

The year's end brought disaster. An epidemic of smallpox swept the community, leaving one hundred and two persons dead by spring - mostly children and young people. Many were so disheartened that they wanted to abandon the settlement, and eventually a good many of them did. Isolated they had indeed been for six months, behind an armed barrier set up on their southern boundary. When the quarantine was finally lifted, it was July and too late to put in seed. The outlook was not hopeful.

Help came in the way of employment, for at this time, the Federal government voted money to survey a road through the colony together with $8,000.00 to carry out the work. Most of this was done by the settlers at sixty to seventy cents per day plus their keep. The same rate of pay was accorded a number of the women who were employed in looking after the camps.

All supplies for the community had to be brought in by water in flatboats and small row boats. This included staple goods for a store opened that summer, the first in the settlement, whose proprietor was Fridjon Fridrickson. The first lumber arrived.

That same fall (1877) brought a personal visit from the Governor-General. whose interest and friendliness did much to restore the courage and ambition of the settlers. Plans were completed for the publication of a newspaper and for the institution of municipal government.

The first issue of the newspaper appeared September 10, 1877, in Icelandic. It was called Framfari [4] (Progress) and was financed by the sale of stock at $10 a share. Printed in a hand press at Riverton, it appeared twice a month, and was sometimes carted around to the various districts by a runner on skates.

In workmanship, material carried, and general appearance, the Framfari is remarkably fine and compares favorably with contemporary issues of the Manitoba Free Press. Primarily it served the settlers in all official matters, such as publishing the municipal bylaws under which they were to carry on; keeping the colonists informed of public meetings, the trend of discussions, and the decisions reached. Local events were covered. It carried informative articles on a variety of subjects - some translated, but many original, together with world events and Canadian news, devoting considerable space to Federal Government action - especially where it affected the West.

Altogether thirty-eight issues of the Framfari appeared, the last on April 10, 1880. The venture then failed because of financial difficulties.

With their newspaper established the colonists turned their minds to the constitution under which to operate their colony. Since they were in unorganized territory, and pretty much on their own, they felt that the constitution needed to cover all phases of public administration. To carry any authority it should have the sanction of all concerned.

Two public meetings had been held early in the year (1877), one at Riverton, the other at Gimli. Each meeting chose a committee of five men to draw up a set of by-laws, the committees to act independently, and when both had their drafts ready, to meet together and consolidate these into one set of regulations to form a constitution.

The constitution, which came into effect when it appeared in the Framfari, January 14, 1878, made the colony virtually a republic. It regulated elections; defined the duties of voters as well as officials; provided for taxation and public works; for relief to the needy, guardianship of minors, appraisal and disposal of-estates; arbitration of disputes with a court of appeal; the keeping of records, covering vital statistics, economic progress, estates and wardships.

Matters of general policy which affected the whole had to be referred back to the electors, while within the framework of the constitution, individual districts had full autonomy in affairs which affected only themselves.

The constitution consists of eighteen articles, many of which have several subsections. The first Article divided the colony into four primary electoral districts, each of which was to elect annually an executive committee of five, to have charge of local matters and together with similar committees from the other districts to form a Governing Council for the whole colony. The set-up thus seems to have been four municipalities united under a grand-council made up of all their joint executive officers.

The overall Council elected a chairman and vice-chairman from among their own number. Elections were for one year only, the districts going to the polls on January 7, each year and the Council meeting within one week there from.

All men over eighteen years of age who were farmers, property owners, or regularly employed and who had nothing against their character, were on the voters lists. All who were over 21, except ministers and school teachers, were eligible for office.

Article five, under seven sub-headings, defines the duties of electors. They must attend a rate-payer's meeting between March 15 and April 15, each year at the call of their District chairman to discuss matters of interest and concern to their own community; each elector over twenty-one was required to contribute two days' work a year to roadmaking, or else pay two dollars; each head of a household had to give notice of births and deaths within a week, and bridegrooms were to report marriages; each householder was supplied with a special form on which to itemize his holdings and economic progress each year; they also had to provide relief to the needy, and pay a tax of twenty-five cents a year to the district chairman.

The District Committees had charge of road making and upkeep in their own area; appointed trustees of estates and guardians, and saw to it that these made a strict accounting; provided widows with capable advisors and such other aid as needed; safeguarded public health, and were authorized to take any measures necessary to stop the spreading of disease; and finally it was their duty to stimulate civic consciousness, sociability, cooperation and ambition in their electorate. Besides all this, they were members of the Council for the whole.

The District Secretaries must have been especially hard-worked. They had to keep a set of five books - one for minutes, one for census figures and economic returns; one for road work and attendant accounts; one for vital statistics: and one for all records pertaining to valuation of estates and the sale of them, together with trusteeships and guardianships. All municipal records had to be displayed for inspection at annual meetings.

A fee was set for valuating estates, and if the heirs were outside the colony, these had to be wound up within a year.

Two important officials elected each year were the Arbitrator and Peacemaker. When their mediation failed to settle a dispute, a judiciary committee of five citizens was set up, two named by each side, in addition to a chairman - if they could agree on one - if not the Reeve or Vice-Reeve presided. The findings of this judiciary committee were final.

Article 11 deals with the constitution of the over-all Council, whose executive was composed of a Reeve or chairman and the four district chairmen. If no candidate for Reeve got a clear majority in the elections, no new Reeve was elected - the old one carried on for another year.

The Council discussed and dealt with all welfare matters affecting the whole - such as getting the area of the colony extended; admitting to it persons of other nationalities, and the promoting of new enterprises.

The final article provides for amendments to the constitution. Amendments had first to be approved by the overall Council, then a referendum on them was taken in all the districts, with all of them voting on the same day.

While the constitution nowhere defines what shall be considered a quorum, it stipulates in a number of instances that findings shall only be valid if more than half of those entitled to vote are present. This ruling affected all elections and changes in the constitution.

Sigtryggur Jonasson was elected first Reeve of the colony. It carried on under this system of government for twelve years, managing all its own affairs, administrative, social and economic.

Examination of the eighteen articles of government shows two notable omissions in the ground they cover, the first, no provision for punishment - either for failure to comply with the regulations or for the breaking of the natural laws of man - with the exception of the negative one of withholding the right to vote. Thus, for orderly conduct the colonists appear to have counted on their unity of interests and their dependence on one another together with common sense and the ten commandments, rather than regimentation.

The second omission was in making no provision for education. Schools were already in operation at the time the laws were framed and obviously the districts were expected to do as they had been doing - establish their own schools and distribute the cost among those who used them. [5]

It seems strange that they continued to administer the colony under this constitution until 188'7, when actually, as early as 1881, the extension of Manitoba northward had taken in their territory. But the answer probably lies in the fact that the Manitoba Municipalities Act of 1881 recognized already existing municipal governments in the new area as legal authorities. It wasn't until after the amendment of the Municipalities Act in 1886 that the Gimli colony brought itself into line with practice elsewhere. Thereafter, district executive committees were replaced by single councillors, the schools came under the regulation of the Manitoba Education Act, and taxation ceased to be on a voluntary basis.

Of the colony's many early needs, perhaps the greatest of all was money, particularly money for livestock - cows and oxen - for seed and tools and agricultural implements to work with.

To meet this need, all young people, and some of the farmers themselves, were compelled to go outside the colony to hunt work. They went in groups, on foot, all the way to Winnipeg where the men might get railroad work or hire out at casual labor at the prevailing rate of one dollar per day. The women found housework mainly, at $4 to $6 per month. Most of this pay was saved and sent to their families for necessities. Sawmills had begun to operate on the east shore of Lake Winnipeg and a number of men found work at logging. Others cut cordwood and logs on their own land - for poor returns because of the distance from market. These forays to bring in the needed capital retarded progress in the colony where every pair of hands was needed for the many tasks.

But the colonists were thrifty, hardworking and resourceful; regardless of the effort it cost, everything which could be made at home, wholly or in part, was made there.

They made their own early nets; bound them with twine, weighted them with kidney-shaped stones hunted up on the beach, and gave them buoyancy with floats shaped from thick bark.

All boats, complete with oars and oarlocks or sails, were built in the colony. For the earliest ones, the lumber was sawn by hand, and bent into shape by a long-drawn-out process of immersion in hot water.

The pioneer log houses were constructed and furnished out of the materials at hand. The style was not Red River frame, but one of the Icelanders' own pattern, each wall retaining the unbroken length of the logs used, the corners tightly morticed. Lime for plaster and whitewash was obtained by burning limestone in homemade kilns, the stones being dragged or carried from the beach.

When the first oxen came into use, harness was not bought complete but only leather and buckles. After the leather was cut, a homemade vise, held between the knees, kept it in place, leaving the hands free to do the heavy stitching.

The wooden parts of most of the tools and implements were made by the settlers, and only the metal parts bought. This included carpenters' benches and lathes, spinning wheels, plows and harrows as well as mallets, picks, axes, hammers, shovels, planes and other tools.

Many additional articles were contrived entirely from local materials - a quern or grinder for grain was made with granite stones on a wooden foundation. It looked like a large doughnut sitting on top of another that hadn't had the piece taken out of the centre. Tubs and vats, barrows and sleds, skis, skates and snowshoes, hayricks and hand rakes were among the things so constructed.

No fencing was bought. The woods and a lot of hard work provided rails and posts, as well as willow withes to bind them with. Drainage ditches, laboriously dug, had no culverts and had a heartbreaking habit of closing in after heavy rains. Everything which had to be transported anywhere, was at first carried on the backs of men, and later by rowboat or behind patiently plodding oxen.

The women shared in much of this toil when time from other duties permitted. All food was prepared in the home, and what was in excess of the day's requirements, preserved. Fish was cleaned and scaled, then salted, dry-cured, smoked or even pickled. Milk, after the colony's cows multiplied, was turned into butter, cheese, skyr, and the residuary "whey" stored, which served as a preservative for pickling. When an animal was butchered, the Icelandic housewife drew on her inherited knowledge and made many tasty and vitamin-filled dishes from parts of the animal now often allowed to go to waste.

In her spare time the housewife spun wool and knitted all undergarments. socks, mitts, shawls and scarves for her family. This took considerable doing for a man lifting nets through the winter ice, required several pairs of mitts a day, not to mention socks. She made waders from calf-skins; also shoes, the latter of light weight, well-worked skins for the women and children, and heavier leather ones for the men.

From the beginning, education was a major consideration, with emphasis on English. Icelanders, then as now, believed that education was the finest thing in preparation for life that they could give their children. They realized that without knowledge - particularly knowledge of English - they would be badly handicapped both in gaining for themselves what Canada had to offer, and in giving Canada her dues as citizens.

All children were taught at home to read and write Icelandic. All were more or less familiar with the Icelandic Sagas, poetry and, folklore. Every home had its treasure of books, and one pioneer alone donated one hundred volumes from his collection when a public library was established.

The first school began operation with the colony itself that first winter in Gimli. Children and grown persons, both men and women attended, with Miss Susie Taylor, niece of John Taylor, as the first teacher. An early issue of the Framfari refers to the Gimli School being full to capacity with forty children in attendance. That was pretty fair attendance for any "little red school house" of the pioneer West. Another item, this from Big Island, refers to securing a teacher for three months - "a pleasant and tactful man", who received nine dollars a month and board for a class of twenty children. The school varied from three to six months and covered the wintertime only. All four districts had their schools.

When the settlement was four years old a statistical survey, published in the Framfari by the council, placed the total population at 1,029 persons with families numbering 234. These were living in 214 houses - almost one family to each domicile. It may be assumed that the "doubling up" by twenty families was due to newcomers from Iceland who were being sheltered until they, in turn, had been helped to build.

Two-thirds of the houses, or 157, had cellars, and half of them had wells. Eighty-two miles of fences had been built and ditches dug for drainage; 882 acres of bush and brush land had been cleared, and 432 acres were under cultivation. There were forty-five miles of roads - other than the main highway. Ninety-four bushels of wheat sown in 1879 yielded about seven bushels to the acre. This was one-quarter of the colony's requirements.

Emphasis laid on livestock had brought results as the community owned 476 cows - a little over two per family - also 130 oxen for freighting and plowing, 611 young cattle of various ages, as well as a number of pigs and chickens.

The colonists had built 129 boats ranging from fishing scows to modest sailboats. Another year was to introduce a steamer. The report goes into further details on fishing equipment and the number and types of fish caught.

Comment by the reeve, who compiled the report from the records of farmers from all districts, reveals that the report does not include the many persons temporarily away from the colony; nor houses, lands and work, whose original owners had left for other parts; at Arnes alone, thirty-one of the original homesteads stood abandoned.

When the first survey of Manitoba fisheries was made in the nineties, Icelanders were found fishing on all the larger Manitoba lakes and they still constituted about seventy-five per cent of the industry. Two attempts made by the New Iceland colony in the early days to establish canneries in order to eliminate the cost of freighting, were a failure. Before the settlement was thrown open to other Nationals in 1895, colonists owned steamers for freighting, had freezers at various points on the lake and shipped their winter catch by organized freight caravans. Profits were, however, cut in half by the cost of the long haul to market.

Each year brought fresh parties of immigrants who were helped to locate, or tided over until they could go in search of their fortunes somewhere else. The economic strain on the colony from this retarded progress, yet most of the original pioneers stayed on. They had started on the job of making a successful colony and held to the faith that it could be accomplished. Out of those who went off, some swelled the population of early Winnipeg and smaller towns; others pushed westward into unsettled country to carve out homes and found new colonies. As a result, by 1890 Icelanders had opened up the wheat country around Argyle in south-western Manitoba, the mixed farming communities on both sides of Lake Manitoba, and by 1900 had their colonies at eleven different provincial centres.

Little mention has been made of the growth of the Icelandic colony in Winnipeg. Its early struggles parallel those of the Gimli settlement. The Winnipeg Icelanders, too, extended hospitality and help to thousands of their countrymen. In fact, they found that burden so heavy that on April 26, 1886, they called a public meeting to urge the Federal Government to assume the burden of providing work for Icelandic immigrants.

Early in the city's history they took a vigorous interest in civic affairs and after a time elected their own aldermen to the City Council. Their first news, paper, the Leifur, appeared in May, 1883, and circulated until June '86; the two Icelandic weeklies which still are published in Winnipeg were started shortly afterwards. By 1900 the City had an Icelandic population of four thousand. It has long been the social and intellectual centre of Icelandic culture on this continent.

Seventy years have passed since the coming of the first Icelanders to this province. The pioneers who founded that first colony - who stayed with the job and saw it through - have passed on. But the work they did for this country in their day, goes far beyond the boundaries of the grant of land in which they strove and toiled. Up to the end of the century the majority of the thousands of immigrants who streamed out of Iceland, headed straight for the Gimli settlement where they were welcomed, housed, fed and guided. If they chose to remain, they were helped to locate and build, and assisted in a variety of ways to ensure a successful living. If, and when, they left for other places promising quicker returns, they took with them something of the spirit and determination of the pioneer founders, as well as something of their substance.

During all the early years this pioneer colony carried on the duties of a colonization and immigration department - shouldering the expense and the worries; a responsibility which was eventually recognized as belonging to the Canadian government.

So many Icelandic colonies mushroomed out in Manitoba and elsewhere in the West that in time the "New Iceland" district became known as "The Mother of Icelandic Settlements."

The Manitoba pioneers had realized their own dream of founding and sustaining a free Icelandic colony in the New World. They had also made good the dream of Leif's followers to establish permanent homes on the continent discovered so many centuries ago.

On their record the Icelandic people will always rank among the West's important pioneers, for they opened up many of the virgin lands on the prairies where they still have large and prosperous farm communities. They have been thrifty, resourceful, law abiding and loyal citizens, and have spilled their blood freely in two wars for Canada - not as Icelanders but as the good, honest Canadian citizens which they are.

The story of the Icelandic pioneers is one of a people facing squarely up to hardships and difficulties and taking advantage with courage, of such opportunities as offered. In this respect their trials and achievements have perhaps been duplicated by other settlers in other places; but the shining page which they wrote in Manitoba history with their twelve year demonstration of democratic self-government, has no parallel.

The soundness of their philosophy and way of life is indicated by Margaret McWilIiams in her Manitoba Milestones, on page 158, where she says: "They of all the people who have come to Manitoba, have most quickly become identified with the British population and have made the most progress in the general life of the province."

1 Saga of Erik the Red whose source material is found in the Flateyjarbok manuscript written in Iceland in 1387 on parchment, and now in the Royal Library at Copenhagen.

2 Hauksbok (1299) which tells of the "Vinland" voyages and of Thorfinn Karsefni, his wife Gudrun and their infant son, Snorri, the first white child born in the New World. The Hauksbok parchment is preserved in the "Arna-Magnaean" (Arni Magnusson) collection in the University of Copenhagen library.

3 Papal letters discovered in Vatican archives in 1902, being instructions from various Popes to Archbishops of Norway in whose see the Greenland - New World Christian communities were included. These letters begin with one from Pope Innocent III, in 1206 and continue with long intervals to the end of the fifteenth century. Copies of these letters are in the Museum of the University of St. Louis.

Pages from all three above sources have been reproduced in facsimile by the Norroena Society London, Stockholm, Copenhagen, New York) with English translations, under the caption "Pre Columbian Historical Treasures, 1000-1492.

4 The Framfari is now in the Provincial Library in the Manitoba Legislative Buildings.

5 Full text of the constitution and governmental regulations will be found at the end of this paper.

6 Published in Framfari, Vol. 1, No. 6, December 22nd, 1877, pp. 22-23. Lundi, Keewatin.

A brief sketch of the circumstances connected with the drafting of this constitution, etc., is found ibid, No. 5, December 10th, 1877, p. 18, col. 3 - Translator.

7 This must be a misprint; the year is 1878 - Translator.

8 Published in Framfari, Vol. 1, No. 8, January 14, 1878, pp. 3132 Lundi, Keewatin. (Lundi near Riverton) - Translator.

9 i.e. Icelandic River, on which Riverton is situated - Translator.

10 Balloting limited to such persons (cf. Section XI, Article 2) - Translator.

11 Evidently the Dominion Government - Translator

12 "Sandy Bay", near which Sandy Bar is situated - Translator.

Agreements in Reference to a Temporary Constitution in New Iceland [6]. Translated by Professor Skuli Johnson.

Article 1 - The land-claim of New Iceland shall be called the Lake Region, and shall be divided into four Districts which are called: The Settlement of Vidirnes, the Settlement of Arnes, the Settlement of the River, and the Settlement of Big Island.

Article 2 - The inhabitants of each District shall at a public meeting on the second working-day in January elect five individuals for a committee; those who receive the most votes are duly elected members of Committee, but only if there are present not fewer than a full half of those who are eligible to vote. If anyone asks to be excused from election, he who has obtained votes next to members of the Committee is duly elected; the same rule shall be followed if some member of Committee becomes incapacitated, or resigns from the Committee. If individuals obtain an equal number of votes, age decides. This Committee has under its jurisdiction all such matters as affect the district itself.

Article 3 - Every District-Committee shall elect a Chairman, who is called District-Governor, and a District Vice-Governor, who shall attend to the duties of the District-Governor when he is incapacitated. The other duties which devolve on it, the Committee may apportion among its members in such a manner as the Committee deems best suited.

Article 4 - The Right of Election and of Voting all have who possess permanent abodes in the Settlement, and are 21 years of age, and have an unblemished reputation.

Article 5 - Elections are valid only for one year but the same individuals may be re-elected.

Article 6 - The first working-day in March the inhabitants of every District shall hold for them a public meeting, to discuss all such matters as affect the District; in addition, the District, Governor shall summon men to meetings, as often as the Committee deems it necessary.

Article 7 - Every farmer is obliged to send to the District-Governor a clear account of all his economic condition before the end of November annually, in accordance with a form prepared for the purpose; furthermore, to notify him of the deaths that happen at his home, not later than 6 days after the date of death.

Article 8 - Committee-men of each District shall have care of road-making and of road-improvements, each in its District, similarly, of affairs of the Poor, in accordance with the regulations pertaining thereto that are established in each District; moreover, they shall make an inventory of the Estates of deceased persons, and evaluate them not later than 20 days after the date of death; they shall hold auctions and see to it that widows have efficient counselors, and orphans reliable trustees. The latter shall annually render to the District-Governor a clear account of their stewardship.

Article 9 - The District-Governor of each district shall deal with those matters especially that now shall be detailed: (a) to summon Committee-men to meetings, whenever he deems it necessary, and to conduct them; furthermore, to keep a regular record of what is transacted at the meetings. (b) to enter all public accounts in a special book. (c) to decide on each occasion who are to make an inventory of Estates of deceased persons, and to apportion those that are to be divided, as soon as possible within the next twelve months. (d) to conduct all auctions or to entrust them to others. (e) to attend all meetings of the Regional Council and to communicate its decisions to the inhabitants of his District.

Article 10 - For making an inventory of an Estate of a deceased person and for evaluating it, 5% should be paid; for an auction, 5%; for apportioning an Estate, 5%; of each of these up to a value of $500. From $500 to $1,000, 3% from $1,000 and thereover, 2%. For writing materials and for writing, the District-Governor is entitled to 5 dollars per year; and for necessary books, payment in accordance with an account, to be made out of public funds.

Article 11 - All District-Committee members shall, at a joint meeting to be held at Sandy Bar, seven days after they themselves are elected, elect a person to be called Governor of Regional Council, and shall, together with the other four District-Governors form a Council which is to be called Regional Council. To the position of governor of Regional Council may be elected only that Icelander who is well-versed in English, and who is domiciled in the Settlement. If he has previously been elected to a District Committee he must resign from that post. A Vice-Governor of Regional Council shall also be chosen to attend to the duties of the Governor of the Regional Council when he is incapacitated. The election of the Regional Governor is valid for the same period as the Committee-members, but he may be re-elected. If he asks to be excused from election or becomes incapacitated to serve, the same rules shall be followed as are established in Article 2, concerning members of District-Committees.

Article 12 - The Regional Council shall annually have a meeting for itself the next working-day after the election of the Regional Governor, and, in addition as often as he deems necessary, at the place that he on each occasion determines.

Article 13-The Governor of the Regional Council shall deal with duties that now shall be detailed: (a) to summon to all meetings of the Regional Council and to conduct them, and to keep a regular record of all that is transacted at the meetings. (b) to present all matters that need to go to the Superior Government, and to communicate to the District-Governor all its Ordinances, and, in general, to be a connecting-link between them and the government in all respects. (c) to manage all accounts that pertain to the inhabitants of the Region, and to enter them in a book which he is to have with him at all meetings of the Regional Council, for the District-Governors to see, and also to publish them in print. (d) moreover, to notify District-Governors of such matters as need to be discussed at the District-meetings.

Article 14 - If members of the District-Committees are at variance concerning some matters that affect the Districts, the Regional Council shall settle their contentions or shall put the matter to arbitration.

Article 15 - Majority of votes shall decide the conclusions of cases at all meetings.

Article 16 - The inhabitants of each District shall at each election-meeting elect two men to seek to effect a settlement in all private cases; if this does not succeed, they shall advise the parties to the case to put the matter to arbitration. If no conciliation results, the plaintiff shall pay each of the conciliators $1.50 per day; but if conciliation succeeds, then both parties to the case shall pay in accordance with agreement. Payment is to be made when the attempt at conciliation is completed. Conciliators shall be obliged to record their attempts at conciliation.

Article 17 - These regulations may be altered at a public meeting which the Governor of the Regional Council shall call in accordance with the wishes of a majority of members of District Committees.

Article 18 - These regulations shall be communicated to the public at District-meetings on February 14, 1877, and they shall then obtain legal validity.

Temporary Articles:

Article 1 - For the first time shall an election-meeting be held in each District on the 14th of this month (February).

Article 2 - Until a clergyman arrives, inhabitants of Districts shall give to the District-Governor reports of population before the end of each year; moreover, of births, within a week from the date of birth, each at his own home.

Governmental Regulations of New Iceland [8]. Translated by Professor Skuli Johnson.

Section 1: The Districts of New Iceland

The land-claim of Icelanders in New Iceland is named the Lake Region. It shall be divided into four Districts that are called:

(1) the Settlement of Vidirnes which comprises Townships 18 and 19, Range 3 and 4, East;

(2) the Settlement of Arnes which comprises Townships 20 and 21, Range 3 and 4, East;

(3) the Settlement of the River9, which comprises Townships 22 and 23, Range 3 and 4, East; and

(4) the Settlement of Big Island which comprises all of Big Island.

Section II: The Election of District Committees and of Conciliators

The inhabitants of each Settlement shall, at a public meeting to be held annually on January 7th (but on January 8th, when it happens that the 7th comes on a Sunday) elect a committee of five men called District Committee, two conciliators and one vice-conciliator. They shall be duly elected members of the District Committee who receive the most votes, but only if there is present more than half the number of the dwellers in the District who are eligible to vote in accordance with Section III. If any ask to be excused immediately at the meeting, others shall be elected in their stead, but if any members of the committee are incapacitated subsequent to the election-meetings, in their places shall come those who obtained the most votes next to the committee members. If some receive an equal number of votes for fifth places on the committees, the choice concerning them shall be settled by restricted balloting. [10] The same regulations are valid for the election of conciliators, as are here set out for the election of members of District Committees.

Section III: The Right of Voting. Eligibility for Election

The right of voting at the election of District Committees and of conciliators every man shall have who is eighteen years of age, and is a permanent resident, or who possesses real estate, or who is a householder or has permanent employment in the district, and who has an unblemished reputation. All those who are eligible to vote shall also be eligible for election to District Committees, except those who are incumbent clergymen or permanent public school teachers. Yet however no one is eligible for election who is not twenty-one years of age.

Section IV: The Duties of the Public

Article 1 - Attendance at Meeting - The inhabitants of each District shall attend a public meeting of the District between March 15th and April 15th at the place and date determine, by the District-Governors to discuss matters affecting the public welfare of the Districts.

Article 2 - Road-work and Dues for Roads-Every male who is twenty-one years of age shall be obliged to contribute annually to the construction of public roads, labour of two days of ten hours each, or he shall pay Two Dollars into the Road-Fund of the District in which he is: permanent resident; but those who have no fixed abode shall work or pay where they happen t be when the roadwork is being done. The roadwork shall be done at such place and time as District Committees determine.

Article 3 - Notices of Death, Births and Marriages - Every head of a house shall be obliged to notify his District-Governor of deaths and births that occur at his home within a week after such events take place. Furthermore, every man who marries is obliged to notify his District Governor within the same time.

Article 4 - Reports on Economic Condition and Population - Farmers and householders of every district shall give their District-Governor a clear account annually before the close of December of all his economic condition, also, of the population at his home, in accordance with a form prepared for this purpose.

Article 5 - Support of Widows and Orphans - The inhabitants of every district shall be obliged to support widows and orphans in accordance with such regulations as the majority of the district inhabitants approves; furthermore, those who for special reasons cannot earn for them their livelihood.

Article 6 - The Erection of Meeting-Houses - The inhabitants of every district shall provide themselves with a meeting-house in the manner and at the place that the majority regards as most practical.

Article 7 - Payment to Public Needs - Every inhabitant of each district eligible to vote shall pay annually 25 (twenty-five) cents which is to be lodged in the pertinent District-Fund, and which is to be collected in accordance with the mode determined by the District-Governor; this payment is to be made before the close of September in each year.

Section V: The Election of District-Governor, Treasurer and Secretary

Every District-Committee shall elect from its number a chairman who is called District-Governor, and a Vice District-Governor; the Vice District-Governors are to perform the duties of District Governors when they are incapacitated to serve; furthermore, every District Committee shall choose, also from its number, a Treasurer, and a Secretary.

Section VI: The Duties of District-Committees

Article I - Supervision of Roads-District Committees shall take care of road-making and of road, improvements, each in its own district.

Article 2 - Appointment of Counselors and Trustees - The Committee shall see to it that widows have efficient Counselors and orphans reliable Trustees. Trustees shall annually render an account of their stewardship to the District-Governors.

Article 3 - Concern for the Poor - The Committee shall have care of matters affecting the Poor, in accordance with Section IV, Article 5.

Article 4 - Supervision of the Building of Meeting-Houses - The Committees are to arrange that the inhabitants of each District provide themselves with a meeting-house, in accordance with Section IV, Article 6.

Article 5 - Election of Governor of the Regional Council-All members of Committees of each District shall be obliged to attend meetings to choose a Governor of the Regional Council, and a Vice-Governor of the Regional Council. The election-meeting for this is to be held on the seventh day after the election day of District-Committees, one year at Lundi, the next at Gimli.

Article 6 - Supervision of Health-The Committee shall have supervision of health conditions, each in its district, and shall make special arrangements to prevent the spreading of infectious diseases, when need demands.

Article 7 - Encouragement for Co-operation and Communal Activity - The Committee members of each district shall urge and arouse the inhabitants of their districts to all manner of co-operative and communal activities that aim at the economic welfare and advancement of the district.

Section VII: The Functions of District-Governors, Treasurers and Secretaries

A. Duties of District-Governors

Article 1 - Notices of Meetings - District-Governors shall summon their district inhabitants to the meetings that are mentioned in Section II and Section IV, Article 1, and shall conduct them. Moreover, they shall call additional public meetings when the committees deem there is need.

Article 2 - Committee Meetings - They shall summon their associate committee members to meetings, whenever there is need, and shall conduct the meetings.

Article 3 - Recording of Minutes - They shall see to it that the Secretary enter all transactions of the meetings in a book to be called No. 2.

Article 4 - Recording of Reports on Population and of Economic Conditions- They shall enter reports of population and of all the economic conditions of their district annually in a book to be called No. 2.

Article 5 - Recording of Road-Reports - They shall enter financial statements on road-making and on road-improvements, together with a report on roadwork, annually, in a book to be called No. 3.

Article 6 - Recording of Deaths, Births and Marriages- They shall enter all the deaths, births and marriages that occur in the district of each of them, in a book to be called No. 4.

Article 7 - Recording of Inventories, etc. - They shall enter inventories, evaluations, auctions, partitions of estates, and trustee accounts in a book to be called No. 5.

Article 8 - Attendance at Meetings of the Regional Council - They shall attend all meetings of the Regional Council and take the decisions of such meetings for communication to the inhabitants of their districts.

Article 9 - The Examination of Official Books and the Communication of Reports - They shall have all their official books with them at the annual meetings of the Regional Council, for audit; and they shall send to the chairman of the Regional Council, annually, before January 7th, all reports that are mentioned in Article 4, S and 6 of this Section.

B. Duties of Treasurers

Article 1 - Supervision of District and Road-Payments - The Treasurer shall receive and collect all the money which accrues to the District and Road-Funds, and shall disburse from them in accordance with arrangements of the District-Governor.

Article 2 - Recording of Revenues and Disbursements - He shall make entries in a regular book of Revenues and Disbursements, which the District-Committee shall audit at the termination of each year.

C. Duties of Secretaries

Article 1 - The Recording of Transactions at Meetings - The Secretary shall record all that is transacted at the meetings of the District-Committee and at public District meetings.

Article 2 - The Preparation of Voters' Lists and the Counting of Ballots-He shall prepare Voters' Lists and see to it that they are accurate; he shall receive and count the ballots at all elections in the District and the votes on law-proposals that are submitted to the District inhabitants for their approval.

Section VIII: The Management of Estates of Deceased Persons, and the Dues From Them

Of the Estates of Deceased Persons to which fatherless and motherless minors, and to which persons who are not domiciled in New Iceland have claims of inheritance, the District-Governor shall make an inventory; he shall evaluate them, and sell them at a public auction, if it is necessary, and he shall make an apportioning as soon as possible or within the next twelve months. At the making of the inventory and at the evaluating, the District-Governor shall have with him two member, of the District Committee.

For making the inventory and the evaluation of an Estate of a Deceased Person, payment of 3% must be made; for auctioneering and collecting, 4% for apportioning, 3% of each of these of to a value of $500; but of the value from $500 to $1,000 there shall be paid 2% for the inventory and evaluation; 3% for the auction and the collection; and 2% for the apportioning; but of the value of $1,000 or over, there shall be paid I26/0 for the inventory and evaluation; 2% for auction and the collection; and l ½ % for the apportioning. For all other auctions which District Governors hold, payment must be made in the same proportions.

Section IX: The Duties of Conciliators and Arbitrators

The duty of Conciliators is to seek to compose differences in all private cases. The Conciliators shall summon before them, the parties to the dispute at some definite time and place, in accordance with the wish of either party to the case, and notification by letter shall be a sufficient notice of summons. If conciliation comes to nought the plaintiff shall pay each conciliator 1 (one) dollar for the attempt at a settlement, but if a settlement comes about, then both parties shall pay the same amount according to agreement. Payment is to be made when the attempt at conciliation is completed. Conciliators shall be obliged to record their settlements and their attempts at conciliation.

If the attempt at conciliation does not succeed, or if either of the parties to the case does not attend after a legal notice of summons, then shall the parties, if either so demands, place the case before a board of arbitration of five impartial individuals which the parties to the case themselves select. Each party to the case shall nominate two, but the fifth member shall be the Governor or the Vice-Governor of the Regional Council if they cannot agree on the fifth one. The majority vote of the Committee of arbitration decides the issues. Arbitrators are obliged to record their decisions.

Section X: The Drafting of By-Laws by District Committees

Each District Committee shall draft law-proposals for By-Laws that do not conflict with these constitutional regulations, concerning various matters that affect its district, such as by-laws affecting the affairs of the Poor, by-laws about fences and sureties, and about the handling of all unidentified flocks, etc. It shall place these proposals before eligible voters of the district at a public meeting of the district for their approval; if a majority of all district inhabitants eligible to vote casts its ballots for them, they obtain legal validity.

Section XI: The Regional Council and the Governor of Regional Council

Article 1 - The Formation of the Regional Council - The Lake Region shall be governed by a Committee of five, called the Regional Council. It shall be composed of the District-Governors of the four Settlements of the Region, and of that man who is elected in accordance with Section VI, Article 5, and who shall be called the Governor of the Regional Council.

Article 2 - The Election of the Governor of the Regional Council - Eligibility for the Regional Governorship and the Regional Vice-Governorship every man possesses who is eligible for membership on a District-Committee (see Section III). A duly elected Regional Governor shall be one who has obtained the majority of the votes of all members of District Committees in the Region. If it happens that no one obtains a majority of the votes then restricted ballots shall be cast for the two who obtained the most votes. If neither of them obtains a majority of the votes, then shall the incumbent Governor continue in office until the next election-meeting. If the Governor or the Vice-Governor asks at the meeting to be excused from election, then the balloting shall be repeated. If the one who is elected Regional Governor is a District Governor he shall resign from his District-Governorship before he assumes the Regional Governorship.

Section XII: Meetings of the Regional Council

The Regional Council shall hold one main meeting annually, on March 10th or on March 11th if the 10th is a Sunday. This Council meeting shall be held at Gimli in the years when the election, meeting is at Lundi, but at Lundi in the years when the election-meeting is at Gimli. Moreover, the Regional Governor shall summon the Regional Council to additional meetings when it is necessary to be held at the place and on the day that he on each occasion determines.

Section XIII: The Functions of the Regional Council

Article 1 - The Discussion of Regional Affairs and the Drafting of By-Laws - The Regional Council shall discuss all matters that affect the Region as a whole, and that aim at its advancement in any way, e.g. to obtain an enlargement of the Settlement; to permit native-born individuals to make land-claims therein; to negotiate with persons to set on foot serviceable enter, prizes, etc. The Regional Council shall draft law-proposals concerning such matters, which the District-Governors shall bring forward to be voted on at public meetings, each one in his district. Every law-proposal that obtains a majority of the votes of all the inhabitants in the Region shall obtain the validity of law.

Article 2 - The Supervision of the Main Highway and of Inter-District Roads - It shall have care of the building and the maintenance of the main highway of the Settlement from north to south, and of all roads that run between Districts from east to west; similarly, of necessary bridge building over rivers, brooks, and marshes on these roads.

Article 3 - The Auditing of Books-It shall audit all the official books of the District-Governors and the Account-book of the Regional Governor, and see to it that they are accurately entered.

Article 4 - The Composing of Contentions between Districts - It shall compose cases, if differences arise between any Districts of the Region, or else the matters shall be submitted to arbitration, in the same way as was determined for private cases in Section IX.

Section XIV: The Functions of the Regional Governor

Article 1 - The Summoning of Meetings - The Regional Governor shall summon all meetings of The Regional Council (See Section XII), and shall conduct them.

Article 2 - The Recording of Transactions of Meetings - He shall enter all transactions of meetings in a book called No. 1.

Article 3 - The Recording and the Publication of a Summary of District Reports - He shall enter in a book called No. 2 an abstract of all Reports of District Governors of the Region, and publish the abstracts in print annually.

Article 4 - The Recording of Road-Reports and Accounts - He shall enter in a book called No. 3, reports and accounts of such road-construction as comes under the Regional Council, and produce it at the main meeting of the Regional Council.

Article 5 - The Presentation of Matters to the Superior Government11 - He shall present all such matters as affect the Region and require to go to the Superior Government, and he shall notify District-Governors of all its Ordinances in so far as they concern the Region.

Article 6 - The Directing of District-Governors concerning Diverse Matters - He shall direct District, Governors to the matters that require to be discussed at meetings of District Committees or at public District meetings, in preparation for the meetings of the Regional Council.

Article 7 - Sitting on Committees of Arbitration - He shall sit on Committees of Arbitration in accordance with Section IX. For this service the Regional Governor is entitled to 5 (five) dollars for each occasion.

Article 8 - The Survey of Conditions of the Region - He shall at the election-meeting of the Regional Governor present a clear survey of his activities for the preceding year, and of what has been done, and what affects the Region as a whole; he shall make clear how conditions in the Region stand; he shall explain what its prospects are; and what, in his opinion lies at hand to do regarding public affairs of the Region, and what policy he regards as the right one in that regard.

Section XV: Validity of Elections and of Voting

All elections that are mentioned in these Regulations are valid only for one year, but the same persons may be re-elected. The majority of votes shall decide elections, and also decisions on matters at all meetings which these Regulations contemplate.

Section XVI: Payment for Writing-Materials and Books

For writing-materials and for the books which the Regional Governor, the District-Governors, Treasurers and Secretaries are obliged to keep; similarly, for necessary printing, they are entitled to payment from District-Funds in accordance with reasonable accounting.

Section XVII: When These Regulations Obtain Validity

These Regulations obtain validity when they are published in print.

Section XVIII: These Regulations may be Altered

In accordance with proposals which are approved at a main meeting of the Regional Council, and are subsequently approved by a majority of all eligible voters of the Region at District Meetings, which shall all be held on the same day.

(Approved at a meeting at Sandvik [12], January 11th, 1878)

Nelson Gerrard writes: “New Iceland was never a republic, in the sense of an autonomous state, though this term has been used in some pamphlets and articles, starting in the 1940s. The exact nature of the understanding between the Icelandic settlers (who fully acknowledged their new loyalties and responsibilities) and the Canadian federal government (which was a partner in the venture) is made very clear in speeches made at Gimli in 1877 on the occasion of Lord Dufferin’s visit. The constitution of New Iceland, while a remarkable example of local—even regional—government, is in fact merely a set of by-laws for local government, not unlike those drafted by any organization, but of course relatively comprehensive as the settlement was beyond the boundaries of Manitoba until 1881 when the province was enlarged. Until that time, New Iceland was within Canada’s Northwest Territory, District of Keewatin, and under direct jurisdiction of the Dominion Government. It was never in effect or concept an autonomous state. The use of the word “republic” is entirely inappropriate.” (20 February 2010)

Page revised: 26 April 2014