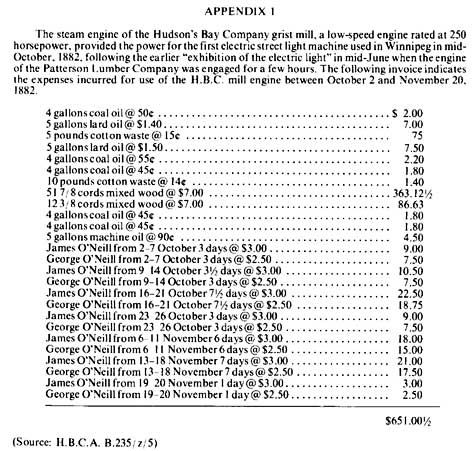

MHS Transactions, Series 3, Number 34, 1977-78 season

|

The riverside community that stretched northward along the west bank of the Red River and westward along the north bank of the Assiniboine River for a lesser distance from their junction, was incorporated as a city in November of 1873. It seems to have skipped that in-between period of being a town, as this term is seldom used in reference to it in old documents and writings. The original survey determined the width of the two main thoroughfares, Main Street and the “portage road” or Portage Avenue as it is now, being set at 132 feet property-line to property-line, with a roadway width of 100 feet. This extreme width seems to have been fortuitously designed with the thought in mind of where to put the snow as it accumulated during a usual or heavier than-normal winter season. The sidewalk width of 16 feet each side, much wider than the usual pedestrian traffic of that time would warrant, thus permitted a temporary storage space for merchandise delivered to the various establishments, and in turn enabled the piling of snow around and about until it was shoveled away or, in many instances here and there, melted of its own accord in the warm days of spring.

The lighting of at least some portion of Main Street must have been the source of many discussions as occasion arose to comment on the Stygian darkness to which Winnipeg was subject during an overcast or moonless night. Side-street development off the two main streets was, at that time, almost negligible. The Point Douglas area, approximately triangular in shape with a base-line along Main Street, bisected to its eastern point by Point Douglas Road (now the main-line tracks of the Canadian Pacific Railway) had an equivalent that ran between Brown’s Creek (between Market and Bannatyne avenues now) along to Water Avenue (then Schultz) and comprising all that area between Main Street and the Red River. These two were the older areas, with more built upon lots of land, although some building had begun a little to the west of Main Street in sporadic attempts to develop that area.

Insofar as it had been accomplished, the lighting was, from all accounts, woefully inadequate. Neither editorial comments on lighting, nor Council discussion of it was effective in producing the desired result. The very width of the two main streets seemed to encourage individuals to deposit rubbish of all description wherever one chose to do so, and there were as well the depressions and holes of uncertain depth that dotted the roadway, many of which retained water from the last heavy rainfall. For variety there were the usual low barricades erected by some zealous individual or contractor to fence off recognizable hazards in the daytime, upon which were hung a lamp or two, lit more in the nature of “dim religious lights” as they were thus referred to, during the dark hours of night.

The first recorded reference to any lamp being used for street lighting, although not officially, was on 6 March 1873. A news item informed that, “Mr. Davis has taken the initiative in street lamps in Winnipeg by placing a very handsome one in front of his hotel. It was got out specially for this objective by Mr. E. L. Bentley (a local tinsmith).” Within a month, “Another magnificent lamp has made its appearance on the street, and this time it is due to Messrs. Cosgrove and Lennon of the Red Saloon, who have ceased to hide their light under a bushel.” Whatever prompted this attempt at street lighting, it can hardly be said that it was either adequate or suitable, the closeness of these two establishments—the Davis House located just north of Portage Avenue and the Red Saloon on the south west corner, and both on the same side of Main Street may have lighted that particular intersection to some extent, but it can hardly be thought that was the motive in their respective minds.

No further reference can be found to individual outdoor lamps that could pass for street lighting duty. Records available do not include much information on these, but here and there are noted items “passed for payment for street lighting” and one of the last was on 14 December 1880, when “E. D. Moore, contractor for lighting the streets be paid the balance owing of $143.45” Whatever the number of lamps in service, the area covered and general overall efficiency, adverse comment was still being directed toward their ability, or the lack of it, to adequately illuminate the streets. For those still inclined to put up a private light, an advertisement of that time read, “The Patent Tubular Street Lamp of which two are on display, one opposite the Post Office, and another opposite the Biggs & Pearson Block on Main Street. The former lamp is priced at $10.00 with a round glass shade; the latter at $12.00 as it is equipped with a square shade.” Both these lamps were described as being “fitted up for the burning of coal oil,” and that they would be kept lit during the winter “where they can be seen by the public and persons wishing to purchase.” This advertisement of February 1880, suggests that oil light was the accepted form at that time.

The Manitoba Electric & Gas Light Company was formed on 14 February 1880, as the successor to the Winnipeg Gas Company of only a few years earlier. Difficulties had beset it almost from its inception, and nothing of its activity is of particular note. No use of gas for street lighting can either be found or inferred, even following a communication to Council from the manager, Sam J. Holley, on 20 June 1880, suggesting that a demonstration lamp be permitted.

Whether the incentive came from some alderman visiting in the east, who had observed the new electric light there, or from some enterprising promoter who, having sensed that at Winnipeg he would possibly find a place to promote his wares, we will likely never know, but on 10 November 1881, the Fire and Water Committee received a communication from Charles T. Yerkes, of Chicago, in which he applied for the privilege of contracting for the supply of electric street lighting in Winnipeg. Well known both as a financier and promoter of various practical schemes, he had, in this instance, deemed it advisable to attend personally along with his communication. Receiving a favorable reception to his proposal, an agreement was drawn, and the matter left to develop as he had intimated. What happened is not known, but on 20 January 1882, the Committee received a letter from his solicitor asking for certain changes in the contract. This was refused, and the Committee replied accordingly, and added “that if the contract was not signed and the necessary work proceeded with at once, the Council would be at liberty to make such other arrangements as they may see fit for lighting the city.”

On 10 March, a similar communication from the solicitor was received and was replied to in no uncertain terms. The reply read, “That Mr. Yerkes having failed to carry out any of the terms of his tender as accepted by the Council, this Committee would recommend that he be informed that this Council do not feel disposed to have any thing more to do with him.” At this meeting another communication was read, this one from a Mr. P. V. Carroll, of New York City, and included with it was a form of contract. Whatever the nature of the contract in general, certain points were left open for final negotiation.

On 14 June, the preparations that had been quietly undertaken a few days earlier were ended, and that evening was a memorable one for Winnipeg. Mr. Carroll had arranged for “an exhibition of the electric light for which he hopes to secure a contract to illuminate the streets of the city,” as it was reported the following day.

Near the Main Street crossing of the C.P.R., the planing mill engine of Patterson & McComb Lumber Company was located. He had arranged for its temporary use to drive the small dynamo that would provide the electricity for his lamps. Four were on hand: one within the mill engine room, one outside on the east, and two on the west side of Main Street, opposite the old passenger station, now in use as a dining hall. For a couple of hours this “exhibition of the electric light” was given, and similarly on the following evening. Reference was made to “the feeble rays of the gasoline lamps in comparison to the brilliance of the electric illumination, that their dimness provoked many a smile.” That summer passed without further reference to the electric lights, other than editorial and news-wire items concerning developments elsewhere, particularly in the incandescent form that Edison was busy perfecting.

16 October was a red letter day for Winnipeg. The following day a front page column of good length was devoted to an article headed LET THERE BE LIGHT in which was set forth “The long-expected electric light made its appearance on Main Street last evening. That it was a success was evident from the start despite a single lamp of the four installed—one at the corner of Broadway; one at the Imperial Bank; one at the City Hall and one at the C.P.R., would not function properly.” In conclusion the article stated,

Our reporter dropped into the lighting factory at the Hudson’s Bay mill near the mouth of the Assiniboine river, and found the establishment in full blast. The Manitoba Electric Light & Power Company, represented by Mr. Carroll, the present manager, had about a dozen lights arranged around one side of the building and which were in the process of adjustment prior to being installed on the street. The system is known as the Weston Patent, and is distinguished from other forms of electric light in that it is pure white. The company manufacturing this equipment is the United States Electric Company of New York, and whose factory is located in New Jersey. Over fifty men are constantly employed assembling these machines. More than 1,800 have already manufactured, the one exhibited here is number 1,191. Compared with other electric lights, it is claimed this one does not in any way change the appearance of objects seen under it. This light is said to be the only white light produced, the Brush light having a blue tint, and the Fuller light a pink tint. Also, it does not heat or vitiate the atmosphere where it is used. Further, the weather has no deleterious effect upon it, the wildest storm doing it no damage. Safety is also claimed for the use of the machinery, there being no danger to life in using it. In every way it gives complete satisfaction.

Alderman Wilson, chairman of the Committee, was present at the demonstration, and he appeared to be well-satisfied and to endorse the expressions of the most enthusiastic of the admirers, and to feel that he and the other members of the Committee had done a good thing for the city in taking steps to secure for the purpose of street illumination the very best light that modern science could produce. The consummation of the scheme now depends on obtaining a Corliss engine, which, however, is not an easy thing, the demand for these being so great.

Within a week, one of the first criticisms of the electric light appeared in the newspapers. It read, “It is a well-known fact that the citizens of Winnipeg are disappointed in the electric light. Do the company producing this light think that an inferior article can be put on the streets and in the business houses and Winnipeggers not discover it? ... Has the light been misrepresented? The general impression is that it has ... Can this light compare with Edison’s, Brush’s, Swan’s incandescent, or the Fuller electric light? ... Let the Council look into this matter before any definite steps are taken. ‘E. B. Tyrell’.” While probably not representative of all those whose opinion differed from the silent majority, there was no doubt some instances of error and even mishap that would cause this infant enterprise—not only for being in Winnipeg but for starting in outdoor operation just as the cold season was advancing to fail. There will be more on this later, but some of the reasons, and the explanations for failure to provide a regular nightly service should, at this time, prove of some interest.

Quotations from the daily press are given in chronological order for this purpose:

Friday, 20 October “One more lamp was placed in position yesterday. As the moon was shining beautifully at the same time, one was reminded that blessings never come singly. The contrast of all this brilliancy with the blackness of last Sunday evening (Oct. 13) was overpowering, but if the electricity and the moon should both go out when the next rainstorm comes, the effect will considerably be the other way.”

Tuesday, 31 October “Alderman Monkman asked how it was the electric lights had disappeared. Aid. Wilson replied, “that a leakage in the steam boiler was the cause.”

Thursday, 2 November “The electric light still continues to be affected by boiler leakage. In disappearing at the first appearance of mud and dark rain clouds, it has only done what other Winnipeg street lamps have done before, but the example is not to be commended.”

Saturday, 4 November “The leaky boiler in the Hudson’s Bay grist mill at the mouth of the Assiniboine River has been undergoing repairs for the past few days, and the work is not likely to occupy more than two or three days longer. One hindrance to the shining of the electric lights will then be removed.”

Tuesday, 7 November “Aid. Wright asked if the lighting of the streets was costing anything at present. Aid. Wilson replied, “that it was costing a small sum.” Aid. Monkman asked if the contracts for lighting with gasoline and electricity were running concurrently. Aid. Wilson replied, “that the City was not under any contract to pay anything for the electric light until the same had been approved by Council.” Aid. Sutherland asked what was the delay with the electric light. Aid. Wilson replied, “that it had been impossible to secure a boilermaker, but one was now engaged, and it was hoped that the boiler would be ready within a few days.”

Thursday, 9 November “THE ELECTRIC LIGHT. THEY ONCE MORE ILLUMINATE THE NIGHT. The electric lights recommenced to shine last evening. Considerable brilliancy was attained at times, but there were some interruptions, as the electricians were simply experimenting for the purpose of adjusting the lamps. They are expected to do more regular service this evening. Messrs. Botsford and Westerfield, the electricians from New York, are working diligently to perfect the arrangements, and it is confidently expected that the lights will henceforward be kept shining every evening. Extreme precautions will be taken to prevent the occurrence of any interruption to the regular service ... As soon as the Electricians have completed the work of adjusting the lamps, and the machinery connected with them, so as to have this portion of the service in working order, they will proceed with the preparation for supplying lights to private individuals in stores and business places, for which many orders have already been received ... It was a cheering spectacle to see the lights once more, even for a few hours, after the many gloomy nights which have been endured, but they were put out all too soon during the evening.”

Saturday, 11 November “THE ELECTRIC LIGHT: THEIR REGULAR SERVICE EXPECTED TO BEGIN EARLY NEXT WEEK: Messers Botsford and Westerfield ... say that everything is now in good order. The frames of the lamps are found to be in such a position, being placed parallel to the length of the street, that they cast a shadow up and down, thereby obscuring to some extent the brilliancy of the effect along Main Street. This will necessitate a change which will occupy two or three days longer ... the effect of which will be to throw the shadows along the various cross streets.”

Wednesday, 20 December “THE ELECTRIC LIGHT: FURTHER CHANGES PREPARATORY TO THE LIGHTING OF THE CITY. Yesterday the thirteen lamps put up for the purpose of illuminating Main Street were taken down from the posts. Scores of people asked what this action meant, and probably not a few went on their way with the impression that all was up with the electric light ... a reporter interrogated Mr. Botsford as to the facts of the case, and ... certain changes had been considered necessary in order to render the lights as effective as possible ... Those who have noticed the arrangement of the lamps have observed that the hood, or green shade placed over each lamp has hitherto been at right angles to the frame. It is proposed to have this changed so as to bring the hood into a line parallel to the frame, and thereby prevent it from coming in contact with the bottom of the latter ... also poles out of perpendicular due to the weight of the wires where they are stretched across the street. The lamps being out of level, the quality of the light was found to be adversely affected thereby, hence a change had to be made, and the blacksmith’s work in altering the frames will probably occupy a few days, and then in a week or so the lamps will be replaced, the wires also being changed in accordance with the telephone company. It is expected that the lights will shine without interruption and with superior splendor when they again make their appearance.”

And to conclude this unhappy condition of affairs, a Report for 1882, covering all of the enterprises to be found within the city, stated:

No city can be said to be fully organized or complete without some effective system of lighting. Private enterprise during the past year had endeavored to supply this want, and the struggle between gas and electricity has been a keen one. The city has, however, suffered from too much experimenting on the part of the authorities, and it is just a question if the city could be more satisfactorily lighted by keeping the control in the hands of the Council. The electric light, upon whose success the Fire, Water and Light Committee placed so much confidence during the year, had not been attended with the anticipated results. The trials made were for a few nights fairly successful, but were of such a spasmodic nature as to be the next thing to useless for the practical lighting of the city. The authorities can not be congratulated on the efforts put forth to light the city during the past year and a good field of operation is left open in this direction for the new Council.

All of which brings the story to the end of the year 1882. Earlier it was mentioned that Mr. Carroll was the manager of the Manitoba Electric Light & Power Company. The first notice published in the Manitoba Gazette for the incorporation of the company is dated 30 June 1882, which would indicate an assurance on his part that all would be in legal order for his anticipated dealings with the Council. In part it read

for the purpose of providing the necessary machinery and power to produce electric light and for producing such light and lighting therewith cities and towns and public and private buildings and for producing power for the working of machinery for other purposes. The company intends to carry on in all the cities, towns and villages in the Province of Manitoba, having its chief place of business in the City of Winnipeg.

The names of the applicants were: Peter V. Carroll, of Winnipeg, Gentleman; Charles F. Boughton, of Winnipeg, Lieutenant-Colonel; James Austin, of Winnipeg, Gentleman; E. F. Radiger, of Winnipeg; C. F. Strohm, of New York City, and other persons who may become shareholders in the company. It cannot be confirmed whether Peter Carroll was acting for the United States Electric Company of New York, or only on his own as an entrepreneur.

The year 1883 started off rather auspiciously. The first regular meeting of the Council occurred on 1 January (New Year’s Day was not a recognized holiday then), and among the business transacted was, “On recommendation of the Committee to Council, a contract will be entered into with Peter V. Carroll for the lighting of Main Street by the electric light ... within a few days.”

These news items also appeared “The lighting of the electric lamps was resumed on Saturday night (30 December), but the weather was seemingly too severe, judging from the flickering character of the light,” and “The electric lights began the New Year somewhat promisingly. The illumination of last evening was superior to most of the attempts previously made, leading to the hope that a satisfactory working order may yet be attained.” Throughout January, the following information came to light

4 January. The electric light did good service last evening ...

5 January. The electric light did not show up to advantage last night ...

6 January. The electric lights on Main Street were shining brilliantly again ...

Investigation of this absence disclosed that “the breaking of the valve of the steam pump used to pump water into the boiler of the engine caused the shutdown. Lest it be thought that the electrical apparatus was at fault, the manager has deemed it advisable to make the foregoing explanation. The accident is supposed to be the result of the present severe frost. The machine shops will be visited today with a view to immediate repairs. Had the accident occurred either in Chicago or New York, there would have been little or no interruption to the light, as a new pump would have been on hand in very short order.” And in a lighter vein, on January 8, this was given, “The light opposite the Post Office continues to manifest a variety of eccentricities. It might be interesting to enquire whether this is in any way due to the magnetic influence of the accumulation of epistolary effusions, as the lights elsewhere on Main Street were shining magnificently last night.” Throughout the month service was still sporadic, no doubt due to the weather as much as anything else.

On 23 January, the City Engineer, H. N. Ruttan, tendered a report to Council, in which he summarised his investigation of the whole matter of the electric light service: “I am fully convinced that the light is satisfactory so long as it is in operation, but there are frequent stoppings that have to be obviated. I am informed by Mr. Carroll that he has a great number of difficulties to contend with, those mainly responsible for, and still capable of correction, are:

- The temporary engine which he has engaged to produce the power cannot perform the requisite number of revolutions per minute to give the maximum intensity of light.

- The carbons that he presently uses are not so good as they should be, but more perfect ones have arrived today.

- From the intensity of the cold of the past fortnight the glycerine employed to actuate the carbons has frequently congealed and put out the light, although it is mixed with five times its bulk of alcohol. He hopes, ere long, to procure a fluid which will not be affected by the cold. At present a man is constantly employed on the street to rectify these mishaps within a few minutes.

- Mr. Carroll informs me that it is his intention ... to procure proper engines to give the maximum revolutions required.

- The circular shadow, or ring, noticed on fresh-fallen snow more than on other occasions cannot be explained. No man has the answer to this. Contrasting the electric light with the other illuminating powers in the city, the former has much to recommend it, and in point of utility, even taking into account the occasional stoppages, it far exceeds the gas. At the present time we have been without the last mentioned illuminating power, and cannot ascertain when it will again be in operation.

At the meeting of Council on 30 January, the following action was taken, “That the City Engineer having reported favorably on the electric light, your Committee would recommend that the lights be accepted,” and by this recommendation had signified their approval, and the Mayor was instructed to sign the contract. When it came time to deal with Reports, Ald. Burridge read a letter he had in hand from a Mr. Munsie, in which he offered to introduce the Brush electric light. Thus the month of January passed, and all seemed to have settled down so far as could be observed.

On 2 February, when the Council again met, a communication was received from the Manitoba Electric Light & Power Company, along with a Bill of Account for $594.00. The letter explained that the Company had supplied electric lighting for the City as best it was able for the past four months, and had not rendered a bill. They were still experimenting with various solutions to correct the irregularities that were evident, and since 1 January the terms of the contract had been met. The charge now being made was for twelve lights for thirty-one nights, and for one light for twenty-four nights, which at $1.50 per light per night (p.l.p.n.) amounted in all to $594.00. A lengthy discussion ensued, involving the quality of the light in comparison with some other cities of aldermanic knowledge, or at least comparable to that exhibited last June at the Main Street crossing of the C.P.R. when the engine of the Patterson planing mill was used.

Present at this meeting was James Munsie. From all accounts, he had been in Winnipeg since November, because on 10 November it had been announced that “The Brush Electric Light Company proposes to form an organization in this city, for the purpose of introducing their system of electric lighting in Manitoba.” Nothing of his activities since that time was noted, possibly due to the confining winter season. Although he represented the Brush Electric Light Company, he was only in attendance as an interested spectator. Later, when he was asked by a reporter if he cared to express an opinion on the electric light, he said the contract term of six years was too long, in view of the rapid development in the electric lighting art. If a shorter term was given, he would then submit an offer to the council. When questioned further regarding the difficulties being experienced by the present supplier, he replied that his system would use the Swan incandescent light which, by its very nature, would shine with the utmost steadiness. (Note—Here, if it could be proved that he was then doing so, would be the use for the first time locally of the incandescent light.)

A word or two of explanation regarding the Brush Company may be in order here. Charles F. Brush had improved upon the early arc light mechanism sufficiently that by 1879 he was offering both the Brush arc light, and the Swan incandescent light, simultaneously. It must have been in rather a tongue-in-cheek manner that the offer to light the street with incandescent lights was given, as those lights could never approach the brilliancy of the arc lights, rated at around 2,000 candlepower.

On 6 February, the Council had to consider a report from the Fire, Water and Light committee that requested “the Company agree to have struck out the word ‘either’ before ‘by electricity,’ and ‘or otherwise’ after ‘electricity,’ following which your committee would recommend that the contract be confirmed by the Council.” And on a finer point, it was suggested that as the thirteen lights had not all been in service for the entire term now up for consideration for payment, the agreement with the Company be modified covering those parts for: reduction in the price per light per night; length of contract; and more specifically, the exclusive right to light the streets of the city by electricity. At some time during the proceedings the Council was informed that hereafter they would not be dealing with Peter Carroll, as manager of the Manitoba Electric Light and Power Company, but with James Austin, the secretary of the company (as a company, they had no legal right to exist, the Letters Patent for incorporation had not been granted).

A little delaying tactic had also occurred: when the bill for $594.00 was presented to the City Engineer, one Thomas Parr, for his approving signature, he protested that he had not received any official intimation of there being any electric lights in use in the city. He also had not been furnished with a copy of the contract covering the use of such, if there were any. When he suggested the Deputy City Clerk should be asked to lay the account before the Fire, Water and Light Committee which was acted upon, the City Clerk, Mr. Brown, said that would be of no use as nothing could be done until the account had been certified by the City Engineer, Mr. Parr, (at that time the City had five or six men who were designated “City Engineer,” and acted upon assignment rather than any specific duties).

On 7 February it was reported that “The electric lights went out last night. As some of the Aldermen had threatened to freeze them out (by refusing to raise the number of lights above thirteen which the company said was required if they were to be able to meet their ordinary expense) it would almost seem as if the freezing process had begun. The lights have already stood a temperature of 46 below zero without being frozen out; hence it would be interesting to know exactly what greater degree of cold the hearts of the Aldermen can bring to bear on them in case of emergency.”

In order to hasten matters, at the meeting of Council on 13 February, the Fire, Water and Light Committee recommended “the Electric Light Company be requested to agree to the alteration in the wording of the contract, as Mr. Austin the secretary of the company and as the assignee, has already agreed to the erasure ... and that the following proposition be made to the Electric Light Company: that the number of electric lights be increased to thirty and the City to pay for all over thirteen at $1.00 p.l.p.n. up to forty.” Apparently these terms were not agreeable to the Company and no reply was received regarding further service. A small item in City Notes disclosed that “There was no electric light last evening, the manager having decided to close down until a satisfactory settlement of all matters in dispute with the Corporation can be effected.” When Aid. Nixon asked if the Committee were aware there were no electric lights in the City tonight, and that there had been none one night last week, and what was it proposed to do about it, Aid. Sutherland replied, “He had been aware beforehand, that such would be the case,” to which Aid. Montgomery added, “A little trouble had arisen.”

The original bill for $594.00 which had been presented to Council on February 6 did not receive approval until 7 September, when, amongst others outstanding, all were cleared off. An item in City Notes is interesting: “Mr. E. M. Wood, City Solicitor, has garnisheed the 500 and odd dollars due by the City to the Electric Light Company. Messers Wood and Radiger—the latter being one of the shareholders of the company, are said to have endorsed a note for $1,000.00 for Mr. Austin and which fell due last Saturday, and for which they had to provide themselves as Mr. Austin was away in the east. Hence the garnishee.”

On 20 February, the Committee recommended to Council that “Inasmuch as the Electric Light Company have failed in the performance of their contract with the City by not lighting the city for over a week, that the said contract be annulled and cancelled so far as the Corporation is concerned,” which, when brought up again in Consideration of Reports, was more meticulously worded as, “That whereas a contract was entered into with the City Council bearing the date 22 June 1882, by Peter V. Carroll of the City of New York, and that by the terms of the said contract he had agreed to furnish the city with thirteen electric lights, and which he had agreed to keep properly burning, and whereas the said contract, if it has been broken, by him or the Electric Light Company to whom he sold the contract, in that he or the Company has not kept the city lighted successfully, this Council therefore declares the contract, if broken, to be annulled.” All this drew a scathing editorial urging the Council to give some consideration to the position of the Company, and its attempt to operate as best it could under such a contract. It urged the Council not, at this time, to decide upon the worthiness, or otherwise, of the contract, but to pay the bill. At this time the entire contract was published, and doubtless many persons were now seeing it in full for the first time.

A little nudge was given toward getting some action into the stalemate when, at the next meeting of the Committee on 27 February, among the communications was a Writ of Summons for $1,000.00 debt and $40.00 costs owing the Manitoba Electric Light and Power Company. There also was one from Frank Robinson, offering to resume the lighting of Main Street with gasoline (oil) lamps on the same terms as before. A disturbing note entered at this time relative to these so-called gasoline lamps: an item in City Notes read “There has been reported of late a number of explosions through the city apparently due to the inferior quality of the oil brought into the city recently. A number of lamps had exploded in the C.P.R. waiting room, and two if not three of the recent fires had been due to the same cause. It was given that it might be well for the Collector of Inland Revenue to take cognizance of this, and see that the evil, if it does exist, is remedied, as the complaint is not confined to any limited number of persons or localities, but is general over the city.”

Now, figuratively speaking, the fat was in the fire. Nothing was being done by either party. The sentiment expressed earlier by one alderman when this Council, faced with having to re-negotiate contracts and terms to which the former Council had committed the City was still in order: the matter of the gravel pit, the bridges, and now the electric light contract with a fixed charge and a six year term, was just too much. Ald. McVicar reaffirmed the remark of Ald. Nixon, when he suggested that the Council of 1882, who had been responsible for such things ought to be drowned. One way that would bring the Company around would be to insist that they continue supplying electricity for thirteen lamps, and if this could only be done by incurring an increasing loss, they would soon acquiesce.

At the meeting of Council on 5 March, they were informed of another Writ of Summons, this asking for $100,000. damages and costs. But also, on a more cheerful note, there was a tender submitted by Mr. Munsie on behalf of the Northwest Electric Light & Power Company, for supplying not less than fifty electric lights at $1.00 per light per night. And to lend emphasis to any further progressive action a newspaper article remarked on the situation, titled OUR STREET DARKNESS—THE WINNIPEG STREET LIGHTS LIKE THE WILL O’WISP; THE MORE YOU CHASE THEM THE MORE THEY ARE NOT THERE and with remarks given at some length to the situation. It also implied the city must rely for a little longer on the moon and stars, hotel lamps and shop windows, for its street lighting.

On 28 March the Council made an offer to offset one from the Company which now proposed that, for the amount of $50,000. they would transfer their whole plant to the City, or failing that they would, if satisfactory arrangements were made, have the lights again shining in two or three days. Council proposed “that if this offer is accepted it cancels all former contracts, if such exist, with the City, and it is not binding on the City to light more than twenty lamps per month, if they think it to be wise.” On 2 April a meeting of Council directed that the Company be given one week from that date to answer the proposition. No answer was received, and at a meeting on 13 April, Council considered the acceptance of the tender from the Northwest Electric Light & Power Company, but only for thirty lights at $1.00 p.l.p.n., not as Mr. Munsie had proposed that it be for fifty and for only three years. The new proposal by Council stated “that Main Street from the Assiniboine river to Point Douglas Avenue be satisfactorily lighted within three weeks from the signing of the contract.” It was accepted, completed and signed on 17 April, and drew favourable comment from all sources.

Those who were petitioning for this new company were John Charles Bridges, Esquire; Horace McDougall, Electrician; Frank Graham Walsh, Hon. Corydon P. Brown, Gentleman; and James Ferguson Munsie, Contractor; all of Winnipeg, and the intent of the company seeking a charter was “the purpose of lighting by electricity and supplying with electric power, cities and towns in the Province of Manitoba, and supplying the citizens thereof with electric light and power.”

On 1 May, it was reported that “The new electric light company have succeeded in making arrangements with the old company for the purchase of all their plant, etc. and took possession of it yesterday. The work of lighting the city will be pushed on with vigor, and Main Street will be again lighted within the time specified in the contract.” That which was actually taken over could only have been the arc lights—the thirteen which were out on the street, and possibly a few extra in stock, one dynamo—at least, if not another as a spare machine; a circuit control panel of appropriate design; and a quantity of insulated service wire, some already strung along the street on insulators, and no doubt some in coiled or reeled stock. No valuation for this is given, so it is a matter of speculation regarding what amount of cash actually changed hands.

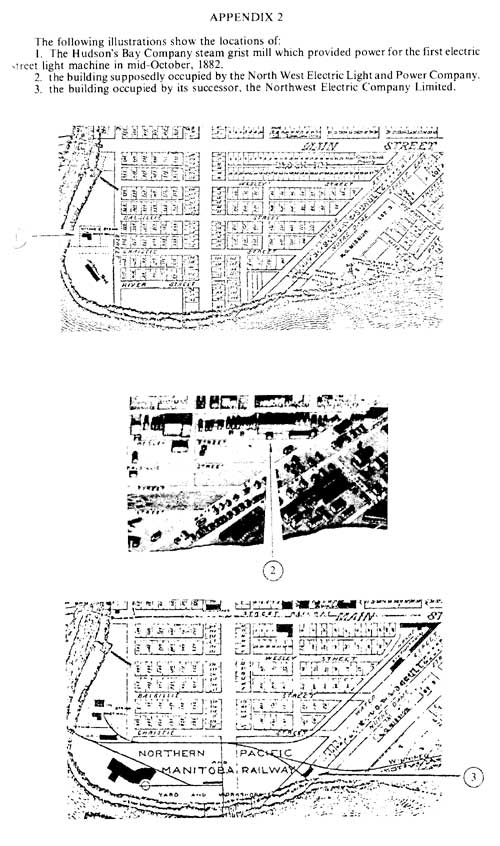

On 23 June, a report in more detail was given. In full, it read “For the first time the power of the Northwest Electric Light and Power Company was used last night in lighting the street(s). There was a marked improvement in the light. The nominal power of the engine is 30 H P., and has capacity in building room and shafting for forty lights. They have now dynamos to give twenty five lights, and the secretary has been instructed to order at once a 30-light dynamo, to be used exclusively to supply the lights required by the city Council for street lighting. The company are now arranging for the purchase of a 75 HP. engine, which will be placed in a station at once to supply the power necessary for private lights. They are having, besides the city contract, a large number of orders for lights for public buildings, such as churches, hotels, factories, etc.” From this, we know that the company was established sufficiently to carry on their business but from where? Accepting the report at face value, the engine on order for the private lighting business of the company “will be placed in a station at once,” and this, along with where the other engine that would be supplying the power for lighting the street lamps was located, poses the question, where was the business address of the company located? For this information, the city Directory is the only source available today, and it was given as “Electric Light Station Wesley Street near Water” for six consecutive years.

Although the deadline of three weeks from the time of the signing of the contract on 17 April had been exceeded by a period of almost seven weeks unless power was being obtained otherwise, but more likely due to being in mid-summer when daylight was at its longest, it had not been considered a drastic omission. And the arc light was the only electric light form to be used in Winnipeg for lighting the streets for many years to come. The story from this point is only concerned with the changes that occurred within the next few ears regarding tender submissions, and to whom the contracts were awarded. James Stuart entered the Winnipeg scene in 1882. Arriving from Toronto where he had been with the Consumers Gas Company, he was given the task of setting up the plant of the Manitoba Electric & Gas Light Company, successor to the Winnipeg Gas Company. Successfully accomplishing this, he remained with the company as superintendent. While no reference can be found to any development of the electrical side of their business, in 1886 he is found to be also superintendent of the Northwest Electric Light & Power Company.

Having gained the contract for the street lighting for a period of three years from April 1883, and the number of lights being increased from the original thirteen as the need arose, the Northwest Company no doubt were also looking for private lighting as a means of increasing their revenue. What provision it was making for this service is now unknown, as private lights indoors would require service an hour or two before street lighting during the dark afternoons of those months of the year having fewer daylight hours.

James Munsie was associated with the Brush Electric Light Company in Winnipeg, probably as an agent for their products, which included both the Brush arc light, and the Swan incandescent light. As such he was able to provide a service that Carroll could not, as his line was strictly the arc light provided by the United States Electric Company. It has to be assumed, therefore, that some cooperation between these two men existed for promoting their respective products, for Munsie did not have access to a source of electric power. No advertisement has been noted for the incandescent light at that time, the first mention of private lighting occurring on 18 May 1883, as “the Opera House has developed into a great success ... the lights within the building are remarkably good. There are only some half-dozen as yet, but these are superior to any that have yet been seen in the city.” These were arc lights, and the electricity for them was supplied from the nearby biscuit factory of Mr. Chambers, (the Princess Opera House stood on the corner of Princess and Ross Avenue; the factory stood and still does, on Ross Avenue just across the lane from Princess Street.) An additional light was installed on the corner outside the Grand Union Hotel just across the street, and others were to be added in the vicinity as soon as practicable. All this is mentioned only to show that some private lights were being serviced, but not from street lighting circuits. No doubt many of the merchants were anxious to try out the new lighting, and the high ceilings of the newer stores provided the necessary clearance for the suspended arc lamp structures. Some were installed within the front doorway space where, as was usually the case, side windows flanked it, and the brilliant light would provide some illumination for them also (most stores on Main Street were only 25 to 40 feet in width; a few others were 50 feet). Gas lighting made inroads as the mains extended throughout the city. As the piping was usually run in the open across the ceiling in the older buildings, so also was the wiring for the electric lighting, so little choice was available for this convenience, and the slight disfigurement of the otherwise clear ceiling would have to be regarded as a concession to progress.

During 1884 and 1885 there is no mention of further private lighting service, only an increase in the number of street lights as authorized by Council. On 30 April 1886 the contract for street lighting was up for renewal, and tenders were sought. The Northwest Company were successful in obtaining this contract but through F. B. Wilcox, who now had succeeded James Munsie. But something was afoot that has not come out into the open: James Stuart is noted for now being the superintendent of not only the Manitoba Electric & Gas Light Company but also for the Northwest Electric Light & Power Company. Within a year or two, the street lighting section of the Northwest Company was removed from the Wesley Street plant to the Gladstone Street plant of the Manitoba Company. The implication is that the private lighting would be carried on from the more central point, and the street lighting, less centralized, from the parent plant. Was this an intentional splitting of the electrical business? From all accounts, no other electrical service was being promoted from the Gladstone Street plant of the Manitoba Electric & Gas Light Company despite their somewhat grandiose name.

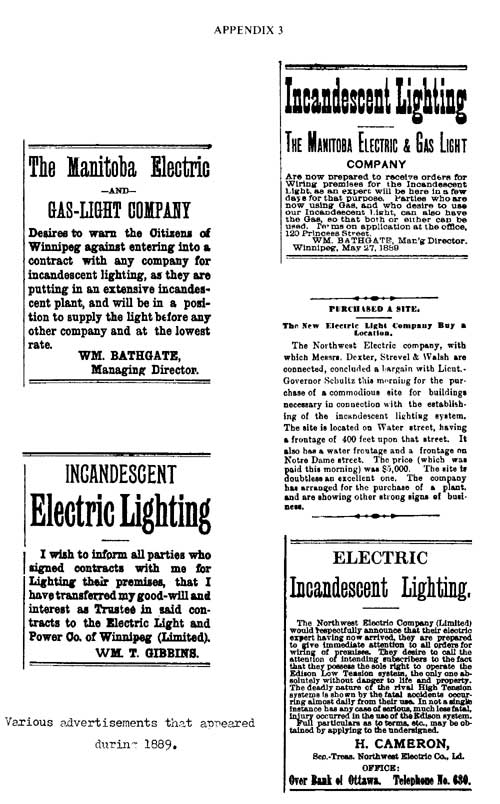

Not until the summer of 1889 is any inkling found of private electrical lighting from the Manitoba Company. At that time an advertisement was placed, stating “Citizens are warned against entering into a contract with any company for incandescent lighting other than with the Manitoba Company as we are expecting an expert to arrive shortly to discuss the matter with prospective customers.” And alongside it soon appeared one that read “I wish to inform all parties who signed contracts with me for lighting their premises that I have transferred my good-will ... to the Electric Light and Power Company of Winnipeg (Limited). ‘Wm. T. Gibbons’” and who he was or they were remains a mystery up to this day. The company is briefly referred to in a Privy Council hearing in London in 1912 in connection with a suit between the Winnipeg Electric Street Railway Company and the City of Winnipeg, wherein is mentioned “the Electric Light and Power Company of Winnipeg, of which nothing more is noted.”

On 27 May 1889, the following advertisement appeared, “The Manitoba Electric Company are now prepared to receive orders for wiring premises for the Incandescent Light as the expert has arrived” and other advices from time to time concerning the arrival of material for the plant necessary to provide the incandescent light service within a few weeks time. This then, at least identifies the time of incandescent light service from the Manitoba Company, but what of the service being provided earlier by the Northwest Company? No records exist for that now, but surely James Munsie—or his successor—would have been involved in this form of lighting since early 1883 or even a little later. No record for erecting poles or stringing wire nor any list of customers served remains today. But when in 1888 the word was out that the Northern Pacific & Manitoba Railway Company were planning to build along Water Avenue from the river bank right up to Main Street, where they were proposing to erect suitable buildings for terminal offices and a station, and hopefully a magnificent hotel on the corner, all this necessitated some expropriation and changes to the property immediately adjacent, which would involve the northern end of Wesley Street. The site of the Northwest Company plant would be required, and it is only from old maps that this location and building, can be determined. Faced with a removal, and for other reasons of corporate identity, a new company was formed, this time as the North-West Electric Company Limited. They were able to locate on land at the foot of Water Avenue on the north side and on September 6, 1889, is noted, “Mr. Stuckey, a wiring expert from the Edison Company in Minneapolis, has arrived in Winnipeg to string the wires for the new Northwest Electric Light Company ... the engine house and work shops, at the foot of Water Street, are nearing completion.” Subsequent to this, however, in Communications to Council for 17 September 1889, is given “H. Cameron, secretary of the Northwest Electric Company, asking permission to erect an engine and hollers,” for which permission was then given but to be erected to the satisfaction of the City Engineer.

The applicants for the incorporation of the company were George Strevel, contractor; Jefferson Davis, electrician; Henry J. Dexter, solicitor; Frank G. Walsh, gentleman; and James N. Johnston, accountant, and the intent of the company was “to acquire, build, construct, erect, operate and maintain electric lighting system or systems, electric street railways, electric motors or other electric power in the Province of Manitoba.” The directory of 1890 lists the North West Electric Company at 55 Water Avenue, with its physical plant valuation as: building, $14,600.; machines, $22,040.; electrical apparatus, $18,190; and Edison company royalties, $16,000. The last item definitely indicates a commitment to the Edison system of distribution and also possibly that some of the electrical machines, still covered by patents, would be in use.

While all this activity was going on downtown, what of a similar nature was being performed by the Manitoba Company? Wire stringing was in progress, and that is almost another story. Poles and their use were the sole property of their respective owners. The telephone company, the telegraph company, and now these two electric light companies, one of which already had the street lighting contract and for which poles had been erected separately where necessary: all joined in protest against more poles being placed on the city streets. And to make matters worse, both the telephone and telegraph companies used bare wire for the outdoor circuits, and now the North West Electric Company was using bare wire also, as their Edison low-voltage System justified this use. The Manitoba Electric Company used the Westinghouse high-voltage system for alternating current for which insulated wire for at least part of the system was mandatory. Provisional permits were being given by the Council, despite heavy opposition from both the separate companies and the public. Matters were finally solved by an amicable agreement for the time being, and the work proceeded. One aspect of the situation came to light when this little gem was discovered. William Bathgate, manager of the Company, was asked, “whether there was safety in having wires on the poles carrying around 1,000 volts for his customers circuits.” He replied “this was only for use on the poles, as for each customer there was installed a converter (transformer now) to tap off only around fifty volts for actual use by the customer.” This is interesting as it sets the voltage for the incandescent lights at that value, which the rival North West Company, committed to the Edison system, also was using.

Whose premises their first contract was for, and when it was first energized, has not been discovered, possibly because they were carrying on with those of the earlier company and additional contracts as they were acquired. On 6 September 1889, it was noted that “the Manitoba Electric & Gas Light Company’s incandescent system was turned on for the first time in Seed’s fruit store by a wire attached to the regular city service.” Seed’s store was located near the corner of Portage and Main Street. And on 14 September the following item appeared, and as one being typical of that time is given here in full—“The North West Electric Company has issued a neat six-page pamphlet containing useful information on electric incandescent light. It sets out the nature of this light and its relative merits compared with gas and coal oil for interior illumination. It deals with the effect of incandescent light on the eyesight, its effect on the health, and takes up the question of safety of this light over all others. The pamphlet closed off with, “Hermetically sealed in its crystal chamber, protecting from fear of fire and explosion, a fragment of carbon glitters and glows, rising to the light of a taper, brightens and broadens, and finally illuminates with the effulgence of day.” But for all this, no record has, to date, been found for the turning on of the first service from the new plant on Water Avenue.

In connection with this preliminary activity now taking place by both companies, a word or two on what this new convenience would cost the customer may be of interest. In the order of that company which seems to have supplied this private service first, through their inherited contracts which were at first only for arc lighting, the new form of incandescent light was now to be a reality for indoor illumination. The quotations now given are from actual reports for that service at that time. Both companies supplied the lamps required, for which a charge of $2.00 was made, the lamp to be the property of the customer. Whether these were interchangeable between company use is not known: The Manitoba Electric were promoting the Westinghouse alternating current system and were using the Sawyer-Man lamp which was made to fit the Thompson-Houston socket. No doubt the North West Company, committed to the Edison system, was using the Edison lamp which was the only one with a screw-type base, all others being the bayonet or pintype. Whether this persisted until 1889 is unknown, as the merger of the Thompson-Houston, Edison Electric Light, and the General Machine Company was about to occur around 1891, and possibly some arrangements were being worked out prior to this date. But it is known that the voltage for these lamps was 50 volts, according to both Wm. Bathgate referring to it, and the North West Company stating that their low-voltage system involved absolutely no danger with its use.

As to the rate being charged for the electric service, the North West Company stated: “As regards prices, Mr. Cameron says that they guarantee a first class light ... If the public do not receive this they are not charged at all. The cost of the lamps is $2.00 each, and become the property of the customer. Light is furnished at 0.9t per hour net, the same figures exactly as in St. Paul and Minneapolis.” Limited service was provided which was ambiguously given as “The current may be turned on at any time between the hours of 4:00 p.m. and daybreak in morning,” a condition which left much to be desired.

The Manitoba Company were more specific, stating: “The lamps supplied are nominally 16 candle-power, for which the charge for use is 1.0¢ per hour less 10% (for prompt payment?). When the lamps are put all through a house, the charge is 54¢ a light per month, or 1¢ an hour, and less 15% if a meter is used. Stores may be on one of a dozen different ways by which the tariff may be regulated, but usually it is on the basis of 1¢ per hour.”

A little calculation provides the following information: a 16 cp. lamp of 55 watts power consumption per hour would use, on a three hours use per evening, 55 x 3 = 165 w-h. The charge being 0.9¢ per hour, this rate for 1,000 hours use, or 1 kilowatt-hour would be 1000/165 x 2.7 = 16.36¢, for an average thirty-day month would be 165 x 30 x 16.36 = 81¢ for a single light, or lamp. While the rate of 16.36¢ per kW-h is not high for that time, it was for severely restricted service. Not until 1900 was 24-hour service provided.

And now, in conclusion, it may be in order to give the following information as to the fate of this new North West Company which was already in the books after only a three year start from 1890 and as its predecessor Northwest Company was in the three years from its start in 1883 until 1886 when James Stuart of the Manitoba Electric Light & Power Company also was superintendent of the Northwest Electric Light & Power Company. As noted on 9 November 1893, “Manager Campbell of the Winnipeg Electric Street Railway Company states that the present small number of cars being operated was due to changes that are being made in the power house, where a new engine is being put in to run the electric light plant and thus set the other engines free for the railway work entirely. The cars thus laid off are being overhauled for the winter season ...” And, as a sequel to this, the following remarks are found in a report of 1898 to the manager for the Annual Report to the Directors, that “The work of converting those services acquired from the Manitoba Electric & Gas Light, and those of the North West Electric Company in the area bounded by Graham and Assiniboine Avenues and Main and Vaughan Streets has been almost completed. This includes 28 arc lights in six rinks within this area, and 40 incandescent light services. We have run out of wire to continue this work for this year, and regarding some of the services, a few of those of the North West Company are having to be charged on a flat rate basis as they were covered with chemical-type meters which we do not use. A supply of meters, as well as wire will be required for the forthcoming year.”

The end of the North West Electric Company had already been planned for in 1895, and now in 1898 it was a fact: their books were closed off in June 1900, apparently having at the end outlasted the Manitoba Electric & Gas Light Company electric service by two years. The accounts for all electric service, both for the street railway and the commercial which at that time included the street lighting, were withdrawn from the books of that company at the end of 1898. Now all electric service other than that in a few industrial businesses would be provided by the Winnipeg Electric Street Railway Company from their Assiniboine Avenue steam plant. In 1900 the city, having undertaken to build a new waterworks plant to assure the citizens of a supply of pure water from wells rather than from the Assiniboine River as formerly, had decided to more economically operate this plant by giving it some night work to perform when the power need for water pumping was at its lowest; the street lighting was now to be incorporated into their operations. At long last the suggestion that had been made in the Report for 1882 became a reality; the city could be more satisfactorily lighted by keeping the control in the hands of the Council.

From the story of the introduction of the first electric light into Winnipeg, we know that both the arc and the incandescent were on hand in the latter months of 1882, and it must only have been the vicissitude of those early arc lights, coupled with the lack of proper power plant, that prevented both the arc and the incandescent light from being in use at almost the same time. From the above, it would appear that a period of six years separated them from 1883 to 1889—which now seems almost unbelievable. It is therefore to be hoped that this attempt to assemble the bare facts of the advent of electrical illumination in Winnipeg, somewhat sketchy as it is for those portions that now have to be regarded as missing links in the chain of consecutive events, impossible to verify even from hearsay recollection, may, for a moment or two at least, cause some retrospection into the life and time of an earlier age in the history of Winnipeg.

Much of the information given in this paper was culled from the columns of the following Winnipeg newspapers: Manitoba Free Press, Free Press Evening Bulletin, the Sun (in three daily editions), and the Times. In addition, the author would like to thank the staffs of the Provincial Archives of Manitoba and the Winnipeg Centennial Library for their kind assistance. And finally it must be mentioned that the paper could not have been written without the assistance provided by the City Clerk, who allowed the author to peruse old Minutes of Committee and of Council in order to substantiate that which otherwise appeared in print.

Various advertisements that appeared during 1889.

Page revised: 5 October 2012