by W. Friesen

MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1962-1963 Season

|

In 1875, J. C. Hamilton, a visitor to Manitoba from Ontario, heard frequent mention of the newly-arrived Mennonites. On his way down the Red River to Winnipeg by Red River steamer, he saw several groups of them. On his way back by stage coach as far as St. Paul, he made the personal acquaintance of two of them.

In the following year, he published an account of his visit in a book entitled The Prairie Province. The main purpose of this book was to describe the resources of Manitoba and to report the progress of settlement in various parts of the province. However, it also contained interesting references to various people whom he met during the course of the journey.

He was apparently impressed by the large number of Mennonites that were coming to settle in Manitoba, for he mentions them at some length in several places in his book. The more important of his references to the Mennonites are given in the quotations that follow. They indicate the impression the Mennonites made on the author and should serve also to give some idea of the reaction of the local inhabitants to the arrival of these strangers from a distant land.

"The broad faces and stout forms of Mennonites, dressed in brown homespun - men, women, and children, here greet us in numbers ... The purser informed us that several parties of them passed in by boats this season. They have generally large families-children of every age up to puberty. One man had his second wife and twenty-three children.

"The Rat River settlers broke about three thousand acres of land, and sowed the same last spring, but suffered greatly from the grasshoppers. The thirty families that settled at Scratching River had good crops. The Pembina Reserve has only recently been made and has upon it about three hundred families."

In his description of the return journey, Hamilton makes reference to a number of passengers on the stage coach in addition to the two Mennonites already mentioned. Among them were an American business man, a Canadian senator, an ex-ferryman, and a young man whom he describes as "the smart boy from Ontario".

"We are now joined in company by __, and two Mennonite gentlemen, intelligent, plainly dressed, having broadcloth overcoats lined with dressed sheepskin, the wooly side next to the person. They were on a business trip to St. Paul, but would soon return.

"Our two companions passed the time in chat, or with their pipes and a religious book which one of them had. We asked how they liked Manitoba. 'O', said they together, brightening up, 'A guttes-land, schones-land'. 'A guttesland' you say and I believe you old Mennons', said the ex-ferryman, rousing himself, 'and you broad brims have the best of it; you get a free passage from Quebec, and then squat close to the river, with one hundred and sixty acres, a free gift to each of you, and the railroad soon to pass your doors. Then you have no fighting, no lawyer's bills, and I guess but little doctor's stuff to swallow or pay for, you'll soon make this a land of Goshen.' 'How's that about fighting and doctors?' put in the smart boy, while the two Mennonites looked on half understanding and much amused. 'Why these old sober-sides are a sort of Dutch Quakers', replied the ferryman, 'but I would not advise you to tackle any of their boys without taking their measure well. If they don't strike from the shoulder they may squeeze like the bears of Russia, from which they came, being invited to leave because they won't go soldiering for the Czar. I'm told they settle their disputes by friendly arbitration, hate the smell of gunpowder and as to physic the very women are stronger than our average American men. When I was coming down the Old International, one of the fraus borrowed a mattress, disappeared down the hatchway about noon but was up again before sunset with a little Mennon in her arms, whose first squall was heard about the Pembina. Ask purser Smith and he'll tell you all about it.'

"The smart boy ... broke out with a rattling ditty as follows:

The Mennon Bold

A beautiful home has the Mennon bold

His harvest he reaps and he sells it for gold;

From lawyers' bills and from doctors' pills

He is free as the wind of the western hills.

The prairie land is a beautiful land

The chosen home of the Mennon Band.He never would fight for Gortchekoff,

And the word of the Czar was "drill or be off!"

O'er Gitchie Gumu, then away came he

With his frau and his kind, to the land of the free.

The prairie land is a beautiful land

The chosen home of the Mennon Band.The Metis may laugh by the River Rat,

At his sheepskin coat and his broad-rimmed hat,

But he drives his steer and he drinks his beer;

And a happy home is the home he has here.

The prairie land is a beautiful land

The chosen home of the Mennon Band."

Hamilton's light-hearted but sympathetic and fair-minded references to the Mennonites, and the comments and views expressed by his fellow travellers probably reflect fairly well how the man on the street felt about the Mennonites and the limited extent to which he had learned to know them.

Who were the Mennonites? In the following pages I shall deal briefly with this question before proceeding to my topic proper. Then after telling the story of the origin and growth of Steinbach, I shall spend some time in discussing a topic that has always been important to the Mennonites, the education of their children. For the source of much of the material on Steinbach I am indebted mainly to three local historians of the Steinbach area, Mr. G. G. Kornelsen, deceased, Mr. K. J. B. Reimer, and particularly Mr. John C. Reimer.

Who are the Mennonites? How and where did they originate? Most of the Mennonites who live in Manitoba today are descended from Frisian farmers and Flemish artisans who formed Anabaptist groups in the early years of the Reformation, beginning about 1530. As time went on they were joined by Anabaptist refugees from various parts of Germany and a few from Switzerland. The Anabaptists were Protestant sects who felt that the reforms of Luther and Zwingli did not go far enough. They believed in complete separation of Church and State, abstention from taking of the oath, and non-resistance. They would not accept the infant baptism of the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches and re-baptized converts upon confession of faith. It was this which resulted in their enemies' calling them Anabaptists; they referred to themselves as "The Brethren".

To explain how they came to be called Mennonites requires a brief reference to the life and work of Menno Simon. He was born in 1496 and was educated for the Church and in due course became a Roman Catholic priest. Observing the staunchness and zeal with which "The Brethren" faced imprisonment, torture, or death for their faith, he felt there must be some basis for their strong conviction and began a thorough study of their teachings. This led to a careful rereading of the scriptures and, finally, to his joining the "Brethren" and soon becoming one of their outstanding leaders. So completely and whole-heartedly did he throw himself into his work, with all its attendant dangers and hardships, that lie shortly became the recognized leader of the whole Anabaptist movement in Holland and northwest Germany, and his fellow religionists came to be known as Mennonites.

Under the rule of the Spanish Catholic Duke of Alva, persecution of the Mennonites in the Netherlands was intensified. They were imprisoned, tortured, drowned, buried alive, and burned at the stake. All told, at least 18,000 lost their lives during this period of persecution. The Martyr's Mirror tells the story of the deep faith, fortitude, and courage of these people and of the unspeakably cruel means employed to stamp out their so-called heresy. Large numbers left the country and sought a haven elsewhere. This was not always easy to find. However, there was a need for good farmers to reclaim the low-lying lands adjacent to the Vistula and Nogat Rivers, and the rulers of this area, many of them Catholic, were willing to be tolerant to these Dutch dissenters who knew how to do it.

Here the Mennonites lived for 250 years, the farmers in villages which they established in the area and the artisans in the city of Danzig. For most of this time, they continued to use the Dutch language in their church services, while in their homes they spoke their Frisian or Flemish dialects, which were similar to the Prussian Low German or Platt Deutsch spoken by the local inhabitants. However, near the end of this long period they discontinued the use of the Dutch language in favour of High German in their churches, and their speech in the homes became more or less identical with that of their Low German-speaking neighbours.

In time, all of the land occupied by the Mennonites fell under the rule of Prussia. As this nation became more powerful and more nationalistically inclined, the Mennonites, never popular with their Lutheran neighbours, were forced to undergo various restrictions. One of the most serious was a regulation prohibiting them from acquiring land. Added to this was the ever-increasing threat of the possibility of being required to serve in the Prussian army. Consequently, when Catherine of Russia, who had heard of their success as farmers and needed colonizers to settle the large stretches of land left uninhabited as a result of her wars with Turkey, sent an invitation to them to come to Russia, a goodly number of the Mennonites decided to accept it.

In 1789, the first group of emigrants, mostly of Flemish persuasion, which consisted mainly of families who had been unable to acquire land because of government restrictions, left Prussia. They established their settlement on the steppes lying on both sides of the Chortitza River, a tributary of the Dnieper. That this group's main reason for leaving was largely economic rather than religious is attested to by the fact that no ministers accompanied it and that for some time they were without any minister to serve them. Conditions in the new land were extremely difficult at first, but the Russian government helped with food and other aid until they were reasonably well-established in their new homes.

Conditions continued to worsen for the Mennonites in Prussia, especially with respect to the military service requirement. As a result another large group left in 1803 to form a second colony. This group passed through the first or old colony to locate on the Molotschna River not far from the Sea of Azov. The members of this group were wealthier and better educated than the Chortitza settlers and also somewhat more liberal in outlook. Being fairly well-to-do and having the experience of the Chortitza settlement to guide them, these newcomers were able to establish a thriving colony in a very short time. They were also favoured by a milder climate and a better soil.

When the settlement at Chortitza became crowded, new areas for settlement had to be located and purchased. The first of these was the Bergthal colony which was set up as a daughter colony of the old colony at Chortitza and consisted of five villages, the largest of which was Bergthal (1836-52). It was located in the Mariepol district south of Chortitza and almost due east of the Molotschna colony. A second daughter colony was established in an area known as the "Fuerstenland", land of the Prince, (1852 and later).

Under the colonial system employed by the Russian government these colonies were largely left to manage their own affairs, secular as well as religious, with what, on the whole, seemed beneficial results. They flourished materially, education gradually improved and cultural interests grew.

However, prosperity and ease may lead to worldliness and selfishness, especially when oppression ceases. In the Molotschna colony there arose a group under the leadership of a certain Klaas Reimer who felt that the church membership, generally, was getting too worldly in its outlook and too lax in its morals and in its adherence to the traditional rules and procedures of the church. This resulted in the formation of a minority church which came to be known as Die Kleine Gemeinde (the small congregation). The descendants of this group will play an important part in our story later, which is the reason for introducing it here.

By 1870, modern progressive trends in the Russian Empire resulted in two movements which did not favour the benevolent paternalism which had up to this point prevailed in the establishment and maintenance of foreign colonies as more or less autonomous and separate communities. The Liberals wanted equal rights for all and the pan-slavic element was not particularly sympathetic towards special privileges for these flourishing Germanic settlements. They advocated establishing a national educational system and national military service from which no one would be excluded.

These new trends caused a good deal of concern to the Mennonites, especially those of more conservative outlook. Various negotiations took place and various attempts were made to make sure that the old privileges would be retained. Some compromises were finally reached, but many Mennonites refused to accept them as satisfactory and started making preparations to come to America. A delegation of twelve was sent out in 1873 to "spy out the land" and to decide on the best place in which to settle. Among other places, they visited Manitoba; but most of the delegates, when they saw the conditions which prevailed here, considered them too harsh and decided in favour of the United States. However, the delegates of the more conservative groups chose Manitoba. They felt that the privileges they asked for would be more permanent under the rule of a monarch than in a republic. They remembered how Catherine had invited them to come to Russia and now in this invitation to come to Canada they saw a parallel situation and felt that history was repeating itself. They did not realize that Queen Victoria might be completely unaware of what was about to happen in this remote part of her empire.

The delegates, Heinrich Wiebe and Jacob Peters, representing the Bergthal colony, and Cornelius Toews and David Klassen, representing the Kleine Gemeinde group, and indirectly the Fuerstenlander who had sent no delegates of their own, saw Manitoba in company with eight others. They visited what was to become the East Reserve on a route that followed closely its eastern boundary. Near the end of the route they came to the home of a settler, Mr. Mack, who had a German wife. Here they stayed for a meal and learned at first hand about the land that was to be their new home. Although they found the mosquitoes almost unbearable and the soil not of the best, they persisted in their determination to make this the new home for themselves and their people.

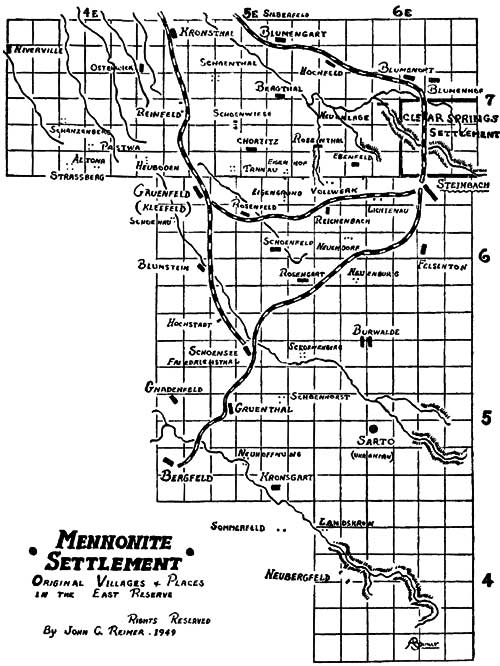

Next year, 1874, the exodus began. Homes and personal effects were sold, sometimes at much below cost. Within two years, all the 500 families living in the five Bergthal villages sold out completely and most of them moved to Manitoba, settling first in the Rat River or East Reserve. The Fuerstenlander, beginning their migration in 1875, settled on the open prairie east of the Pembina Hills just north of the American boundary, which was part of the West Reserve. About half of the Bergthaler, dissatisfied with the poor soil and drainage of the East Reserve, moved west after a few years and established themselves in the unoccupied part of the West Reserve, east of the Fuerstenlander. The Kleine Gemeinde group which was the smallest, some 700 persons in all, established the villages of Blumenort, Blumenhof, Gruenfeld, and Steinbach in the East Reserve and the villages of Rosenhoff and Rosenort on the banks of the Scratching River near Morris.

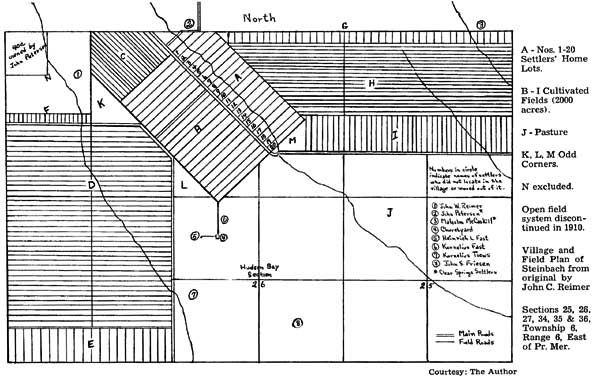

In their manner of settlement and in the management of their affairs, such as local government, fire insurance, and banking, the Mennonites continued as closely as possible the system they had begun to develop in Prussia and had perfected in Russia. Most of the settlers grouped themselves in villages of about twenty to twenty-five families. Usually the village followed the course of a stream, which insured suitable drainage and could provide water for the cattle. The plan of the village of Steinbach was quite typical. A lot of sixteen acres was allotted to each owner (Wirt) for every quarter-section of land owned, six acres were on one side of the road and ten on the other. In time, each owner built a substantial house and barn, joined together, on the yard lot (Feuer Statte) of six acres.

One village in the settlement served as the capital. Here the reeve (Ober Schulze) resided and the books and papers of the settlement were kept. Here also the council, consisting of the headmen or mayors of the villages, met to decide the affairs of the settlement such as the building of roads and ditches, road levies, and other secular matters of general concern. A secretary kept the books and looked after the correspondence.

The church was served by a number of ministers under the leadership and direction of a senior minister known as Der Aelteste, elder or bishop. In addition to presiding at the meetings of the Church Board (Lehrdienst), the bishop was the only minister authorized to administer the rites of communion and baptism. The church in each colony was more or less autonomous. Even though two colonies might belong to the same branch of the Mennonite church they were run separately. However, in Russia, for example, when questions of common concern arose, such as the pending legislation relating to military service, representatives from the various colonies would meet in conference to decide on a common policy.

In the East Reserve there were two distinctly separate churches from the beginning; the Bergthaler, who, having lived in a somewhat isolated colony for a number of years, had developed an outlook and point of view different from any other group; and the Kleine Gemeinder, who had formed a separate church organization shortly after the founding of the Molotschna colony in Russia. Not only had these two groups different views on religion from each other, they also had different backgrounds that went back almost a hundred years to 1789 when the first colony was established in Chortitza. Moreover, most of the Chortitza colonists were originally of Flemish extraction and persuasion while many of the Molotschna were Frisian.

As a result, there was little mixing of the two groups in Manitoba. They lived in separate villages and attended separate church services. In matters of education, the Bergthaler, at least those who stayed in the East Reserve, were inclined to be even more conservative than the Kleine Gemeinde group. In secular matters, however, the whole colony in the East Reserve acted as a unit and the village of Chortitz, a Bergthaler village, served as the capital. Here the records were kept and the secular issues of common concern decided.

When almost half of the Bergthaler moved to the West Reserve they elected a bishop to direct church matters there and had little contact with their brethren in the East Reserve. It soon became evident within the group that moved to the west, that there were a few among them who were much more liberal-minded and progressive than the rest, especially in matters of education and religion. They did not feel that one's religion depended on maintaining old customs, or old styles of clothing, or other minute observances, and they were anxious to learn the language of the land of their adoption. One of the leaders of this group was the newly-elected bishop, Rev. Johann Funk. When he and others of the same mind co-operated with the Manitoba Department of Education to bring in H. H. Ewert from Kansas to become the principal of a Mennonite High School at Gretna and to act as the government inspector of Mennonite schools, a serious rift developed in the Bergthaler church in the West Reserve. The majority broke off, formed a separate church and selected a bishop of their own. This bishop lived in Sommerfeld and consequently this new group came to be known as the Sommerfelder. The remnant that stayed with Bishop Funk retained the name of Bergthaler. Even more conservative than the Sommerfelder were the Fuerstenlander, the first settlers in the West Reserve, who in Manitoba were generally referred to as the Alt Colonier (people from the Old Colony). They refused to have anything to do with the new school or even with any of the Bergthaler. The Bergthaler who had stayed in the East Reserve consisted almost purely of the conservative element. They continued under the leadership of Bishop Gerhard Wiebe, who had originally led them to Canada. They were in close sympathy with the new Sommerfelder in the West Reserve. Bishop Wiebe, himself, was very much upset by the course taken by the progressive Bergthaler and in a pamphlet written a few years later attacked them bitterly for their worldliness and ungodliness. In time his followers came to be known as Chortitzer because he lived in the village of Chortitz.

The Bergthaler under Bishop Funk continued in their progressive views. Eventually, because of some internal disagreement they established a second private school in Altona. Both schools served a very useful function in providing high school education for prospective teachers for the elementary schools, at first only for the West Reserve, but later also for the East Reserve.

After this brief sketch of the origin of the Mennonites and their establishment in Manitoba, it is now my purpose to deal more specifically with the Mennonites who settled Steinbach.

The original settlers of Steinbach were all members of the Kleine Gemeinde Church and Steinbach was the last but one of the six villages founded by the Kleine Gemeinder. People have wondered why such an out of the way place and such swampy and bushy land was chosen for the site. One reason that has been given is that the founding fathers wanted to get as far from any future railway as possible. Another, that they were rather late in getting started and that all the better land had already been taken up. They might have settled in the area immediately south of their co-religionists in Blumenort but for the fact that the English or Scottish settlement of Clear Springs, three miles square, occupied this area. Consequently, they chose a site for their village just south of the boundary of the Clear Springs settlement. The close proximity of this isolated Scottish settlement, already established, may have had quite an important effect on the peculiar nature of the development of Steinbach in the years that followed. Another factor that may have helped to shape this development was the fact that Steinbach was on the edge of the prairie land next to a wooded area which stretched south and east for many miles.

It was in the fall of 1874, that seventeen men, accompanied by their wives and children numbering eighty in all reached the site of the present town of Steinbach and pitched their tents, preparatory to the erection of more permanent shelters. First of all a plan of the village was laid out. The village street was drawn to follow a route almost due southeast, paralleling a creek bed some hundred yards to the left of it. A rectangular block of land consisting of some 320 acres was marked off into twenty sixteen-acre lots, about six acres of which lay on the northeast side of the road and ten on the southwest. The space allowed for the road was ninety-nine feet wide. The lot on the north side of the road was to become the Feuerstelle or homestead, that on the south the Kattstelle. On the Feuerstelle the buildings were to be erected and sufficient room was also allowed for gardens and a small enclosure for cattle. The lots on the south side would later serve as homes for residents that might move in or for the children growing up, and marrying, and continuing to live in the village. In the meantime, it was cultivated by the villagers whose property it had become. Each villager was entitled to as many sixteen-acre lots as he had taken out quarter-sections in the blocks of land assigned to the village. Hence, Klaas Reimer and Franz Kroeker, who had each taken out two, had two lots, the former, numbers 9 and 10 and the latter, 19 and 20.

The shelters erected for the first winter had to be built hastily and varied in form and structure. Most common, perhaps, was a shelter known as a semlin. It was made by digging a rectangular hole three or four feet deep to serve as the lower half of a dwelling sufficiently long and wide to accommodate a family at one end and a few head of stock at the other. To make the walls, sods were piled up to a height of at least three feet above the ground around the edges of the hole. Light was provided by inserting two windows at ground level. Across the sods, poles or rafters were laid close together and covered with earth to serve as a roof. Above this hay might be piled for further warmth. A strong partition was built to shut off an area assigned to the cattle. The interior of the dwelling area was then lined with boards by those who had the money to purchase them in Winnipeg or were able to saw them from logs before the winter set in.

Hay had to be cut for the cattle by hand. Since much of it was frozen before the settlers found time to cut it, it was not very palatable and the cattle gained little nourishment from it. As a result of the lack of food the cattle did not withstand the first winter very well. Many lost ears or horns or tail. Some had to be destroyed because they were so badly frozen. The production of milk under these conditions, of course, was very limited indeed.

Many of the settlers were quite poor and could spend very little money for food. In any case it was hard to obtain. The food for every meal was made mainly of flour and the flour was of very poor quality. Variety in the menu depended on the ingenuity of the housewife in preparing various forms of baking or cooking from this one ingredient. A sort of coffee was made from roasted barley, ground fine.

An interesting account of his early experiences in the founding of Steinbach was given by K. W. Reimer at the celebration of the sixtieth anniversary of this event. In the translation from the German that follows an attempt has been made to retain the homely flavour and simple but terse style of the original.

"We bought the following articles at Duluth - a cookstove, an axe, a ham, and five pounds of lard. Drove by rail to Moorhead and took the Red River steamer from there. Reached Niverville, September 15, 1874. Pitched our tent and spent the night on shore. It rained practically all night. My brother and I found shelter at a half-breed Indian's home. Next morning we set out for the immigrant houses. We stayed there a week. Then our fathers came from Winnipeg with wagons and oxen and we set out for Steinbach. We learned that Canadian oxen stopped for 'ho, ho', (In Russia they had used a similar sounding expression to get the oxen to start).

"When we reached Steinbach each one's lot had been decided upon. On ours stood a large tree. Under it we pitched the tent and tied it to the tree. Then father hung the ham and his watch on the tree and began to build.

"Here was our father with his sick wife, our mother, and eight children between heaven and earth (under the open sky) and winter was at the door. We built the house as follows: First we dug a hole in the earth, thirty feet long, fourteen feet wide, and three feet deep. The sods we piled up at the sides three feet high. Then we put in two small windows just above the level of the earth. Then we went to the bush to get rafters. It is the bush that still stands on John W. Reimer's farm. We had to carry the felled trees out of the bush. Father took the thick end and Abram and I the thin one. The roof of the house was thatched with rushes. Fifteen feet of the roof had boards underneath it, but only rushes covered the rest. (Apparently in their case a gable roof was built: this type of hut was usually referred to as a Serrei). That was for the cattle.

"After this we made a little hay. It was all frozen.

"One evening we were surprised by a prairie fire. To protect ourselves against it we hastily ploughed a strip of land in its path. Many of the sods had to be turned over by hand. However, we were able to save the house.

"That winter our cattle refused to eat the hay because it was too badly frozen. Fortunately, we were able to buy some better hay to save them from starvation. In addition to the hay we gave each ox and cow a slice of bread daily and in this way managed to bring the cattle through the winter.

"Our food throughout the winter consisted of potatoes 'fried' in water, salt, black bread and 'prigs' (roasted barley coffee substitute). For a bag of flour father had to work six days making fence posts. For one load he received a bag of flour.

"In spring, each man began cutting down the light brush and plowing. Those who did not possess two oxen used one ox and a cow. Many people spent their last dollar for seed.

"In 1876, we built a better barn for the cattle, but continued to live in our hut (serrei) for another winter. In the spring of '76 many had lost courage because of the grasshoppers and wondered if they should put in seed for another year. (Grasshoppers had completely destroyed the crop sown in '75). One Sunday my grandparents, uncles and aunts were all gathered at our place. Several of my uncles wanted to move to the States. Then grandmother said, 'We must not do that, for the dear God has heard my prayer. He protected us during the voyage and brought us safely here. We do not want to go farther. Much rather we shall go to work faithfully with God's help and not lose courage. I trust in God, I trust that He will bless us and that we shall have our bread.'

"These words encouraged our parents so much that, filled with new hope, they ordered their seed. A heavy rain on the 24th of May, accompanied by cold weather and snow, killed the eggs laid by the grasshoppers the previous year. They got much rain that summer. In places they had to cut their grain in the water and carry it to a dry spot.

"My father had been a blacksmith in Russia. He needed coals to carry on this occupation here. Then John Peterson came and helped him make charcoal out of green poplar wood. In the years that followed we often had too much water (rain) and the grain drowned out. Often it froze. The roads were bad. A trip to Winnipeg required five days. There were many mosquitoes and many strawberries. In places the main street of Steinbach was so overgrown with scrub and trees that the ox drivers had to walk ahead of the oxen.

"John Peterson and John Carleton (Clear Springs settlers) owned the first threshing machine that was used to thresh the grain in Steinbach. The separator had only two wheels. The power take-off was driven by four pair of oxen. Sometimes the sheaves were frozen together so badly that they had to be cut apart with an axe.

"Our father started a store in 1877. lie had gone to Winnipeg with products of the farm and happened to enter the dry goods store of R. J. Whitla. He asked father whether he would not like to take some goods with him and sell it among our people. He agreed to sell him $300 worth to be paid for later at father's convenience. The chest containing the goods became the counter and it was used as such until the store was built that still stands on Main Street and carries the name 'Central Store' (1934).

"I built my first home in 1885 and sold it in 1887 to John Thiessen for $400 all in $20 gold pieces. My own occupation was that of cheese maker.

In 1889, I built my first cheese factory in Steinbach. In 1892, I built the second in Blumenort and in 1896, the third in Hochfeld. In 1897, the total production of the three factories was 150,000 pounds of cheese. Before I began making cheese I had taken a six months' course in Winnipeg in the making of cheese and butter.

"In 1897, I made cheese for the exhibition and received the first prize - $40.00 cash and a certificate for No. 1 cheese."

After the first year or two the people of Steinbach, like the settlers in the other villages, began building substantial homes. They followed a Frisian pattern of joint house and barn that had been used by the Mennonites in Europe for many generations. In the East Reserve this structure was built by first making a heavy framework that consisted of squared timbers approximately six inches by six inches crossing each other vertically and horizontally at three-foot intervals. The spaces in each frame were blocked in with squared poles of similar dimensions. The chinks were filled in with homemade mortar. Later, many of these buildings were sided with boards, or with shingles, which lent themselves more readily to covering the rather uneven surface. The steep gable roof was thatched during the early years with bundles of rushes, lapped neatly and securely tied in place. The barn section was somewhat wider and higher than the house and was flanked on the side facing the back by a large shed. The barn door led to the backyard and the house door to the front. The ceiling of the house was supported by heavy joists or rafters eight inches deep and four wide, placed some three feet apart. The upper story under the steep gable roof was used for the storage of grain, which had to be carried up very steep stairs in two or three bushel bags.

The house was heated by a large brick stove or furnace so located in the walls separating the living room, bedrooms, and backroom (Hinterstube) that it heated all the main rooms without benefit of forced air ventilation or open doors. It was stoked from the backroom through a large door. In areas where wood was not readily available, hay or straw was used for fuel. Flax straw was especially suitable for the purpose. Above the fire box was a large baking oven which could hold many loaves of bread. Once fired and thoroughly warmed up, this type of stove retained its heat for many hours.

In the first years, a few small windmills were dragged into the East Reserve to grist flour and saw wood. However, in 1877, A. S. Friesen, a man of some means and a great deal of initiative, made use of some heavy logs hauled into Steinbach by men in the employ of Mr. Hespeler to build a large Holland-type windmill. When completed it towered sixty feet into the air and had sails which spread forty-six feet from tip to tip and were five feet wide. The studding for the main tower consisted of eight of the best logs hauled out by Hespeler's men. They were flattened on two sides to receive the siding. Then they were set up in the traditional pyramid style of architecture and covered with siding. The cross braces and other lighter timbers were cut by means of a light saw mill driven by oxen power. The shingles, steel shaftings and bearings, and the mill stones had to be hauled from Winnipeg. The long haul was complicated by seven sloughs in each of which the oxen invariably got stuck. The loads had to be unloaded and carried by manpower out of the slough. In this operation A. S. Friesen, who in addition to his many other talents was the local strong man, came in very handy.

The drive shaft of the mill to which the sails were to be attached was made of four twelve-inch squared oak timbers securely bolted together. Considerable ingenuity was required to devise a method of rounding the ends of this massive beam. Pins were put into each end. By means of these the beam was suspended in a frame. Then a rope was wound around the beam and drawn out by a team of horses thus causing the beam to turn. While it turned the builders used their axes, draw knives and chisels to make a good neck bearing at one end. The wings were firmly screwed to this end and a large wooden wheel, twelve feet in diameter, was bolted to the other. To it were fastened large wooden cogs, and around the wheel were placed wooden brake shoes by means of which it might be stopped or allowed to turn. The cogs on the wooden wheel engaged the cogs of a large iron cog wheel that was attached to a long perpendicular oak shaft that extended to a lower story where it was fastened to a wooden wheel which turned an iron wheel attached to a five-foot upper millstone.

This mill was used to saw wood and to crush feed as well as to make flour. Because the surrounding trees checked the flow of the wind it was found that the mill was not sufficiently dependable to provide all the power needed to meet the demand. Consequently, Mr. Friesen was forced to install a steam engine to serve as an auxiliary source of power when the wind was low. Peter K. Barkman, who had been a mill builder in Russia, was in charge of the construction of the mill and Klaas Reimer, a blacksmith by trade, did the necessary iron work. Barkman's pay was fifty cents per day.

At first, the land surrounding the villages was farmed under the open field system. In this system the arable land was set out in large fields, each of which was divided into strips, varying in size from ten to twenty acres. Every owner in the village was entitled to one strip in each field per quarter-section of land owned. Those who had taken out preemptions as well as homesteads accordingly had two strips in each field instead of one. Crop rotation was practised with an alternation of wheat and feed crops followed every three years or so by summer fallow.

As the years passed, the population of Steinbach slowly increased and it came to be the chief trading village of the area. Its growth continued to be slow until the building of the first all-weather roads in the thirties. At this time a number of activities were begun that considerably increased the cash returns for the people of this community. One was the growing of raspberries. This gave employment to a number of people, many of them children, during the picking season. Trucks came in the morning to pick up the crates of baskets filled with berries and whisk them to Winnipeg where the fruit found a ready market. Another source of income was the growing of potatoes for the early summer market. In time, the producers learned to market their produce in orderly fashion and thus lengthened the period during which the potatoes commanded the early market price. A third development was the feeding of poultry and livestock with balanced-ration feeds. This greatly accelerated poultry and livestock production and resulted as well in the rapid expansion of the production of special feeds by local millers and feed crushers. Furthermore, to meet the rapidly growing demand for poultry chicks several local hatcheries were established and began to thrive.

Advances came also in merchandising. Local merchants, many of whom had their own transportation system, became expert buyers and were able to provide their customers, extending in the course of time far beyond the original Steinbach trading area, with a ready supply of consumer goods at competitive prices.

Local manufacturing enterprises, originally begun with very modest investments, began to grow and expand. This was manifested especially in the establishment of two successful sash and door factories, one of which branched out into manufacturing a variety of products made from wood and also entered into the production of bee supplies, which were sold from coast to coast and even abroad. A machine shop, well equipped with metal lathes and other power tools used in the machining of metal has given expert and faithful service for many years and thus continued the tradition of service and craftmanship brought to Steinbach by the original settlers. A local sheet-metal firm started a foundry and began casting metal for various purposes.

Local automobile agencies and repair shops owned by men like J. R. Friesen, P. T. Loewen, and the Penner Brothers, as well as several others, had established thriving businesses in the forties; some, especially J. R. Friesen, many years earlier. Penner's Electric was ready when rural electrification reached its stride in Manitoba and did wiring in many parts of the province. J. T. Loewen's building-moving firm developed means of moving extremely large buildings safely and economically over large distances and was soon engaged in operations extending far beyond the boundaries of this province. Barkman, more recently, established a concrete plant which produced septic tanks, porch steps, and various other articles made of concrete in large quantity. Other important developments took place in the fields of transportation, earth moving, and construction. A firm, originating in Steinbach, Reimer Transport, operates daily from Edmonton to Montreal, but now has its head office and base depot in Winnipeg.

The Mennonites had always been firm believers in education. They considered it essential that each person should learn to read and write in order to be able to read the Scriptures. However, of those who came to Manitoba few saw any need for education beyond the elementary level. They feared that an education which went much beyond the rudiments of reading, writing, and simple arithmetic could become a threat to their way of life and would undermine their religious faith. Consequently, in Steinbach many years were to elapse before opportunities for higher education were provided. As has been mentioned earlier, in the West Reserve there was a relatively small number of progressive minded Bergthaler who saw the need for higher education, especially for the training of future teachers, almost from the beginning.

Although both the Kleine Gemeinde group and the Chortitzer in the East Reserve continued for many years to hold very conservative views with respect to education, the six Kleine Gemeinde villages, including Steinbach, were more ready to accept provincial grants and, in general, took more interest in maintaining the educational standards they were accustomed to from Russia. From the very first year, the children in Steinbach and indeed in all the villages, Bergthaler (Chortitzer) as well as Kleine Gemeinde, were sent to school. The Board (Lehrdienst) of the Kleine Gemeinde Church drew up a rather interesting set of rules and regulations for the establishment and maintenance of schools that in some respects are not too dissimilar from the regulations in effect in this province today. In the translation that follows an effort has been made to keep as close as possible to the style and content of the original German. In the interests of space some of the less relevant clauses have been omitted or condensed. It reads:

"Because it is necessary that every one in his occupation should be able to read, write, and figure (do arithmetic) every village is required to establish an elementary school (Klein Kinderschule), in which the children, before they are old enough to do regular work or carry on an occupation, are to receive the most essential elements of an education. For this purpose the Church considers it necessary to establish the following regulations:

- The school is under the direction and control of the Church Board (Kirchenvorstand) and its first responsibility is to see to it that a qualified teacher is appointed, who in his moral behaviour will serve as an example to the children entrusted to his care at all times, and who will prevent anything that might lead them astray from finding its way (Einschleichen) into the school.

- The subjects that the teacher is required to teach are, to read correctly, to write, and to do arithmetic, also as time permits, to give instruction in grammar and composition. In addition, singing according to ciphers should be taught in order that, having learned to read music written in ciphers, each one will be able to learn many melodies which he did not have time to learn in school later on himself. However, it is necessary only to learn those melodies which may be found in our Mennonite Hymnal. Part singing we do not consider to be in accord with our standard of simplicity.

- The school may be held either in the community meeting house or in a building specially rented for that purpose. It must in any case be supported by every member of the village community, without exception, regardless of whether he has children of school age or not, since the school is required not only for the children of today, but for all that follow in the future. It is the responsibility of the Board (Vorstand) to see to it that no child is unable to attend because of poverty.

- In view of the fact that some arable land is set aside for the use of supporting the teacher, it is required that such provision and the labour pertaining thereto be divided equally among all the homesteads in the village. The actual cash payment, however, providing the amount is not too high, is to be collected at an equal rate per child.

- The school attendance age for boys is set at 7 to 14 and for girls at 7 to 13. During this age they shall be kept on the school register, and the school fees for each one must be paid regularly. Feeble-minded or otherwise incapacitated children are excluded from this ruling.

- Those who do not live in a village are at liberty to teach their children themselves and are not required to pay to the support of any school or to pay pupil fees. However, a parent that neglects his children and fails to give them the necessary instruction, is duty bound to find some way of bringing them to a village school, in order that they may receive instruction equal to that of the others.

- Instruction shall be given from the first of November till the first of May in every village school, five days a week and from five to six hours daily. Apart from illness or some other valid reason no absence from school will be permitted during the above-named period.

- It is the duty of the school teachers to hold three conferences during the school term, one each, in the months of November, January, and March in order that they may exchange ideas and demonstrate methods. The children are required to be present at each conference.

- Before the end of the school in April a general examination or achievement day (allgemeine Prufung) shall be held by the church leadership (Kirchenvorstand) in every school. The teacher should know a year in advance what his obligations are. In order that this may be so he should be engaged for the next year by the 1st of March. A frequent change of teachers is very harmful to a school. However, if a village hopes to improve a situation by a change, before such a change is made, the Church Board should make a thorough investigation to insure that changes are not made rashly or for trivial reasons.

- The salary is to be paid the teacher in two installments, namely, on the first of January and on the first of April. If for acceptable reasons any parent sends his child for only part of the school term, he is required to pay in proportion only."

The Kleine Gemeinde regulations give a fairly adequate picture of the Mennonite belief in order and system as well as justice and fair play. However, they restrict as well as guide; they serve as a limit as well as a goal and for the first thirty years there was little change in the educational program of the East Reserve or in Steinbach itself. However, the Kleine Gemeinde teachers did try to improve themselves in their knowledge of subject matter and teaching method through attending H. H. Ewert's institutes and teachers' conferences and through private study as well. Most of the Chortitzer teachers, because of the opposition of their church to any innovation or outside influence, failed to do even that. In many cases there was actually a deterioration in the education of the children under their care. Only a few of the teachers who came to Canada from Russia had received a high school education. Others had learned through self-study and experience and had thus improved themselves in their profession. However, busy making a living and overcoming the problems that face all pioneers in a new land, most of the Mennonites had no time to give thought to the need of providing qualified teachers. When their teachers retired or entered more profitable occupations, there were no qualified or even semi-qualified persons to take their places. As a result many of the children received a much poorer education than their parents had had in Russia.

In Steinbach this deterioration did not actually take place. Instead there was a very gradual improvement. In time some geography was taught and by very slow degrees English was introduced into the programme. Steinbach, in company with other Kleine Gemeinde schools accepted government grants and this helped to meet the costs of operation. Government inspectors of Mennonite schools usually reported quite favourably on the conditions they found in Steinbach. After 1900, students from the East Reserve began attending the private schools in Gretna and Altona, and around the years 1910 to 1914 educational progress began to accelerate. The Steinbach teachers made rapid strides in improving their qualifications. J. G. Kornelson, son of veteran Steinbach teacher, G. E. Kornelson, took grade 8 in Gretna in 1911 in three months. Next year, he took grades 9 and 10. Then he took Third Class Normal. In 1914, he took most of grade 11 in Gretna. In 1915-16, he and A. P. Friesen, who had commenced his high school education somewhat earlier, both took grade 12 in Gretna.

Coincident with this rapid improvement in qualifications of the teachers was a rise in the academic level of courses offered in Steinbach. In 1912, a third teacher was added to the staff, a change greatly needed, for enrolment had passed the hundred mark in 1909. Grade 8 was taught for the first time in 1913 with two students enrolled. High school instruction was begun next year, but at first the number of high school students increased slowly. By 1920, it had risen to thirteen out of a total enrolment of 209. In 1923, Grade 11 vas offered for the first time with one student in the class and a total high school enrolment of twenty-eight. A grade 12 class was begun in 1937 and numbered thirteen. The total enrolment at this time was 387 and of this number seventy-three were in the high school. By now, the staff had risen to nine teachers with three, presumably, in the high school. Most of the teachers needed for the East Reserve were now able to get their academic training in Steinbach, and every year a large number of candidates for the teaching profession came from this school.

Shop, Commercial, and Home Economics courses were added to the Steinbach curriculum in the late thirties or early forties. In 1945-1946, these were given in addition to a full matriculation programme. In addition to these extra courses there was a mixed choir, a girls' choir, and a boys' chorus. A school paper was published regularly and there was an annual yearbook. A three-act play was also produced every year. Despite these extra activities the pass rate was high, especially in 1945.

Enrolment continued to rise and reached a total of 572 in 1945-1946, of this number, 131 were in the high school with eighteen in grade 12.

Three of the students in the 1944-1945 classes have since become professors in the University of Manitoba and every year a large percentage of Steinbach Collegiate graduates enter the teaching profession. By 1946, many of the students went on to continue their studies at the University. All of the boys in the 1946 grade 12 obtained degrees in due course at various universities of the United States and Canada. All the girls of this class went directly into teaching after taking a year of professional training. Some continued their studies later and at least one graduated with a BA degree. A grade 12 student of 1947 won the Gold Medal in Science at the University of Manitoba a few years later. A graduate of the grade 12 class of 1945 had the honour of navigating the plane that took Prime Minister St. Laurent around the world.

Education has by now been accepted as desirable and necessary by all the Mennonite churches in the East Reserve and the increase in the academic level and educational achievement has been tremendous as a result.

A few extracts from records of the past:

1888

Present school erected in 1881. Frame, 28 x 24 x 9. Desks for 45 pupils. Each accommodates four. No globe. Blackboard 4 feet by 2'/ feet. Drinking water from well. Separate privies. No trees. School yard one acre. Fenced.

1893

Fifty pupils took arithmetic. Twenty-two took geography. Eighteen took grammar and composition. All took music. Teachers' Institute two days. Blackboard 42 square feet. One visit by inspector, two by trustees, one by clergyman. Number of Public Examinations-one. Teacher had nine years of teaching experience, five in present school.

1901

Six students took geometry and 62 took geography. Two maps in the school. 1907-3 maps. 100 square feet of blackboard.

Grades

1

2

3

4

5

In some subjects the level of work done was considerably higher than the grade indicated.

1902

24

56

18

12

3

1910

49

26

21

18

1899

"It was decided that our teachers spend one hour each day in the teaching of English." (Extract from minutes of Trustee meeting).

Some comparisons of Enrolment:

1947

East Reserve 180 H.S. students; West Reserve 375 H.S. students (estim.).

1961

East Reserve 554 H.S. students; West Reserve 901 H.S. students (estim.)

Lot

Head of Family

No. in Family

1

Klaas Friesen

4

2

Kornelius Fast

6

3

Gerhard Warkentin (came in 1875)

2

4

Heinrich Brandt

5

5

Rev. Jacob Barkman

3

6

Kornelius Goossen

2

7

Jacob S. Friesen

2

8

Abram S. Friesen

5

9

Peter Toews

7

10

Johann R. Reimer

2

11 & 12

Klaas R. Reimer

9

13

Gerhard Giesbrecht

4

14

Johann Wiebe

5

15

Jacob T. Barkman

2

16

Peter Barkman

5

17

Johann S. Friesen

2

18

Heinrich Fast

5

19 & 20

Franz Kröker

5

Total

80

Special acknowledgement is hereby made to Mr. John C. Reimer for permission to use his village and field plan of Steinbach and his map of the Mennonite settlement showing the original sites of the Mennonite villages in the East Reserve.

Page revised: 23 August 2018