MHS Transactions, Series 1, No. 56

Read 25 January 1900

|

Mr. W. G. Fonseca, the writer of the following paper, is a pioneer of the old Red River days. A native of Santa Croix, he was attracted to St. Paul, Minnesota, many years ago, and seeking new scenes, found his way to Red River Settlement in 1859. Here he engaged in business, married one of the Logan family, and settled on Point Douglas, now a part of the City of Winnipeg. Mr. Fonseca has ever been a public-minded citizen, and this paper is a reminiscence of the cart-trail from Fort Garry to St. Cloud, or St. Paul, and return in the days when Winnipeg had not yet come into existence.

The following paper was read in the City Hall, Winnipeg, and before the Historical Society, on the evening of January 25, 1900, in the absence of the writer through sickness, by Mr. K. N. L. Macdonald, a Vice-President of the Society.

“Tempora mutantur” comes to the writer’s lips as he sees today the railways running over the prairies, parallel to the ruts of the Red River cart, and thinks of the slowness and difficulty of travel mingled with a strange romance and interest attaching to the trail and its primitive life, as compared with the present hurry, bustle, and commonplace of the puffing engine and the Pullman car.

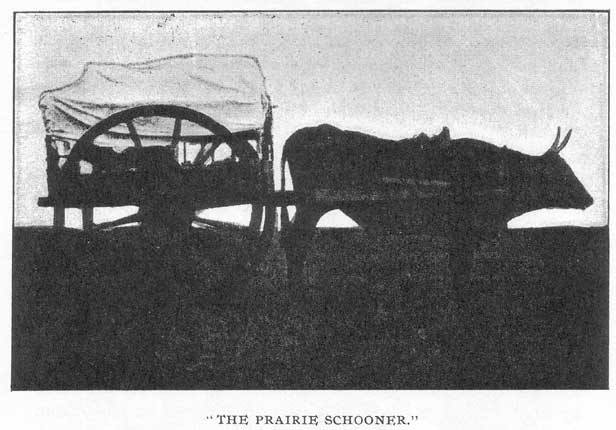

One such journey comes to the writer’s mind, surrounded with more incident than others on which the writer crossed the plains. While in those days supplies still came by way of York Factory, brought by the Hudson’s Bay Company’s ship from Britain, and were carried by bands of hardy voyageurs in York boats by way of lake, river and portage, in the early sixties of the century the cart route over the prairie to St. Paul, Minnesota, was largely availed of by the Red River settlers. The Red River cart - aptly called the “prairie schooner”- took out loads of fur for the Hudson’s Bay Company to St. Paul, and came back laden with supplies for the Company or for the settlers.

For company and safety many carts went on the same expeditions and for days before the start all was activity. As the trip extended over six or eight weeks, it was necessary to be well provided with food. The fare was simple but substantial - flour, strong black tea and sugar were the staples, and the well-known pemmican. Pemmican is now a thing of the past, but was the sheet anchor of the Red River voyageur. Obtained by the buffalo hunters on their buffalo hunts, the flesh of the buffalo was cut up into slices, dried and beaten or flailed into powder; it was then packed in bags of raw hide, into which hot boiling fat and marrow of the buffalo carcass was poured. Thus it became air proof, and without salt or any preservative, the bag closely sewed up, could be thus kept for years. A finer sort of this article, called “berry pemmican,” was made by mixing the flesh with the berries of the abundant saskatoon, or service berry (Amelanchier canadensis). This was considered a delicacy. While some, like the late Bishop McLean, did not appreciate pemmican, he having declared before an audience of notables in London, that eating pemmican was to him like chewing a tallow candle, yet this important staple, worth thousands of pounds a year to the prairie travellers, was so important that the Hudson’s Bay Company could not have carried on its wide and extensive enterprises without it. Supplies for the inner man having been provided, the axe, saw, drawknife, auger and square, needles to sew harness and moccasins are not forgotten, as well as a supply of material for harness. This was of two kinds. First, the “shagganappe,” or prairie cordage, made by cutting the buffalo hide into narrow strips, from one-half to an inch in width; and second, the “babiche,” or narrow strips cut from the deer skin and taking the place of twine. In addition sinews from the back of the buffalo were shredded and spun into what might be called prairie thread. All these have disappeared with the buffalo.

The object of greatest interest in the Red River trippers’ outfit was the Red River cart. Made of tough, well-seasoned wood without a particle of iron about it, it was a marvel of mechanism. It consisted of two rough shafts, called by the settlers trams, twelve feet long, worked out of oak, and with cross-pieces firmly morticed into them. The two outer ones, being about six feet apart, form the foundation. Holes are bored into the upper surface of the trams and two railed pieces are correspondingly bored and fitted upon the rails. Boards are fastened upon the three cross-pieces forming the bottom, and with tail, front and side boards fitted on the body of the cart, it is complete. The great lumbering wheels, consisting of nave, of spokes and felloes, are of oak, rough hewn. The felloes are about five inches wide, the wheel five feet high. They are very much dished, giving greater steadiness to the cart in going on a sidling road. They pass over soft and swampy ground where wagon wheels would almost sink out of sight. The axle is, after the wheel, the most important part and is made of oak. The axle having to bear the weight of the heavy load, requires to be carefully made and then to be well trimmed and adjusted to prevent friction. The axle is lashed to the cart with dampened shagganappe, which shrinks, and so holds it firmly. Five or six of these axles are used up in the course of a trip. They are manufactured as they are needed on the way.

In this cart is placed either an ox or an Indian pony. The harness used for these is the same, consisting of the strips of buffalo hide, the shape of the collar for the ox being a little different from that of the horse, and so arranged that it will not gall the neck of its wearer. The holdback is so adjusted as to enable the beast of burden to hold back in descending a hill. The carts carry from 800 to 1,000 lbs., and require to be filled by a practised packer. Four carts are under the charge of one voyageur, and more than that number are fastened together, the leading rein of the ox or pony being tied to the tail of the cart ahead. The driver is provided with a gun and a supply of ball, powder and shot. As these are always at his hand he becomes a real Nimrod of the plains. It happens, quite often, going over prairie trails, crossing ravines or sloughs, that cart, load, or ox, may be overturned. To the greenhorn on the plains, or as the Indian calls him, “Moonias,” such a disaster seems without remedy. But the skilful voyageur soon spliced his broken trams, replaced his broken railways, and this all done by the ready use of shagganappe, so that the uninjured ox or pony was soon on his way again. The starting of the brigade of carts from Fort Garry, on the Red River, was a great event in the settlement. The first day’s march didn’t exceed eight or ten miles, in order that the beasts of burden might not be overdone at the start.

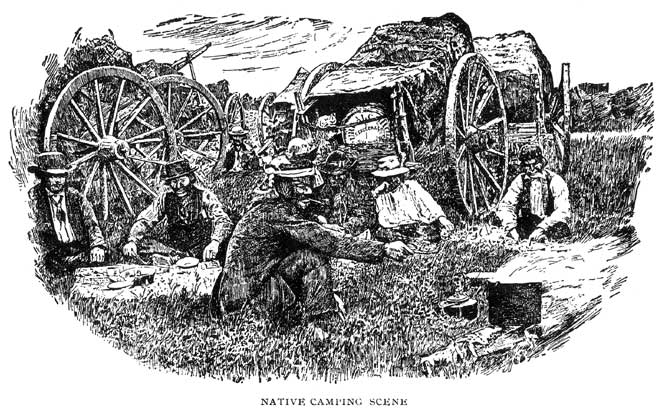

After some hours of steady traveling, as the sun stood high in the sky, the welcome stop took place. This was made by some stream or lake. The oxen and horses let loose from their burden, bounded away to the water, into which they plunged neck deep, remaining there safe from the tormenting flies and mosquitoes, until hunger drove them to the pasture awaiting them. The voyageurs at once struck their camp. With the party were a number of women and children, and at once a fire was lit, and the kettle was soon simmering. While this was occurring the Red River bannock was in course of preparation. It was simply flour, water and salt. The dough was kneaded on a bag spread out on a buffalo skin, the cakes were flattened and baked in a frying pan over the fire, and were soon ready. When the water had boiled in the kettle, the pemmican bag was broached, a quantity of it was stirred into the boiling water, flour and salt were added, and thus resulted the celebrated “rubaboo,” as it was called. When the mixture was thickened it then was called “rowscho,” but for the journey the former was preferable. Hot bannocks and piping hot “rubaboo” were served around, the latter in cups, and the tea in tin cups soon began to disappear among the hungry company. The appetite stimulated by fresh air and exercise was surprising, and a dyspeptic being looking on at such a meal would turn green with envy.

One day our midday camp was struck just beyond the crossing of the Big Salt River. We were just ready for lunch when a democrat wagon hove in sight containing a coal-black Sambo as driver, and three gentlemen. As they approached they looked long and enquiringly on the camping scene, with its grazing animals, carts, and a company of swarthy natives, in the middle of a vast prairie. On calling over on them, I found a distinguished party, consisting of Hon. Joseph Howe, Secretary of State for the Dominion of Canada, which was then talking of annexing the Red River Settlement, Mr. W. E. Sanford, of Hamilton, Ont., afterwards Senator, and Mr. William McGregor, of Windsor, since that time a member of the Canadian House of Commons. I invited the party to lunch with me; fortunately we had bear steak, and pemmican in its two-fold messes. Curiosity, more than lunch, induced an acceptance. I carried a bottle of very old St. Croix rum, so far as I was concerned for the stomach’s sake, not the palate. At the sight of the amber fluid the Hon. Mr. Howe clapped his hands, and turning to Mr. Sanford, exclaimed, “Sanford, there is corn in Egypt,” which they tested heartily. This trip of Mr. Howe to Fort Garry was the one, which Mr. McDougall accused him in Parliament of undertaking to prejudice the settlers against him. Mr. Howe plied me with questions touching affairs at the Settlement. The party proceeded northward, we south. Scarcely two hours had passed when the democrat returned. By an accident Mr. Sanford’s gun had gone off and lodged its contents in the calf of McGregor’s leg.

Two hours was usually enough for the midday camp, but if the day was hot a longer time was allowed. When the camp was struck the capture of oxen and ponies was always exciting. Knowing their advantage, they played a good game of hide and seek, and were coy to the advances of their masters. Sometimes to drive the refractory animals among the carts was a last resort. At such times the hot nature of the voyageur was apt to get the better of him.

When the start had taken place many an incident was sure to follow. Without bridges, ferry, or a boat, a heavily loaded train has serious difficulty in crossing streams. A heavy fall of rain may change fordable streams into booming rivers. In such cases a boat was improvised, from materials on hand. Four cart wheels were taken and placed dish upwards and the four points of contact securely fastened together. On the outer rims four pieces of wood were lashed, forming a square. Meanwhile six buffalo hides were soaked, when sufficiently soft sewed together, and spread out, upon which the frame work was placed. The edges were brought up and laced to the outer bars, one line fastened to the stern, another at the bow. A party would then swim across, carrying the bow line over; the boat was launched, and floated like a duck, with a capacity of 800 lbs. The whole transportation was accomplished, amidst a cloud of mosquitoes, sand flies, and all prairie annoyances, including mud. It was during this work one heard untranslatable language, as accident and adventure took place at the crossing.

Even when the crossing of streams was not so serious there was always the possibility of upset and disaster. Coming to the steep bank of a river to be crossed, a line was tied to the middle of the axle of the cart, and a turn of the line made around the trunk of a tree on the bank. Thus the ox and cart was led gradually down the deep decline until the water was reached. On the opposite bank corresponding arrangements were made to haul them up from the bed of the stream.

The afternoon journey was usually continued for about twelve or fifteen miles, when the cheerful word, both to man and beast, was given to halt for the night. The cuisine was again put into operation, though the menu was somewhat changed. Instead of rubaboo, “re-chaud” was served, commonly corrupted “row-scho,” from the Latin re and French chaud, to heat over. Pemmican cooked in a frying-pan, a little grease, pepper, salt, with a trace of onions and potatoes added, constituted this, a dish to set before a king. If the night was clear, and the moon flooded the prairie with her silver light, robes were spread. The sound of the fiddle invited the dance. The Red River jig was struck up, and one after another exercised himself to his heart’s content, as the shouts of the audience stimulated him. Amidst peals of laughter and snatches of voyageurs’ song dull care was forever banished from the camping ground, and you were compelled to acknowledge that the voyageur is “a fellow of infinite humor.” But the best of company must part. Wrapped in robes and blankets each sought to put himself at rest. The music of the spheres was rudely silenced by an appalling outburst of nasal energy, a pandemonium of discordant notes fills the air happily “sweet oblivion ” came to the most wakeful and he too may add his note to the general discord. Thus the day ended.

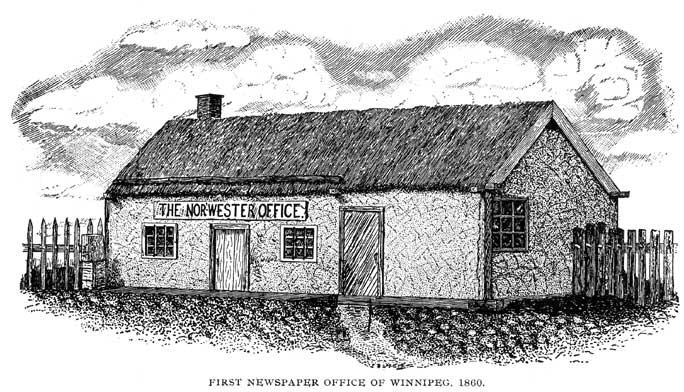

My return trip from St. Paul in 1869 happened to be one of considerable importance. Canada had acquired Ruperts Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, but the formal transfer had not been made. Hon. William Macdougall had been named as governor of the Northwest, and he had come by way of St. Paul in the autumn of 1869 to enter on his duties so soon as the formalities should be arranged. In the meantime Louis Riel, Jr., and the French half-breeds had risen in rebellion and seized the main highway along the Red River leading to Fort Garry. The story of this rebellion is beyond our scope. For years agitation against the Hudson’s Bay Company had been going on in Red River: The Nor’Wester, the only newspaper of Red River, had been begun in 1860 by Messrs. Buckingham & Coldwell, and from this centre the spirit of dissatisfaction spread. The so-called governor was on his way. Mr. McDougall came from St. Paul through Minnesota and Dakota, along the usual trail. I had seen him and his party by the way and now the boundary line of 49° was being approached.

Nearing Pembina, the governor expectant, family and suite give us the go-by. The glossy blacks cross the line ahead of us. The coming members of the to-be new government make home within the historic enclosure of the H. B. Co.’s post October 18th. On the 19th I set out, leaving the train behind. I had four passengers with me, Dr. O., D., madame and two children. Arriving opposite the house of a friendly half-breed, he signaled me to stop, beckoning with his hand. I entered his house. When he had cautiously closed the door, he enquired, seemingly with much interest, “Where are the carts?” Continuing, he said, “They have seized McKay’s train at St. Norbert and are on the qui vive for yours.” My train was loaded with the government household furniture and supplies. “You see monseigneur, they think McDongall is bringing guns, powder and balls to fight the Metis. You will find a barricade across the road, all Canadians are turned back, and to-morrow twenty men will be here to turn McDougall and his men back to Canada.” My democrat being covered with white cotton, would no doubt be an object of suspicion, indicating the arrival of strangers. Communicating what I had heard to the Doctor and madame, doubt and uncertainty flitted like a cloud across their otherwise cheery countenances. We found Pembina in a state of jubilant expectancy. The war muse had inspired a composition of verses in the style of the Marseillaise, which were scattered broadcast. I secured a copy.

Next morning, the 20th, I called on Mr. McDougall. Felt it my duty to inform him what had been communicated me. Handed the martial verses to him in which he figured, volunteered some advice respecting the government’s goods. I was quite convinced that the train would be seized. Such portion of it as carried my own goods gave me no concern. It also carried a number of trunks belonging to Captain and Mrs. Cameron. If those should share the impending fate I feared grave consequences would ensue, which were afterwards realized.

I supposed that I had made my report to a sensible and judicious gentleman, but was egregiously mistaken, as the sequel will show. In my good offices the governor-expectant interpreted treachery, as stated in one of his North-West reports; he writes: “The person in charge of the government train called upon me and gave me such information as convinces me that if he is not in the pay, he is in the confidence of the insurgents.” Mr. McDougall rose from his seat, drew himself up to his full height and struck an imposing attitude, as with outstretched arm and rigid finger, he ordered the train to proceed on the Queen’s highway, declaring that he would see that no half-breed dare molest it. That was the last he ever saw of the train or its elegant freight. The melodrama of the Big I and Little U ended, I bowed myself out, regretting “Love’s Labor Lost.”

In rolled the carts, thirty-six in number. The men were anxious to get home, it being very late in the season, especially Modeste Lagimodière, a cousin of the late Louis Riel. Before leaving Pembina I secured a cap, capote, belt and a pair of moccasins for future emergency, should it arise. This day, the 20th, we were to meet twenty armed men. Upon Governor McDougall’s arrival at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s post, Mr. Provencher was despatched to Fort Garry to prepare the way for the governmental party. But he was not allowed to pass the barricade. Captain Cameron being an officer of Her Majesty’s Royal Artillery, supposing that he would meet with no opposition, although advised not to proceed until there was an assurance of success, set out. The barricade was guarded by a strong band of armed men. Jehu-like, the captain drove his chariot against the obstruction as though he would crush all opposition in his way, but, unfortunately, it stood the shock. Angered at this humiliation, the order rang out, “Remove that blasted fence,” which has since passed into a proverb. French admiration of gallantry found expression on the other side of the barricade. Inexorable, however, are the orders. The captain, unharmed, is turned from the promised land, but the agents of the audacious Riel are as deaf to threats as to reason. Resistance would amount to foolhardiness. The man Lucien, one of the guards, is a Hercules. His enormous strength is irresistible. I saw him, when on a return trip from St. Paul, place a barrel of alcohol containing forty gallons, on his shoulder without assistance, cross a submerged bridge when the pathway of logs were afloat on the stringers, requiring prodigious strength, and repeat the feat six times.

In the meanwhile we bade adieu to Pembina, and we were on our way to the barricade. The order of march was as follows: First, the white covered democrat, next a Red River cart carrying our camping outfit, driven by a half breed boy; a saddled pony followed. Being on the lookout, when about twelve miles from Pembina, I discovered a dark line away on the horizon, and as I felt sure there were the twenty men on their way to give Mr. McDougall a surprise, I ordered a halt. Then looking the doctor full in the face, I said, “There they come!” A quiver passed over his features. Madame’s cheeks blanched slightly. I confess I felt some concern myself. I gave the doctor to understand we had no time to lose. Pointing in the direction they were coming, “See, the cavalcade is advancing rapidly; we are already observed!” The reflection of our white covered vehicle cannot escape those keen-sighted hunters even at this distance. “What is to be done?’ inquired the doctor. “Be sure you throw off all reserve, be friendly, shake each heartily by the collar,” interrupted the doctor. “This is no time for jokes, sir; action, action. I am sorry to announce that your much-cherished Dundrearys must be sacrificed to the god of necessity.” This was a stunning blow. They were to be envied. Requesting him to step out, madame handed me a pair of dull scissors. Those black, wavy, silken, flowing, magnificent whiskers, the pride of manhood, the object of careful shaping and culture, the flag nature had stuck to the mast, had now to be lowered. The tonsorial operation began, and perceptibly a moisture gathered in the corners of the victim’s eyes. Was it want of skill, or an altered presence? Sentimentalism just now, however, was out of place. The horsemen are approaching. The Capote is brought into requisition. It fits well. Cap, belt and moccasins are all arranged: The metamorphosis is complete. It was then arranged that the doctor would drive the cart, the boy ride the pony, and I manage the democrat. So we proceeded to meet the rapidly approaching band. They deployed across the road, and in less than one-half hour our progress was arrested, we were face to face with a squad of twenty armed and well-mounted men.

They presented an imposing scene on the lonely prairie. I recognized Le Pierrie, Pierre Lavallee and others, all picked men. Alighting from the democrat, the transformed son of Aesculapius doing the same, I met with a gracious reception, which was acknowledged by the process of clasping and shaking twenty hands. As I approached, each man lifted his cap. There is an innate characteristic politeness about these Metis which the rude nomadic life they lead cannot eradicate.

In the intensity of my exertion I gave the metamorphosed gentleman a side glance, and was gratified to find him throwing heart and soul into his shake.

As soon as opportunity offered, I asked: “Where are you going, gentlemen?” “To Pembina.” “You must be on very important business.” “Yes. Sent by the provisional government to turn Mr. McDougall and company back.” “At this season? Impossible! He has women and children with him.” “Such are our orders.” “Before doing so, ask him to explain his position.” “Very well - but our orders are strict.” The distinguished manners of the doctor and his home-like appearance attracted considerable attention. Lavallee rode up to me, and exhibiting a rare delicacy, bending low down, asked in almost a whisper, “Who is this gentleman?”

“A friend I am taking to the settlement. He is a good doctor and will be useful to us. Do you think, Mons. Lavallee, I can pass him and family through?” “Oui, oui, Mons. Riel is very particular.” “Prenez garde,” cautioned the captain of cavalry. “Pickets are posted along the line of road, you will not see them, but you will be seen.”

The restiveness of their well fed steeds broke off further interview. Bowing adieux, amidst the goodwill expressed, bon voyage from twenty voices, which we heartily echoed back, their horse’s bounded away under the stimulating effects of whip and spur. A short time placed the cabaleros beyond hearing. We mutually congratulated each other, upon the safe crossing of Rubicon number one. Madame insisted that to her presence success was due. The doctor was equally positive that his equipment was all potent. What of myself? I meekly nodded assent to Madame’s views, and expressed a hope that the inspiration, from whatever source, would see us through.

Towards evening the dreaded barricade hove in sight, which we found, by close inspection, was guarded by about 150 armed men. That formidable obstruction, “That Blasted Fence,” that closed sesame which had defied entrance to a gallant officer and a plenipotentiary, and had so far kept Canada out in the cold! Could we have hoped that these poles would yield to any charms we might possess?

Approaching the obstruction with less address than had been done by others in the face of Riel’s swarthy soldiers, we were immediately surrounded. Then began a second enactment of hand-shaking and a general fraternizing, during which the doctor achieved a brilliant triumph. An aged veteran, Captain Landry, approached, demanded where we were going; we having respectfully asked to be allowed to pass, the bars were immediately set aside and we were on the other side of Jordan. Bowing our thanks, a movement was made forward. The veteran instantly waved his sword, which intimated “not so fast,” strangers were not allowed to go unchallenged. Was “Paradise lost?” Captain Landry explained in polite French that the provincial government, which assembled at St. Norbert, compelled to take us for examination. If I had not been present the party would have been turned back. A guard stepped forward, took hold of the bridle, led the way down a narrow avenue flanked on each side by tall poplars. We should have seen something romantic in the surroundings under different circumstances. To add to the gloom which had begun to overshadow us, a cold, cheerless rain began to fall; the air became chilly and raw, there was a dismal look about things.

The gloom was instantly dispelled on reaching the rectory. Father Ritchot, a burly, brusque gentleman, a Chesterfield in manners, received us most graciously, and we were treated to an excellent tea. In due time we reached Fort Garry and home.

A cordial vote of thanks to Mr. Fonseca was moved by Dr. Bryce, seconded by W. J. McLean and unanimously carried. After other business the meeting adjourned.

Page revised: 28 October 2014