MHS Transactions, Series 1, No. 65

Read 9 February 1904

|

The following paper on rare Manitoba birds was read to the Historical and Scientific society of Manitoba on Feb. 9 by George E. Atkinson, naturalist, a member of the society:

In presenting to the scientific world any series of new or unusual records we must always base our claims for their rarity within the district in question upon the previously published records of that district, and for that reason the proof which I have to produce, viz.: That the: published records of Manitoba birds to date have not included these species herein claimed as new to the Manitoba lists nor referred to the other color phases described as usual within the district, is possibly the strongest which could be produced no matter what subsequent critics may say: In speaking of unusual records I have included new records, or those made for the first time within the district, last records or the last record of disappearing species. Records of increase, or those records of certain species which have found conditions favorable and adapted themselves to and increased in numbers within the district, and a few unusual color phases, giving a few examples of the eccentric changes of plumage found among some birds as a result of certain causes. The material has been somewhat systematically arranged and the species under description are dealt with entirely from the scientific point of view. The species referred to have all come under my own personal notice in the course of my business in Manitoba since Jan. 1897, a period of about seven years, and I have not made any attempt to use the records of others which I have not had personal experience with and all records herein made can at any time be authenticated in the majority of cases with the individual speciment.

Various reasons may be given for the occurrence of these birds among us. Some species becoming crowded within certain districts are constantly extending their ranges, and with conditions favorable, will add themselves to our regular list. Others, however, having reached us as a result of having for some reason or other wandered for a very long distance out of their course during migration may be safely classed as accidentals and there is little probability of their ever becoming other than this. And all these species have been referred to under their proper heads as to cause of their appearance in the province. One thing I think that when a species accidentally arrives among us from any cause, and begins to breed, they may thereafter be included upon the list of our regular species, but where an individual reaches us without a mate there is little possibility of that species being more than an accidental. Of species breeding north and wintering south of us with more or less erratic migrating habits we can never be sure when nor in what numbers they may reach us in their travels and one may wait a life time without a sight of them.

In October of 1902, Mr. Moore, of this city, a well-known bird lover, was called by a local taxidermist to identify a strange bird. The species proved too much for him and he applied to me for the information. His description was not the most definite and I asked him to get the bird, which he did, and I at once recognized it as an immature Longtailed Jaeger, wing measurement 12 ½ inches, tail 8 ½ inches. I also secured the information that it had been collected by one Capt. Fellows, an English gentleman, while shooting at Clandeboye marsh on Oct. 8. A few weeks subsequent to this a note in the Free Press announced the capture of a second specimen in the Northwest Territories. As this species is a bird of powerful and long-sustained flight, breeds in the Artics and winters in the Gulf of Mexico, it is easily understood how these two birds might have wandered overland with migrating gulls though authorities unite in stating; that they seldom travel overland, usually following the seacoasts.

I know of nothing of striking interest in the Jaeger save that they are an overbearing group of the gull family and wherever found try to act the boss of the gull colony.

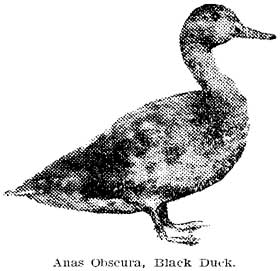

During the first few years of my residence in Manitoba I was given to understand by sportsmen and others familiar with the birds that the black mallard as they are called it was not found in Manitoba at all. I failed to note its presence anywhere I was collecting. Winnipeg taxidermists stated that the bird was extremely rare in the west, and my first authentic record is that made by Mr. F. G. Simpson of this city, who collected a fine male bird at Clandeboye marsh, south of Lake Manitoba on Oct. 28, 1900. The bird when brought to me had been very poorly preserved, and being left in this condition for nearly two years it was impossible to make anything but a record of it. Early in September, 1902, a female bird was received from Delta, where it was collected by W. Burr on Sept. 4. In Oct. of the same year John Atkinson, of St. Mark's, collected two specimens, one of which, a very fine male bird, was received by myself. While a flock of five birds were seen on the same marsh by several parties that fall. In, September, 1903, I received another specimen from Mr. Burr, of Delta, and heard of several other records that fall, and from it conclude that the black Cluck has now gained a footing in the Manitoba marshes, land finding conditions favorable will increase and become one of our most abundant and riot the least acceptable game birds in the future.

During the first few years of my residence in Manitoba I was given to understand by sportsmen and others familiar with the birds that the black mallard as they are called it was not found in Manitoba at all. I failed to note its presence anywhere I was collecting. Winnipeg taxidermists stated that the bird was extremely rare in the west, and my first authentic record is that made by Mr. F. G. Simpson of this city, who collected a fine male bird at Clandeboye marsh, south of Lake Manitoba on Oct. 28, 1900. The bird when brought to me had been very poorly preserved, and being left in this condition for nearly two years it was impossible to make anything but a record of it. Early in September, 1902, a female bird was received from Delta, where it was collected by W. Burr on Sept. 4. In Oct. of the same year John Atkinson, of St. Mark's, collected two specimens, one of which, a very fine male bird, was received by myself. While a flock of five birds were seen on the same marsh by several parties that fall. In, September, 1903, I received another specimen from Mr. Burr, of Delta, and heard of several other records that fall, and from it conclude that the black Cluck has now gained a footing in the Manitoba marshes, land finding conditions favorable will increase and become one of our most abundant and riot the least acceptable game birds in the future.

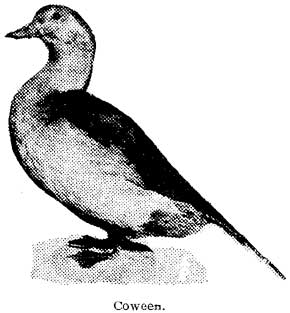

On Oct. 19, 1899, the only specimen of this species I have heard recorded for Manitoba was collected at Whitehead lake, southern Manitoba, by Mr. H. W. O. Boger, of Brandon. The bird was sent me for identification and preservation, and proved to be a young male with a very poorly developed plumage and a single long tail feather. It was travelling with a flock of lesser scaup ducks when noted as a stranger and taken in for keeps. This species is a very common saltwater bird, moving south in the early winter and remaining in immense numbers in the open water of the great lakes all winter. They feed upon small fish, mollusks and crustaceans. They are expert divers and frequently descend considerable distances below the surface to secure food. The flesh is coarse, black and fishy, and is therefore seldom accepted as an edible species. The chief line of migration is the sea-coast, while the principal overland route is directly from James Bay to the Great lakes where they winter and remain until late in April. How this specimen had managed to wander so far out of the course is difficult to say, except that he left his own species long before they had thought of migrating and took up the company of the bluebills on their southern journey. The coween will never be a numerous form in Manitoba because of the long overland journey to our Manitoba lakes, and they are so late in migrating that all local water is frozen over before they could reach us. The mature bird is a beautifully marked species, but beyond this there would be little gain at his addition to our regular bird list.

On Oct. 19, 1899, the only specimen of this species I have heard recorded for Manitoba was collected at Whitehead lake, southern Manitoba, by Mr. H. W. O. Boger, of Brandon. The bird was sent me for identification and preservation, and proved to be a young male with a very poorly developed plumage and a single long tail feather. It was travelling with a flock of lesser scaup ducks when noted as a stranger and taken in for keeps. This species is a very common saltwater bird, moving south in the early winter and remaining in immense numbers in the open water of the great lakes all winter. They feed upon small fish, mollusks and crustaceans. They are expert divers and frequently descend considerable distances below the surface to secure food. The flesh is coarse, black and fishy, and is therefore seldom accepted as an edible species. The chief line of migration is the sea-coast, while the principal overland route is directly from James Bay to the Great lakes where they winter and remain until late in April. How this specimen had managed to wander so far out of the course is difficult to say, except that he left his own species long before they had thought of migrating and took up the company of the bluebills on their southern journey. The coween will never be a numerous form in Manitoba because of the long overland journey to our Manitoba lakes, and they are so late in migrating that all local water is frozen over before they could reach us. The mature bird is a beautifully marked species, but beyond this there would be little gain at his addition to our regular bird list.

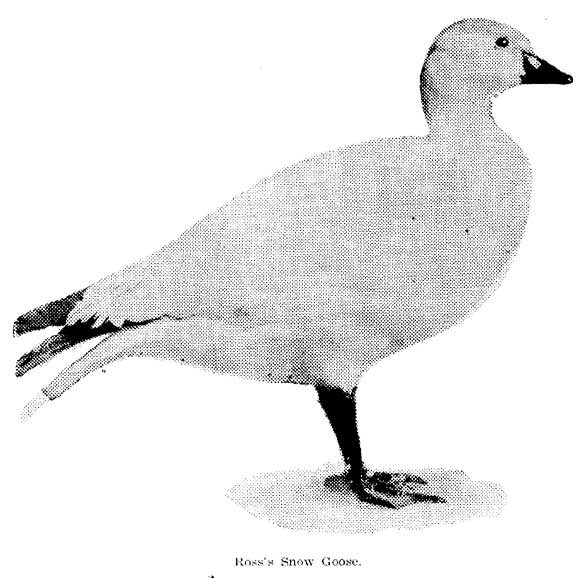

On Sept. 20, 1902, a young lad, F. Marwood, who was working for me, secured a rare specimen under peculiar conditions. He had been paddling on the Red river with a companion above the city, and saw a. small white goose sitting on the bank. Having only a small rifle with him he failed to secure it after a few shots and the bird flow off. On their return toward the city they again discovered the bird on the bank when one of them alighted and secured it. Thinking if but a common snow goose he took it home, skinned and eat it, saving the skin to mount. Before he did this, however, the mice discovered it and destroyed half of the head and neck. Upon examination of the bird after he had mounted it, discovered to me a Ross's goose, and I remounted it and managed to patch it up so as to make one side presentable enough to photo graph. I endeavored to secure this specimen but the inflated mercenary ideas of the owner placed it beyond my reach and careless preserving in the first place, and subsequent careless handling almost destroyed the bird and I believe it fell into the hands of a local taxidermist, who is impressed rather with its commercial than its scientific value, and may therefore be practically considered a lost record save for these notes. I subsequently heard that in 1901 two other specimens had been received at the old Grieve establishment, but had been Spoiled before being preserved and no data could be secured. During the fall of 1902, Mr. John Atkinson of St. Marks, informed me that he had on two other occasions seen a flock of five of these small white geese hanging about the Clandeboye marsh but he had thought them young wavies, and had not bothered them, so that we have hopes of yet securing a good specimen of Ross's goose, which will remain a permanent record of the spieces for the province. They are a bird which ranges in the western Territories, but is nowhere very common, and the presence of the bird in question at that time is unexplainable, as the other geese had not begun to move southward at all. It was in a good healthy condition, but had previously been shot at, and had a leg broken, which accounted for its disinclination to fly when disturbed on the river bank. In size the body of the bird is about that of a large mallard.

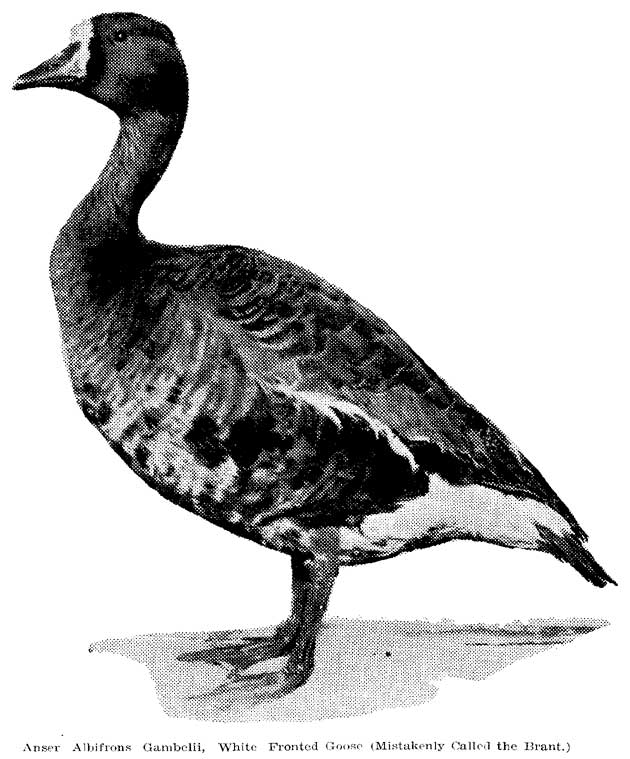

I have been pointedly contradicted by those local authorities of indifferent calibre when I stated that the Brant goose was not found with any regularity in Manitoba, but notwithstanding statements to the contrary I repeat that, as specimens are not forthcoming to prove records, this bird is of very rare occurrence in the province. In explanation I may state, however, that I find many sportsmen, who should know better, regularly call the white-fronted goose the Brant, and this accounts for their claims that the Brant is numerous in some localities. The only record I am able to authentically locate is the specimen in my collection, which was taken by an Indian at Oak Lake in the spring of 1889, and being recognized as a rarity, was mounted by himself and subsequently secured by the late Geo. Grieve from whom I secured it in April, 1901. Because of similarity in size it might in the distance be confused with Hutchin's goose, but as the Brant is chiefly a bird of the sea coast it is unlikely that it will ever become more than an accidental visitor to us.

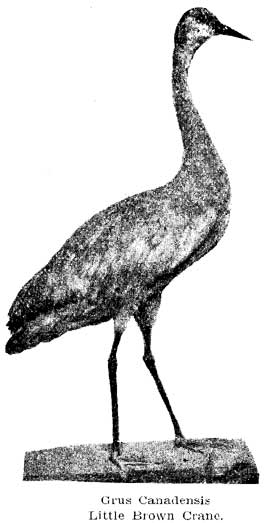

On May 6, 1898, a man came into my store at Portage la Prairie and asked me if I wished to purchase a wild turkey. I was for a time puzzled to know whether he desired to sell a turkey vulture or a crane, as both these birds are frequently called wild turkeys in this country. I instructed him to bring the bird in until I could examine it, and I was much interested to find he had brought a little brown crane. He informed me that he had secured it on the preceding day a few miles northwest of town out of a flock of five of the same sized birds. The bird proved, on examination, to be a mature male brown crane and so far as I was able to learn was the first and only specimen reported for Manitoba and I did not hear of any further records until about the beginning of October, 1903 when a gentleman brought in what proved to be a second specimen. This bird was alive and had been caught by a single toe in a trap on his farm near Morris, Man., directly south of Winnipeg. He stated that there was a large flock of them, but could not say not they were all the same size. As the immature of this species and of a G. mexicana, the sandhill crane, are very much alike I did not decide as to its identity until after trying for two weeks to tame and feed it. It obstinately refused all attempts to tame it, and all food, however or whenever offered and finally died in its wildness, and I subsequently discovered it to be a mature brown crane. The chief points of difference between these species is the much smaller size and the entirely feathered head of canadensis, the head of mexicana being unfeathered, of a reddish brown color, and covered with a growth of short, black hair.

The range of the brown crane is more western, but as it breeds from the Mackenzie river region to Texas it is possible that it is of more frequent occurrence in Manitoba than has been generally supposed. In fact Prof. Macoun, of the geological survey, Ottawa, says he is of opinion that the species has been overlooked in previously published lists and that many of the cranes described under G. mexicana are really G. canadensis. The difference is so great as to be conspicuous and unlikely to be overlooked, if species were known in life.

Comparative bill and tarsus measurements show much difference. In G. mexicana they are: Bill, 5 to 5 ½ inches, according to age: tarsus. 8 ½ to 10 inches. G. canadensis Bill, 3 inches. Tarsus 6 ½ to 7 ½ inches, according to age.

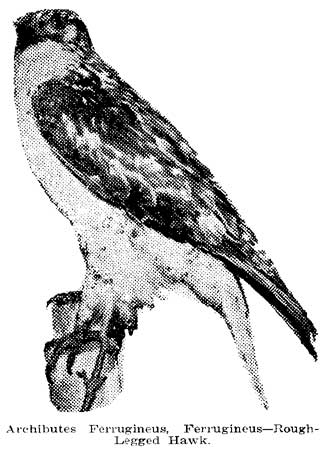

As this species which is commonly known as the squirrel hawk ranges west and south of the province; it is not surprising that it might occasionally wander over the border line, but the specimen exhibited, a female bird is the first I find recorded within our lines and it was collected some nine miles due north of Portage la Prairie, or nearly the centre of Manitoba, on May 6, 1898. While at first sight they would appear to be a very powerful and dangerous hawk, investigation discovers in the weak claws and general slender build, a friend rather than an enemy, as the food of such species consists in the main of gophers, mice and other agricultural vermin. Within their own range they are most persistent in their persecution of the prairie dogs and spermophiles which work such havoc with growing grains and shrubbery. For this reason the ferruginous rough-legged hawk would be a welcome addition to our local list of birds of prey.

On June 2, 1897 I received a pair of burrowing owls which were collected about five miles north of Portage la Prairie. I was unable to locate the species on any previous list of provincial birds, and wrote to the Washington agricultural bureau and the Smithsonian institution, about them and received replies that no record had been received of the burrowing owl in Manitoba. In the spring of 1900 another specimen was secured near the same point and each season an individual specimen has been collected and others observed in the same vicinity. On May 9, 1902 a specimen was collected near Grant's Lake, north of Rosser, and last spring, May, 1903, another specimen from near the same locality, and one from Portage la Prairie were received. So that we may conclude that the species has become permanent and will, with protection and favorable conditions increase. In the west this is a very abundant species of which tradition speaks as living a life of harmony with rattle snakes mid prairie dogs, but tradition's harmony is not as sublime or idealistic as many suppose since the most supreme harmony prevails after dogs, snakes and owls are inside. That is the dogs in the snakes, the snakes in the owls and the owls comfortably at home in the burrow of the squirrel, because as elsewhere stated, the rattle snake preys upon the dogs old and young, and the owl in turn kills and eats both dug and snake and occupies the burrow as a nesting site. The numbers of the species in Manitoba will be somewhat restricted for a time because of the fact that very few of the burrows of our large grey spermophyle are large enough for a burrow for the owl and he has to hunt about until larger and quarters are available. But as I have stated in a previous pamphlet, he would he a welcome addition to our list of birds of prey because of his expert knowledge of gopher and spermophyle capture and his huge capacity for this class of food.

On June 2, 1897 I received a pair of burrowing owls which were collected about five miles north of Portage la Prairie. I was unable to locate the species on any previous list of provincial birds, and wrote to the Washington agricultural bureau and the Smithsonian institution, about them and received replies that no record had been received of the burrowing owl in Manitoba. In the spring of 1900 another specimen was secured near the same point and each season an individual specimen has been collected and others observed in the same vicinity. On May 9, 1902 a specimen was collected near Grant's Lake, north of Rosser, and last spring, May, 1903, another specimen from near the same locality, and one from Portage la Prairie were received. So that we may conclude that the species has become permanent and will, with protection and favorable conditions increase. In the west this is a very abundant species of which tradition speaks as living a life of harmony with rattle snakes mid prairie dogs, but tradition's harmony is not as sublime or idealistic as many suppose since the most supreme harmony prevails after dogs, snakes and owls are inside. That is the dogs in the snakes, the snakes in the owls and the owls comfortably at home in the burrow of the squirrel, because as elsewhere stated, the rattle snake preys upon the dogs old and young, and the owl in turn kills and eats both dug and snake and occupies the burrow as a nesting site. The numbers of the species in Manitoba will be somewhat restricted for a time because of the fact that very few of the burrows of our large grey spermophyle are large enough for a burrow for the owl and he has to hunt about until larger and quarters are available. But as I have stated in a previous pamphlet, he would he a welcome addition to our list of birds of prey because of his expert knowledge of gopher and spermophyle capture and his huge capacity for this class of food.

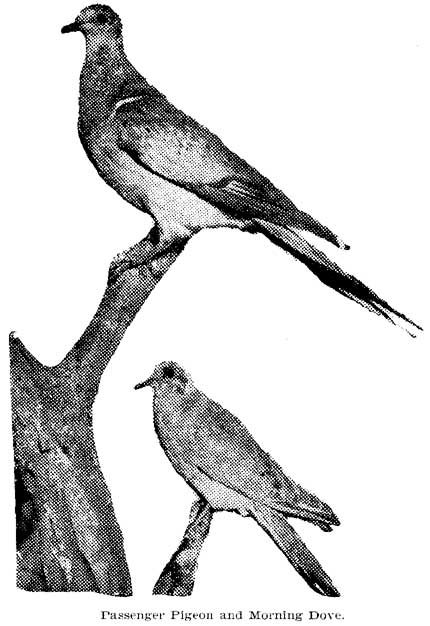

Reverting here from first and increasing records it will be quite in order to deal with disappearing species among rare bird notes. In the seventies and eighties when the effect of increasing settlement and clearance of feeding and breeding resorts of the wild pigeon first begun to make itself felt upon the species, the pioneers and press of the west noted an increased movement of the birds westward. This movement however, only lasted a few years and gradually the species, unable to find suitable environment, decreased in numbers until it first became uncommon then rare and seems now to have disappeared front among us altogether. When I first began scientific work in Portage la Prairie in 1897, I was promised dozens of pigeons, but every inducement offered failed to produce anything but mourning doves, and the only specimen I received or have heard of being taken in Manitoba since that time is one which was collected, at Winnipegosis, Man. on April 10, 1898, and sent to me to be mounted. It was a magnificent male bird in the pink of condition every way. No other specimen was noticed with it and no authentic records have been made since then, while Winnipeg taxidermists informed me that they had not received one for about five years previously. Many aspirants to the honor of recording a pigeon have arisen, but investigation has fallen. Even some of the old school who knew the birds so well in their youth and have in their eagerness mistaken mourning doves for pigeons. I have gone on many a tour to locate a pigeon seen by an old timer and have in my own inability delegated an assistant, but we have invariably returned with Zenaidura macroura, and the pigeon was not. The beautiful and well preserved specimen which I have been able to secure for illustration herewith is loaned me by Mr. Dan Smith of this city who shot it in St. Boniface, south-east of the cathedral in the fall of 1893 and, so far as I can discover, is the last authentic record in the vicinity of Winnipeg. Contrary to the opinions of many this bird has not been the victim of the gun but rather of changing conditions to which it was unable to adapt itself. Its kindred species, which it has been so often confused with, on the contrary being adapted to civilization and settlement is everywhere increasing with us.

There is little doubt in my mind but what within our provincial boundaries we would with systematic research be able to collect not only the greater redpoll but also Holboebls, Mealy and Greenland, but as these birds constitute with their intermediates and the two recorded species the common and hoary redpolls an intricate problem which very extensive collection and research alone will solve satisfactorily.

I am forced, however, to state that two specimens in my collection are undoubtedly of the large varieties rostrata and hornemanii. The specimen which I conclude is rostrata, or greater redpoll, is one which was collected in the winter of 1899-1900 at Portage la Prairie, among a very large flock of redpolls which were captured alive and kept in my aviary and while thus kept showed conclusively by its every action that it was a decided species. The specimen measures, length, 5 ¾; wing, 3 ¼; height, 3 ¼. This specimen died June 2, 1900, in aviary. The other which I believe to be hornemanii or the Greenland redpoll was picked up dead by myself near my aviary in the early spring of 1900, April : It is a female, length 6 ¼; wing. 3 ¼: tail, 2 ½. This is as far as I will venture on redpolls until my collection is examined at Washington and reported on.

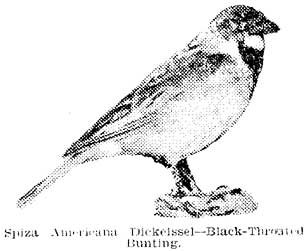

Probably one of the most unusual ornithological records for Manitoba is the dickeissel. On June 14, 1897, while doing, some miscellaneous collecting near the big slough at Portage la Prairie, a strange bird flushed out of the grass and alighted on a fencepost. I immediately secured it and was very surprised to discover that I had collected a fine male black-throated bunting. Needless to state I took considerable pains to preserve the specimen, and it is yet in my collection. I examined the locality very carefully but failed to find trace of any other specimens and concluded that this individual had very heedlessly wandered in company with kindred migrating species far beyond his own northern range, which is quoted as being occasionally as far north as southern Minnesota. I have watched carefully and constantly and made general enquiries but have been unable to record another specimen since that date. Their range extends over the width of the Mississippi valley line of migration as far south as Texas and should future conditions prove favorable we would welcome him as one of our regular summer residents.

Probably one of the most unusual ornithological records for Manitoba is the dickeissel. On June 14, 1897, while doing, some miscellaneous collecting near the big slough at Portage la Prairie, a strange bird flushed out of the grass and alighted on a fencepost. I immediately secured it and was very surprised to discover that I had collected a fine male black-throated bunting. Needless to state I took considerable pains to preserve the specimen, and it is yet in my collection. I examined the locality very carefully but failed to find trace of any other specimens and concluded that this individual had very heedlessly wandered in company with kindred migrating species far beyond his own northern range, which is quoted as being occasionally as far north as southern Minnesota. I have watched carefully and constantly and made general enquiries but have been unable to record another specimen since that date. Their range extends over the width of the Mississippi valley line of migration as far south as Texas and should future conditions prove favorable we would welcome him as one of our regular summer residents.

When I first began to study Manitoba bird-life I noted the absence of the well known barn swallow of the east from among the immense numbers of swallows found in the country, and for some years I did not see or hear a specimen, nor did I learn of any collections elsewhere in Manitoba. My first collection was made on the Portage slough on Aug. 5, 1901, of a fine male bird from a large flock of swallows careering about the slough, and I was much struck with the strangeness of the sight of a solitary barn swallow among so many of his related species. A few days subsequently I collected a second bird which was in very poor condition and noted one or two others during the migration. In the spring of 1902 a pair of birds reached Portage and took up their quarters under a small bridge over a slough some nine miles north of town and reared their brood, and last season (1903), I noted quite a large flock of the birds evidently several pairs breeding about the same locality under the bridge and inside one of the neighboring barns in the customary locality against a rafter. I was much pleased to note this wonderful increase in their numbers and have every hopes that with conditions favorable in the increasing settlement and building the birds will continue to increase and within a few seasons add one more species to the list of common birds in Manitoba. The long forked tail is always an identifying character while to learn the note once is to remember it forever, as distinct front every other swallow. A sharp metallic k-ching, k-ching.

On October 10, 1898 I received a fine male Mountain Bluebird from Mr. E. H. Patterson, of Brandon, Man., to be mounted. Knowing the species to be new to the Manitoba list I at once wrote Mr. Patterson asking particulars of its capture and was subsequently informed that it had been collected about two miles west of that city on Oct. 8, and was in company with another specimen of the same species. Whether this pair had been breeding in the vicinity or not I could not discover, but it is possible that instead of taking their courses south along the Rocky mountain migration route they had followed the Canadian transcontinental route to the eastward and this specimen at all events like the wise emigrant to Manitoba decided that attractions were sufficiently strong to induce it to remain. The range of this species is the mountainous region of the western States and Canada but as this and its kindred species our bluebird evince like several other species of birds a liking for a line of telegraph posts in travelling, it is quite possible that this pair have begun their winter migration along. The line of Canadian Pacific railway telegraph posts and continued eastward until the cold weather overtook them, and the cold lead collected this specimen in Manitoba. I have hoard of no further records of the species within our boundaries. This species differs from our common bluebird in having the entire plumage a rich blue, while the common form has the reddish brown breast.

Among rare records of a district there can fairly be included records of albinistic or partial albinistic ie. those plumages which are the result of the absence of the color pigment in the epidermis or outer skin producing a creamy white or piebald plumage. These plumages are not always permanent, but are liable to revert to the normal color after the first moult or change of hair. The color phase is regular throughout the entire sphere of natural life. It must not be understood that albinistic plumages include such as the weasel or ptarmigan or rabbit in winter color, as these are normal color changes for protection. The principal record I have of pure albinos is n specimen of the rusty taken at Dauphin on Sept 20th 1898. A creamy plumage of a duck which I take to be the ruddy duck, which it was taken at Arden, Man., on Sept. 8, 1900; this bird was alone on a pond and was shot for a gull. On June 14, 1897, I received a piebald or partially albino kingbird which had the white feathering scattered over the entire plumage, and the normally white flanks streaked with grayish. This specimen is now in the collection, of Mr. J.H. Allies, of Toronto. On Oct. 6, 1903, I received a robin in a similar plumage, taken at Yorkton, Assa. It has a plentiful sprinkling of the white feathers over the entire plumage, and presents much of a. harlequin appearance. These partial albino phases I fancy would revert to the normal plumage at the first moult.

Among rare records of a district there can fairly be included records of albinistic or partial albinistic ie. those plumages which are the result of the absence of the color pigment in the epidermis or outer skin producing a creamy white or piebald plumage. These plumages are not always permanent, but are liable to revert to the normal color after the first moult or change of hair. The color phase is regular throughout the entire sphere of natural life. It must not be understood that albinistic plumages include such as the weasel or ptarmigan or rabbit in winter color, as these are normal color changes for protection. The principal record I have of pure albinos is n specimen of the rusty taken at Dauphin on Sept 20th 1898. A creamy plumage of a duck which I take to be the ruddy duck, which it was taken at Arden, Man., on Sept. 8, 1900; this bird was alone on a pond and was shot for a gull. On June 14, 1897, I received a piebald or partially albino kingbird which had the white feathering scattered over the entire plumage, and the normally white flanks streaked with grayish. This specimen is now in the collection, of Mr. J.H. Allies, of Toronto. On Oct. 6, 1903, I received a robin in a similar plumage, taken at Yorkton, Assa. It has a plentiful sprinkling of the white feathers over the entire plumage, and presents much of a. harlequin appearance. These partial albino phases I fancy would revert to the normal plumage at the first moult.

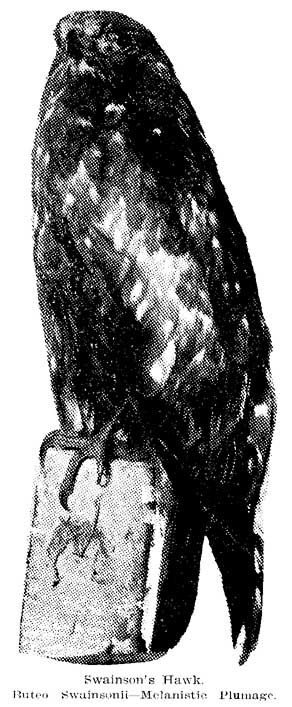

Converse to albinistic color phases we find melanistic phases among some forms due to a melanic or black deposit in the outer layers of the skin producing a black plumage or fur. Like albinism it may not be permanent, and specimen, may after first moult or change of hair revert to the normal color. This color phase is among birds most regularly noticed among the hawks. I have in several instances examined melanistic plumages of Swainson's hawk (Buteo swainsonii) and the rough-legged hawk (Archibuteo laqopus sanctijohannis), with the latter species it is quite a common color. With Swainson's hawk the darkest specimen I have handled in Manitoba was collected at Portage la Prairie, on Sept. 29, 1898, and was a young male bird.

On April 13, of 1899, another black specimen was brought in from the same locality, but closer examination showed it to be a female (Buto borealis) red tailed hawk, and much larger than Swainson's. While on May 30, of the same year, one of the boys of the town secured and brought me a very fine black male broad-winged hawk (Buteo latussimus). These two latter specimens were the first and only ones I ever saw of these species in melanistic plumage and the broadwinged hawk has been declared by many authorities to be a most remarkably rare plumage of that species.

It must be understood that melanistic coloration does not include the regular normal plumages of such birds as the blackbirds, crows, etc., but is simply an off color among some species with neither permanency or regularity.

I have also among the unusual records to note two hybrid records. On April 16 '97, I secured a beautiful specimen of the Flicker at Portage la Prairie, which proved to be a well-marked hybrid of the locally common yellow shafted and the red shafted Flicker of the south and west. This is not a new record, as C. auratus and C. chafer have interbred wherever their ranges overlapped, but it is a well marked representative of both types, and strange to state that it and another specimen taken near the same locality the same year are the only instances of this hybrid being taken in Manitoba for some years. The government museum at Ottawa contains a well-arranged series of this hybrid, with types ranging over the entire continent.

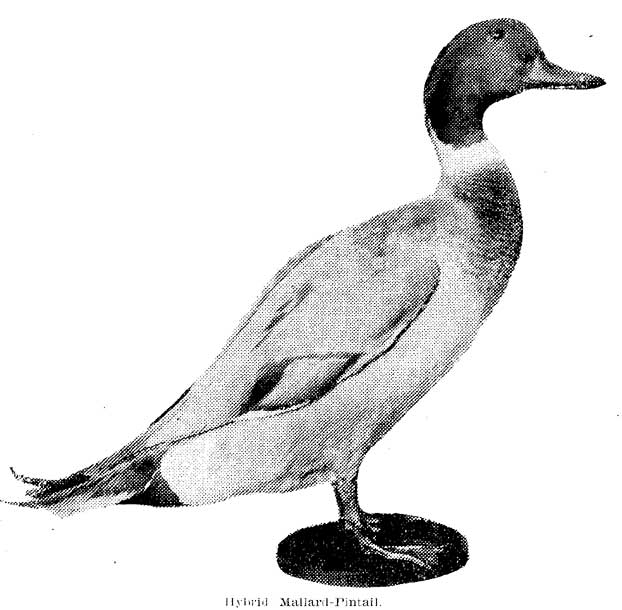

The specimen in my collection is in male plumage and has the cheek patches and wing and tail shafts bright red and a very small red patch on back of head. While Hybrid Flickers have been recorded previously, I have but one record from any quarter beside the one before us of a hybrid Mallard Pintail. In the early part of October 1902, a young man secured this specimen which is as typical of both species as could possibly be at the Clandeboye marsh and brought it to a local taxidermist to be preserved. I subsequently heard of the bird and sent the owner for it, managing finally to redeem it from the hands of the mechanical birdstuffer in time to preserve some semblance of its originality. It combines remarkably well the characteristic shape and markings of each species, having the head and bill of the pintail somewhat larger, with a mixture of the mallard green and pintail bronze, the chocolate breast of the mallard, pintail back and wing coverts; mallard wing markings, pintail tail, with the long feather partly curled, the mallard tail coverts upper and lower and the red feet of the mallard. The mallard ring on the neck runs into the white stripes of the back of the pintail neck and does not completely encircle it. The only other record I have ever heard of this hybrid was made in 1889, when Mr. Cross, of Toronto, received a specimen shot at Scugog Lake, Ont., and which was mounted, exhibited and described at a meeting of the biological section of the Canadian institute.

Page revised: 22 May 2010