by Cornelius S. Prodan

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Manitoba Pageant, Winter 1979, Volume 24, Number 2

|

The following two articles are from C. S. Prodan’s unpublished manuscript, “The Story of the Water District.”

The building of the Greater Winnipeg Water District Railway and Aqueduct was instrumental in bringing settlers to the area south and east of Medika, an area later to be called the Water District. It therefore is appropriate to relate here the steps that led up to the building of the railway and aqueduct and to give the reader a brief glimpse of the building itself.

Winnipeg was a sprawling but thriving community at the turn of the century. As its population grew, so did its industry. An adequate supply of suitable water began to be a limiting factor. The water supply came from seven wells located along McPhillips Street and the water was very rich in minerals. This made it unsuitable for industrial use as it clogged boilers and made laundry operations very difficult. The heavy use of water by the increasing population also reduced pressure to the danger point in fire fighting. In 1906 a Water Supply Commission of the City of Winnipeg was established by a special Act of the Manitoba Legislature. This commission appointed a Board of Consulting Engineers. These engineers, after due investigation, recommended to the Water Supply Commission that the City of Winnipeg go to the Winnipeg River for its future water supply. The Commission, in turn, recommended to the City Council that the recommendation of the Board of Consulting Engineers be implemented. The City Council did not do this due to financial conditions.

In 1912, upon a request of the City of Winnipeg, the Public Utilities Commission made a study of the water supply for Winnipeg. Its recommendation was that Shoal Lake, part of the Lake of the Woods, would be a logical water source and that other municipalities might join in this project.

On 7 April 1913 the Winnipeg City Council appointed the Board of Consulting Engineers to investigate and submit a report on the best means of getting the water supply from Shoal Lake, together with an estimate of costs. On 20 August 1913 the report of the Board of Consulting Engineers was received. It showed that Shoal Lake could supply 85,000,000 imperial gallons of water daily, an ample amount to satisfy the needs of an 850,000 population. The estimated cost to construct an aqueduct 96.5 miles in length was $13,045,000.00. The water would flow by gravity as Shoal Lake was nearly 300 feet higher than Winnipeg. The Greater Winnipeg Water District was incorporated by a special Act of the Provincial Legislature of Manitoba, assented to on 15 February 1913. On 1 May 1913 a vote was taken on this project which showed 2,226 in favor and 369 against.

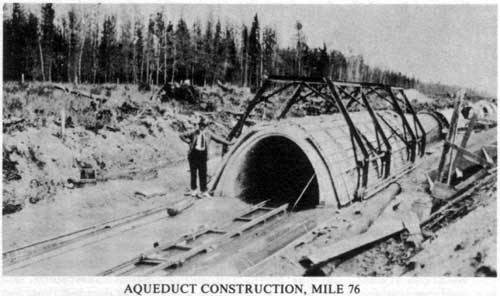

In order to facilitate the construction of the aqueduct as well as to provide patrol facilities in future years, the Greater Winnipeg Water District Railway was built first. In the fall of 1913 the surveying of the right of way was done and construction commenced in 1914. By the end of 1915 this railway was near completion. Most of the land for the right of way for the project was received as a grant from the Dominion Government as an encouragement for colonization of the area. Besides the grant for the right of way, the Commission had an area for establishing settlements, allotting parcels of land of 40 acres to a settler. There were many difficulties in building this railroad because it traversed pre-cambrian rock, gravel, stone ridges and rivers, as well as numerous muskegs and swamps. According to the recollections of Mr. D. L. McLean, retired employee of the Greater Winnipeg Water District, the construction of this railway proceeded with energy, determination and courage. In the vicinity of Mile 84-90 the railway had to cross some six to eight miles of muskeg and it was necessary to construct corduroy logs like floats. These floats were filled with gravel, muck and sand in order to sink them until a road bed firm enough to withstand engines and freight cars with gravel could be obtained. Mr. S. H. Reynolds, Assistant Engineer and later a chairman of the Commission, worked almost day and night to finish this job as soon as possible. As many as 1,000 men worked at one time on the construction of these utilities.

During the construction, stop-over points were named by station numbers. Later on stations were designated as Mile so-and-so. In time with the establishment of settlements, names were given to stations. Thus, the first station from Winnipeg was named Deacon in honor of Mayor T. R. Deacon. Mr. Deacon was mayor of Winnipeg from 1913-14 and it was during his term that the construction of the railroad commenced. The Millbrook station was named after the settlement of Millbrook. Monominto and St. Genevive as well as Larkhall were named by local people.

Spruce was named after a very dense growth of spruce timbers. Station Reynolds at Mile 64 was named in honor of the engineer and commissioner S. H. Reynolds who spent many months at the “White House” on the west banks of the Whitemouth River. McKinley siding at Mile 69 was named in honor of Mr. W. McKinley. He was the superintendent in charge of wood and fuel cutting. This fuel supplied the City of Winnipeg wood yards located at the terminal of the Greater Winnipeg Water District Railway in St. Boniface. McMunn station was named after James A. McMunn, the settler, first postmaster of McMunn post office and the first justice of the peace in the district. East Braintree was named by Mr. Victor Watson who came from Braintree, Massachusetts. In order to avoid mistaken mail deliveries, the postal authorities in Ottawa requested the addition of the word “East” and so this post office became known as “East Braintree.” Glenn was named for its location at a low open space among the heavy tree growth - a shady nook in the woods. Station Haute, meaning height in French, was named by woodsmen. The last station, Waugh, Indian Bay post office, was named in honor of Mayor R. D. Waugh, of Winnipeg, during whose term of office from 1915-16 the construction of the aqueduct was begun. In 1918 Mr. Waugh became the chairman of the Board of Commissioners.

The construction of the aqueduct began in the spring of 1915. On 20 March 1919 the water from this aqueduct was turned on at the McPhillips terminal.

The construction and operation of the Greater Winnipeg Water District Railway and the aqueduct played a very important part in the opening and development of this area. A large number of men found employment during the construction. After seeing the country and the quality of the land, many decided to stay in the district. Others came here because homesteads were available. Many came because of the wealth of forest that was waiting to be harvested. A number found permanent or seasonal employment patrolling or servicing these utilities. Nearly all the employees of the Greater Winnipeg Water District working in these areas have their farms and homes there. The railroad runs through a heavily wooded area. Thousands of cords of fuel wood were shipped on this railway. Jim Ray, conductor of this railroad in the thirties, stated that this road was the only one in Canada that showed a profit in its annual operation. Thousands of cords of pulp wood and fire wood were freighted but gravel, sand, household requirements and farm products of the area were shipped on this road. Passenger service was also available but only as a concession of convenience to the settlers and the woodsmen. It operates as a privately owned railway and is not subject to the regulations of the Railway Commission of Canada.

Aqueduct construction, Mile 76.

During the years 1916-18 the Board of Commissioners publicized this district extensively. A pamphlet of that time stated - “Many settlers are being attracted to this locality, partly because of the prominence given to the scheme and partly because the drainage done by the District in reclaiming large areas of land. The land along the rivers is exceptionally rich and is being settled rapidly. In most cases the value of the wood cut, more than pays for the clearing of the land.” This was an exaggeration to some extent. “Experimental gardens along the line of the railway have yielded exceptionally well and the Department of Agriculture for the Province of Manitoba has established, at Reynolds, an experimental station with a view to helping the settlers already located and to demonstrate the possibilities of the district. Free homesteads of approximately forty acres can be obtained along the Birch River and close to the railroad.”

As far as the experimental station at Reynolds is concerned, the writer was unable to establish where and when it existed. At about the same time the Manitoba Government established a prison farm known as the Provincial Gaol Farm, located two miles west of East Braintree. Very likely this was the institution about which the promoters of the scheme were talking. Shortly after the Provincial Gaol Farm was established the late Governor Downie initiated a project for producing quantities of vegetables and feed for livestock on this farm. This project was difficult because the heavily wooded land had to be cleared. This was done by the prisoners. The growing of crops was handicapped by a lack of appropriations to buy the necessary implements. Some of the implements had to be borrowed.

The original cost of building the railroad and the aqueduct was around $13,050,000. By 1960 the equalized assessment of these utilities was valued at $136,646,000.00.

The aqueduct supplies water of 85,000,000 gallons per day to a community in excess of one half million persons. The conception, foresight and courageous completion of this project of such magnitude endows great credit to the leaders and the citizens of Winnipeg of the day. The project was and continues to be an unqualified success.

Winnipeg can be justly proud of the quality of its water. During the Royal Tour through Canada, the Winnipeg Free Press had the following article in its issue of 30 June 1939:

Shoal Lake Water, Specially Bottled, Used on Royal Tour

Long before the Royal visit, samples of drinking water from more than one hundred places throughout Canada were sent to the Dominion Health Department at Ottawa and carefully analyzed for microbes. It was found that the purest drinking water of any western samples was from Shoal Lake, Manitoba. So it was decided that their Majesties should drink only Shoal Lake water all the time they were in the West, to protect their health. Constant changes of drinking water on the long journey might have subjected them to the risk of infection.

See also:

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Winnipeg Aqueduct Monument (James Avenue, Winnipeg)

Page revised: 3 April 2011