by W. Leland Clark

Brandon, Manitoba

Manitoba Pageant, Winter 1978, Volume 23, Number 2

|

Newspapers throughout Canada carried frequent accounts of Indian and Metis unrest during the early months of 1885. However, it was the story of the Metis victory at Duck Lake on March 26, 1885 that electrified the nation. The North West Mounted Police had been defeated and the Canadian government responded immediately by dispatching a sizable militia force westward by the all-but-completed C.P.R. [1] While the Canadian force was divided into three main columns, most of the public interest was focused on the activities of Major-General Middleton and his 800 member contingent as it was their objective to attack Batoche, the headquarters of Riel's provisional government. The rebellion and the Canadian government's effort to suppress it was obviously "news" of the greatest possible significance and many newspapers responded by sending special "field correspondents" to the North West Territories. While their reports of the several military engagements were eagerly awaited by the newspaper reading Canadian public, the reminiscence of George A. Flinn one of those reporters - is of historical interest in itself. [2]

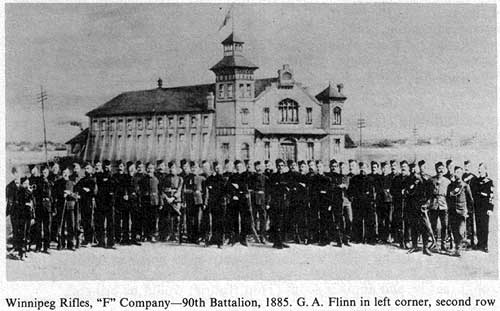

Flinn, who had come to Winnipeg in 1882 from St. Paul, Minnesota, was a reporter for the Winnipeg Sun [3] when hostilities commenced in early 1885 and Thomas H. Preston, the "Managing editor and part owner," [4] directed that Flinn should accompany the first contingent of the 90th Battalion of Winnipeg Rifles (who had been mobilized on the evening of March 25) as they - about 100 strong journeyed westward by a special train over a recently completed section of the C.P.R.

Unfortunately for all concerned, the winter of 1885 was unduly long and rather severe weather conditions prevailed at the time of their arrival at Qu'Appelle late in March. There was still eighteen inches of snow, Flinn estimated, on the ground and he was forced to find shelter with the men in an emigrant shed - the only hotel having been occupied by the officers.

By April 2nd, the force (including the bulk of the 90th battalion - about 260 men - who had subsequently arrived) had been relocated at Fort Qu'Appelle where the preparations for the march northward commenced. However, these newly mustered militia units were, in Flinn's opinion, very badly equipped for the task that lay ahead. Most of the men were armed with "antiquated Snider rifles" whose "cartridge was a fat, stubby affair with a soft lead bullet plugged with clay and when the bullett [sic] hit any hard object it mushroomed like a small umbrella." [5] The teamsters, it was reported, were even less well equipped with their "Peabody" rifles, "the ammunition for this antiquated arm being so ancient that when a cartridge did `go off it was a shocking surprise to the man with the rifle." [6] While a handful of qualified marksmen were issued with the much superior Martini-Henry rifles, and although the contingent's fire power was subsequently augmented by the new and awesome Gatling gun, Flinn concluded that "seldom has a military force been sent out so poorly equipped for war, but fortunately the soldiers, with a few exceptions, were inexperienced and any gun was a good enough gun to them ..." [7]

After a few short days spent in preparation, General Middleton began on April 6th the task of marching his citizen army from Fort Qu'Appelle to Batoche, a distance a little in excess of two hundred miles. With temperatures reaching a low of 23° below zero and winter conditions prevailing, the column of some four to eight hundred men [8] averaged about twenty miles per day. Camping at night on the open prairie was somewhat of an ordeal and Flinn noted that the soldiers, in an effort to compensate for the scarcity of blankets, slept "spoon fashion, resting on one side until their lower sections on the frozen ground got too numb and then, on signal, rolling over with due regard to the distribution of the scanty blankets." [9]

The monotony of the march was broken very infrequently as this small army moved slowly forward. For example, the most exciting event that had occurred by the time the column reached Humboldt was the "capture, by purchase of course," [10] of a sack of oat meal and a can of molasses from which a breakfast of hot "porridch" was eagerly made - an incident of some importance to the men of F Company of the 90th Battalion, most of whom were of Scottish origin! On other occasions, "a wild-eyed fugitive settler would drift into camp and tell the most weird and blood-curdling stories of activities and massacres, for the most part pure invention, but it was difficult at times to separate truth from fiction." [11]

By April 17th, Middleton's force had reached Clarke's Crossing on the South Saskatchewan river. [12] A week later on April 24th (and almost a month since their mobilization), the inexperienced troops underwent their "baptism of fire" when they were ambushed by Metis forces at Fish Creek.

Although Flinn was a non-combatant, he was, during the course of this engagement which was of several hours duration, provided with "an old Snider rifle." However, the Winnipeg newspaper correspondent showed remarkably little desire for an active military role: "as I had no personal grudge against the halfbreeds, I tried to shoot a lung out of that threshing machine." [13] An hour later, "about noon, having fired off my ammunition at the rebel threshing machine ..." [14] Flinn withdrew to the rear to assist as a stretcher-bearer, a task for which he had more enthusiasm. Unfortunately, one of his assistants in that task was a rather unwilling teamster whose frequent dives for protective cover, whenever they were under fire, meant that the task of conveying wounded men was difficult at best, to say nothing of the discomfort suffered by the injured who were being transported!

Flinn's major responsibility, of course, was to serve the interests of his newspaper and that, on occasion, was difficult to do. For example, the Fish Creek battle occurred only eighteen miles from an all important telegraph office at Clarke's Crossing but the many reporters often encountered difficulties in reaching such telegraph offices. By early afternoon, on the day of the Fish Creek Battle, Flinn had compiled a complete list of casualties and an account of the day's fighting for transmission to the Winnipeg Sun. He was, at that point, persuaded by the other correspondents "that it was too big a thing to be dealt with in a competitive way for everyone in Canada was deeply concerned over the safety or otherwise of the citizen soldiers." Flinn somewhat reluctantly agreed to a joint dispatch being filed by all of the correspondents with his compiled list of casualties forming an important segment of that report. Flinn, however, discovered later that same day that both his name and that of his newspaper had been omitted from this joint dispatch, and rather naturally he refused thereafter to be a party to any such cooperative reporting ventures.

The battle of Fish Creek was also significant in that relations between General Middleton and the press corps deteriorated considerably after that event. For example, one reporter who had erroneously reported the defeat and retreat of Middleton's force at Fish Creek was "called on the car-pet, given his walking papers, and sent out of camp." [16] Subsequently, General Middleton, during the initial stages of the fighting at Batoche, informed Flinn that no news reports should be dispatched until hostilities had ceased. The estrangement between the commanding officer and the press corps may well have contributed to the subsequent uncomplementary "picture" of Middleton that was to emerge after the rebellion.

After the encounter at Fish Creek, the column remained encamped until May 8th, when Middleton moved into position about nine miles from Batoche. The seemingly hesitant, indecisive probing that characterized much of the four day long battle of Batoche then began. While many Canadians would be critical of the British general's seemingly excessive hesitancy during those last days, Flinn was somewhat sympathetic.

If General Middleton had been in command of a force of soldiers of the regular army, he would, no doubt, have rushed the attack and ended the fight the first day, but he was, if any thing, over-anxious to conserve the lives of his citizen soldiers and the fight was consequently prolonged to the fourth day when these citizen soldiers showed that if they had been allowed, they would have cleaned up the rebel force at Batoche, in short order, the first day. [17]

However, even on the May 12th - the fourth and final day, the attack did not unfold as planned. A "feint attack" was to be launched by the mounted units and supported by the Gatling gun on the extreme right of the Metis' line of defence while Lt. Col. Straubenzie was to lead the main attack on the village. "Just what happened possibly the orders were misunderstood - is not very clear, but the troops under Straubenzie failed to make the advance and Gen. Middleton came back in a towering rage and sat down to dinner." [18] Ironically, while Middleton was in the midst of his "lunch," the final attack was successfully launched!

Meanwhile, thanks - it would appear - to the efforts of George Flinn, Canadians in many parts of Canada were kept well informed of developments - such as they were! On each of the four days of the battle of Batoche, Flinn's material was the first to hit the streets in Winnipeg, Toronto and Montreal. The Winnipeg Sun ran an extra edition of some 30,000 on the first day of the battle and the Toronto Telegram, for whom Flinn was also reporting, sold 29,800 copies of their "extra" on that same date. Flinn, in his account of the campaign, gave particular credit to two independent guides and scouts, Bill Armstrong and Bill Diehl, who helped carry despatches during the fighting. Unfortunately, General Middleton's official reports to his own Minister were delayed on Mav 12th for several hours when the telegraph service was disrupted just after Flinn's report had been sent. Thus, the Canadian government found itself reading the reports of this "field correspondent" and hearing of the victory in the North West in the same manner as did the rest of the newspaper reading public!

Although the battle of Batoche ended suddenly and decisively on May 12th, the work of the newspaper correspondents continued unabated. One of the first issues with which Flinn, and other correspondents, investigated was the charge, apparently originating with Father Andre and published in the Toronto Globe, that Canadian soldiers had discredited themselves by wide-spread looting after the cession of hostilities. Flinn, and other correspondents whom he cited, categorically denied that such extreme looting had occurred: "The only loot I saw was in possession of the families of halfbreeds and Indians, and it had unmistakably been stolen from the stores of the white merchants at Batoche and Duck Lake, the shop labels being on some of the goods." [19]

Despite Middleton's victory at Batoche, the rebel leaders were still at large. Gabriel Dumont, it was soon learned, had fled to the United States but Riel remained in the vicinity. When Flinn reached Middleton's new camp at Gardepui's Crossing which was about twenty miles north of Batoche, he - according to his own account - was informed by one of the scouts (Armstrong) that he and another scout (Tom Hourie) would be bringing Riel in and that if I happened to be somewhere along the river trail in a few hours, I might see something of them.

Evidently Riel's arrival was expected, for the soldiers were all ordered to remain in their tents and Boulton's Scouts who had individually and collectively sworn to hang Riel on sight were sent out on a wild-goose chase to hunt for Riel where he was not. So everything was safe and comfortable for Riel when he came plodding along the river bank below the trail, escorted by Armstrong and Hourie. I met them some little distance from the camp and certainly Riel looked very much unlike a leader and prophet. He was roughly dressed, - no coat but a capacious vest; his beard and hair needed the services of a barber and he was as nervous as a cat in distress.

'Will I get a civil trial?' he asked Armstrong.

'No, you will be court-martialled' replied the scout, who apparently was not favorably impressed with his prisoner.

Riel thereupon prayed a little and then he put his hand in a vest pocket and produced a small 22-caliber revolver which he held out to Armstrong with the remark: 'See what I might have done to you. I am acting in good faith though.'

Armstrong took the little weapon, held it on his open hand and extracted five small cartridges from it, one of which he handed to me for a souvenir. [20]

While Riel was being escorted to Middleton's camp, Flinn commenced the now seventy mile journey to Clarke's Crossing and a telegraph operator. In order to cross the Saskatchewan river at Clarke's Crossing, Flinn had to secure the assistance of the men on the Baroness, one of the area's riverboats. Even this proved to be difficult: "I fired three shots from my revolver, shooting down stream so that the sentry could see by the flashes he was not being fired at. He promptly raised his rifle and blazed away at us, but nothing happened except the whee-ee of a bullet." [21] Fortunately for Flinn, the officer in charge came to his rescue, a boat was provided and the first news of Riel's capture was soon sent east. George Flinn and the Winnipeg Sun had scored another "scoop."

From Gardener's Crossing, Middleton's forces marched to Prince Albert but Flinn preceded them in an effort to investigate the rather controversial role in the rebellion of the 175 well armed mounted police who were garrisoned there. As a result of numerous interviews, Flinn concluded in a letter published in the Winnipeg Sun on June 2, 1885 that there were many reasons to criticize the role of the N.W.M.P. who by then were locally referred to as "the gophers." Under the leadership of Colonel Irvine (whose conduct Flinn described as being "utterly incomprehensible" [22]), the N.W.M.P. had ventured out of Prince Albert on only one inglorious occasion - a manoeuvre that was marred by their very hasty withdrawal to the safety of the town immediately upon hearing rumours of some Indian activity in the area. Flinn was also very critical of their decision to arrest and to detain several local residents without charges being laid. Charles Nolin, due to his opposition to the Metis leader's policies, had been imprisoned by Riel prior to the outbreak of hostilities. When Nolin later fled to Prince Albert, he was immediately arrested and imprisoned from March 27 to May 23 without being charged - despite the fact that the police had invited everyone who had been forced to participate in the rebellion or who had been detained by the Metis against their will to come to Prince Albert for "police protection." Flinn concluded that the report of Charles Nolin's incarceration "effectually debarred any others who might have been so inclined, from taking advantage of the proclamation." [23] Thomas Scott, an English half-breed, was one of several white settlers in the Prince Albert district who had supported the constitutional attempts to secure a redress of grievances. Scott, too, had been arrested when he came to Prince Albert (to sell some pork) and he, also, was held without charge from April 3 to May 23 when "he was allowed to depart without ever knowing why he had been imprisoned." [24] As a result, Flinn concluded that the Habeas Corpus Act must be enforced in the west and that the North West Mounted Police should be disbanded and replaced by "garrisons of soldiers who would command the respect of the Indians ..." [25]

While in Prince Albert Flinn also interviewed Father Andre, the head of the Benedictine mission at St. Laurent, and the man whom Riel had visited soon after his return in July 1884 from Montana. According to that interview,

On Riel presenting himself Father Andre [had] expressed his regret at seeing him and hoped he had not come with any evil purpose. Riel assured him his intentions were good, and whatever he did would tend towards the welfare of the church and the poor halfbreeds. Father Andre expressed his doubts that such was the case, but Riel, thinking to secure his aid by one grand coup said that whatever was obtained by the half-breeds, whether by constitutional means or force of arms, the church should have its share, and not only the tenth of everything as ordained by scripture but a seventh ... if Father Andre and the rest of Catholic clergy would lend him the might of their influence. The reverend father, however, remained firm and told Riel he had let the cat out of the bag, and he now saw he came with bad intentions and would be the cause of bloodshed. Riel thereupon flew into a violent rage, and shaking his fist swore he would triumph in spite of the church, and he would trample the priest under his feet. He raved and stormed for quite a time, but finally calmed down and began to perceive he had made a mistake. [26]

The priest reportedly did not see Riel again until the end of November 1884 when Father Andre advised the Metis leader to leave the country. Riel allegedly replied that he was penniless and in debt:

He said if the government would give him $2,000 he would go down into Lower Canada, or anywhere the government told him, and remain quiet. He said he could tell the halfbreeds he was going down to further their interests at Ottawa and they would believe him ... He then commenced to complain bitterly of the manner in which the Government treated him in 1870, Sir John Macdonald having promised him $30,000, which he did not receive, to leave the country.... He now considered the Government owed him the money he had not received and the least they could do for him was to give him enough to carry himself and family to Lower Canada where he would be amongst friends and always under the eye of the Government. In case the Government refused to accede to his demand he would raise such a storm that it would cost them thirty millions of dollars and much blood before they should subdue it. [27]

Father Andre, according to Flinn's report, subsequently agreed to intervene on his behalf in order to secure the necessary $2,000 from the Canadian government. Through the agency of one D. H. McDowell of Prince Albert, a request was made, in late December, to Governor Dewdney of the North West Territories, whereupon the proposal was reportedly forwarded to the Prime Minister. Riel, in the meantime, had agreed to delay any further decisions for forty days.

During the course of the forty day "interlude," Riel apparently consulted Father Andre on various occasions, only to be disappointed by the lack of communication from Ottawa. After the expiration of the forty day period, another letter was sent to Governor Dewdney "and a reply came to the effect that he (the Governor) did not wish to hear anything more about Riel, as it annoyed him." [28]

The enraged Riel, according to this account, began immediately to prepare for rebellion. Even so, it was Flinn's opinion that it was the provocative and foolish remarks of the Hon. Lawrence Clarke (the factor for the H.B.C. in Prince Albert and a man for whom Flinn had little sympathy) who allegedly told the Metis that the response to their petitions was coming in the form of 500 police and the government's answer would be "in the shape of bullets" [29] that led to the ultimate decision to rebel. As a result, the "half-terrified, wholly-infuriated half-breeds exasperated beyond endurance, flew to arms ..." [30]

Although Flinn did accompany Middleton's troops to Battleford and although he subsequently attempted in vain to interview Big Bear, the Winnipeg reporter's single remaining consequential connection with the 1885 rebellion was a brief visit with Louis Riel on the eve of the latter's execution. However, Flinn - at that moment in the employ of the Daily Manitoban, a successor to the Sun - spent only a few moments with the doomed man during which time he agreed to convey a "letter of thanks" from Riel to J. W. Taylor, the American consul in Winnipeg, and to ensure that the contents of the letter would be published.

However Flinn's principal responsibility - as a newspaper reporter - was to convey the report of Riel's death as quickly as possible to the "outside world." According to his own account, Flinn - who had seemingly won more than his share of "scoops" during the actual rebellion - arranged, in conjunction with two other reporters, that the telegraph lines would be held open for them - to the exclusion of other reporters. It was Flinn's responsibility "to signal to Diehl and Ewer the moment the drop fell." [32] This Flinn did and thus their message was the first to be sent "to the grief of other correspondents on the ground." [33]

While George A. Flinn's impartiality and judgement as an historian could obviously be questioned, [34] the recollections of his experiences as a correspondent (who was, in essence, sympathetic to Middleton and his army - but not to the Canadian government) provide an interesting insight both into the history of the 1885 campaign as well as into the role of a pioneer "war correspondent." While the "George Flinns" have been excluded from the histories of that era, their "on the spot" reports were significant - as a foundation for the initial public reaction and as a source for historians. While the "George Flinns" of yesteryear cannot be described as the "makers of Canadian history," they do deserve credit for their role in the initial stages of the "recording of history."

1. In fact, the decision to send a military expedition to the North West Territories had been reached before the defeat at Duck Lake. George F. G. Stanley, Louis Riel (Toronto, 1963), 324.

2. Flinn's diary of his experiences during the 1885 campaign is of limited significance as a historical source. However, his somewhat rambling, written recollections, which were prepared for the Winnipeg Free Press on the fiftieth anniversary of the rebellion, is a more voluminous and interesting document. A lengthy extract of these recollections was published in the Free Press on June 1, 1935.

3. The Winnipeg Sun, which was owned by W. H. Nagle, was succeeded in mid-1885 by the Daily Manitoban - a paper which, in turn, was absorbed by the Manitoba Free Press.

4. Public Archives of Manitoba (P.A.M.), George A. Flinn Papers.

8. Middleton began the march with 402 men and a wagon train of 120 vehicles. Augmented by reinforcements, his force numbered 800 by the time he reached Clarke's Crossing. Stanley, Louis Riel, 325.

9. P.A.M., George A. Flinn Papers.

12. While the ice had "gone out" by that date, the spring waters were ill-suited for the correspondent's much-needed laundry purposes: "I cannot say that the color of the garments was improved by the muddy water." Ibid.

24. Ibid. Thomas Scott, however, was subsequently charged with treason - felony. He was found not guilty. Sandra Estlin Bingaman, "The Trials of the 'White Rebels', 1885," Saskatchewan History, Spring, 1972, 41-54.

25. P.A.M., George A. Flinn Papers.

31. The contents of the letter were of no particular consequence.

32. P.A.M., George A. Flinn Papers. Diehl and Ewer, who were reporters for the Manitoba Free Press, were Flinn's partners in this instance.

34. Flinn, for example, wrote of Riel's attempt in 1869-70 to "establish a Metis Republic and to create an independent state" and he, in addition, described Big Bear - who had refused to be interviewed - as "that blood thirsty Indian who with his tribe of murderous savages, descended upon the settlement at Frog Lake and perpetrated a horrid massacre ..." Ibid.

Page revised: 20 July 2009