by John Charles Reifschneider

Manitoba Pageant, Summer 1976, Volume 21, Number 4

|

In February 1909 when I was nineteen years old I arrived in the hamlet of Beausejour with a Green Glass Bottle Blower journeyman’s card in my pocket. I had learned my craft in my home town, Belleville, Illinois. Subsequently I worked in Alton, Illinois and Wallaceburg, Ontario before moving to Beausejour to find employment with the Manitoba Glass Works. The factory at Beausejour closed annually during July and August. I returned to work there for three consecutive years.

John Charles Reifschneider (1973) by Nita Spangler

Source: Archives of Manitoba, John Reifschneider Collection 4, N17061

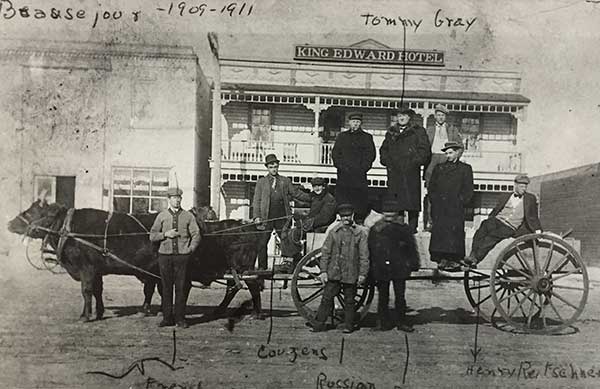

Beausejour had three hotels in 1909. The King Edward Hotel was built by Willie Lance, who was unable to procure a licence to operate it after completing the hotel. He sold it to William Bethel who did not get the licence and later sold it to his brother Robert. Howland’s Boarding House, which had a large sign in front on the roof “Temperance House,” was operated by Harry Howland and his wife Anne. Harry also had a blacksmith shop and Anne was one of the early teachers of the Beausejour area. The Beausejour Hotel was owned by Mr. and Mrs. J. N. Lacasse, but the operators were Mr. and Mrs. Morris Diner. The latter hotel had a bar and the only pool table in town. The bartender was Jack McNab.

Glassblowers on an ox-drawn wagon in front of the King Edward Hotel at Beausejour (1909-1911)

Source: Archives of Manitoba, John Reifschneider Collection 10, N17066

The main street in Beausejour was wide, muddy in winter, dusty in summer and generously paved with oxen and horse manure.

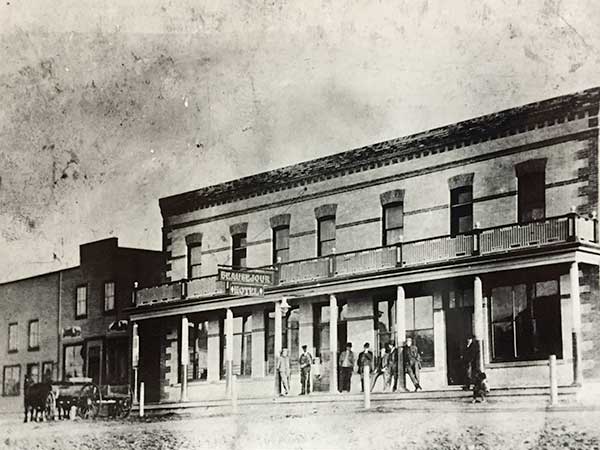

I stayed at the Beausejour Hotel which charged $5.00 per week for room and board. This included transportation to and from work at the glass factory in a two seated vehicle called a “democrat” drawn by a team of horses. The two seated vehicle also served the hotel operator and his wife; each occupied a seat. The distance from the hotel to the factory was slightly less than a mile and the ride usually became a race between vehicles of the hotels transporting the glass workers. A remarkable fact is that no serious accidents occurred during those reckless, high-speed trips, racing each other to reach the factory.

Beausejour Hotel (1909-1911)

Source: Archives of Manitoba, John Reifschneider Collection 8, N17064

The glass workers came from Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and California. Rarely did they stay at one place for any length of time. Those who worked briefly at any one place were called “doghairs.”

A few glass blowers stayed in Beausejour long enough to be joined by their wives, but they did not stay long. Living conditions were difficult, temperatures extremely cold. Hotels were poorly heated, the frost on the windows at times formed an inch thick.

One time, I recall the heat was very poor in the Beausejour Hotel. I went down to the basement to find nearly all the heat ducts closed and the numbers to the rooms removed. My roommate stayed in the room and dropped a marble down the duct to help me locate the one to our room. We turned the damper and got heat.

The Beausejour Hotel had one bathroom on the second floor. It was always busy; guests had to wait in line, and there never was enough hot water.

There was an out house at the rear of the hotel which had two holes, tilted seats and a barrel under each hole. It had a stove and wood, but there never was a fire in the stove. Each visitor furnished his own paper. The building contained much poetry on the walls; original or otherwise, contributors signed their autographs.

Jack McNab, bartender of the Beausejour Hotel was usually called upon to settle arguments and fights in the bar and on the premises of the hotel. When a fight started, Chief of Police, Mike Hoben, ordered the combatants outside to settle their grievances, after which they returned to the bar and had drinks on the house.

Law officers of that time were Chief of Police, Michael (Mike) Hoben, Police Officer, Thomas (Tom) Deaken, and Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Robert (Bob) Davie. There was a small jail on the left side of the Main Street at the east edge of town. Nearby was a Chinese laundry whose owner was the landlord of the “establishment where the girls stayed” when they came from Winnipeg. Just east of the Beausejour Hotel was the barber shop, operated by “Curley” George McAughey.

Recreation and entertainment for glass blowers was more spontaneous than planned or organized. Hunting game on the outskirts of town, in the surrounding country or fishing in the Brokenhead River was convenient. Snowshoe rabbit, moose, prairie chicken and bear were available. Many times, howling wolves reminded us of the wilderness only a few short blocks away. My brother, who also was a glassblower in the factory at this time, told a story of a bear chained in front of the King Edward Hotel which was teased and tormented for amusement. On one occasion the bear bit a glass blower in the calf of the leg. The animal was destroyed.

Interior of Manitoba Glass Factory, Beausejour, c1910

Source: Archives of Manitoba, John Reifschneider Collection 36, N17086.

Two citizens, Alex Waddell, Canadian Pacific Railroad agent, and William Maddin, merchant, made a record kill of moose near the present site of the Pinawa Radar Station, eighteen miles east of Beausejour. One moose had a seventy-two inch and the other a seventy-four inch spread of antlers.

When the warm days of late spring and summer approached there was a change of pace. A walk to the Brokenhead River two miles east of town was a good place for glass blowers to “get their feet wet” after too much drinking.

Baseball was a popular sport for everyone, activity for the players, amusement for the spectators. Some glass blowers were good players. Perhaps the residents overlooked the “horse-play and high jinks” that went along with glass blower drinking. A good baseball team was important when the team played in neighboring towns.

Card games and drinking on the porch of the Beausejour Hotel on Sundays was tolerated but definitely not approved by either the Chief of Police or the local residents who passed the hotel on their way to church.

Liquor was cheap. A large glass of whisky sold for ten cents, and a full quart of Johnny Walker or other brands was ninety cents.

Occasionally and at holiday times, glass blowers went to Winnipeg via Selkirk on the Canadian Pacific Railroad. It took about three hours to travel the thirty-nine miles. The train was a combination of two passenger coaches and several freight cars. On the return trip the train stopped and switched cars at each station. The conductor said, “We run fast and stop long.”

On these trips the glass blowers sold the whimsies they made on their own time. They included glass canes, chains, lilies, and paperweights which were eagerly sought by patrons and bartenders in Winnipeg. Later the superintendent of the glass factory stopped the activity of making whimsies on Sundays as a pastime.

During the last visit to Beausejour in September 1973, I met Louis (Whitey) Vogel, a retired farmer, who also worked as a mold boy when I was there. We shared many memories of other glass blowers. We recalled their eccentricities, habits, working conditions in the factory which were extremely difficult for men, but unbelievably hard for mold boys, ten and twelve years old. The factory was hot and the work timed for efficiency to produce containers in quantity and uniformity to meet the demand of the increasing population.

Several changes took place in the Manitoba Glass Factory within a few years. On my first trip to Beausejour in 1909, 1 was told the original glass factory was operated by Polish glass blowers who used pots for mixing glass and the European method to make the free blown containers.

Manitoba Glass Factory, Beausejour (1909-1911)

Source: Archives of Manitoba, John Reifschneider Collection 5, N17062.

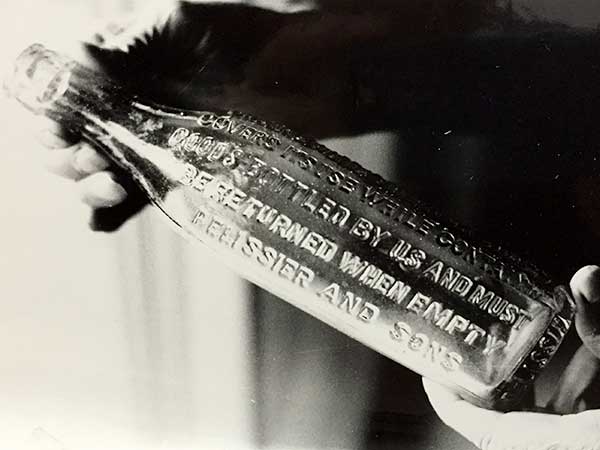

It is of interest to glass collectors to know the types of containers made in the Manitoba Glass Factory. During the time I worked in Beausejour, amber and green beer and soda bottles were produced. My brother Henry Reifschneider continued to work in the factory after I left in December 1911. The factory was changed over to semiautomation in early 1912. He told me that clear flint bottles shaped like ten-pins were made for a beverage firm. They made lids for Ball Brothers, clear medicine bottles and ink bottles.

Through friends in Beausejour I have several of the type of hand made beer bottles which were made when I was a glass blower. They are an amber bottle (McDonagh & Shea, Winnipeg), green bottle (E. L. Drewry, Winnipeg), and a green bottle (Pelissier and Sons, Winnipeg).

Beer bottle made at the Beausejour glass factory for Pelissier & Son, c1910

Source: Archives of Manitoba, John Reifschneider Collection 33, N17083.

The American system required a tank furnace constructed of fire-clay brick and fire clay, which could operate continuously for ten months of the year, providing glass-blowers, working in teams called “shops” with good quality working glass full time.

The tank furnace in the Manitoba Glass Factory was built semi-circular of fire-clay brick imported from Saint Louis, Missouri. A bridge of fire-clay was built lengthwise in the center of the tank, in the lower center of which was an opening or throat. The batch of raw material including mullet (scrap glass) was fed into the rear of the tank, the melted glass flowed through the throat into the front to form a pool of molten glass. The semi-circular side in front had openings called glory-holes, from which the glass blowers gathered the glass on pipes. The Manitoba factory had six shops operating when I was there.

Efficient operation of the furnace required that glass in weight (tonnage), removed by the glass blowers, be balanced with the amount in weight of the batch fed into the rear of the furnace. Tamarack wood was burned through a flu to make the gas from which flames played around and over the open furnace.

Crude oil heated the double glory hole unit which was separate and used in the final operation of making bottles. The factory had its own processing plant, a steam engine, to make electricity. It took about two weeks to start the furnace, due to the heat which required 3500 degrees. After the glass was in condition to work, it was kept at about 2500 degrees continuously during the season.

Each shop was a working unit of men and boys, working on two levels or benches, three journeymen glass blowers, one mold boy, one glory hole boy, and one carrying-in boy. The boys averaged ten to twelve years old. A former mold boy told of receiving one dollar a day for eight hours.

The glass blower heated the end of the blow pipe cherry red, gathered a small amount of glass on it, rolled it on the stone on the upper level, blew into the pipe to form a stem, dipped it into water to cool slightly and gathered more glass and blew again, working it on the stone. It was then placed in a hinged, two-way, air-cooled mold, which was clamped by the mold boy on the lower level. The glass blower blew again to form the bottle to shape. The mold boy took it out of the mold and set it on a table.

The glory hole boy placed it in a clamp the size of the bottle, ground off the rough glass on the neck and placed the bottle in the double glory hole to heat the neck cherry red. It then went to the gaffer seated on a bench. He had a tool to finish the neck, using a mix of charcoal and powdered rosin. The glory hole boy then put it on a paddle and it was carried to a conveyor belt in the annealing oven or lehr which was kept at 1300 degrees.

If the heat was too hot, the bottles stuck together and were ruined. If the oven was too cold, the annealing process failed.

The lehr was approximately eight by twelve feet and sixty feet long. It was heated by a separate heating unit. When the bottles reached the end of the conveyor, they were still warm, but ready for inspection, and packing.

A crude air conditioning system included a large pipe about twenty inches in diameter which circled the front of the furnace overhead. Smaller branch pipes about four inches with dampers extended to each shop. Men worked in light clothing because of the heat. Before each shift began working, buckets were filled with fresh water, molds were heated with glass and the stones were cleaned by rubbing with sandstone.

The factory operated two shifts in the twenty-four hours. Each worked eight hours with fifteen-minute rest periods during the first and second half of the shift. There was a one-hour lunch period. The men alternated, working one week days, one week nights. Glass blowers changed positions, one taking the gaffer (seated) position in the shop every fifteen minutes.

Wages were based on “piece work” with no limit on the amount a man could earn. Three journeymen working with good glass conditions could produce twenty-five gross or thirty-six hundred, fifteen ounce bottles during one eight hour shift.

A “spare” glass blower was not a regular, but often did very well, due to regular workers taking time off when earning abundantly.

Before the season began each year, during August, a meeting of the Glass Bottle Blowers Unions of Canada and the United States met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. They set up uniform wage scales, rules and regulations governing both glass blowers and factory owners. The regulations made it possible for workers to move freely from factory to factory within the United States and Canada. jobs were always available, skills of men uniform, and regulations standard. Glass blowers enjoyed prestige for earning the highest wage scale at that time. A mold boy’s ambition was to become a glass blower.

The Manitoba Glass Works in Beausejour, Manitoba started in 1904 was in operation ten years. During this brief period the factory began with the oldest known method of producing glass containers and closed with the modern American method of semi-automation, only a step from full automation. The complete cycle included several thousand years of glass container knowledge.

Page revised: 1 January 2016