Manitoba Pageant, Winter 1974, Volume 19, Number 2

|

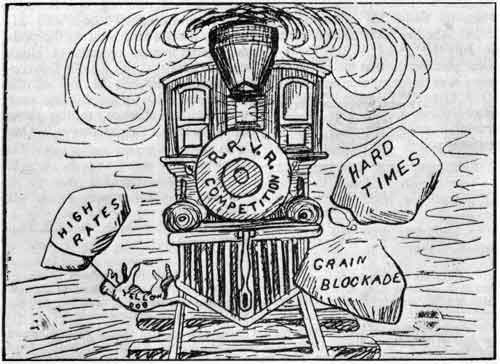

Our first grain shipping problems started 85 years ago. Grain transportation problems are nothing new to Manitoba farmers.

For more than 80 years they have been haunted by the spectre of rail or shipping tie-ups that threatened to slow down or halt completely the flow of crops to market. Last summer’s strike on the Vancouver docks is only the most recent manifestation of a problem that included for the past decade, an intermittent flood of complaints that not enough rail cars were available to handle the principal product of western farms.

The story goes back to 1887, the year Manitoba produced its first big crop and its first real challenge to the Canadian Pacific Railway’s monopoly of rail transportation in the West.

The federal government had guaranteed the C.P.R. 20 years without competition on the Prairies to compensate the company for the huge cost of building the line north of Lake Superior, but the guarantee was less than six years old when on July 2, 1887 Manitoba’s Premier John Norquay and a procession of dignitaries (including the mayor of Brandon) took part in the ceremonial first-sod turning for the provincially owned Red River Valley Railroad. The Premier told the cheering crowd of over one thousand spectators that the railroad would be finished “... ere the snow flies”.

The clearly stated purpose of the R.R.V.R. was to break the monopoly and give farmers an alternative method of getting their produce to the big markets in the United States.

The C.P.R. was not long in reacting. William Cornelius Van Home, its general manager, quickly reminded Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald of Clause 15—the monopoly guarantee—in their contract and Sir John as quickly obtained a writ disallowing the Manitoba venture.

The province ignored the writ and contractors continued clearing the right-of-way south from St. Boniface. Van Horne rushed to Manitoba and, using a special crew, pushed a spur line from the C.P.R.’s existing southern trackage right across the proposed route of the R.R.V.R. near Morris and ordered that the obstructing tracks be filled with the heaviest boxcars available.

Norquay ordered his work gangs to remove the obstruction and, in reply to the federal threat that regular troops would be sent to enforce the law, announced he would continue “... at the point of the bayonet”. A group of extremists threatened to blow up every bridge between Winnipeg and Montreal before the troops would ever get to Manitoba.

It was finance, not force that stopped construction of the new railway however. The province had trouble floating a special issue of railway bonds and by winter of 1887, work on the line stopped after $700,000 in public funds had been spent—a huge sum for those days.

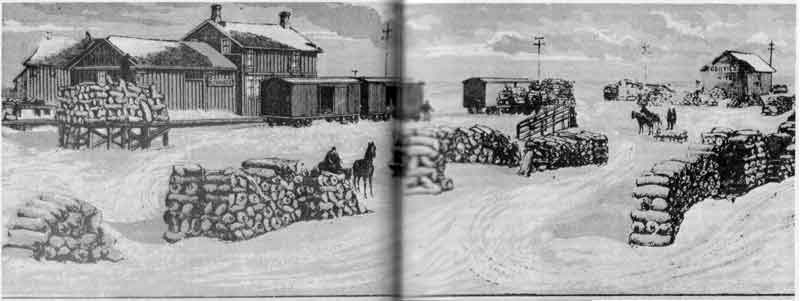

All the cost was not borne by the provincial treasury. By mid-December threshing of the 14 million bushel crop had been completed and everywhere within sight of the main C.P.R. line across Manitoba, enormous piles of wheat dotted the landscape. The C.P.R. was the only way the crop could be shipped and while the Norquay government still beat the drum for the Red River Valley project, Van Horne told reporters: “My impression is that the R.R.V. railroad is dead, at least for the present.”

In other words, “Ship with us, or else,” a veiled threat that was not made any more palatable by the fact that a short time earlier, the C.P.R. had increased its western freight rates well above those charged in the east. It now cost Manitoba farmers the staggering sum of 56¢ per bushel to get their wheat to the eastern seaboard as compared to 27¢ per bushel for Minnesota and North Dakota farmers (from Minneapolis) where railway competition existed.

True, Van Horne told the railway commission in December 1887 that protecting existing railways against the building of new lines was “an old world fallacy”, and supported wheat standard changes favoring Manitoba farmers.

But, it’s box-cars, not fine words that move goods and by mid-December, in spite of optimistic reports to the contrary, the harsh facts of a grain blockade were becoming evident as reports of a serious shortage of cars in many western Manitoba points seeped through.

A political crisis in Manitoba intensified the problem. Beset by problems within his party, Premier Norquay resigned the day before Christmas. His successor, D. H. Harrison suffered by-election defeats in January 1888, and turned the administration over to Thomas Greenway.

Norquay resumed the Conservative leadership and in reply to critics of his railway policy, reminded Winnipeg businessmen that when bonds were issued to finance the Red River Valley Railroad, a mere $1,100 was taken up locally, a far cry from the millions that were promised.

For Greenway’s Grits, it was a field day. They toyed mischievously with the threat of an election (which might have easily doubled their strength) goaded on by editorials in traditionally anti-Liberal newspapers that read like this: “The people are in a poor temper having before their eyes the paralysis of business caused by the grain blockade. There is no concession to popular sentiment in proposing to remove the monopoly in three years ...”

In Ottawa, Prime Minister Macdonald, although not a little disturbed over the fate of the Manitoba Tories, remained relatively cool about the rapidly deteriorating economic situation and stubbornly proposed that if Manitoba would “cease agitation” and “behave like an obedient child” it could be assured of an end to the monopoly by 1891.

Meanwhile, Manitobans were beginning to have doubts about some of the optimistic figures issued late in 1887 about grain shipments. The C.P.R. had said that 5,000,000 bushels of the current crop had been moved east, and 100 cars a day were hauling grain. But rumors of a virtual halt in grain transport were supported by facts and it was obvious to those who had counted heavily on a big cash return for the huge crop that there was a wheat blockade in effect.

More than a thousand cars of wheat were stalled somewhere around Port Arthur; the 87 cars of wheat that had left Winnipeg in mid-December had not yet reached points where they could be sold; farmers were being forced to accept ridiculously low prices just to get rid of their grain or be willing to “store” it in the open on the station platforms and main streets of the many delivery points where the elevators were plugged since the previous fall and only 25% of the box-cars asked for were supplied. Grain was bagged for shipment in those days.

Winnipeg and many of the small towns felt the effects acutely. Scores of businesses were declaring bankruptcy simply because honest customers were unable to transform their stocks of grain into cash.

Speaking out in protest to this incredible situation was one of Winnipeg’s leading businessmen, J. H. Ashdown of hardware fame, president of the local Board of Trade. (Incidentally, it was he who donated the shovel and the wheelbarrow for the sod-turning ceremony of the R.R.V.R.)

“If we are ever to succeed in this country ... we must have competition. The C.P.R. facilities are at present very inadequate and their desire seems to be to throw the work over to a more convenient season when they hope to save money by shipping the grain over the lake route.”

Voicing the sentiments of Winnipeg citizenry in general was a prominent local clergyman—Rev. R. Pitblado of St. Andrews Presbyterian Church. He firmly denounced the C.P.R. and monopoly stating that “Monopoly will surely never choke itself by allowing millions of bushels of the best wheat in the world to mould in the granary or rot in the field ... right will triumph, truth will prevail ...”

As winter went on and economic woes multiplied, Manitobans became more annoyed. The last straw was when a passing train struck a sagging pile of grain sacks at Deloraine, ripped them open and spilled grain all along the line.

Casual talk of a commercial union with the United States now changed to serious consideration of a political union or annexation and the popular disenchantment finally forced Premier Greenway and his attorney-general, “Fighting Joe” Martin to go to Ottawa seeking a federal abandonment of the monopoly policy.

Although they were wined and dined by Sir John Macdonald, Greenway and Martin were, apparently, studiously ignored by C.P.R. officials and left the capital in anger. More alarmed than surprised at their departure, Sir John urged them, by telegram, to return immediately and promised a conditional settlement. Said he: “I have known Manitobans for some time ... but ... I think it would be unsafe to reckon on the present storm blowing over with the difficulties unadjusted.”

Of course, giving in to a provincial administration of Liberal hue didn’t sit too well with Macdonald and his Conservatives, but the British government, which still had considerable influence on Canada’s internal affairs, feared a repetition of the 1885 rebellion, and ordered Sir John to meet Manitoba’s demands—unconditionally.

Ottawa agreed (somewhat reluctantly) to extricate itself from the monopoly clause, in its contract with the C.P.R.—but had to pay the railway company $15,000,000 for the breach of contract.

Greenway and Martin came home to a hero’s welcome.

In Deloraine, the assistant superintendent of the C.P.R. suddenly turned up in April because, he said, he had heard “rumors of a car shortage there.” He only stayed an hour, possibly because he was unwilling to face angry farmers and incensed grain buyers, but within a few days, enough box-cars were made available so that piles of wheat on the street were a thing of the past.

The grain blockade was over.

The West was no longer at the mercy of a single railway company.

However, the bill that could kill the monopoly could not erase the visceral resentment that—understandably—lay in the hearts of C.P.R. employees of high and low rank who probably feared that competition for their employer would mean the loss of employment through lost revenue.

These feelings surfaced when the Manitoba government attempted, in September of 1888, to cross the C.P.R. main line at Headingly with its new line from Winnipeg to Portage la Prairie. The C.P.R. workmen refused to allow them near their track. When the Manitoba railway’s works crew constructed a crossing under cover of darkness in defiance of the C.P.R. employees’ opposition, the latter tore it out and carted it off as a “prize of war”. Immediately both sides mobilized for a pitched battle with many local farmers (some of them brandishing pitch forks) siding with the Manitoba railway employees. Locomotives stood ready with live steam. For two weeks the opposing sides dared each other to make the first move. But then ... that is another story.

Page revised: 20 July 2009