Manitoba Pageant, Winter 1972, Volume 17, Number 3

|

In the early 1870s, my grandfather, James Johnston, and his family were living at a small place called Billings Bridge Village, which is today a suburb of Ottawa, Ontario. In 1879 he accepted an appointment with the Indian Affairs Branch and went to Crow Stand, Fort Pelly, North West Territories, as a farm instructor. On the trip west he was accompanied by his two sons, Robert and Adam, and a daughter, Margaret. They travelled by rail to St. Paul and then came over the Pembina Trail with wagons, Red River Carts, horses, and oxen. From Winnipeg they went northwest over the Carlton Trail (which father always called the Dawson Trail), and then by the Pelly Trail to Fort Pelly.

They left Winnipeg in July 1879 with one wagon, three Red River Carts, two horses and four oxen. Since grandfather was going to Crow Stand on a government assignment, the Dominion authorities in Winnipeg supplied him with enough salt pork and groceries for the trip. During the thirty-two days it took to go from Winnipeg to Crow Stand, their diet consisted entirely of salt pork and flapjacks. They had trouble crossing small streams which were in flood and it took them a whole day to get across the Little Saskatchewan (Minnedosa) River; all the supplies being ferried over on a raft made of the four wagon wheels, the horses and oxens swimming across.

When they arrived at Crow Stand they made a small shack of logs and packed prairie grass on the roof poles to keep out the rain. Their food for the balance of the year was brought in a month after their arrival, and it consisted of 52 sacks of flour, 13 barrels of pork (each weighing 200 pounds), 3 chests of tea (each weighing 50 pounds), 3 barrels of granulated sugar, 100 pounds of baking powder, 4 barrels of dried apples, and bags of raisins, currents, and boxes of rice and dried, pressed vegetables.

There were over two thousand Crees in the vicinity of Crow Stand, the three chiefs being "Caty" (Presbyterian), "Keys" (Church of England), and "Keetchako" (Roman Catholic). The Indian school was taught by a halfbreed named "Cub" Mackay. Most of the Indians refused to do farm work, and they hunted for game only when forced to do so by hunger. The Indian women did most of the farm work as well as their traditional native tasks. They threshed the grain with flails and cleaned turnips and other vegetables for stews, in which sometimes even entrails and rawhide were mixed.

As the buffalo were disappearing rapidly at this time, food was a constant concern of the Indians, and even the little Indian lads, six to ten years of age helped in an ingenious way to provide their families with food. They would whittle dozens of willow branches as thin as lead pencils, sharpening one end of each, then plant them firmly in the ground in the rabbit runs, with the points slanting in the direction from which the rabbits generally ran. Then the youngsters would go into the bush barking like dogs and chasing the rabbits along the runs. They rarely came back empty-handed, sometimes getting as many as a dozen rabbits in each drive.

Boggy Creek Stopping House (circa 1900) seen through railing of bridge over Boggy Creek on Pelly Trail.

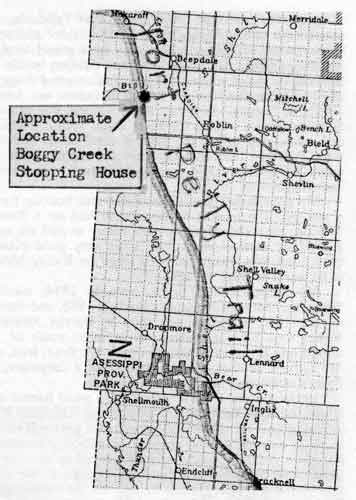

After four years at Crow Stand, Fort Pelly, the teaching assignment petered out and my grandfather and his three children moved to Boggy Creek (north of Roblin). Here they were joined by my grandmother and the rest of the family, there being ten children in all. They built their log home at the point where the Pelly Trail crossed Boggy Creek, a tributary of the Upper Assiniboine. My grandfather was known throughout the district as "Boggy" Johnston, and his home was called the "Boggy Creek Stopping House." Here travellers could secure overnight accommodation and meals long before the days of rural hotels and motels. At this time the C.P.R. had reached Moosomin and supplies were picked up from this point, the overland trip usually took two weeks, two trips being made each year.

My grandfather sawed the beams and flooring for his home by using a saw pit. The logs to be sawn were laid on a frame over the pit and with one man above and another below to pull the saw up and down on a carefully marked chalk line, some very good planks were laboriously hewn from logs which had been felled on Riding Mountain or sometimes as far north as Duck Mountain.

My father, Robert Bruce, born in 1854, married Harriet Amelia Simmons, widow of Alexander Reid, in 1885, and there were nine children of this union, as well as one child by Harriet Amelia's former marriage. Father took up a homestead three miles south of Binscarth and later moved into Binscarth where he operated a flour, feed, and bakery business. My father's brother, Andrew, who was a carpenter, built the store and bakery which were attached to our home.

Uncle Andrew lived at Asessippi, a small hamlet situated in the valley where the Pelly Trail crossed Shell River. The Shell River was dammed at Asessippi and Mr. Henry Gill operated a grist mill there and ran a general store as well. When the railroad bypassed Asessippi, almost all the inhabitants, including uncle Andrew, moved to the new town site of Roblin. These first citizens of Roblin lived in tents to start with, and after they had obtained permanent lots by auction, the auctioneer being T. C. Norris, later Premier of Manitoba, they built their homes, many of log construction and a few of milled siding.

When I was a boy I remember going with my father by wagon and team to Russell where two of my aunts were living. Our next stop was at the Brooks Stopping House, about twelve miles north of Russell. This was a very interesting place, particularly for a small boy, for Mrs. Brooks was an expert taxidermist, and one room of her home was filled with mounted specimens. There were literally scores of them, from the great whooping crane to the smallest of finches. Just a few years ago, sometime in the 1960s, I seem to recall, a granddaughter of Mrs. Brooks told me that this fine collection had gone to a museum in the United States. What a loss to Manitoba and Canada. Mr. Brooks had come west from Georgetown, Ontario in 1881, and in the following year he met Mrs. Brooks and their four children at Moosomin. From this point they made the journey to their homestead by ox teams, but at the Asessippi hill the descent was so hazardous and steep that the wagons were slowly lowered down by block and tackle.

As a young lad I remember seeing Pauline Johnson, the Mohawk Princess, in Binscarth. She had come to give one of her recitals. This would be about 1900, and at the time I was working in Dr. Lanigan's drug store, where the tickets for Miss Johnson's concert were being sold. She once told Ernest Thompson Seton, "My aim, my job, my pride is to sing the glories of my own people." And this brings to mind the fact that Ernest Thompson Seton, while employed as a naturalist with the Government of Manitoba, made a nature tour of the Asessippi area, and in his autobiography he mentions staying at the Boggy Creek Stopping House and meeting my grandfather, to whom he applies his well known local name "Boggy" Johnston.

|

|

|

James Johnston |

Sarah Jane Johnston |

See also:

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Asessippi Townsite (RM of Shellmouth-Boulton)

Page revised: 9 December 2012