by Cary Miller

University of Manitoba

|

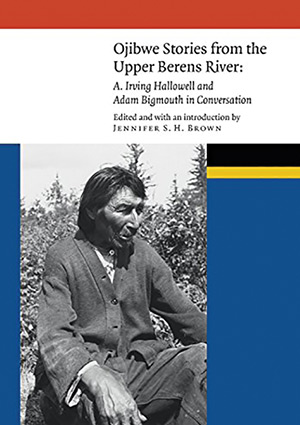

Jennifer S. H. Brown (ed. & intro), Ojibwe Stories from the Upper Berens River: A. Irving Hallowell and Adam Bigmouth in Conversation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press and the American Philosophical Society, 2018, 188 pages. ISBN 978-1-4962-0225-3, $66.31 (hardcover)

Over the past two decades, Jennifer S. H. Brown has been engaged in bringing the work of A. Irving Hallowell to a new generation of scholars. Hallowell wrote primarily on Anishinabe/Ojibwe communities based on his fieldwork on the Berens River in the summers of 1938 and 1940s, a work that is richly ethnographic in the tradition of his instructors Frank G. Speck and Franz Boas. He has left an unusually rich legacy in the field through students such as Regna Darnell, Anthony F. C. Wallace, and Ray Fogelson. While Hallowell’s work is sometimes contextualized by the psychological inter-pretations of the ‘culture and personality’ approach he employed, his original field work remains an invaluable resource for scholars and community members today.

Over the past two decades, Jennifer S. H. Brown has been engaged in bringing the work of A. Irving Hallowell to a new generation of scholars. Hallowell wrote primarily on Anishinabe/Ojibwe communities based on his fieldwork on the Berens River in the summers of 1938 and 1940s, a work that is richly ethnographic in the tradition of his instructors Frank G. Speck and Franz Boas. He has left an unusually rich legacy in the field through students such as Regna Darnell, Anthony F. C. Wallace, and Ray Fogelson. While Hallowell’s work is sometimes contextualized by the psychological inter-pretations of the ‘culture and personality’ approach he employed, his original field work remains an invaluable resource for scholars and community members today.

In 1990 and 1996, Jennifer Brown ordered photocopies of the folders containing transcripts of the stories that Gisayenaan, or Adam Bigmouth, shared with Hallowell from his papers, which are housed at the American Philosophical Society Archive. As Hallowell usually only pulled limited excerpts from his original notes, this publication represents the first time that the stories of Adam Bigmouth are published in their entirety. Because these stories were collected during the summer, when aadizookaanag (myths and legends with religious content) were not told, these stories are all dibaajimowin (narratives about people you know). Still, as many of these stories are about Adam’s father Ochiibaamaansiins (Northern Barred Owl), who was a highly regarded healer during the early to mid-19th century, they do contain a great deal of information about the religious world of the Anishinaabe. Several of the stories focus on topics such as Windigos, healing, love medicine and bad medicine.

In collecting and publishing these stories, Brown has added a great deal of material that adds to their value. She frames the stories with an introduction to the speakers as well as to their family members appearing in the narratives, provides the cultural and historical context in which the stories were collected, and offers an afterword that contextualizes the ways in which “The stories and memories of Adam Bigmouth open a window onto the lives and relationships of four generations of Ojibwe people on the upper Berens River,” and especially to “their culturally constituted world,” in Hallowell’s terminology. Further, she notes that most of the original translations would have been accomplished through collaboration with William Berens, and has included much of Hallowell’s marginal content concerning the stories, lightly editing them for readability. A glossary of Ojibwe personal names used in the text is another very helpful inclusion.

That said, as with every published work, there are a few things that could have made this work even more valuable. While the identification of the family members and discussion of their relationships to one another was helpful, a genealogical chart of these relationships would have been easier to reference while reading the stories themselves. Also, some stories were omitted as redundant or fragmentary, which always leaves the reader wondering what else was there. But then I suppose that perhaps gives good researchers in this field the possibility of further gems to be mined from Hallowell’s papers. Also, while Brown did lightly edit the stories for clarity, occasionally it is difficult to determine the antecedent of third person pronouns, although this is likely a result of the ambiguity of third person pronouns in the Anishinaabe language.

As Brown notes, this book is a wonderful companion to Orders of the Dreamed, which she also edited. The two books deal with many of the same topics and demonstrate a cultural continuity that is both geographic and temporal. The essays also reveal a great deal about the kinship structure of several inter-related families along the Berens River. Its readability and contextualizing essays lend it well to classroom use.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 25 April 2021