by Paul G. Thomas

University of Manitoba

|

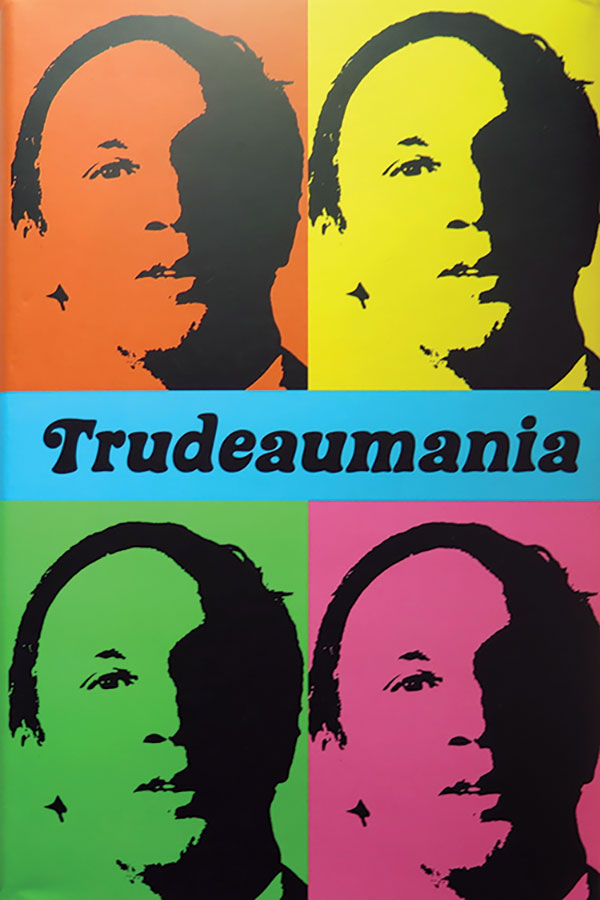

Paul Litt, Trudeaumania. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016, 412 pages. ISBN 978-7748-3404-9, $39.95 (hardcover)

This is a very good book on the rise to power and the governing style of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Canada’s fifteenth Prime Minister. Published in 2016, the book richly deserves the praise and awards that it has already received. When the author Paul Litt, a history professor at Carleton University, began research in 2003, there was already a huge volume of material on Trudeau. So it took imagination, ingenuity in terms of methodology, and perseverance over a decade to produce an original, perceptive analysis of the historical and contemporary cultural context that gave rise to the phenomenon of Trudeaumania. Presented in an introduction, ten chapters, and a short conclusion, the main argument of the book is that while an array of both historical trends and more short-term events set the stage for Trudeaumania, it was the media that brought the phenomenon to life.

This is a very good book on the rise to power and the governing style of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Canada’s fifteenth Prime Minister. Published in 2016, the book richly deserves the praise and awards that it has already received. When the author Paul Litt, a history professor at Carleton University, began research in 2003, there was already a huge volume of material on Trudeau. So it took imagination, ingenuity in terms of methodology, and perseverance over a decade to produce an original, perceptive analysis of the historical and contemporary cultural context that gave rise to the phenomenon of Trudeaumania. Presented in an introduction, ten chapters, and a short conclusion, the main argument of the book is that while an array of both historical trends and more short-term events set the stage for Trudeaumania, it was the media that brought the phenomenon to life.

The book is based on impressive research. Its main sources are media reports and commentaries contemporary to the period when Trudeau was emerging as a political actor, and during his years as prime minister. To offer a deeper understanding of these sources, Litt draws upon the more theoretical insights from disciplines such as communications studies, history, journalism, political science, and sociology. More “academic” readers will want to consult the lengthy endnotes section that adds further depth to the analysis. Excellent scholarship does not make this a dull book. The writing is highly readable, with only the minimum amount of specialized language employed to present the analysis. There are lots of vivid anecdotes and quotations. Humorous chapter titles, the use of editorial cartoons, and the inclusion of many black and white photos add to the entertaining quality of the book.

The label “Trudeaumania” was coined by right wing columnist Lubor Zink of the now defunct Toronto Telegram in order to compare the shallow and emotional appeal of Trudeau to the infatuation of teenagers with the Beatles. Litt acknowledges that interpreting the meaning and measuring the impacts of Trudeaumania is more an exercise in informed speculation than straightforward empirical analysis. The phenomenon was about far more than just the individual; it reflected the confluence of a wide range of trends and developments of the late 1960s. This includes postmodernism and the decline of deference, the emergence of a countercultural movement within society, the sexual revolution, and the rise of Canadian economic and cultural nationalism. It also includes Trudeau’s personality, style and physical appearance, his skillful use of liberal ideas to connect with these cultural trends and, most importantly, reliance on political marketing and the media, especially television, to project an exciting image of a new “hip” leader who lifted the country out of the doldrums of the “tweedledee-tweeddledum” politics of the Diefenbaker-Pearson era. Trudeau’s image, Litt writes, “was an unstable, evolving montage of prominent features of sixties culture and nationalist ambition” (p. 181).

The emergence of Trudeau as a political figure was an exciting time for Canadians. I witnessed the excitement at a shopping mall in Winnipeg during the 1968 election when he arrived in an open sports car and was greeted with screams from adoring crowds. Many, but not all, of the screamers were too young to vote.

Trudeaumania did not transform the political landscape. The 1968 election was not what political scientists call a realigning election, in which there is higher than usual voter turnout and where a dramatic, enduring shift in party loyalties takes place. Turnout in 1968 was 76 percent—one percent above the previous election and well below the average turnout of the previous four general elections. The Liberals won a solid majority in the House of Commons, but this was based on only 46 percent of the votes. Support was not evenly distributed nationally; Trudeau won just seven of thirty-two seats in the Atlantic region and twenty-seven of sixty-eight seats in the West.

Canada is a country of considerable social diversity and significant regional differences, including the fundamental political fact that the province of Quebec is the centre of francophone political life. The rise, in recent decades, of Indigenous pride and stronger First Nations organizations has added to the challenges for political leaders of mainstream governments. Achieving a strong shared national identity has proven to be exceedingly difficult. Litt describes contemporary Canada as a “simulation” (that is, simulation of a nation), and the only kind of nation possible under the circumstances (p. 28). From Confederation onward, political parties that aspired to govern nationally have relied greatly upon leadership appeal and downplayed class issues and ideologies that were seen as too divisive for a fragile, fragmented country. Trudeaumania, Litt notes, had its greatest initial appeal among the better educated managerial class, who were impressed with the rationalistic and pragmatic approach of a cerebral prime minister.

Trudeau surfed to power on his image in 1968, but he nearly lost the 1972 election when the Progressive Conservatives increased their share of the popular vote by 4 percent compared to a 7 percent decline for the Liberals. As leader of the Progressive Conservatives, Robert Stanfield lacked Trudeau’s charisma, but he came within three seats of defeating the Liberals. Left with very few seats in the West and the Atlantic region, Liberals could hardly claim to be a truly national party.

In electoral terms, therefore, the mania for Trudeau was never as wide or as deep as nostalgic memories might suggest. Many Canadians, especially the younger generations, found him to be an enticing political leader, while other voters respected him for his intellect. Still others mistrusted him, and a small minority despised him. Leadership is clearly important in political life, but studies argue persuasively that we often exaggerate its importance to electoral success (see, for example, Archie Brown, The Myth of the Strong Leader: Political Leadership in the Modern Age, London: Basic Books, 2014).

From 1972–1974, as prime minister of a minority government Trudeau had to cater to the demands of the New Democratic Party that held the balance of power in the House of Commons. Even though Trudeau was highly intelligent and had strong convictions on certain public policy matters, most notably national unity, he was forced to be politically pragmatic and opportunistic in order to survive politically. Political managers in the backrooms of the Liberal Party used their experience and skills to maintain the party’s role as the natural governing party of Canada.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, politics was a mediated activity in which most of us, most of the time, were spectators to the process. We received our impressions of leaders and events through the media, mainly through nightly television newscasts. Liberal strategists were very effective in choreographing and staging political events to maximize favourable coverage. Also, in this period, leadership character and experience were being displaced as factors in voter choices by personality and style. By his exotic appearance, style, detached demeanour, and unpredictable behaviour, Trudeau was “typecast” for the age of celebrity television. His image conveyed that most valuable virtue of the era: authenticity. Litt argues that the Liberals did not foist Trudeau on the media. Over time, however, many media personalities came to believe they had been used by the Liberals to help them sell a candidate and prime minister.

As a media phenomenon, Trudeaumania was ephemeral for many Canadians. A more enduring impact came through the political philosophy that Trudeau had developed during a lifetime of academic study and his more applied thinking derived from fighting conformist and repressive regimes in Quebec during the 1950s. He rejected extreme forms of collectivist thinking and nationalist sentiments. He insisted on the need to respect diversity and to uphold individual rights. Over his fifteen years as prime minister, his thinking translated into such important, concrete public policy measures as the Official Languages Act, multiculturalism, and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. His ideas changed some of the foundational assumptions of the political culture of the country.

The short conclusion to the book is mainly a summing up and an honest acknowledgement of the limits of the analysis. Just before the book appeared, Justin Trudeau became prime minister, causing Litt to suggest that the excitement of Trudeaumania might be partially revived in his son. Of course, the political, economic, social, and technological context in which the son achieved political success differed significantly from the context of the 1970s and 1980s when his father burst on the political scene. Most importantly, the media environment has changed drastically. Pierre Trudeau relied on a limited number of television networks and newspapers to gain his profile and popularity. Today, the media environment is much more fragmented, and social media provides the potential for leaders to make a direct connection with voters, rather than relying solely on mainstream media to convey their messages and foster their images. Like his father, Justin has inspired engagement with the political process by many Canadians, but he seems more emotionally accessible and less detached than his father. One hopes that one day there will be another book, equal in quality to Litt’s contribution, that will compare the leadership of father and son.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 7 January 2021