by Patricia Harms

Brandon University

|

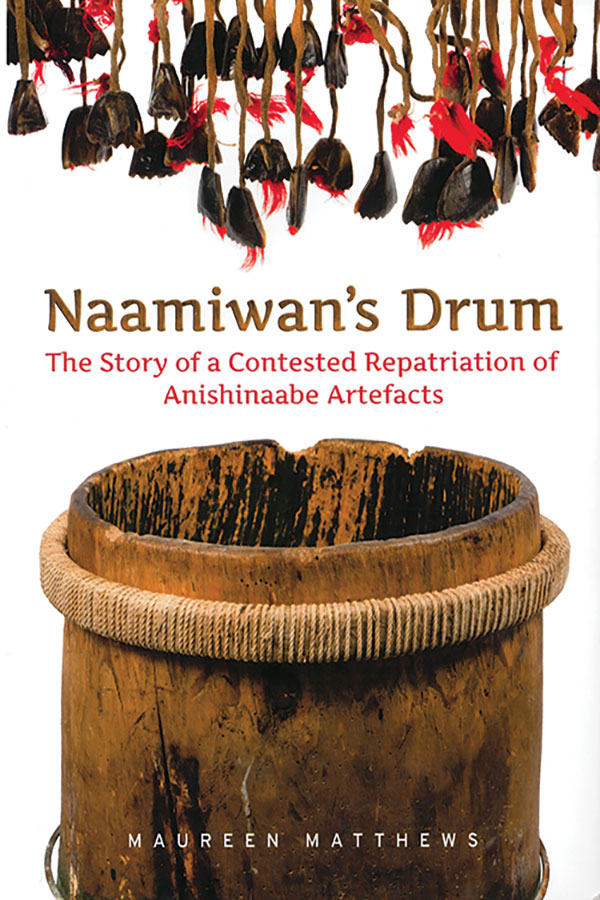

Maureen Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum: The Story of a Contested Repatriation of Anishinaabe Artefacts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016, 325 pages. ISBN 978-1-4426-2826-7, $34.95 (paperback)

Naamiwan, a revered Anishinaabe medicine man, lived along the greater Berens River system that flows from western Ontario to Lake Winnipeg, in the small extended family community of Pauingassi. His life spanned almost a century from 1851 to 1944, and his reputation grew as he aged. Following the tragic death of his beloved grandson, Naamiwan experienced a deep spiritual transformation, and the healing ceremonies that subsequently developed became known throughout the region. The drums and religious tools that he created were passed down to his son Waanacens and grandson Omishoosh who took on leadership roles in their own right, although neither man assumed the prestige of Naamiwan. A significant number of these ceremonial tools and drums were eventually housed in a museum at the University of Winnipeg. During the 1990s, these artefacts were removed by an Anishinaabe group, Three Fires Midewiwin Lodge, from Wisconsin. The story of these ceremonial artefacts and their life at Pauingassi, in Winnipeg, and then finally in Wisconsin is examined in Maureen Matthew’s new book Naamiwan’s Drum.

Naamiwan, a revered Anishinaabe medicine man, lived along the greater Berens River system that flows from western Ontario to Lake Winnipeg, in the small extended family community of Pauingassi. His life spanned almost a century from 1851 to 1944, and his reputation grew as he aged. Following the tragic death of his beloved grandson, Naamiwan experienced a deep spiritual transformation, and the healing ceremonies that subsequently developed became known throughout the region. The drums and religious tools that he created were passed down to his son Waanacens and grandson Omishoosh who took on leadership roles in their own right, although neither man assumed the prestige of Naamiwan. A significant number of these ceremonial tools and drums were eventually housed in a museum at the University of Winnipeg. During the 1990s, these artefacts were removed by an Anishinaabe group, Three Fires Midewiwin Lodge, from Wisconsin. The story of these ceremonial artefacts and their life at Pauingassi, in Winnipeg, and then finally in Wisconsin is examined in Maureen Matthew’s new book Naamiwan’s Drum.

This fascinating study defies simple categorization, being at once a detective novel; an in-depth, ethnohistorical analysis of the still vibrant Anishinaabec language; an academic examination of repatriation; and a highly sensitive exploration into the meaning of colonization, religion, and intracultural relationships. Matthews employs several academic models in her desire to understand the role of Naamiwan’s ceremonial tools within Pauingassi culture and the reasons for their removal by another Anishinaabe community. She purposely uses the word artefact to discuss the items themselves, and she implements Alfred Gell’s theory “which situates art objects, not as signifiers of culture, but as actors in social networks” (p. 203). These artefacts act as other-than-human persons with agency: the capacity to act, and a degree of intentionality. As she uncovers their creation and life within Pauingassi spirituality, Matthews considers the question of animacy, going deep into the meaning of language, its uses over time, and what it means to be alive. Matthews explains her intentional employment of these models because they are in sympathy with Ojibwe metaphorical thinking about the agency of ceremonial objects. It is a model that postulates personhood for objects and stands outside of the colonial and coercive museum paradigms (p. 17).

At the core of this story is also the relationship between Anishinaabe groups themselves. As the most sensitive element of this story, Matthews explores the historical and contemporary nature of these intracommunity dynamics, and she handles this very complex part of the story with unusual kindness, intellectual curiosity, and a willingness to be uncomfortable with what her sources reveal. Despite her personal involvement in the discovery that the tools had been removed from the University of Winnipeg, Matthews engages with members of the Three Fires that assumed custody of the ceremonial objects. Within this inquiry, Matthews employs the urgent question, ‘What is traditional?’ in her search for the missing artefacts. She examines the differing meanings of traditional between Pauingassi residents and Three Fires. This is perhaps the most critical question Matthew raises and in so doing, allows the reader to move past judgement and towards understanding of all perspectives.

This inquiry exposes the rationale used by the Three Fires group to remove artefacts that are not a part of their community history. In making the claim that their practice of traditional spirituality led them to remove the artefacts from the custody of the museum and thereby the community of Pauingassi, Matthews argues that the Three Fires members effectively privileged one type of Ojibwe ceremony over against another’s, in effect disenfranchising their northern cousins. Matthews reminds the reader that there is no single Ojibwe culture and challenges the assertion of Three Fires that Naamiwan’s descendants were not practising their culture in the appropriate traditional manner. She concludes, “[T]his repatriation study shows that grouping Ojibwe people according to their linguistic/tribal affiliation and assuming a homogenous cultural zeitgeist is profoundly misleading” (p. 15). The people at Pauingassi have always practised their socio-cultural traditions within their own parameters, prohibiting or accepting outside influences as it suited their cultural, physical, or spiritual needs. Matthews suggests that to understand the cultural and historical complexity within Ojibwe culture is to understand it as islands of Ojibwe experience. To misunderstand this critical element is to miss the asymmetrical power relationships at the heart of this inadvertent but telling instance of cultural intimidation (p. 172). She extends this analytical question to the University of Winnipeg personnel, claiming that “the university became complicit when it chose to accept ‘traditional’ claims [of one group] and ignore an evident disparity in power relations within the greater Anishinaabe community” (p. 175).

This book is about surprises and silences, while diving deep into the Anishinaabec language and its practitioners. Matthews is able to reach such deep linguistic and cultural understandings of all perspectives within this complex story through her use of the Anishinaabec language. Here she acknowledges the collaboration with translator Roger Roulette, himself a native Anishinaabec speaker. Transcribing conversations with Omishoosh, other community members, and leaders of Three Fires, the book provides parallel English and Anishinaabec texts. The careful textual reading by Matthews and Roulette provides the reader with an unusual depth of socio-cultural understanding. The vibrant spiritual concepts that leap from these pages cross the generational and cultural divide between the reader and the actors within the story. In so doing, that divide raises some rather astonishing and sometimes uncomfortable questions including: What is animate and inanimate? What is the role of museums and community agency? What is the complexity within broad cultural groupings? Who has voice here? How have spirituality and colonialism interacted? This work will no doubt become a standard by which repatriation and perhaps even cultural and community studies are judged.

While this book makes invaluable contributions, perhaps its most significant impact is to reveal elements of the Pauingassi community itself, its history, the life of Naamiwan, and the rich spiritual practices that are embodied within his drum. As Matthews notes, “Maybe this was the drum’s fate all along; maybe fame and notoriety are his destiny. If the drum’s agency is derived from his relationship to Naamiwan and if Naamiwan stirs from the land of the dead from time to time, sudden lurches in register and meaning are astonishing but not surprising” (p. 247). If this is the only accomplishment of Matthews’ extraordinary work, then from my own perspective, as someone who belonged to the Pauingassi community as a child, her effort is well worth it.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 3 November 2022