by Dianne Dodd

Parks Canada

|

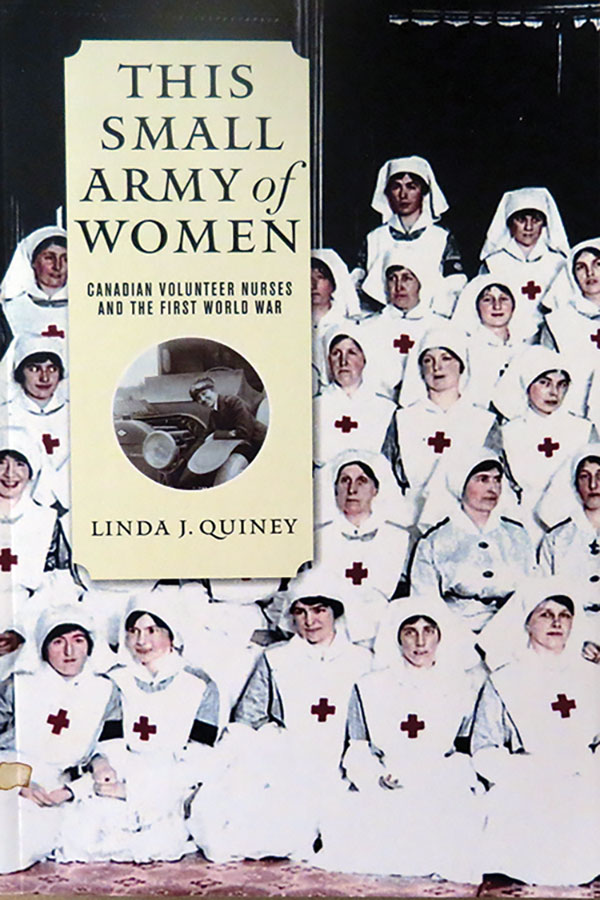

Linda J. Quiney, This Small Army of Women: Canadian Volunteer Nurses and the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2017, 320 pages. ISBN 978-07748-3071-3, $95.00 (hardcover)

Linda Quiney’s book adds to the growing historiography on nursing and health care work during the First World War. Her comprehensive review promises to “bring the work and experience of a ‘small army’ of Canadian and Newfoundland women out of the shadows to claim their rightful place in the mainstream histories of the war” (p. 14). Quiney’s study focuses on the Volunteer Aid Detachment nurses (VADs) who served overseas as assistant nurses working under the supervision of trained nurses to help care for patients. She also focuses on ambulance drivers who transferred injured patients from field stations to hospitals and maintained the vehicles. Quiney also discusses the VADs who served in the aftermath of the Halifax Explosion of 1917 and during the Spanish Influenza pandemic, two high-profile events that enhanced their profile.

Linda Quiney’s book adds to the growing historiography on nursing and health care work during the First World War. Her comprehensive review promises to “bring the work and experience of a ‘small army’ of Canadian and Newfoundland women out of the shadows to claim their rightful place in the mainstream histories of the war” (p. 14). Quiney’s study focuses on the Volunteer Aid Detachment nurses (VADs) who served overseas as assistant nurses working under the supervision of trained nurses to help care for patients. She also focuses on ambulance drivers who transferred injured patients from field stations to hospitals and maintained the vehicles. Quiney also discusses the VADs who served in the aftermath of the Halifax Explosion of 1917 and during the Spanish Influenza pandemic, two high-profile events that enhanced their profile.

Quiney’s volunteer nurses who went overseas to assist trained nurses, largely in British hospitals, were part of a larger group of some 2,000 Canadian VADs who served through the St. John’s Ambulance Society and the Canadian Red Cross Society from 1916 until the end of the war. There were also some Canadian women who joined the British VADs. The study, among other things speaks to professional tension between volunteers and trained nurses. In overseas hospitals run by the Canadian Army Medical Corp (CAMC), VADs were not permitted to serve. Rather, nursing care was provided by trained, i.e., professional, nurses, called Nursing Sisters who also held officer rank in the military. They served under Matron Margaret Macdonald who, with an eye to protecting the professional status of the emerging nursing profession, kept out the volunteers, except in non-nursing care in Canadian military hospitals. That was not the case in British hospitals, nor in convalescent hospitals run by the Military Commission in Canada for returned soldiers, where many Canadian VADs served.

Enlivened with quotes from the women themselves, This Small Army sheds light on these volunteers, their background, war experience, work and colleague relationships, the health impact of their service, and where their lives took them after the war. We learn, for example, that some VADs did auxiliary nursing chores that would not have been possible in peacetime, such as helping to change dressings, and applying and monitoring poultices. They were also sometimes assigned the important chore of watching over amputation cases, in which there was a great danger of hemorrhage.

The book also highlights some of the tensions between trained and volunteer nurses, as well as the ever present Imperial/Colonial tensions between Canadians and Brits. Indeed Quiney’s study quite clearly points out that Canadian VADs were very different from the upper class, often titled ‘British VADs,’ as exemplified in Vera Brittain’s postwar writings, which have formed a longstanding public perception. Such distinctions hearken back to an earlier time, when the importance of class was greater than that of education as a marker of standing. The writings and letters of the VADs shed light on tensions between volunteer and trained nurses, the latter guarding carefully their tenuous hold on professionalism. Quiney makes the point that once the volunteer nurses came home, only four of the VADs went into nursing as a profession, proving unfounded the fears of nursing authorities that volunteers would flood the profession and try to use their war experience as a ‘backdoor’ into nursing. Still, the concept of ‘voluntary’ nurses, and the associated idea that all women are by nature caregivers, posed a real threat to the educational and professional accreditation that nursing was seeking at this time.

The book adds to the growing historiography on military nursing and health care. Recent studies, such as Cynthia Toman’s Sister Soldiers of the Great War: The Nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (UBC Press, 2106) and Sarah Glassford and Amy Ward’s A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War (UBC Press, 2012) outline Nursing Sisters and other female volunteers’ roles during wartime. The book also adds to the considerable literature on British nurses and VADs. Together they show that, despite the professional divisions between Nursing Sisters and VADs, their stories read as remarkably similar. VADs who did nursing work were predominantly middle-class women with similar educational backgrounds in teaching, clerical work, etc. Many had attended university, and their parents tended to be merchants, clergy, high-ranking professionals, and community leaders. Almost all were unmarried. Just like the nurses, VADs who did nursing work, experienced difficult working conditions due to harsh weather, accommodation, lack of food, periodic bouts of overwork and exhaustion, and the emotional strain of caring for the critically ill. They also saw horrific injuries and medical conditions, and were occupied with comforting the dying. Like Nursing Sisters, some of the VADs became ill as a result of the physical and emotional strain. Seven VADs died as a result of exposure to illness, specifically the Spanish Influenza pandemic. Some were serving in Canada when they died. By comparison, it should be noted that of the more than sixty Nursing Sisters who died as a result of their wartime service, one third died from illness, half of that number due to the Spanish flu. [1] However, fewer VADs appear to have served for the four to five years that some Nursing Sisters served.

Voluntary nurses and Nursing Sisters seem to have had similar reasons for going overseas. Besides patriotism, they wanted to travel, to have adventures, and to be close to their brothers or fiancés who were fighting overseas. Once there, both groups took advantage of opportunities to travel, and both, following the expectations of their gender, organized social events for staff and patients such as Christmas parties, concerts, and teas. Being a VAD or a Nursing Sister gave women a chance to leave home and to see the world, a chance that few women, except for the very wealthy, enjoyed. Still, as dutiful daughters, VADs and Nursing Sisters alike observed gender norms and came home when their families called them. And, much like soldiers, they valued their experiences, despite any hardships they endured. For example, Agnes Wilson noted, “Oh it was a marvellous experience! Really, I wouldn’t have missed that for anything!”

This Small Army tells a fascinating story and adds to the military health literature. However, it should be remembered that Quiney’s “small army” constituted only about one quarter of all VADs—those who did overseas nursing and drove ambulances, two of the more ‘romantic’ wartime roles for women. There were approximately 1,500 other VADs who cared for soldiers with long-term injuries in military convalescent hospitals across Canada and Newfoundland, cared for civilian flu and Halifax Explosion victims, and performed support work in various locations. Their voices have not yet been fully heard, probably because they left fewer letters and diaries. But, perhaps in time, their stories will yet be unearthed.

1. Dianne Dodd, “Canadian Nurse Deaths in the First World War,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, vol. 34, no. 2, 2017, pp. 327–363.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 7 January 2021