by Jenna Klassen

Winnipeg

|

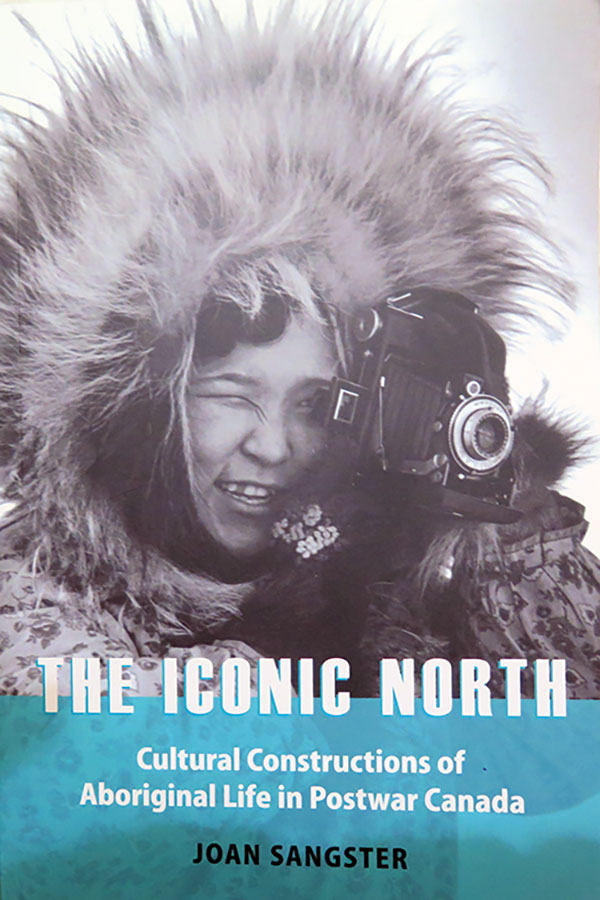

Joan Sangster, The Iconic North: Cultural Constructions of Aboriginal Life in Postwar Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016, 400 pages. ISBN 978-0-7748-3184-0, $34.95 (paperback)

For many Canadians, the North has become a distinguishing feature of the country, as both a place and an ideology. The landscape, flora and fauna, and the people who live there have captured, and continue to capture the interest of Canadians. Contributing to a vast scholarship focusing on this fascination, Joan Sangster explores the cultural representations of the North, and, particularly, representations of its Indigenous inhabitants in The Iconic North: Cultural Constructions of Aboriginal Life in Postwar Canada.

For many Canadians, the North has become a distinguishing feature of the country, as both a place and an ideology. The landscape, flora and fauna, and the people who live there have captured, and continue to capture the interest of Canadians. Contributing to a vast scholarship focusing on this fascination, Joan Sangster explores the cultural representations of the North, and, particularly, representations of its Indigenous inhabitants in The Iconic North: Cultural Constructions of Aboriginal Life in Postwar Canada.

After the Second World War, the Canadian state began to seek new opportunities for resource development and extraction. While the fur trade’s success was diminishing, the state saw other possibilities in Canada’s North. Portrayed as the country’s ‘last frontier’ for economic expansion, federal policies were created and development initiated. A connection between the North, its resources, and Indigenous peoples was symbolized by merging federal departments; by 1965, northern natural resource interests and Indigenous affairs shared the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. As Sangster demonstrates throughout the book, this connection between natural resources and Indigenous peoples was necessary for the state’s dual goals of economic development and the assimilation of northern Indigenous peoples into mainstream society as productive, modern Canadians. By constructing images of northern Indigenous life, Canadians in mainstream society were shown a way of life that was no longer viable, as the North developed and became modernized. Using a variety of sources produced by white Canadians, for white Canadians, Sangster argues that cultural representations of northern Indigenous communities in the postwar period were used as a method of promoting the assimilation of Indigenous peoples, nation-building, and ultimately the persistence of colonialism.

Sangster uses “gender colonialism” as a framework for the book, focusing on the role that gender played in the construction of these cultural images and their role in the perpetuation of colonialism. Other historians, such as Sarah Carter, have demonstrated these connections as well, particularly in the context of the settlement of the Canadian prairies in the 19th century. In the postwar North, images and stereotypes of Indigenous women as unfeminine, dependent on white paternalism, or even absent from the landscape, continued to permeate these cultural mediums. Sangster reveals contradictions, however, as images of Indigenous women adopting modern methods of living were necessary in demonstrating the positive aspects of northern economic development—assimilation. White women’s presence in the North symbolized the domestication of the last wild and rugged frontier of Canada’s sovereignty. Additionally, these women, through the material they produced, “played an active, constitutive role in the creation of colonial texts and ideologies” (p.68).

After her introduction, Sangster organizes her arguments by focusing on one form of cultural medium for each chapter. In the first chapter, she uses the travel writings of white women who spent time in the North. Sangster traces how these writings shifted away from a position of superiority to one that considered the perspective of the Indigenous groups they were in contact with, even while these women continued to hold paternalistic views of the Inuit and First Nations peoples living in the North.

The second chapter focuses on the writings and visual imagery of The Beaver magazine, a publication produced by the Hudson’s Bay Company. This magazine, popular among Canadians in the southern parts of the country, featured depictions of Indigenous life by “experts,” such as professional anthropologists and historians, and also amateurs of both fields. These articles written by “experts” documented the “disappearance” of traditional indigenous life through a nostalgic point of view, while promoting white settler progress in the North, and ultimately justifying the Hudson’s Bay Company’s colonial past and future.

In Chapters Three and Four, Sangster focuses on the role of film, through the television program “RCMP” and a variety of National Film Board (NFB) documentaries. Sangster’s study of “RCMP” episodes provides the space for an analysis of masculinity in the North. The white, male “heroes” of the series reflected a view of gender and race that was both colonial and masculine. Sangster demonstrates a relationship of mutual reinforcement between law, cultural production, and gendered colonialism that perpetuated mainstream Canadians’ views of Indigenous peoples. The NFB documentaries were produced to show the “truth” of Indigenous life in the North, while at the same time promoting assimilation and economic development. Again, Sangster reveals that these documentaries became more tolerant of Indigenous culture, though they maintained a tendency toward assimilative storylines.

The final two chapters return to the efforts of white women to understand northern Indigenous life. Irene Baird used historical fiction and non-fiction to document her interpretation of the northern experience, while researchers of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in the North (RCSW) were motivated by their desire to investigate the needs of Indigenous women that had for so long gone unaddressed. Sangster shows how, despite their good intentions, Irene Baird and members of the RCSW failed to truly capture Indigenous voices, appropriating or even silencing these voices throughout their work.

Throughout the book, Sangster successfully reveals how the perspectives of writers, filmmakers, photographers, and researchers were transformed as the postwar period went on. While traditional Indigenous culture and peoples were first presented through the perspective of white superiority, in the later part of the period a significant shift toward cultural relativism and tolerance (despite the persistence of portraying their culture as “artifacts of history”) can be observed. However, Sangster also expresses the limitations of white efforts, particularly in the case of the RCSW, where white female “experts” demonstrated “flawed expectations of universal womanhood” (p.228).

Sangster notes at the outset the absence of Indigenous voice and agency in the book. Although in the conclusion she describes three examples of Inuit cultural constructions of the North, this deficiency exposes a gap in Indigenous and Northern historiography. Additionally, examining white and Aboriginal responses to these examples of cultural imagery would be an interesting companion piece to this study (although there are a few scattered throughout, for example, ‘fan mail’ responses to Irene Baird’s stories).

The Iconic North is another thoroughly researched and beautifully written work by Sangster. While significant in length, the fascinating sources and rich detail of each chapter makes for an intriguing and enjoyable reading experience. Through cultural images Sangster shows how gender relations and race were significant in northern development, and reveals the persistence of colonialism in Canada’s postwar period.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 7 January 2021